Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

19 December, 2022

The 1926 Kálmán hit Die Zirkusprinzessin – with a libretto by Julius Brammer and Alfred Grünwald and the memorable song “Zwei Märchenaugen” – is currently back on stage at the opera houses in Coburg and Hannover in Germany, as a sort of Christmas special with a story set in snow covered Czarist Russia, while the audience is confronted with daily war updates from modern day Russia. How do you reconcile these two aspects, and do they need reconciliation?

Cover for the original piano score of “Zirkusprinzessin,” 1926.

In the Hannover program booklet Judith Wiemers explains that Zirkusprinzessin is the story of people kicked out of society: in this case, the snobbish Russian aristocracy (and army) considers those outside their ranks people one doesn’t mix with. In a best case scenario, they are good enough to serve and entertain you when you throw money at them, as happens here with the circus artists. The circus being something of a metaphor for those who don’t fit in and have nowhere else to go.

It is a basic set-up that has lost nothing of its universal relevance. It’s a story about privilege and entitlement, i.e. things we are discussing more intensely today than ever. Making the two worlds – the circus as a place of social despair and solidarity among the outcasts vs. the glittery world of the aggressively rich and politically powerful – visible should be the first task of any stage director. Making the arrogant character of “Fürstin Fedora Palinska” as the leading lady in love with the mysterious Mr. X relatable would seem to be task no. 2.

Mercedes Arcuri as Fedora in “Zirkusprinzessin” at Staatsoper Hannover. (Photo: Sandra Then)

Why would the operetta tenor (a role created by Hubert Marischka) fall for such a woman (created by Betty Fischer) – even when she treats him like dirt because of his station? Is there more to her? Is there a moment of change in her that leads to the 3rd act happy-end? Is Kálmán’s lavish love music a hint that behind that icy Fedora façade lies a human being longing for love, or, as she puts it in her entrance number: “Was in der Welt geschieht, immer das selbe Lied, alles, ach alles nur: Nur pour l’amour!”

At Staatsoper Hannover soprano Mercedes Arcuri sings this music with an opulent youthful Puccini voice and ravishing top notes, combined with an interesting timbre in the lower register. Vocally she is a dream Fedora. But she has absolutely no acting ability to make the complicated character and her journey interesting. She stands there, on the huge empty stage in Hannover – decorated with a large chandelier, snowflakes falling down non-stop for atmosphere – as if she’s singing Mimi in La Boheme, not Kálmán or operetta: where one doesn’t just have to sing but needs to act during the many dialogue sections. Ideally, a little self-irony would be helpful. Because this piece is overstuffed with self-referential jokes that need to be delivered with a wink, otherwise everything becomes boring and second-hand.

Marius Pallesen (r.) as the outcast Mr. X in “Zirkusprinzessin” at Staatsoper Hannover. (Photo: Sandra Then)

At her side, there is Marius Pallesen as the tenor Mr. X. His acting might not be much better, but he displays an emotional nakedness and vulnerability (with his open voice and direct delivery of his soaring melodies) that make Pallesen effective in a unique way. He has the wounded posture of someone who has experienced terrible things and is haunted by his past. And he delivers his music in that way to, which is hugely effective.

But conductor Giulio Cilona and stage director Felix Seiler have decided to trim down all the songs and duets. You get one verse and refrain, and that’s it. Even the famous “Zwei Märchenaugen” is over before it really begins. Which feels weird, because you wonder: what’s the point of this production if not to have the glorious music on display at an opera house?

There is no immediately evident other point to the production which is attractively set on an empty stage with a round platform in the middle (= the circus of life) above which a chandelier looms, moving up and down (a bit too often for its own good).

Mercedes Arcuri and the dance ensemble/chorus in “Zirkusprinzessin” at Staatsoper Hannover. (Photo: Sandra Then)

The circus artists, aristocrats and members of the Czarist army look like they are all going to the same Christmas party (costumes and sets by Timo Dentler and Okarina Peters). There is no palpable tension between the groups, no differentiation. Everyone is busy doing old-fashioned “operetta stuff”, without a hint of camp or (!) self-parody.

