Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

14 April, 2018

In a 2018 essay entitled Das Webvideo als Flaschenpost, or “the web video as message in a bottle,” Chris Tedjasukmana examines online video platforms such as YouTube and Vimeo from the perspective of Queer Cinema. He looks at short clips of historic LGBT moments that have popped up online and allow today’s viewer to participate in events that had been totally forgotten or only mentioned in legends and rumors. (His example is a clip of Sylvia Rivera talking at the Christopher Street Day Rally in 1973.) What Mr. Tedjasukmana has to say about such unexpected “re-encounters with the past,” with “moments that have been missed and long forgotten,” very easily applies to operetta, too. Because YouTube is a bottomless treasure trove for operetta history as well, or in Mr. Tedjasukmana’s words: “a global popular home-archive.” It’s an archive that has made some of the greatest operetta performers of all time easily accessible, some for the first time since the original releases of their Schellack discs more than 100 years ago. Re-listening to and re-watching some of these stars of the past today forces us to re-evaluate our standard perception of the genre, as it has cemented itself in the heads of so many people over the years who have grown up with June Bronhill singing operetta, or with the EMI operetta series featuring Anneliese Rothenberger and Nicolai Gedda.

LP cover for the 1958 London production of “The Merry Widow” tarring June Bronhill.

For the longest time, in the LP era, historic recordings were difficult to find. There were copyright issues and royalty questions that were tricky to solve, and no one seems to have cared too much to tackle such legal problems. And why bother with historic recordings anyway if you could sell new recordings for good money?

If you wanted to find anything at all, you had to invest to track down albums of great stars of the early 20th century that some obscure label somewhere in the world might have re-released and might ship to you at a steep price, if you find their contacts to begin with so you could order. Then came the advent of CDs, and various small companies began specializing in restoring historical recordings, the label Duophon Records did so brilliantly with albums dedicated to composers such as Paul Abraham or Ralph Benatzky, but also to singers such as Fritzi Massary or Rosy Barsony, Marta Eggerth or Curt Bois. As glorious as these albums were, they were not cheap. They only covered a small percentage of what there is, somewhere out there in the dark. But at least Duophon albums could be ordered online, we had entered the age of internet shopping and Amazon.

The Duophon album of Paul Abraham, first released in 2001.

Then came the full fledged internet revolution. From a few individual online audio posts of singers, often lovingly illustrated with photo slide shows, the list of available performers on YouTube has grown and grown to enormous proportions. One of the most accomplished restorers of historic operetta recordings, Chris Zwarg at Truesound Transfers, has made a great many of his treasures available online, for free! (Obviously that has, more or less, put companies such as Duophon out of business.)

Being able to click away and listen to the likes of Mia Werber as O Mimosa San singing Die Geisha in 1906 or listening to Oscar Braun and Miss Siegmann-Wolff perform the “Uhren-Duett” from Fledermaus in 1906 is astonishing. Because their ringing voices are so different to what we’re used to in this repertoire today: they sing with a textual clarity you will not find in a single recording made in the past few decades. And they bring such audible personality to their performances, i.e. they are not anonymous singers performing Strauss or Sidney Jones, instead they are fully fleshed out characters in front of the microphone. And they seem to have real fun … it’s astonishing to hear how that fun comes across even a century later.

As you click away you stumble across names you might never have heard of before, for example Marie Dietrich who performs “Spiel’ ich die Unschuld vom Lande” in 1907 with the most unexpected, yet hilariously held long note in the middle of that song. It totally distorts the balance of this Fledermaus number, but this unbalance shows how liberal singers used to treat operetta music, and what unexpected effects you can make with very simple – yet intelligent – tricks. And Miss Dietrich also knows how to shine as a personality in front of a microphone. Even if her top notes come across a strained, it doesn’t matter. Because her bizarre sounds are fully integrated into her all-round performance. That was and is operetta at its very best!

