Daniel Gundlach

Staatsoperette Dresden / Operetta Research Center

8 December, 2020

When Staatsoperette Dresden presented Kurt Weill’s One Touch of Venus as part of their “Broadway in Dresden” series, in a translation by Roman Hinze and a staging by Matthias Davids, they also prepared a first-ever German language recording of Ein Hauch von Venus. It features Johanna Spantzel in the title role, Peter Christian Feigel conducts the large size orchestra. Now, a collection of essays has been published, analyzing various aspects of the show. One of the essays is by Daniel Gundlach, describing the genesis of this piece and comparing it to other famous Broadway successes, such as Kiss Me, Kate and On the Town. That essay only appeared in a German translation until now, we present the original English version here, in which the author also asks about the operetta aspects of One Touch of Venus.

The book „…wie leise Liebe sein soll“ about Weill’s “One Touch of Venus,” published by Staatsoperette Dresden.

One Touch of Venus is unique among Kurt Weill’s input as his one true musical comedy. As David Savran has noted, “[w]ith its deceptively light comedy and score, Venus might just be the greatest musical Cole Porter never wrote.” [1] The Weill scholar bruce mcclung has also observed that Venus, “as close as he came to a regulation musical comedy… perhaps not coincidentally… enjoyed the longest continuous Broadway run of his American shows.” [2]

If Venus is Weill’s only Broadway musical comedy, how do we assess his other contributions to the American stage? His first theater piece composed expressly for Broadway, 1936’s Johnny Johnson, a collaboration with the Paul Green, is described as a “musical play”; though Knickerbocker Holiday (1938) is also described as a “musical comedy,” its setting and themes are hardly the light-hearted fluff of standard “musical comedy”; The Firebrand of Florence (1944) is a full-blown operetta; Street Scene (1947), in some ways Weill’s most ambitious Broadway work, is described in the published score as an “American opera” and has come to be so regarded; the neglected masterpiece Love Life (1948) is a unique revisioning of vaudeville; and Lost in the Stars (1949), Weill’s last completed theater work, is a “musical tragedy.”

This leaves the uniquely structured Lady in the Dark (1941), which defies easy classification, in that nearly all the music occurs within the context of three mini-operas which occur as enactments of the heroine’s subconscious. Though One Touch of Venus is on the surface the most conventional of Weill’s Broadway outings, it nevertheless is a piece that is full of delicious surprises.

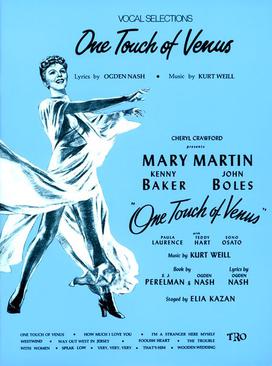

Sheet music cover for “One Touch of Venus” showing Mary Martin in the title role.

Perhaps it would be useful to clarify what exactly constitutes a musical comedy. The simplest definition would be a stage play, normally with relatively light subject matter, to which non-through-composed music is added. Musical comedy is a refinement, a melding even, of two earlier forms, the revue and the operetta. The revue stems directly from vaudeville, in which unrelated sketches and musical numbers were strung together to form an evening’s entertainment. Certainly the most famous example is the various versions of the Ziegfeld Follies, which ran on Broadway yearly from 1907 through 1931, with significant recurrences in 1934 and 1936 (after the producer Florenz Ziegfeld’s death).

Ziegfeld modeled his shows after the Folies Bergère in Paris; a common component of both the Folies and the Follies were the chorus lines of showgirls, in Paris mostly unclad, as well as the musical and comedy sketches of stars, which in New York included such favorites as Fanny Brice, Eddie Cantor, W. C. Fields, and Marilyn Miller.

Probably the most sophisticated iteration of the Ziegfeld Follies was the 1936 edition, which featured songs by Vernon Duke and Ira Gershwin and featured, among others, Bob Hope and Joséphine Baker as well as Brice, a perennial Follies stalwart. Practitioners of the musical revue never aimed for a unifying plot or theme, unlike operetta, which developed out of the French opéra comique, which used spoken dialogue rather than sung recitative to connect the musical numbers. Jacques Offenbach was definitely the most celebrated and sophisticated of French operetta composers, though Gounod, Bizet, Chabrier, Messager, Massé and others also contributed to the form.

Jacques Offenbach riding his success, a caricature from a Paris newspaper.