The story is played “straight”, which is always a bad idea in any operetta. Certainly in this one which recycles Millöcker’s Bettelstudent and revenge plot as a nod to the Viennese operetta tradition which was at the crossroads back in the 1920s – audiences and authors alike wondered if operetta should move in the direction of American musical comedy, revue, opera, or something else. Kálmán, Brammer and Grünwald wrote their next show, Die Herzogin von Chicago (1928), about exactly these questions. And Zirkusprinzessin can be seen from that “quo vadis” perspective, too.

Front page of the magazine “Die Bühne” showing Betty Fischer and Hubert Marischka in their “Zirkusprinzessin” costumes, 1926.

Because they want something novel to show, the production team scrapped the third act, claiming it is too “trivial” after all the high-flying emotional drama of act 1 and 2. So out goes the comic role of “Pelikan” (originally written for star comedian Hans Moser), and Carla Schlumberger appears alone in act 2, looking for her son Toni who has escaped from Vienna to St. Petersburg to marry the circus artist Miss Mable. In Hannover, Carmen Fuggiss plays Mrs. Schlumberger without much comic timing, which makes the scenes with her son Toni (played by Philipp Kapeller with a strong Viennese accent, but little else) almost embarrassingly simplistic.

Miss Mable, the flirty little circus artist, is here a dramatic Nikki Treurniet who looks attractive, but has no idea how to sing 1920s dance music (such as “Wenn du mich sitzen lässt, fahr’ ich zurück nach Budapest”). They all sing Kálmán and the entire Zirkusprinzessin like grand opera. Which kills any musical differentiation and contrast.

Nikki Treurniet as Miss Mabel and Philipp Kapeller as Toni in “Zirkusprinzessin” at Staatsoper Hannover. (Photo: Sandra Then)

To top things off, no one bothers to articulate the words clearly, not even the chorus. You need to read the supertitles to have even an inkling of what’s going on in the music. It seems conductor Giulio Cilona didn’t invest much time of preparing the soloists. Actually, his conducting makes you believe that he didn’t spend much time preparing himself for such an operetta task either. While he has a full symphony orchestra at his disposal, he makes them play the big lush tunes in the most unremarkable way imaginable. Maybe Mr. Cilona should check out the old Robert Stolz recording, just as a reference? Or the recording of Kálmán conducting his own music, to see how is can be done more effectively.

At the end, without act 3, Mr. X does a final circus jump after having been cast away by Fedora. He drops to the stage from far above – and is dead. Which is the moment Fedora seems to realize what she has done. She kneels next to the corpse, holds Mr. X’s hand, and sings their act 1 love song à capella. Which is a strange reference to Maria in West Side Story, it feels out of place here because you can’t have such an emotional melt-down moment after three hours of tame “operetta fluff” (as presented here). Even if the basic idea is interesting.

Marius Pallesen and Mercedes Arcuri in “Zirkusprinzessin” at Staatsoper Hannover. (Photo: Sandra Then)

Why all the second verses have been cut, yet Mr. X. sings “Heut’ nacht hab’ ich geträumt von dir” as an extra solo before his death remains another mystery. That song doesn’t fit into the musical world of Zirkusprinzessin, and it certainly doesn’t fit the sentiments of a suicidal person with all of its joky lyrics.

Which leaves things where? In the program booklet stage director Felix Seiler says that operetta “would never sacrifice its more serious characters to tragedy completely”. Yet, that’s what Mr. Seiler does here. And the effect is … let’s say: questionable. On the plus side, there is wonderful singing from the leading lady and man. There’s a lot of snow coming down in the course of three hours. And some scenes look magically. Plus, Daniel Eggert as the scheming Prince Sergius Vladimir gives a pretty impressive “sinister” performance.

