Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

7 October, 2017

In 2016, The Black Crook celebrates its 150th anniversary, marking 150 years of the American Musical. To commemorate the sesquicentennial, Joshua William Gelb brought back his 2007 play about the creation of the original The Black Crook, then seen at the Abrons Arts Center on the Lower East Side and now playing there again, to critical acclaim as well as to some controversy. We spoke with Mr. Gelb after attending a performance in September to find out more about his personal fascination with The Black Crook and to ask where he got all that information from which he uses so brilliantly in his play.

Playwright Joshua William Gelb. (Photo: Josh Luxenberg)

You have written a very detailed – and historically rich – play about the creation of the original Black Crook in 1866. That must have required extensive research. Where did you find your background stories on Charles M. Barras, Niblo’s Garden, producer William Wheatley etc.?

For a long time the only published version of The Black Crook was in an anthology of 19th Century American Plays, in which Myron Matlaw writes a compelling abbreviated history of the production. Once that had sparked my interest, I mostly relied on the writings of Niblo’s Garden treasurer, Joseph Whitton, who wrote an 1897 backstage “tell-all” about the making of the original 1866 production called The Naked Truth. Unfortunately, I’ve found Whitton to be a somewhat unreliable narrator. He leaves out major elements of the story, including the burning of the Academy of Music (which stranded the Parisian ballet troupe that would eventually be integrated into The Black Crook), and actually may have quit his position well before opening night. All of which goes to say that most of the contemporary writings about the Black Crook, whether Whitton’s book or the hundreds of newspaper articles written on the subject, are less than authoritative. I also worked through some 20th century scholarship on the piece from the likes of Julian Mates, Leonard Bernstein, among others, but so much of the modern musings on The Black Crook devolve into arguments as to whether or not it was indeed the first musical. This has always been an issue of semantics for me. I’m more interested in interrogating the mythology of this origin story; what does The Black Crook as the so-called first musical say about America today?

Scene from the 2016 production of “The Black Crook.” (Photo: Kelly Stuart)

At the end of your play, you list all the productions of The Black Crook that played till well into the 20th century. Why do you think audiences wanted to see it again and again until the 1920s? And what changed then, for the show to disappear from the stage?

Following the Civil War, the Gilded Age was a ruthlessly capitalistic period in the Northern States of America, and as a commercial commodity The Black Crook wasn’t broken… so why fix it? The Crook succeeded precisely because it was born at the apex of several technological developments that began what we would consider mass media today. The transcontinental railroad, the transatlantic cable, the camera; these technologies made it possible for The Black Crook to become a national, indeed international, sensation. But unlike today, you still couldn’t record sound or video, so revivals needed to keep popping up in order to satisfy the demand. But the popularity of The Black Crook was always ridiculed in more cultured circles, so I don’t think it’s surprising that by the end of its three decade reign in New York City alone, the Black Crook had become a parody of its already parodied self. And I don’t think it’s wrong to imply that the artistic stagnation epitomized by decades of ever more decadent, melodramatic Black Crook revivals is among the factors that lead to the emergence of what’s now classified as modern American Drama as well as the modern book musical.

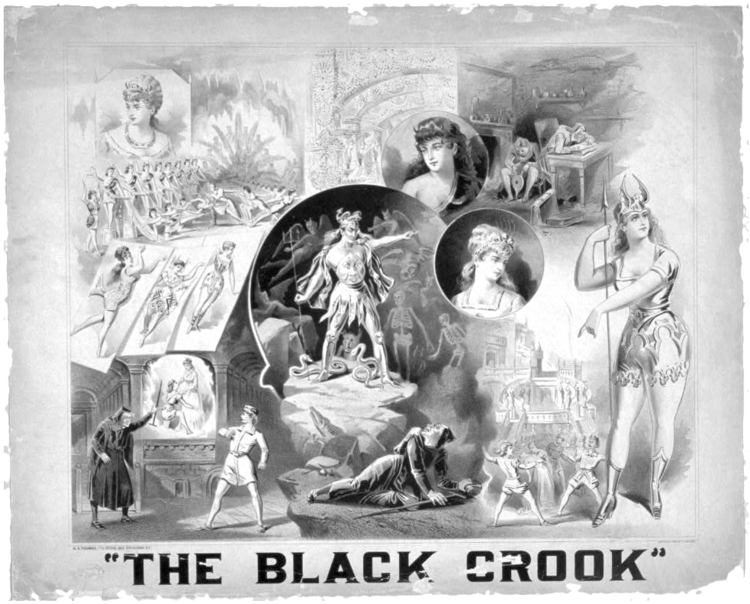

Poster for the original “Black Crook” production showing various scenes from the play.

