Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

28 December, 2019

The Rotter brothers, Fritz and Alfred, were the most prominent private theater directors during the Weimar Republic before losing everything in 1933. There is hardly an operetta that premiered in Berlin that didn’t come out at one of their stages – Friederike, Land des Lächelns and Ball im Savoy are among the top titles. In 1933 their success story turns into tragedy, fatal escape and death. Swiss sociologist Peter Kamber will finally publish his well-researched biography of the Rotters in March 2020, after having searched for a publisher for years. Eventually Barrie Kosky, upon reading the manuscript, put his Komische Oper team on the task and connected Mr. Kamber with the publishing house Henschel. They will present the new book at the Leipzig book fair in a German language edition. On his homepage, Mr. Kamber gives an outline of the twisted story.

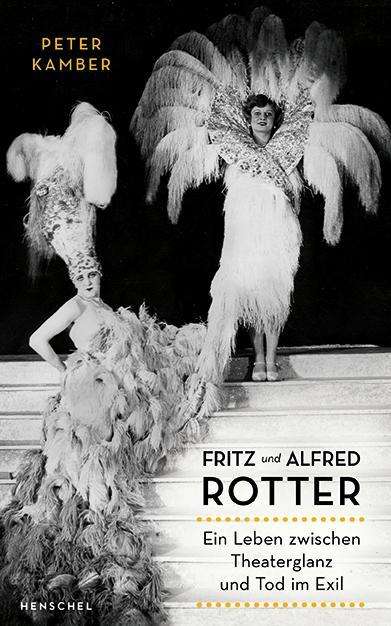

The cover for Peter Kamber’s “Fritz und Alfred Rotter: Ein Leben zwischen Theaterglanz und Tod im Exil.” (Photo: Henschel Publishing)

Born respectively on September 3, 1888 and November 14, 1886 in Leipzig, Fritz and Alfred Rotter were one and three years old when their parents moved to Berlin. Their shared passion for the stage began already in school and later they founded an academic theatre while studying law, staging plays by Strindberg up until World War I.

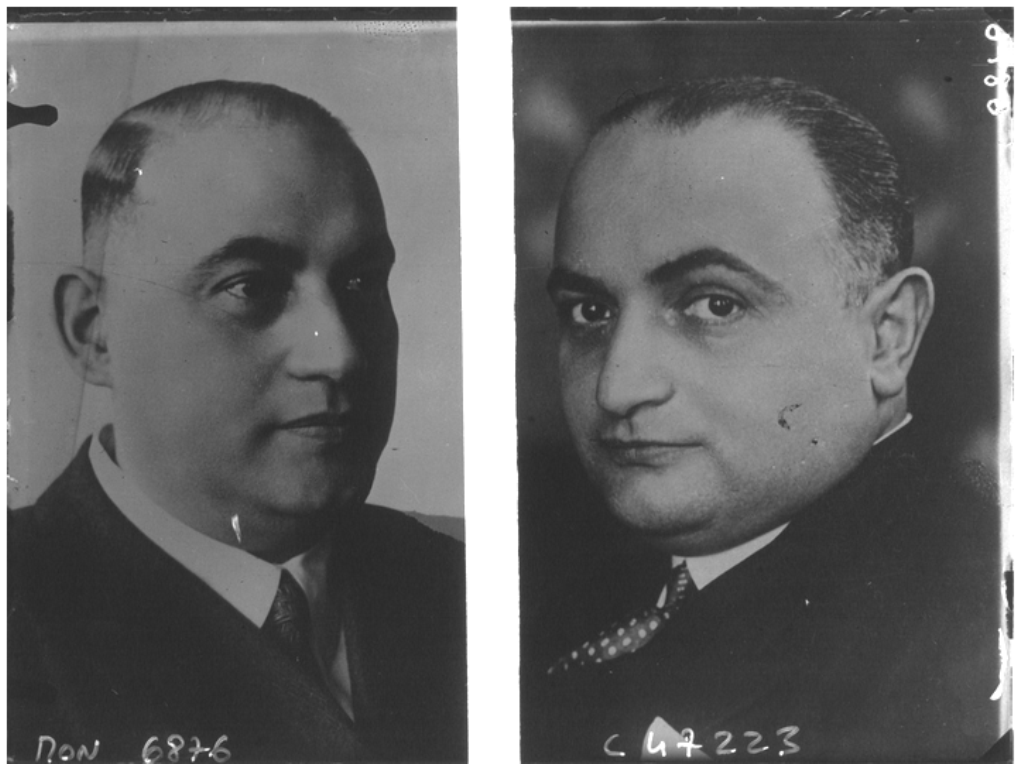

Alfred (l.) and Fritz Rotter in 1933. (Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France)

As small comedy impresarios they miraculously escaped being sent to the front by constantly changing addresses and were given their first theater concession during the November Revolution of1918. Both of these facts gave right wing nationalists cause to vilify and castigate the extremely popular and successful Rotter brothers for their provocative comedy style. In addition, since anti-Semitism was strong right after the war, the Rotters decided in 1924/25 to step back temporarily as producers and to lease or sublet their theaters for a while.

When they started up again in 1927/28, they switched to operetta and were even more successful than before. The New York Times concluded on December 8, 1929, “the Berlin operetta situation is in the hands of the Rotter brothers …”

Sheet music cover for Lehárs “Dein ist mein ganzes Herz” song.