Eventually the genre traveled to Vienna as well, where it was developed and perhaps surpassed by Johann Strauss II, as well as other skilled composers such as Franz von Suppé and Karl Millöcker as well as, in succeeding generations, the Hungarians Franz (Ferenc) Lehár and Emmerich (Imre) Kálmán.

Operetta became popular in England as well with the unique contributions of W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan, whose works, like Offenbach’s, usually featured pointed satire of contemporary culture.

At the end of the 19th century the genre found its way to Germany, where it took root in Berlin in particular, with composers such as Paul Lincke, Walter Kollo, and Eduard Künneke.

The dashing young composer Paul Lincke.

In the first decade of the twentieth century operettas by Kálmán and Lehár began to be produced on Broadway at the same time as original American works (albeit often by non-native composers) appeared, primarily by Victor Herbert, Sigmund Romberg, and Rudolf Friml. Though original work of Romberg continued to be produced on Broadway even after his death in 1951 (see The Girl in Pink Tights, 1954), by and large operetta productions on Broadway had slowed to a trickle by the mid-1930s.

In general this material had quainter, even old-fashioned subject matter in a musical language that was similarly backward-looking. In his seminal work Show Boat (1927) Jerome Kern provided a link between an operetta plot and the jazzier, breezier songs that were being produced by the Gershwins and Cole Porter.

Original sheet music cover for the 1927 hit “Show Boat.”

Though Rodgers and Hammerstein’s 1943 smash hit Oklahoma! is often called the first integrated musical (that is, the first musical to seamlessly segue from dialogue to dance to song and back again and to use both song and dance to advance the plot), other scholars consider Show Boat to more accurately occupy that position. (Interestingly, Oscar Hammerstein II was also the lyricist for the earlier work.)

Cole Porter occupies a unique position in this pantheon in that, unlike everyone except Irving Berlin, he composed both music and lyrics to his songs, and unlike nearly all composers of musicals including Berlin, he was not Jewish. In addition to his two most famous musicals, Anything Goes (1934) and Kiss Me, Kate (1948; first produced in Germany in 1955 and one of the most popular American musicals here ever since), his other shows include Leave it to Me! (1938; Mary Martin’s first Broadway role, discussed below); Gay Divorce (1932; Fred Astaire’s last Broadway show and his only without his sister Adele); Nymph Errant (1933; only produced in London’s West End, but Porter’s personal favorite among his shows); three further shows that starred Ethel Merman: Red, Hot and Blue (1936), DuBarry Was a Lady (1939), Something for the Boys (1943); and three late-career post-Kate shows: Out of this World (1950), Can-Can (1953), and Silk Stockings (1955), the last his final Broadway show, which starred Don Ameche and Hildegard Knef, the spelling of her surname Americanized as Neff.

Except for Anything Goes and Kiss Me, Kate, Porter’s reputation rests primarily on individual songs celebrated for their urbanity, piquant wordplay, surprisingly rhyming schemes, and double entendres. These are often list songs (“You’re the Top,” “Always True To You In My Fashion”) or narrative songs (“Miss Otis Regrets,” “The Tale of the Oyster”).

One might take particular note here of the unsuccessful Out of this World, based as it is on Amphytrion, making it the one Porter musical in which Greek gods and goddesses make an appearance. Though the tone of this piece is closer to slapstick than Venus’s sleek sophistication, it is interesting to compare the Porter list song “Cherry Pies Ought To Be You” in which two different couples, one amorous (“Cherry pies ought to be you / Autumn skies ought to be you… All of Beethoven’s Nine ought to be you / Every Will Shakespeare line ought to be you”) and one warring (“Withered grass ought to be you / Lethal gas ought to be you… Florida when it rains ought to be you / Pinchers in subway trains ought to be you”) paint comparisons of the other.

Compare this to the negative similes that Ogden Nash, Venus’s lyricist, uses in “How Much I Love You” (“I love you more than a wasp can sting / And more than a hangnail hurts… / As a dachshund abhors revolving doors / That’s how you are loved by me”). Weill’s intention in Venus might not have been to directly emulate Porter, but, in this work he comes closest to Porter’s trademarks, while still retaining the hallmarks of his own particular style.