Considering all these productions around the country and in New York itself, what’s the situation on performance material: could anyone today grab a full set of orchestral parts and a script and play the “original” Black Crook in any of the historical versions?

I supposed it’s a little more complicated than that. Certainly the script is available on-line, but not the score in full. Our production spent a lot of time digging up old programs and prompt books in order to reconstruct a version of what the score might have been, so while our production includes some songs from the original, it also relies on some from subsequent revivals, and some from the same period that merely fit the mold of what we believe might have been heard.

But truly, the score of the “Black Crook” was so fluid and interchangeable, with songs frequently being changed-out through the run, that it’s hard to really pin down a supposedly authentic version of the score, if you could really call it a score at all.

Famous shows such as Show Boat (1927) have been recorded in their reconstructed original versions. Why has there not been a modern day recording of an important show like The Black Crook? Would such a recording of the mix of songs be of any interest to modern-day Broadway aficionados?

Without a doubt. And indeed the Music Director Adam Roberts and group of singers from Austin, Texas have recorded as many of the songs as they could uncover, which you can listen to here. But again, the notion of an original score is such a moving target, that any authoritative, reconstructed version is still heavily theoretical. Moreover, I have to admit I’m not exactly a huge fan of that old style of mid-19th century music. Though it has been really satisfying working with my arrangers, Alaina Ferris and Justin Levine, to uncover a beautiful musicality in what I had originally dismissed as being “bad music.”

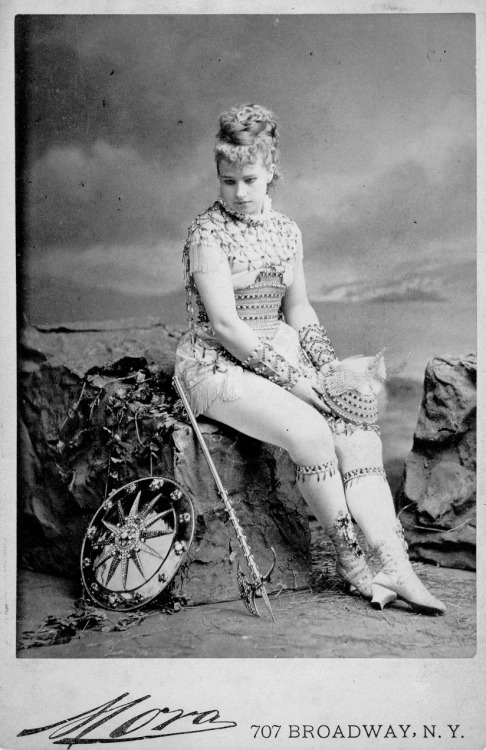

Singer and burlesque dancer Pauline Markham as Stalacta, Fairy Queen of the Golden Realm, in “The Black Crook.”

There are many compilations of early vaudeville material, early Broadway songs, early anything. Has anyone ever put together historical recordings of the Black Crook hits? (What are the big hit numbers, how would you describe them, what is particular about them, what is still interesting about them?)

The biggest hit at the time was “You Naughty, Naughty Men” by Theodore Kennick and G. Bickwell, which has gone down in lore as being one of the first major American pop-songs. It’s a vaguely titillating comic number along the lines of the more famous Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay, which you can find recorded in a couple places especially in brass band arrangements. Funny enough, however, the song wasn’t American at all, nor did it originate in The Black Crook. It was an old speciality act for Milly Cavendish, the English actress who was brought to the States to play the role of Carline in the original production. This is the one song from The Crook that Leonard Bernstein addresses in his 1956 Omnibus lecture on the origins of Musical Comedy, which I imagine is the only reason anyone is vaguely aware of it today.

In your play, you let the actors perform scenes from the “original” Black Crook in a very grand and stylized fashion that is unfamiliar to most modern theater goers. How would you describe that 1866 style of performance? What are the benefits (or drawbacks) of such a stylization? Why would it appeal to audiences of 2016? What could we, possibly, learn from it?

Throughout the rehearsal process we followed an extremely systematized performance technique set down in the 18th and 19th centuries that literalized the emotion of a scene through physical gesture. This was before realism, before psychology, before recorded sound. So all of our 20th century conceptions of how to act on a stage basically went out the window. To recreate this style we worked with various sources including the writings of oratory specialist Francois Delsarte. We also worked off of old silent films, which are really incredible resources for seeing old gestural performance in action. Murnau’s Faust and Robert Wiene’s Der Rosenkavalier were particularly instructive.

