Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

25 September, 2020

This new recording starts overwhelmingly: with gongs, whole tone scales, rhythmic oriental rattling, bouncing horn passages à la Richard Strauss. The Munich Radio Orchestra under conductor Ulf Schirmer plays Leo Fall’s 1001 nights score with a strong element of bombast, and that’s wonderful. Because it makes this cast album sound so much more opulent than all previous recordings of Die Rose von Stambul, where the orchestra was never captured by the sound engineers with such detail and splendor.

The recording of “Die Rose von Stambul” from Munich. (Photo: cpo)

And then we’re right off into the first scene where Kondja Gül (daughter of Kamek Pascha) awakes in her secluded women’s quarters in Istanbul. And what she sings makes it immediately clear why this 1916 operetta is still very poignant today. Kondja laments that she was once “a nice little brown girl” who was allowed to attend “balls and parties”, “play tennis” and “flirt”. But then, one day, she was suddenly told: “You now have to wear the veil!” She wants to get out of this situation that’s supposedly dictated by “morals and traditions“ – and by “the Prophet“.

A young Muslim woman today. (Photo: Muhammad Faiz Zulkeflee / Unsplash)

When her friend Midili Hanum appears and tells her, in a quirky two-step, that the women in Paris are allowed to eye up men in cafés, instead of “hiding at home”, because they are “free from our conservative customs”, the other women join into a rousing revolutionary march: “Von Reformen, ganz enormen, träumen wir am Bosporus!” I.e. they are dreaming of enormous reforms at the Bosporus. And they demand that “the veil must go”, their society should step “out of the dark”.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. (Photo: kultur.gov.tr)

Kemal Atatürk actually made this happen in the 1920s, modernizing Turkey and reforming it into a secular country. Until Erdogan came along, decades later, and turned that development around. Since then there’s been a lot of discussion about religion and state, women covering themselves because of Islamic tradition, female oppression, the patriarchy, modernity etc. Not just in Turkey.

Young contemporary women walking past a Turkish flag. (Photo: Jean Carlo Emer / Unsplash)

A quick reminder: When the Frankfurt Museum for Applied Arts presented the exhibition Contemporary Muslim Fashions in 2019, discussing chādor, niqāb and burka among other things, there was violent protest. The accusation was that Muslim women were not shown as covering themselves out of their own free will, instead Western stereotypes and prejudices of women being suppressed were supposedly reproduced. A social media shit storm demanded that the exhibition be closed, the director sacked and so on. When an academic conference was to be held, discussing some of the central (fashion) points, there was more protest about the question: who is allowed to speak about this topic?

If you wonder what that has to do with Rose von Stambul and the new cpo recording from Prinzregententheater, the answer is this: a stage director friend wanted to do Rose at a West-German theater recently. But he was told by the intendant and dramatug that the story in this operetta was “not his”, that he wasn’t “entitled” to stage it, because it “belongs” to others, i.e. Turkish and/or Muslim women. He, as a white, Christian, German man had to keep away from this piece. (Maybe the intendant was worried about a potential shit storm à la Frankfurt?)

A young man at a barber shop in Istanbul. (Photo: Barna Bartis / Unsplash)

Such identity politics are visible everywhere, also in the oper(ett)a world: who is “entitled“ to sing Aida and Otello and Sou Chong? Are The Mikado or The Geisha “racist”? Are overcome ethnic stereotypes being reproduced in these shows, or in Das Land des Lächelns? Should all these shows be “cancelled”, or at the very least deconstructed? (For more information on the recent Land des Lächelns controvery at Manhattan School of Music, click here.)

At Münchner Rundfunkorchester no one seems to have heard of such questions yet. Or, differently put: conductor Ulf Schirmer is a white, non-Muslim man, and his cast for the “Turkish” roles is in no obvious way connected with Islam or Turkey: Matthias Klink sings Achmed Bey, Kristiane Kaiser plays Kondja Gül, Magdalena Hinterdobler can be heard as Midili, Eleonora Vacchi is Bül-Bül, Christoph Hartkopf plays his Excellency Kamek Pascha (father of Kondja). And then there’s Hanne Weber as Djamileh. Could you claim that Die Rose von Stambul is “their“ story? Are they “entitled“ to tell this story? And if they tell it anyway, do they have anything to say about the explosive aspects?

