Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

22 September, 2018

It’s not exactly a secret that Johann Strauss was a great dance music composer. Before he turned to operetta in 1871 with Indigo und die 40 Räuber he had made a name for himself with some of the most immortal waltzes ever written, and he would continue writing them, also for his various operettas. But it was not just music in ¾ time that’s his claim-to-fame, he also wrote superb polkas, marches, and whatever else people wanted to dance to at the time. Even though Strauss turned to stage works, which promised higher royalties as Offenbach had proven, he never composed a ‘pure’ dance show, i.e. a ballet. Until 1898 that is. In March of that year the newspaper Die Waage asked readers to submit an idea for a ballet for Strauss that was to premiere at the Court Opera in Vienna, then under the artistic direction of Gustav Mahler, on the night of the opera ball. This ball was first called Hofopern-Soirée and took place in December, it was then renamed ‘Redoute im k. k. Hof-Operntheater’ and happened two to three times a year; the ladies remained masked until midnight. Mahler promised the new ballet a series of performances after the ball. So, potentially, the person whose idea and script would win the 1st prize could make a lot of money.

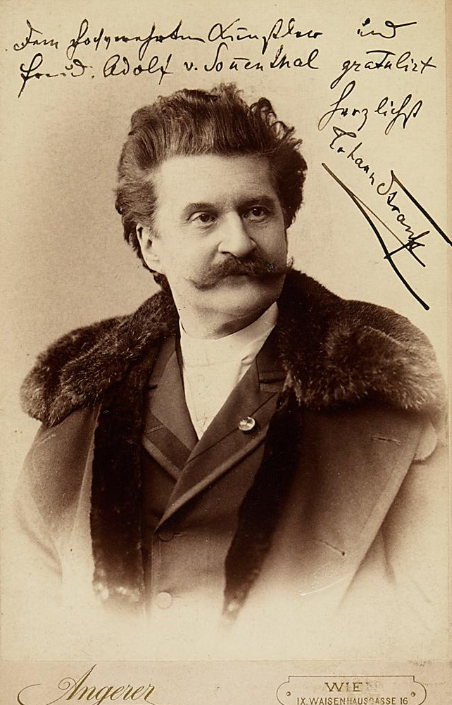

A late portrait of Johann Strauss, with his signature. (Photo: Victor Angerer / Theatermuseum Wien)

718 scripts were sent in, clear proof that many people wanted to win the illustrious jackpot. The jury that had to select a script was not too enthusiastic about what they got to read: mostly fairy tales and fantasy stories such as Peter Schlemihl or Rübezahl (a still popular German language fairy tale). The initiator of the newspaper competition, journalist Rudolf Lothar, eventually settled for Aschenbrödel, which is the German name for Cinderella. Since Strauss insisted on a ‘contemporary story’ the Cinderella saga had been updated by ‘A. Kollmann’ (a pseudonym behind which the journalist Karl Colbert hid) and re-located to a fashion salon on the day of the Viennese Hofopernball, i.e. the opera ball, act 2 takes place at the ball itself, act 3 moves back to the salon.

In this rom-com version Cinderella is a shop assistant called Grete, terrorized by her step mother, Mme. Françine, and her daughters Yvette and Fanchon, they all work in the salon too. They are all after a painter called Leon, who they hope to meet at the masked ball. When Grete meets Leon there he loses his heart and she her shoe. You can probably imagine the rest. (Yes, he comes into the fashion salon in act 3 with the shoe.) You can read the full Kollmann/Colbert script online at the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, it was rediscovered not too long ago by Strauss researcher Ralph Braun.

The story of the ‘good’ Austrian girl called Grete outshining the ‘evil’ French girls Yvette and Fanchon was very much in sync with the nationalistic and anti-French attitudes that dominated Vienna in those years and that had caused a shift in operetta production, too, away from the ‘scandalous’ French Offenbach model and towards a more morally ‘suitable’ home-grown model exemplified by Millöcker and his new kind of heroic operetta tales. With ‘serious’ music, of course. Strauss’s later works were also seen as a ‘serious’ answer to the unheard-of frivolity of ‘that (Jewish) foreigner’ Offenbach. The anti-semitism at play here was pretty staggering. It still is. (Given these circumstances it’s not surprising that Mr. Colbert used the pseudonym Kollmann for this Strauss ballet project.)