With Franz Lehár as composer and Richard Tauber as singer they brought the genre of musical melodrama to the peak of perfection – first with Friederike (October 4,1928), and then with The Land of Smiles (October 10, 1929). Both were staged in Berlin at the Metropol-Theater, now known as the Komische Oper.

Referring to the elder Rotter Alfred The New York Times noted: “His belief is that the German public comes to the theater for a good cry, and the success of Friederike, in which the audience was given an opportunity to use up three handkerchiefs a seat, encouraged him in his conviction.”

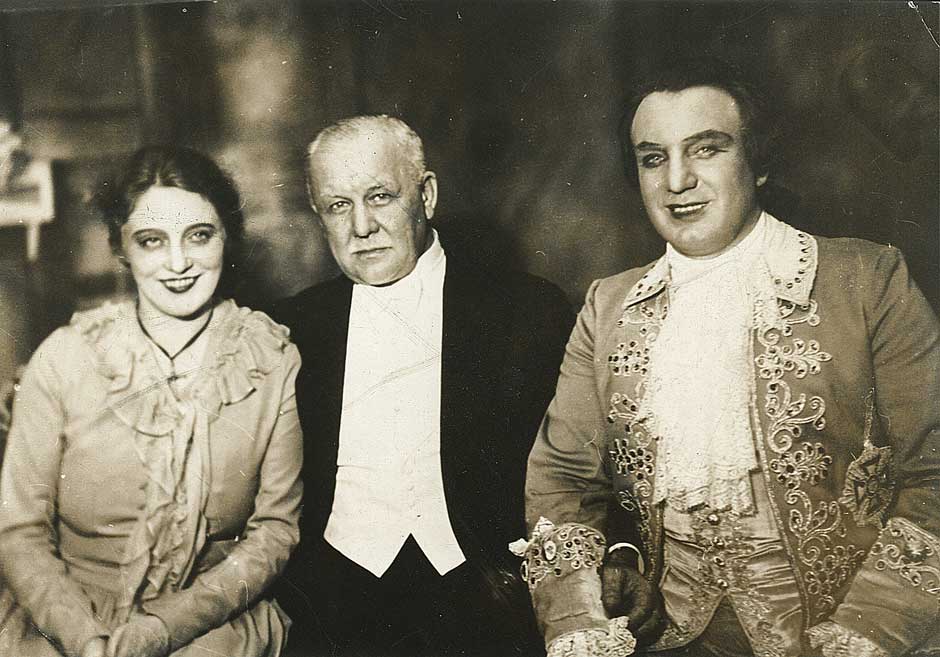

Franz Lehár with his two original stars, Käthe Dorsch and Richard Tauber.

In the meantime, they lost a lot of money at the stock exchange and banks stopped lending to them in 1931. Severely indebted, the Rotters seemed at first to have outwitted the world economic crisis with their consistent successes. But this was only possible because the ticket vending company, “Gesellschaft der Funkfreunde,” advanced them money for their new productions. Heinz Hentschke, the head of this company, who later became a member of the Nazi Party and Goebbels’ main man for operettas, started squeezing the Rotters even more in an effort to gain further control over them.

After their greatest success ever with Ball im Savoy, premiering on December 23, 1932, at Grosses Schauspielhaus with Paul Abraham as composer, Hentschke deprived Fritz and Alfred Rotter of all their due revenues for Ball im Savoy.

The London version of Abraham’s “Ball at the Savoy” with lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II, showing Rosy Barsony on the cover.

Refusing to declare bankruptcy, the Rotters left for Liechtenstein in January 1933 and never returned to Germany after Hitler took over. German and Liechtenstein Nazis tried to kidnap the brothers on April 5, 1933 in the mountains above Vaduz using gas pistols.

The Rotters fought back with walking sticks, managing to flee in panic from their attackers. Alfred Rotter and his wife Gertrud lost their lives falling down a rocky cliff hidden in the forest.

Meanwhile, the younger brother Fritz stepped unwittingly into the back seat of the car driven by a man feigning not to be one of the attackers and offering to bring him to the next house with a telephone. But when the driver accelerated instead of stopping where he should and was finally catching up with the escape car of the attackers, Fritz Rotter knew he had been tricked and threatened to strangle the man at the wheel. The careening car finally fell back, enabling Fritz to bolt from the car in a hairpin curve, thereby breaking his shoulder.

A so called “Stolperstein” for Fritz Rotter in front of his villa in Berlin-Grunewald, commemorating his fate. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Afterwards he found exile in France until he landed in a prison in Colmar for passing on a bad check. There he died for unknown reasons on October 7, 1939.

This epic story would surely deserve a film treatment, it most certainly deserves an English translation. For the tale of Heinz Hentschke, check out Matthias Kauffmann’s book on in the Third Reich.

Fascinated to read this. My grandmother, Anneliese Guthmann, worked for the Rotters after her husband, Hermann (who also worked for them) died in 1924. She lost her job c 1932, which I assume was linked to the bankruptcy. My grandmother was, I believe, involved in travelling to the various theatres in connection with paying the artistes. She got to know Lehar and Tauber (and the latter may have had a bit of a fling with my grandmother, who was a very glamorous young woman)..