As for the bombast of delivery I think it’s important to remember that these texts were always intended for enormous unamplified theaters. Certainly when this style is performed to a house of 70 the artifice is somehow magnified, but I find that tension quite interesting. Actually, I’m of the opinion, that this broad, gestural style is still quite evident in the choreography of most contemporary musical theater.

Niblo’s Garden in New York, at the corner of Prince Street and Broadway. It was demolished in 1895.

The Black Crook, as it was eventually produced at Niblo’s Garden, was a gigantic mish mash of Bellini, Der Freischütz, farce, ballet etc. Isn’t such a mix-up rather modern, and typical of our re-sampling age? Does a rediscovery of that aspect bring The Black Crook closer to our era?

Absolutely, and I think that mash-up sensibility is a large part of its success. The Black Crook was at once a melodrama, a ballet, a vaudeville, and a peep show. It had something for everyone and was shameless in its introduction of surprising new elements. Since Rogers and Hammerstein, musical theater writing has become extremely concerned with trying to find formulas or at least some sense of internal logic for how music should interact with a particular narrative. The Black Crook didn’t care about this sort of dramaturgical consistency whatsoever. In fact, William Wheatley, the original producer, called the script little more than “a clothesline on which to hang expensive costumes, dances, and scenic designs.”

Scene from the 2016 production of “The Black Crook.” (Photo: Kelly Stuart)

Interestingly, the story of Rodolfo and Amina (names straight from La Sonambula) is set in Germany, in the Harz Mountains. Isn’t that a somewhat surprising setting for the so called “first real American musical”? Why Germany and not some US locale?

I think it only demonstrates the degree to which the plot of The Black Crook was pilfered from mostly Germanic sources. Bernstein derided The Black Crook for this flagrant Euro-centrism, but I also think that it was a major selling point for the production. A German story. British Performers. A Parisian Ballet. Though I guess I would agree that this cultural amalgamation is distinctly American.

You let the actors perform a few of the original songs in your play. Is it music that needs to be sung beautifully, or acted with real character to make an impression? (Is The Black Cook score music that demands opera voices, or wild vaudeville performers? How did your 2016 cast react to the musical numbers and its style/performance requirements?)

The Crook is a grab bag of vocal styles, from operatic ballads to vaudeville novelty numbers, and they are extremely typical of the time period. One of my favorite songs in the show is called “Dare I Tell?” which is a comic pastiche of operatic love songs, with intricate vocal runs that grow progressively longer until the singer can barely breathe. What makes the song so difficult is it demands operatic chops from comic performers, and I think that’s what’s so satisfying about the production musically; that it can be broad and brassy and ridiculous, while also musically meticulous, lush, and even sentimental. In the original production this was merely a way of accommodating crowds of differing cultural taste.

In our incarnation, producing this variety of style is more a matter or virtuosity.

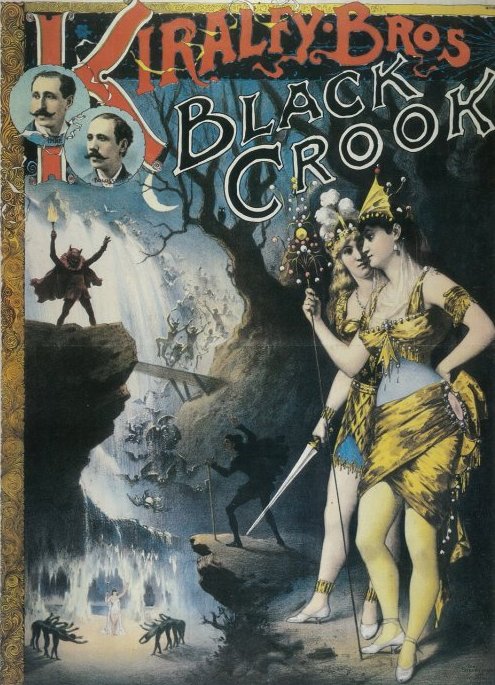

Poster for the “Black Crook” production 1866.

One of the big “selling points” of the show, back in 1866, were the half nude ballet girls from Paris “wearing no clothes to speak of.” Obviously, sex and nudity sold. Why has this central aspect been so overlooked in the books on Broadway history (and success) in the decades that followed, because obviously the producers at Niblo’s Garden were very ahead of their time. There hasn’t been a Broadway show with real nude girls of any shock value since. Or has there?