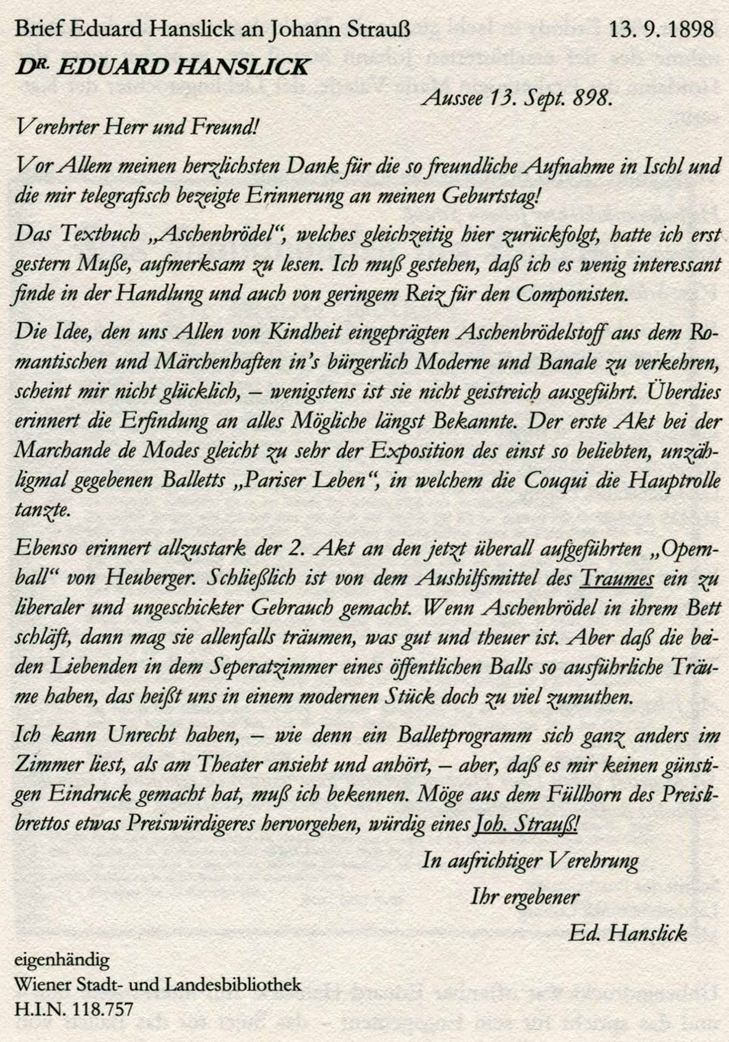

Kollmann’s Aschenbrödel story was not appreciated by everyone, the influential music critic Eduard Hanslick, a close friend of Strauss, disliked it. He wrote in a letter dating 13 September 1898 that he considered the fashion salon setting too closely linked to Offenbach’s La Vie Parisienne, which had been turned into a successful ballet, and the opera ball setting of act 2 reminded him too much of Heuberger’s Opernball which had premiered in January 1898.

Letter by Eduard Hanslick to Johann Strauss, 13 September 1898. (Copy from the complete edited letters edition of Johann Strauss.)

This might explain why Strauss was furious when he himself finally saw Heuberger’s Opernball and wrote an outraged letter to his brother-in-law Josef Simon, in typical Strauss style known from many other letters: “Die Schwanzhaare soll man ihm, wenn er welche hat, ausreißen u. ihm in einer Sardellensauce zu fressen geben damit er lebenslänglich 10 mal des Tages scheißen muß u. z. mit obligaten Bauchkrämpfen und Speiberei.“ If you need an English translation, here it is: “Someone should tear his pubic hairs out, if he has any, and he should be given anchovies sauce to eat so that he has to shit 10 times a day for the rest of his life, not to mention that this will hopefully give him stomach cramps and cause him to throw up.”

The Vienna Court Opera in 1898, when Gustav Mahler was artistic director.

Still, Strauss went on setting the little loved script to music. In February 1899 he told a newspaper that he was busy composing and had nearly finished the score, expecting the world premiere of Aschenbrödel in November at the Court Opera in Vienna. But he died in June 1899, and left the project unfinished.

His widow Adele looked for someone to complete the job and turned to Josef Bayer who had been conducting ballets at the Court Opera for 13 years and had also composed various ballets himself, among them the successful Puppenfee.

Piano score cover for Josef Bayer’s “Puppen” ballet (The Fairy Doll).

In December 1899 Bayer presented a complete piano score with all the cues from the Kollmann/Colbert script. Bayer also prepared a full orchestra score using Strauss’s finished pages and had the ballet ready for production for the opera ball. In the meantime, however, Gustav Mahler had pulled out of the project that he never much liked anyway. He claimed that with Strauss dead he wasn’t going to present a Strauss ballet on this festive occasion, or any other occasion.

The Theater an der Wien, where so many Strauss operettas had premiered, also said no. So Adele Strauss and Mr. Bayer turned to Berlin’s Royal Opera House. They were interested, but the ballet director there, Emil Graeb, didn’t like the script too much and insisted on re-writes which were undertaken by Viennese author Heinrich Regel. In the new version, the story is set in a big department store, in the fashion department. And Leon is not a painter anymore, but instead the wealthy owner of the store named Gustav. Act 2 doesn’t take place at the opera ball, but at a private party à la Fledermaus given by Leon. Again, Grete and Gustav fall in love there, lose hearts and shoes, and in act three find each other.