There have been Truesound Transfers albums of Fritzi Massary in the past, and some of the individual tracks have found their way onto YouTube. Most people will be familiar with Massary’s late 1920s and early 1930s recordings which are technically outstanding. Here, on YouTube, there is a 1920 recording of Leo Fall’s Die spanische Nachtigall, one of the great Massary/Fall hits of the day. The voice doesn’t sound as polished as it does in later recordings, but like in the other cases discussed above a strong and irresistible personality is immediately evident. And that personality was the essence of Massary’s operetta style.

Going back even further, there is a 1918 version of Massary as La belle Hélène, sung in German. It’s one of her less familiar roles, but one she scored great triumphs with in the early stages of her career. (Like all true operetta divas, she was an outstanding Helen of Troy.) Unlike Massray’s later more suggestive style (e.g. in “Warum soll eine Frau kein Verhältnis haben?”) she sings more ‘straight forward’ here, more classical in a way. Yet she infuses some very telling coloring into the words when she sings about “humans always having dirty thoughts” and “Gods wanting to bring down female modesty.” It’s a master class in effectively holding back, because this little soliloquy – the Invication of Venus – is supposed to be a private moment in the show. Massary keeps it private.

Chris Tedjasukmana calls YouTube “a universal machine of permanent retro activity.” The clips you find there, from operetta history, are not only audio examples of forgotten singers. Or examples of famous composers conducting their own music, like Kalman conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra in 1940 with his own compositions. Oftentimes YouTube also allow us to see filmed interviews with these stars, interviews they once gave to TV stations, interviews that were broadcast back in the 1960s and 70s, and that then disappeared for the longest time. Many of these interviews have now resurfaced, and they are staggering. I, personally, cannot get enough of the famous German TV interview with Fritzi Massary in her villa in Hollywood. She was in her 80s at the time, but to hear her talk about her pre-emigration career, her partners, the theaters she appeared in before World War 1, brings to life an era that was already lost back then and that is certainly lost today. Yet today it can come back with a single click. And that is nothing short of a miracle, especially if you consider how difficult it was for years to get hold of such TV broadcasts, you had to really hunt for people who might have recorded re-runs and were willing to share a video copy with you. Now you can simple google, and get results, because operetta afficionados from around the world are willing to publicly share their treasures as a gesture of ‘operetta activism’ – you could call this revolutionary!

Moving on from filmed interviews, there are more and more scenes from actual film operettas that are often ignored by the DVD industry. While Americans are accustomed to seeing restored versions of great musical film classics regularly on TV and on DVD, the situation in German has been dismal for years, apparently because the market here for such things is too small to make restorations worthwhile. Now individual fans have taken matters into their own hands and have uploaded segments that can keep you busy for days. They allow us to study, close up, performances of artists such as Max Hansen in drag imitating Gitta Alpar. If Massary as Helena is a master class in itself, then this Hansen/Alpar double is the master class of all master classes. As is the legendary Alexander Girardi appearing on film singing a “Rauschlied,” bringing late 19th century operetta history to the screen (he was after all in the original productions of Der Bettelstudent and Eine Nacht in Venedig, among others).

