Michael H. Hardern

Operetta Research Center

8 Juni, 2016

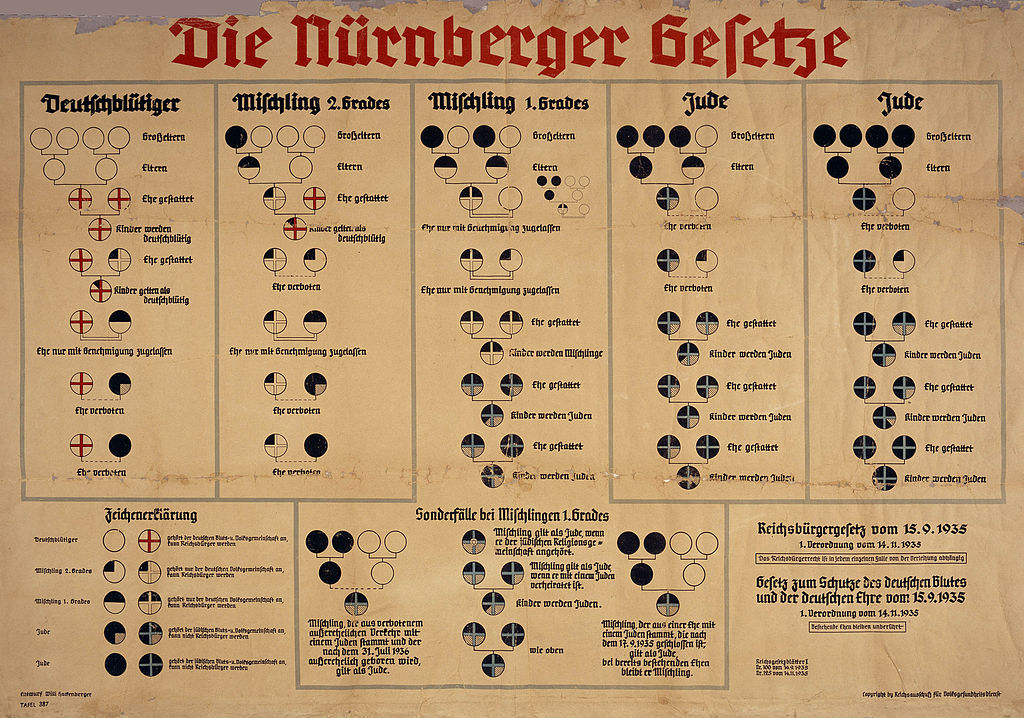

Nuremberg is a special place for a conference that wishes to examine “Operetta in Nazi Times.” Because the so called “Nürnberger Rassegesetze” of 1935 had a severe impact on operetta history, defining who was to be considered “Jewish,” and thus “degenerate” and “unwanted.” Also, Nuremberg’s famous Nazi Parteitag of 1935 – where these laws were passed – is imprinted in universal memory, thanks to Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda film Triumph des Willens.

A chart, outlining the “Nürnberger Rassegesetzte” of 1935.

Now, the opera house in Nuremberg is organizing a one-day conference on June 12, in collaboration with the Forschungsinstitut für Musiktheater of the University Bayreuth. The conference is entitled Leichte Muse im Wandel der Zeit. It is part of the research project “Inszenierung von Macht und Unterhaltung – Musiktheater in Nürnberg 1920-1050,” which roughly translates as “Staging of Power and Entertainment: Musical Theater in Nuremberg 1920-1950.”

The opera house in Nuremberg, 1935.

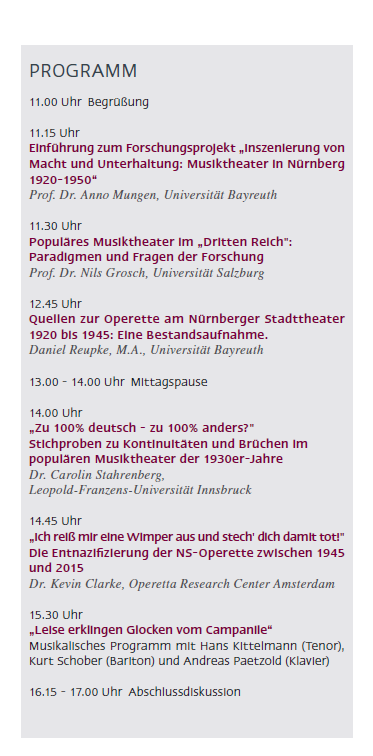

On Sunday at the Gluck Saal of the opera house, there will be six lectures, starting at 11 am. Prof. Dr. Anno Mungen as the host and head of the research project will introduce the topic. He is followed by Prof. Dr. Nils Grosch from Salzburg discussing “Popular Musical Theater in the Third Reich.” Then Daniel Reupke will present source material about the Nuremberg theater situation between 1920 and 1950.

After a lunch break, Innsbruck’s Dr. Carolin Stahrenberg will talk about “100 % German – 100 % Different: Continuities in the 1930s Popular Theater Scene.” Then, Operetta Research Center’s Dr. Kevin Clarke will examine how the works created during Nazis times underwent a “denazification” after 1945, he will talk about the strategies used to eliminate the problematic ideological baggage found in works by Rudolf Kattnigg (Balkanliebe), Nico Dostal (Clivia), Fred Raymond (Maske in Blau) and others.

The conference ends with a concert whose title Leise erklingen Glocken vom Campanile points towards this “denazification” strategy: the popular number from Kattnigg’s Balkanliebe was isolated from the actual show, which was considered “not performable” because of its “Blut und Boden” (blood and soil) message. But the soothing barcarole from the show – out of context – was harmless enough to become a standard in 1950s and 60s operetta programs. At some point, no one remembered what the actual show is about, which is the present-day situation too. But people can still enjoy “the beautiful music,” and do.

On Sunday night, all participants of the conference will attending a performance of Kiss Me, Kate at the Nuremberg opera house. It’s a particularly fitting show, because Kiss Me, Kate started – in Frankfurt and Nuremberg – the musical comedy boom in Germany, that eventually swept away the old operetta traditions and initiated something new, less ideologically tinted.

That said: if you consider how musicals are performed in Germany and Austria, and what kind of new musicals are written there, you realize that the Nazi operetta shadow is far-reaching; in a shocking way.

The schedule for the Nuremberg conference on June 12.

For more information on the program and schedule, click here.