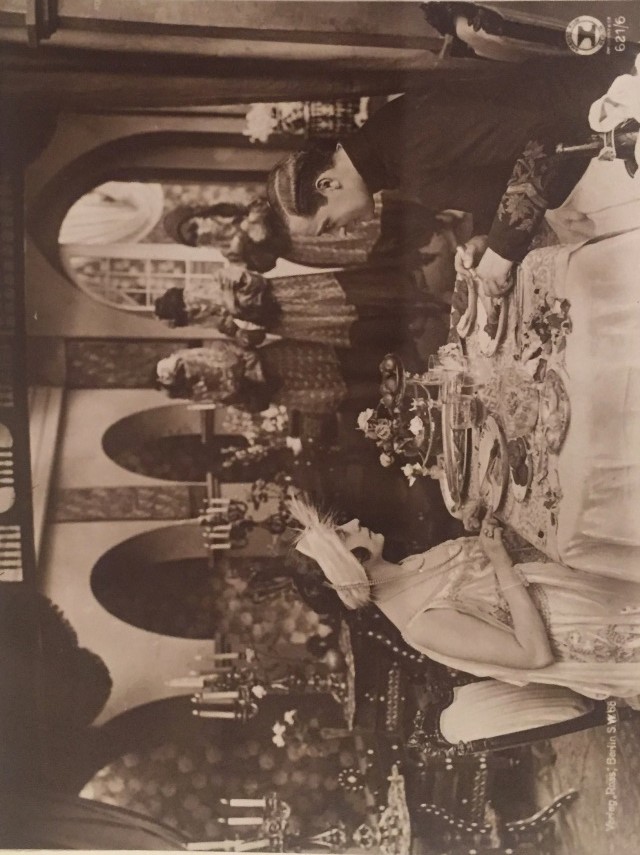

The 1919 silent film version of “Rose von Stambul” with Fritzi Massary (l.) and Felix Basch during the enforced wedding ceremony. (Photo: Robert Wennersten Collection)

In the very worthwhile booklet essay by Leo Fall’s biographer Stefan Frey there is no mention – not even in an aside – about the hijab debates that have made headlines. Or the other hot issue in the show: Kondja is to be married off by her father to a man she doesn’t know and has never before seen. A man she does not want to marry. Frey might have mentioned the recent film A Regular Woman (Nur eine Frau) about the “honor killing” of the young Berlin woman Hatun Sürücü who was killed by her own brother because she left the husband her family had chosen for her, went dancing, stopped covering her head, and started an affair with another man. The film is gripping, and Sürücü’s fate shocking. Not to mention very recent.

With so many cross references in Rose von Stambul to present-day issues, shouldn’t the performers give the lyrics of Julius Brammer and Alfred Grünwald a maximum amount of oomph when they sing about “enormous reforms”? Or is the complete lack of linguistic clarity (you could even say apathy) by Kristiane Kaiser as Kondja and Magdalena Hinterdobler as Midili a ploy to cover traces and keep this show out of discussions and out of the public controversy?

Fritzi Massary emerging from a Turkish bath in the silent movie version of “Die Rose von Stambul,” 1919. (Photo: Robert Wennersten Collection)

Both ladies sing very cultivated, they are pleasant enough to listen to, but they are never ever the rebellious characters they are supposed to be, according to the libretto. There are recordings of the first Berlin cast 1917, released on CD by Truesound Transfers. If you listen to the amazing nuances and cheekiness Fritzi Massary uses as Kondja for numbers such as “Das ist das Glück nach der Mode“ (“This would be a fashionable happiness” – being courted like a European women, not according to Islamic traditions), or when the squeaking Molly Wessely as Midili tells her Western lover “Fridolin, auch wie dein Schnurrbart sticht“ (“Fridolin, how your mustache pokes”), you realize what this new recording lacks completely: any sense that this show is more than just a “cultivated” wish list of great tunes.

Of course the greatest of these tunes, and the most famous number in the score, is the ¾-time duet “Ein Walzer muss es sein“. If you compare the tempo flexibility on the 1917 recording (or the later Richard Tauber recording) with the new cpo version, if you listen to how Massary and Albert Kutzner lose themselves in ecstasy, you realize how pedantic Matthias Klink and Kristiane Kaiser sound under Ulf Schirmer – even though they play the full scene in Munich in which Achmed teaches his young bride how to dance the waltz, “as they do in Vienna”. Just before he tries to rape her, or rather: “demand” that she fulfills her marital duties; which leads us to the next very big issue.

Fritzi Massary and Felix Basch during their first getting-to-know-you dinner, in which she tries to tell him that she wants to we courted like a European lady: from the 1919 movie version of “Rose von Stambul.” (Photo: Operetta Archives, Los Angeles)

Fritzi Massary used her oriental costume back in 1917 to protest with feminist fury against a situation in which husbands could rape their wives – a situation that existed in Germany too and did not change (legally) there until 1997. Massary repeated this in 1919 in the first film version of the show, a film that is sadly lost and of which only stills survive. It seems Kristiane Kaiser as Kondja doesn’t much care about any of this when she sings the finale of act 2. There’s no feminist showdown with the terrorising tenor, only poised tones and dignified phrasing.

The “seducer”, Matthias Klink as Achmed Bey, steps into the footprints of some rather famous predecessors. Most people will probably not remember Hubert Marischka (who doesn’t seem to have recorded the role; there are only photos of him in a dashing Atatürk outfit that he insisted in creating himself).

Hubert Marischka and Betty Fischer in “Die Rose von Stambul”, Vienna 1916.