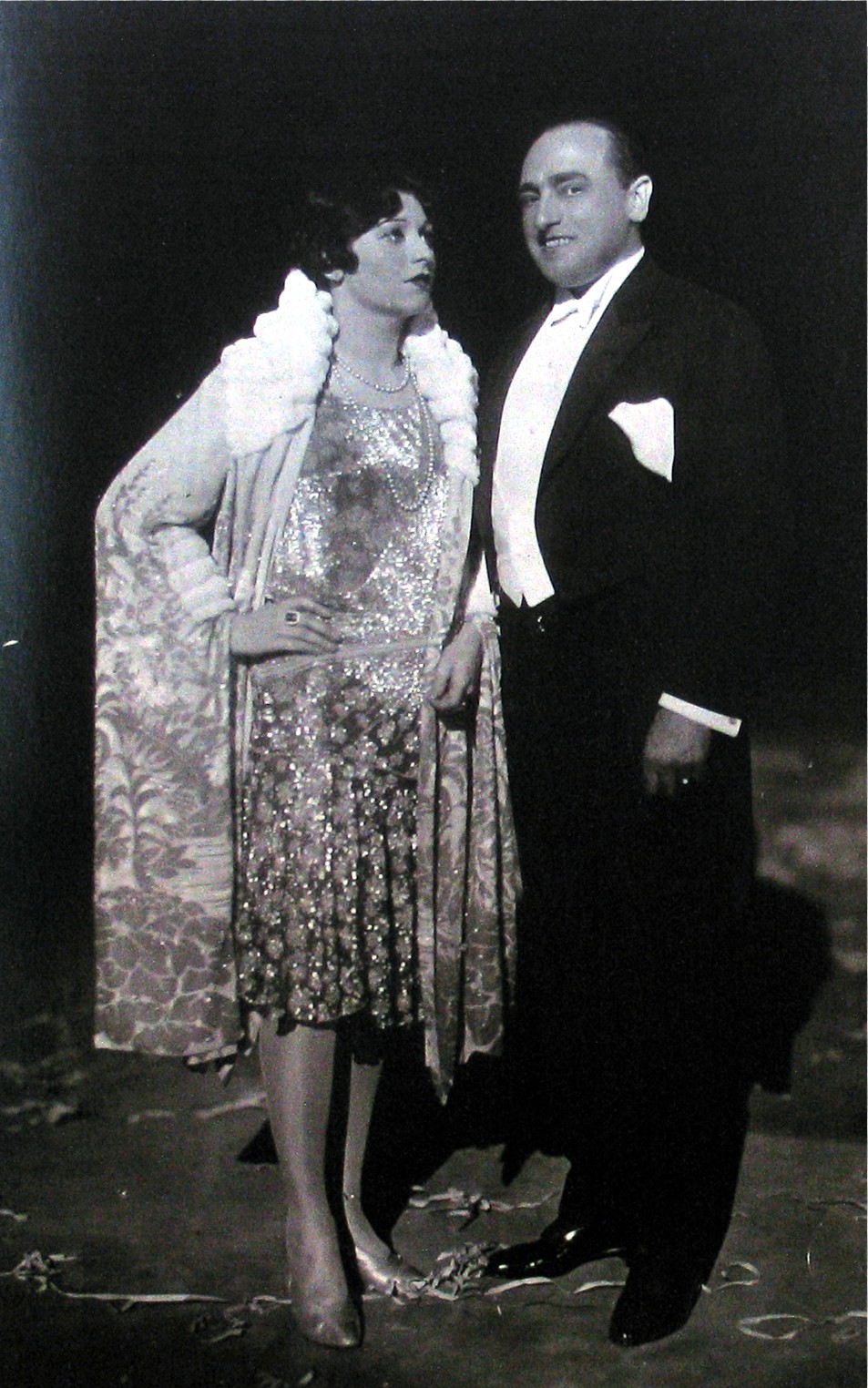

The same applies to Rosy Barsony and Oscar Denes performing in Paul Abraham’s Roxy und ihr Wunderteam. The mastery they display in 1937 shows that totally non-operatic voices combined with outstanding dance abilities can produce singular operetta results. They reminded me of a 1929 review of Johann Strauss‘ Eine Nacht in Venedig. It was performed that year at the Vienna State Opera with an all-star opera cast that included Marie Jeritza, Adele Kern, Lillie Claus, Alfred Jerger and Koloman Pataky, Erich Wolfgang Korngold had newly arranged the score. As a non-operatic guest Hubert Marischka was invited to join to team. Marischka was director of the Theater an der Wien at the time and one of the greatest Viennese operetta stars of the era, the man for who Emmerich Kalman composed most of his legendary star roles in the 1920s, including Tassilo in Gräfin Mariza (1924) and Mr. X in Zirkusprinzessin (1926).