I think Broadway Producers have always been willing to market sex to the extent that it is both provocative and commercially appealing. The chorus girls in The Ziegfeld Follies come to mind, as well Gypsy, Fosse, and even literal nudity in countercultural shows like Hair, or Rocky Horror, or Oh! Calcutta! Actually, before The Black Crook was known as the first musical it was considered the first “leg show.” And while it may be difficult to imagine the scandalized uproar when looking back at the extreme modesty of those original costumes, the reaction at the time was genuinely extreme. The New York Herald likened Niblo’s Garden to Sodom and Gomorrah. Charles Dickens was absolutely appalled. And Mark Twain couldn’t help but describe the show as being “nothing but a wilderness of girls.”

My favorite review of “The Crook” calls it, “a sensualist’s fantasy” and I think the original producers were absolutely brilliant to seize upon the conservativeness of the time with an air of such gratuitous abandon.

You have re-cast your play for the 2016 production. Who are your actors, and what is special about them, if you compare them to a typical Encores! revival project?

It’s always been my goal to assemble a group of quadruple threats for this project. All in all, there are 8 performers, each playing at least 2 roles and collectively playing piano, bass, violin, banjo, accordion, harp, and percussion. So while we don’t have the ability to depict the opulent scenic spectacle of the original production, there’s a sort of spectacle of talent on display. Some of the performers, like Kate Weber and Randy Blair, who play the comic duo Barbara and Puffengruntz, have been with the show for nearly 10 years. Others, like veteran character actor Steven Rattazzi, who plays the dual role of the hero Rodolphe and the beleaguered Black Crook playwright Charles M. Barras, are entirely new to the project. Alaina Ferris, who co-arranged the music is pulling triple duty as music director and performer.

Scene from “The Black Crook” 2016. (Photo: Kelly Stuart)

Watching your play made me wonder if there will be a film version anytime soon, because your script would make for a great movie. Have you spoken with Hollywood of HBO yet?

If you have a connection to HBO, I’d be happy to sit down for a meeting, but as of now there are no actual plans to film the adaptation. Though I agree that it would be a fascinating project, especially since a film could truly capture the absurd scale of the original production in a way that economics of theater-making today could not.

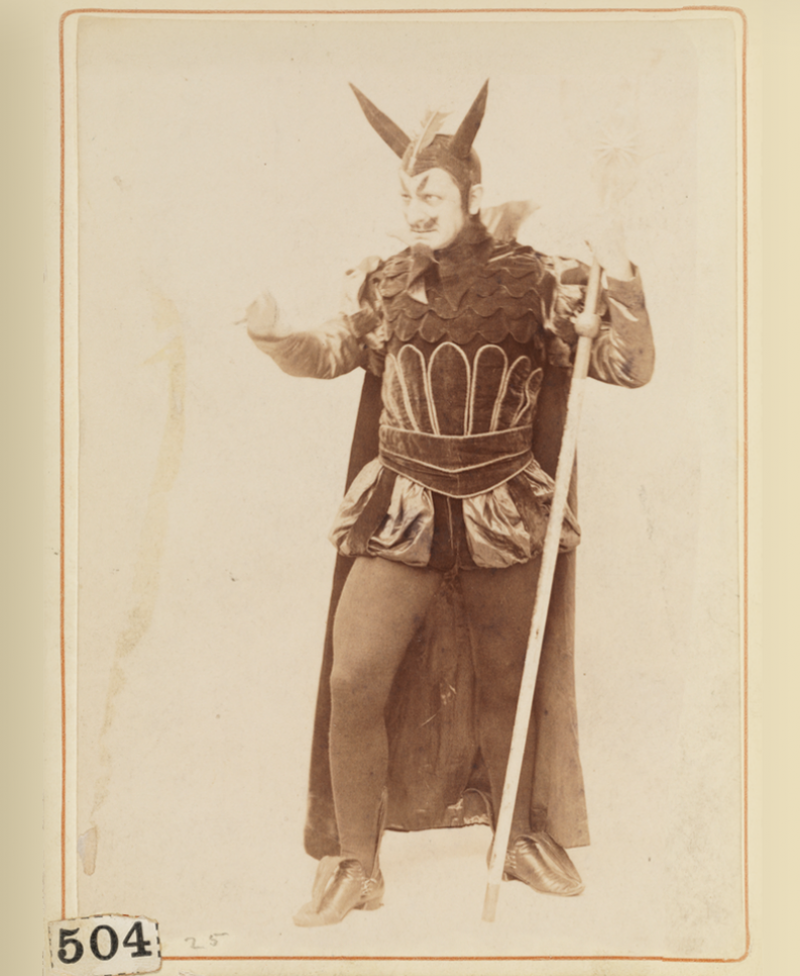

The devil in the original 1866 production of “The Black Crook.”