Changing the story slightly around meant that the music also had to be changed around: Mr. Bayer cut up his score into 95 parts which he re-arranged to fit the new plot, he also shortened the score. In this version the ballet premiered on 2 May 1901 in Berlin. According to newspaper reports it was a success, but it did not travel internationally: only 3 performances in Königsberg are recorded, and one (!) in Insterburg, wherever that is. Adele Strauss and Josef Bayer were not blessed with royalties as a result.

Felix von Weingartner around 1914. (Photo: Nicola Perscheid)

In 1908 Felix von Weingartner replaced Mahler as director of the Vienna Court Opera, and Weingartner was an outspoken advocate of Strauss’s music, unlike Gustav Mahler who did not favor ballet or dance music particularly. One of the first things Weingartner did when he became director in Vienna was put Aschenbrödel on: it premiered in Vienna on 4 October 1908, but again not in the ‘original’ version, but in the Berlin big-department-store-edition.

Even with the name Strauss attached to it, and even with an evergreen topic such as Cinderella, the ballet didn’t have a noticeable career after that. Richard Bonynge resurrected the score decades later in another new version, edited by Douglas Gamley. It was released by Decca as a double disc, and it’s great fun to listen to. Even if the story of Grete and the whole aspect of a modern-day fairy tale is completely irrelevant to this recording. It’s simply a collection of boisterous Strauss tunes, in a typical 1980s ‘enhanced’ orchestration, the same kind of ‘enhancement’ you know from the Sutherland/Bonynge operetta recordings. They are a document of their times and tastes, and like times tastes change.

Then, in 1999, there was a production at the Vienna State Opera created by Italian dancer and choreographer Renato Zanella. It was conducted by Michael Halász and had costumes by Christian Lacroix: including a partly topless Prince/Leon, and a lot of gold and glitter elsewhere. It was later released on DVD, and it’s also based on Heinrich Regel’s Berlin re-arragement of the story, plus some extra music to spice up the score with ‘hits.’

Fast forward, and you now get this new double disc on cpo conducted by Ernst Theis, recorded in Vienna in 2014 and released in 2018. It’s based on the 2002 version of the Neue Johann Strauss Gesamtausgabe, edited my Prof. Michael Rot. On the cover of the CD it says ‘Complete Ballet,’ in the booklet Prof. Michael Rot explains that this is supposedly the ‘first recording to present the reconstructed original version’ of Aschenbrödel. And, needless to say, Prof. Rot hopes that it will now finally make the international rounds … so he gets his royalties, unlike Adele Strauss and Josef Bayer back in the day.

The 2014 recording of “Aschenbrödel,” released on CD in 2018 by cpo.

In his CD essay Prof. Rot states that he started working on Strauss’s ‘only independent ballet composition’ in the 1990s, the material for Aschenbrödel being stored at the Wienbibliothek. According to their catalogue there were supposed to be 480 pages of music – but as it turned out these pages were ‘lost.’ Which is a euphemism, because they were actually stolen and sold by the former director of the Wienbibliothek. (Original Strauss hand-written pages are big money.) The Wienbibliothek tried to hush the scandal up, until the German police stepped in when material was offered to Ralph Braun in Coburg in 2010. (Read more about it here.) As a Strauss expert Mr. Braun recognized what the pages were and contacted the authorities, after the Viennese authorities had refused to act. (He had also contacted them.) So, eventually, much of the material was returned, but Prof. Rot actually recreated the ‘original’ Aschenbrödel long before that. He also claimed, back in 2002 when his edition came out, that the original Kollmann/Colbert script didn’t exist, only in a copied version within the Bayer piano score. Well, he might want to take a second and third look now! (Again, it was Ralph Braun who found this material which is meanwhile available online.)

In the Neue Johann Strauss Gesamtausgabe Prof. Rot says that in the surviving pages – not ‘lost’ – there is only one page that’s in Strauss’s own hand writing: we’re talking of four bars of music. From these four (!) original Strauss bars Prof. Rot constructed a 504 page ‘sorce critical score’? (Read more about this here, page 22 onwards.) You might find this a little puzzling.

Fascimile of the “Aschenbrödel” Strauss’s score in handwriting, shown in 1911 in Erich W. Engel’s calendar „Johann Strauss und seine Zeit“. The calender states that this pages was in the possession of Mrs. Strauss. (It was later confiscated by the Nazis.)

Obviously, there are quite a few fake news in circulation here, most importantly this: there is no full ‘original’ Strauss composition. What there is, is the original Josef Bayer piano score and the various orchestra parts based on Strauss’s own orchestrations. So, what you get, in effect, is a recording of Bayer’s Aschenbrödel as it should have premiered at the Vienna Court Opera ball in 1899. Which is interesting, obviously.