Rita Georg and Hubert Marischka, the two original stars of “Die Herzogin von Chicago” in 1928. (Photo: ORCA)

In reviewing the Strauss production, the Viennese press noted that Marischka “speaks with textual clarity, he creates the right mood and temperament, he’s not afraid to shatter the holiness of the institution now and then with a vulgar joke. The others are far too serious and pompous.” The critics also point out that Marischka is “a virtuoso in displaying all aspects of his charming personality, in contrast to most opera singers he really plays with words, he is an excellent dancer, and he has total body control, which the others don’t.” This total body control, which translates into stage and screen control, is something Barsony/Denes also demonstrate. It’s something you are very unlikely to ever find in an opera singer performing operetta; but this was once a core requirement for any operetta star. Even Louis Treumann as Danilo in Die lustige Witwe (1905) was praised, above all else, for his outstanding dancing abilities; not his singing.

Obviously, I could go on and on about the digital operetta archive to be accessed and enjoyed on YouTube. The many clips to be found there are certainly a “message in a bottle,” a message worth hearing again and worth considering again as a role model. You don’t have to copy any of the singers of the past as a modern performer, but you can learn from them and marvel at the many options they once explored and offered. Many of these options are far more ‘modern’ from today’s perspective that what June Bronhill or Anneliese Rothenberger did in their operetta outings. That’s not to belittle Miss Bronhill (or Miss Rothenberger), but it puts their long-considered ‘standard’ performance style into a historic perspective and allows modern operetta fans to compare and chose for themselves which type of operetta performance appeals to them more. It’s all about options and diversity!

Fritzi Massary in Berlin, 1929. (Photo: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1983-0207-501 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

As a last point, talking about “messages in a bottle,” YouTube and Vimeo do not just allow us encounters with the past, they also make it possible to check out what is happening around the world right now. If you hear or read about new productions in faraway places you can mostly watch trailers that give you some idea of what people are trying to do with the genre.

So you can compare the latest offerings of the Ohio Light Opera and Chicago Folks Opera, for example, with the Vienna Volksoper or Mörbisch Festival, with the Komische Oper Berlin or Gorki Theater or Tipi am Kanzleramt and with what’s going on the far corners of the Czech Republic (with Kalman’s Arizona Lady, for example). And you can marvel at the totally different types of titles and performers companies are offering today, reaching totally different audiences.

One thing they all have in common, though, is that you at home can participate in all of these activities and join the global discussion. Chris Tedjasukmana talks of “queer retro activism” with regard to LGBT videos. You could translate that to “operetta retro activism” and say that operetta history, past and present, has never before been so easily accessible thanks to the hundreds of activists who have made this material available by uploading it, often regardless of copyright details. (Which you can look at from different perspectives.) This elevates the study of operetta history to new heights and offers new possibilities. It’s up to all of us to make good use of them and incorporate these newly accessible treasures into our research and studies.

The results will hopefully be as enjoyable as watching and re-watching these “messages in a bottle,” whether they are a century old or brand new, or as comparativley recent as the 1980s and still a knock-out as these Pirates of Penzance in Central Park, New York. As critic Clive Barnes said, back then in The New York Post: “In a way [the production] is obviously true to the original operetta, but its approach is so radical that it might offend hard-core Savoyard devotees. Without any doubt whatsoever this is Gilbert and Sullivan in a new pop and Broadway guise, and however faithful it may appear it is defiantly different. For me it offered a new awareness for a certain style of operetta that through almost a century of decayed decades I had come to despise. The sheer heady, giddy excitement is perfectly remote from any quasi-operatic version I have seen. And it established the validity of an original, now commonly obscured by the scar tissue of antiquity. There is magic here that bubbles like a witch’s cauldron.”

If this isn’t revolutionary, we don’t know what is. And it’s all there to be studied and discussed today.