Some people complained that you announced your show in a wrong way: it was advertised as “The Black Crook: An Original, Magical and Spectacular Musical Drama” and “a team of only eight actor / musician / dancers will perform the full 1866 musical and bring the biggest of all American spectacles into the tiniest of spaces.” Can you understand the criticism? Would you re-label your production today?

Well, we perform the script of The Black Crook virtually in its entirety, so while I understand the criticism, I think we do exactly what was promised. A full recreation of The Black Crook would be a financial catastrophe, and artistically rather unsatisfying, I think. Which is why I’ve always considered an examination of The Black Crook’s importance as an American theatrical relic as the more interesting approach to the material.

Is your Black Crook going to be seen anywhere else? Will it tour the USA, like the original Black Crook did?

Currently, this is the final resting spot for The Black Crook. I’m just glad I got to put it up in time for the 150th anniversary.

What got you hooked, originally, on this show and its history? Are there any other historical shows that had a similar effect on you and your creativity?

I’ve always been fascinated by the motley production history of Bernstein’s Candide, and its ever changing libretto. We’ll see if I ever get a chance to tackle one of its many incarnations, or perhaps all of them.

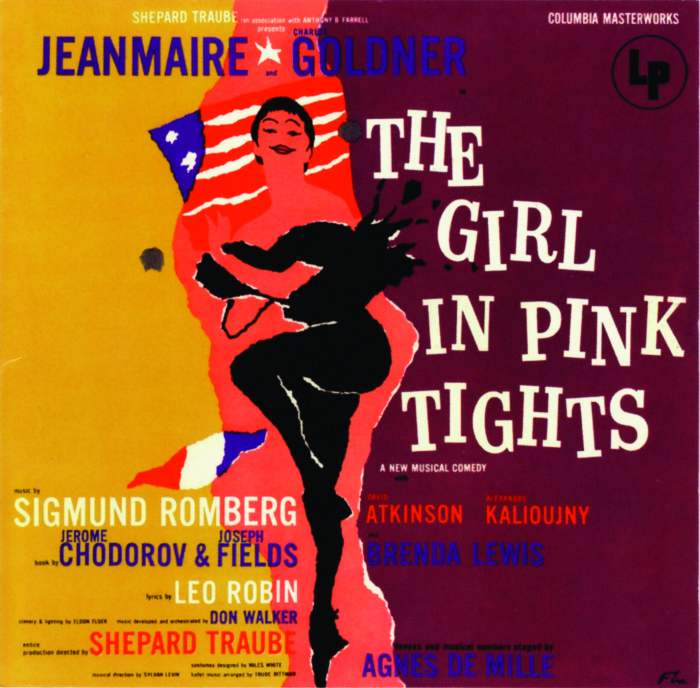

LP cover of “The Girl in Pink Tights.”

In 1954, the Romberg show The Girl in Pink Tights opened on Broadway. It’s also about The Black Crook. Is that a show of any interest to you?

Oh yes! I’ve listened to it many times. But it has little relation to the actual history of the original production (aside from the fire at the Academy of Music and the resulting abandoned Ballet Corp). Delightful music though. And I love that it was choreographed by Agnes De Mille, who has her own connection to Black Crook lore. She choreographed one of the last major Black Crook revivals in 1929, which was directed by Christopher Morley at the Lyric Theater in Hoboken in a similar effort to exhume Barras’ original play.

Would the “real” Black Crook be worth reviving today? If yes, where would you want to see it done, and with whom?

I honestly don’t think it’s worth the effort. A production on the scale of the original, which was the most expensive show of its time, would have to surpass Spiderman: Turn of the Dark at 75 million. 100 performers. A full orchestra. A stage with a built in elevator that lifts entire scenes, the likes of which only exists in New York at the Metropolitan Opera and Radio City.

The potency of “The Black Crook” was in its sheer excess, not its artistry, so a faithful recreation will always fall short, because nothing can truly capture how spectacular it was at that particular point in American history. I would much rather see a cinematic reproduction.

What’s your next project?

Right now I’m about to release a live-concert album of my latest musical, which was written with composer/lyricist Stephanie Johnstone and is called Hail Oblivion: A Musical Fantasia on Piratical Themes.

Advertisement for the 1916 silent movie version of “The Black Crook.”

Absolutely wonderful article/interview. Thank so much Kevin!