Mercedes Arcuri and the dance ensemble in “Zirkusprinzessin” at Staatsoper Hannover. (Photo: Sandra Then)

Though there is a small dance ensemble, choreographer Danny Costello never uses dance as a central element of this production and there is no choreographed rhythmic “beat” throughout. Which is sad. The “new” finale can’t really compensate for the fact that the staging hasn’t much to say about the basic story. Given the minimalistic sets it all might have worked with different actors on stage, but the company’s intendatin Laura Berman didn’t seem to think it necessary to invest much thought in finding anything “special” for her Christmas special, in terms of casting and conducting. It’s business as usual, nice to look at, but without any further characteristic elements worth reporting on. Most of the reviews in regional papers were pretty damning as a result.

In her program booklet essay, dramaturg Judith Wiemers points out that Zirkusprinzessin has been a hit in Soviet Russia for decades, she mentions that famous black-and-white film version of 1958. There, in the very end when Mr. X is about the jump from the trapeze, Fedora rushes into the circus arena and decides to leave the world of the aristocrats, joining her lover as an outcast and member of the working class. It’s a social message in sync with the socialist realism of operetta behind to Iron Curtain. Miss Wiemers calls this ending “a beautiful – even utopian finale”. Indeed, it is. And I wish there had been a bit more utopia in Hannover.

I am saying all of this hesitantly, because I have seen impressive operetta productions by Mr. Seiler and I very much like the work of dramaturg Judith Wiemers. So where did things go wrong? Maybe Laura Berman has the answers, or Giulio Cilona?

The curtain for the original Viennese “Zirkusprinzessin” production 1926.

Just for the record, the Coburg production by stage director Andreas Wiedermann doesn’t look like it got it right either, in terms of telling a story of emotional or social relevance. So there is definitely room left for others to try again and bring this Kálmán-Brammer-Grünwald blockbuster back with a punch.

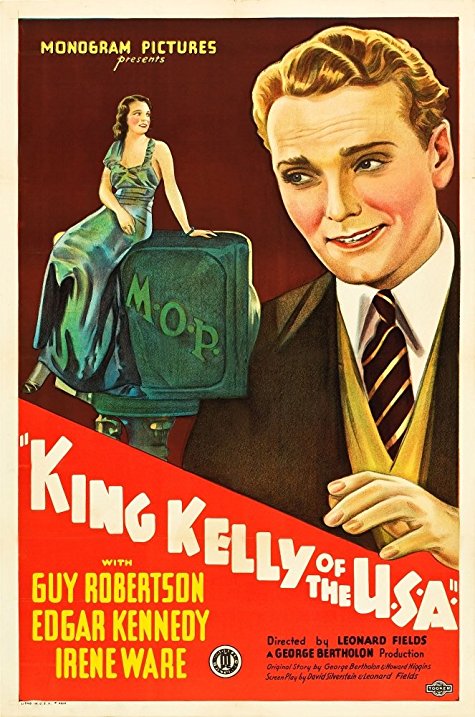

By the way, Zirkusprinzessin was successfully tranferred to Broadway in 1927 by the Shubert Brothers, with an English book by Harry B. Smith, who also translated the lyrics. The production ran for 192 performances at the Winter Garden Theatre, in a staging by J. C. Huffman and Marcel Varnel. Guy Robertson was Mr. X before later appearing in hit shows such as The Great Waltz as Johann Strauss Jr., Desiree Tabor was Fedora. She later appeared in Jerome Kern’s Bavaria themed Music in the Air.

Guy Robertson in the movie “King Kelly”

Perhaps Encores! will give this Broadway version of Circus Princess a modern day reading one of these days, with modern day musical comedy stars? I’m sure Cheyenne Jackson would be a winsome Mr. X. He can certainly act, and sing!

For more information and performance dates in Hannover, click here.

E’ meglio che l’operetta muoia invece di vivere così …