Conductor and composer Josef Bayer around 1900.

If you’re not a died-hard Strauss fan, in search of the last composition by Strauss, you might take this Aschenbrödel simply as a collection of charming melodies. There is no real drama or dramatic build-up, so (to my ears) it’s more or less irrelevant whether you’re hearing the Viennese or Berlin order of musical numbers; and the re-instated numbers that had been cut for the Berlin production are not so breathtaking as to make this cpo Aschenbrödel a must-have. Certainly not if you already own the Bonynge version which outshines Mr. Theis’s conducting in pure exuberance and glossy appeal.

Theis and the ORF Radio-Symphonieorchester take Strauss very seriously, to the point of sounding a bit dull. The music rarely lifts you off your seat, so I doubt whether this cpo double disc is the best possible advocate to put Aschenbrödel in the Rot/Bayer version on its belated road to fame and fortune.

As Ralph Braun has pointed out elsewhere, there’s nothing wrong with presenting the 1899 original Viennese version of Aschenbrödel on disc (even if Eduard Hanslick and others had great reservations about the plot), but no one should claim it’s a reconstructed Strauss score. There’s still a lot of hush-up about the ‘lost’ pages, and a lot of lies to not put a spotlight on the scandal at Wienbibliothek. Prof. Rot doesn’t seem to want to tell what exactly he knew back in the 1990s and how this affected his reconstruction, which was obviously not based on only four bars of original hand-written Strauss music. (Or was it?)

For a real re-evaluation of Aschenbrödel as a stage-work and contribution to ballet history it would be necessary to actually see a staging: fashion salon, modern-day costuming and sets included. It’s questionable whether Strauss’s Cinderella can ever replace such favorites as Prokofiev’s 1945 neo-classical Cinderella. Not to mention Disney.

If that’s your competition, you need a bit more than Ernst Theis and the solid ORF forces, and you need a better packaging of your product than this.(Why, for God’s sake, is there a paper cut on the cover that suggests a 18th century setting when the ‘original’ story is set in a modern-day, i.e. 1900, fashion salon/department store? Did the art director at cpo not get a briefing from Prof. Rot and the editors of the booklet?)

By comparison, other late Strauss works completed by someone else have fared better, if you think of the ever-popular Wiener Blut which premiered at Vienna’s Carltheater in October 1899, around the same time Aschenbrödel was supposed to have premiered, too. Wiener Blut had the sensational sensual eclectic dancer Louis Treumann as Josef. I’d love to see a production of Aschenbrödel that incorporates such sensuality and eccentricity, giving the ballet a real new chance, a chance that the 2016 production at Landestheater Coburg didn’t grab by the balls either. (Watch a trailer here.)

Coburg’s ballet director discarded the idea of the department store and fashion element, his Leon/Gustav was just a plain Prince Charming with punk hair and exposed nude chest. (Again?) And the rest was fairy-tale-as-usual. I believe Strauss deserves better than business-as-usual, and that includes Aschenbrödel.

There is so much background information and so much strange stuff going on regarding this edition of the Neue Johann Strauss Gesamtausgabe that this might explain why the Theis recording didn’t take place until 2014 and why the CD release, again, took another four years. Maybe someone will make a wonderful TV documentary about all of this … and give Aschenbrödel new life that way?

I found this CPO release charming. I also own the 1980 London release of Aschenbrodel. Each recordings have their merits. The late Joseph Bayer did a fine job in completing the score of Johann Strauss. Only Strauss alone could have done his magic for his only Ballet. One of those great what if Strauss had not died before finishing the full orchestral scoring. Would the Ballet be a world wide success?? We will never know. Yet, we do have the Ballet as is that just needs a perfect staging of performance and inspired conducting of the music to bring it alive. As a true fan of the Waltz King. Iam pleased that I own two CD versions of Aschenbrodel to listen too. Plus the Vienna State Opera production of 1999 to honor the centennial of Johann Strauss II passing on DVD.

Where is it claimed that Bonynge’s recording is in a “…1980′s enhanced’ orchestration”? The orchestration in Bonynge’s recording is no different than any other opus by Strauss II or his contemporaries in the annals of “light music” in the Viennese style. I have no doubt that if people were not aware of Bayer’s contribution they would have a far more positive opinion of the score. Should Strauss had finished the score, I doubt very much that it would have been drastically different from what Bayer did with whatever material was completed before Strauss’s death. Regarding the recent Theis/ORF recording of Aschenbrödel, it is interesting to hear the “complete” music, but the arrangement used is run-of-the-mill (making me suspect that there are missing elements in the orchestration) and the performance does nothing to compensate for this and is dull as hell.