But many will recall what Rudolf Schock and Fritz Wunderlich sound like in the tenor solos: the rousing waltz “O Rose von Stambul nur du allein, sollst meine Scheherazade sein“ and the “Serenade“ to the “daughters of Mohammed”.

The Munich Radio Orchestra rolls out a red carpet that is more ravishing than any previous recording, and Mr. Kling steps into that carpet carefully with some seductive piano effects. But he lacks the dash of Mr. Schock and the blinding glory of Wunderlich. It would have been a good idea for Mr. Klink to listen to Albert Kutzner in 1917 and copy some of the details he uses to make the text interesting. That way Klink could have easily found a unique portrayal that stands its ground next to Wunderlich/Schock. A good conductor should have worked on this with his soloist(s)!

Andreas Winkler is a very un-poky buffo without grotesque exaggerations (compare him to Eugen Rex 1917). When Mr. Winkler shows up cross-dressed to enter the harem in act 2, singing “Ich bin die Lilly vom Ballett und finde alle älteren Herr’n so nett“, there really needs to be more bounce and humor. More slapstick comedy. In Frey’s Leo Fall biography there is a photo of Ernst Tautenhayn as Lilly, back in Vienna 1916. And you know, just from looking at the pose, the décolleté and the smile, that this scene has more potential, especially in the falsetto phrases of the refrain.

Ernst Tautenhayn as Lilly in “Die Rose von Stambul,” Vienna 1916. (Photo: From Stefan Frey’s “Leo Fall: Spöttischer Rebell der Operette,” Edition Steinbauer 2010)

Why the Bavarian Radio hired baritone Christof Hartkopf for the speaking part of Kamek Pascha is beyond me, he sounds too young and too uncharacteristic for the autoritarian father figure. And then there is Michael Glantschnig in act 3 as the “rhyming” hotel receptionist in Switzerland (where everyone escapes to for the happy ending): again, this is a non-singing role for which the Munich casting office could have easily found an actor with more actual acting abilities and preferably some “Schwizerdütsch”!

On this double CD there’s enough dialogue to follow the story in detail, even though the dialogue is not presented with any theatrical flair. At least there are a few live audience laughs every now and then to keep you awake. (Ralf Eger is listed as director of the dialogue scenes.)

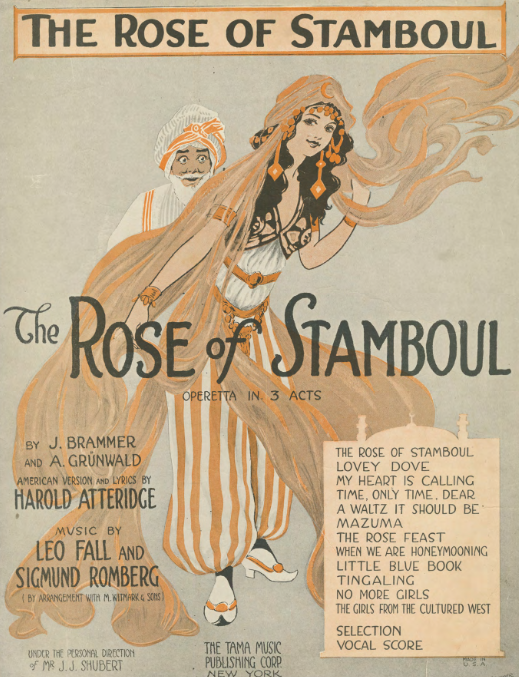

Sheet music cover for the US-American version of Leo Fall’s “The Rose of Stamboul” with extra music by Sigmund Romberg.

In terms of sound quality this new complete recording is far superior to the one conducted by Werner Schmidt-Boelke in 1966, even though Elfie Mayerhofer as Kondja and Rudolf Christ as Achmed are charming. Then there’s the complete recording under Franz Marszalek with Fritz Wunderlich as Achmed and Gretel Hartung as Kondja. It’s an important document of its time, but obviously it’s miles away from any Massary magic. About which Oscar Bie wrote in Berliner Börsen-Courier 1917: “The way she refuses her lover, the way she awakens to a waltz, the way she plays with the children, the way she oozes joi de vivre and combines it with held back lust, those are moments of unforgettable acting skills.”

If you want to get to know Die Rose von Stambul without “unforgettable acting skills” then this new cpo release is perfect. The fact that Ulf Schirmer and BR Klassik, together with Münchner Rundfunkorchester, care so little about “acting” and operetta “skills” in their Leo Fall series is somewhat tragic. Because I doubt there will be another recording of this show in the near future, certainly not one with such an orchestral red carpet. But what’s the use of a red carpet when there are no celebrities walking on it properly?

To read more about Mr. Frey’s biography and Leo Fall’s possible drug addiction, click here.

The 1919 film exists and will be screened at Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna this June. Many things are changed from the operetta but Massary is just as wonderful as a silent film actor as she is on record