After the enormous success of Lady in the Dark Weill was once again in search of a new subject for his next theater piece and, typically, he found inspiration in an unusual place: a British satirical novel entitled The Tinted Venus by Thomas Anstey Guthrie, known professionally by the pseudonym F. Anstey. [3]

In the novel a barber named Leander Tweddle places an engagement ring by way of comparison onto the finger of a statue of Aphrodite situated in an off-season pleasure garden. As a result the statue comes to periodic life every evening and involves Leander in a series of misadventures involving the police, a pair of thieves, his fiancée and her mother, and a pair of sisters, one of whom is engaged to his best friend and the other of whom he was once casually courting. These elements form the basis of what was to become One Touch of Venus, though the setting, tone, and themes differ substantially from the source material.

The Venus de Milo in Paris, surrounded by tourists. (Photo: Miquel Rossy / Unsplash)

According to Stephen Hinton, it was Irene Sharaff, the costume designer for Lady in the Dark, who first brought The Tinted Venus to Weill’s attention. [4] Weill was quite taken with the suggestion, initially “envision[ing] it as a neo-Offenbachian operetta” [5] and he suggested the material to the independent producer Cheryl Crawford.

Crawford was one of the most important producers in mid-century American theatre and one of only a handful of women. She had worked her way up through the ranks of the Theatre Guild, where she met Harold Clurman and Lee Strasberg, with whom she had formed the Group Theatre in 1931, a leftist theatrical collective which adhered to the principles of Stanislavski and which produced, among other things, early productions of the work of Clifford Odets. Crawford and Weill had worked together previously on Weill’s first work for the Broadway stage, the aforementioned Johnny Johnson, which was Crawford’s last production with the Group Theatre before she left to become an independent theatrical producer.

A photo from the original production of “Johnny Johnson,” 1936. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Weill had given Crawford informal musical advice when she mounted a revised Broadway revival of Porgy and Bess in 1942, which, unlike the 1935 premiere on Broadway, was enormously successful. (Weill’s exposure to the Gershwins’ work was influential in his desire to produce an American opera, which finally came to fruition in Street Scene.) Crawford and Weill agreed to engage Bella Spewack to write the book of the musical, which was to be entitled One Man’s Venus, while Ogden Nash was engaged to write the lyrics.

Apart from his contribution to Venus, Nash is most known for his light, humorous verse, hundreds of which appeared in The New Yorker between 1930 and 1971, the year of his death. [6] Along with her husband Sam, Bella Spewack’s most famous contribution to musical theatre came with the book to Cole Porter’s Kiss Me Kate in 1948.

Upon receipt of her final draft of the script, Weill and Crawford were dissatisfied with her work and Bella was dramatically fired. At this point Nash took over the writing of the book and suggested a colleague of his at The New Yorker, S. J. Perelman, as his collaborator. Perelman is remembered today primarily as the co-author of two Marx Brothers comedies, Monkey Business (1931) and Horse Feathers (1932). During his lifetime his humorous vignettes were published in The New Yorker and collected in many best-selling books. Sometimes in collaboration with his wife Laura, [7] he wrote numerous Broadway plays between 1932 and 1963.

Perelman and Nash’s script, renamed One Touch of Venus, updated the action to contemporary (that is World War II-era) New York City. The profession of Anstey’s barber was retained, though he now sports the name Rodney Hatch. The conceit of a statue of Venus coming to life was retained, though all the particulars thereof, including her basic character, were changed from the novella. Leander’s fiancée, named Matilda Collum, is good-natured and well-suited to him. Perelman, on the other hand, transforms her into a shrewish and demanding harridan named Gloria Kramer. He also introduces a foil to the barber, a wealthy and eccentric art collector named Whitelaw Savory, who disdains any art that is not cutting edge.

There is one piece of ancient art that Savory does not disdain, and that is a statue of the Anatolian Venus, which he saw years before and which reminds him of the girl that got away. In an effort to recapture the memory of that lost love, he has his two thugs, Taxi and Stanley, obtain the statue for him in Smyrna and transport it to his art gallery.

Seated Woman of Çatal Höyük: the head is a restoration, Museum of Anatolian Civilizations. (Photo: Wikipedia)

The moment after the statue arrives, the barber Rodney Hatch shows up to give Savory a shave and a trim and, left momentarily alone with the statue, spontaneously slips the engagement ring he has purchased for Gloria Kramer onto the statue’s finger. At this point the statue comes to life and announces her undying devotion to the man who has released her body from its enslavement in marble. In spite of Rodney’s entreaties, Venus refuses to return the ring which has brought her back to life.

As well as being the goddess of love, this Venus is also a pragmatist: in her first encounter in corporeal form with Savory (who, though he does not recognize her as his statue, which he believes has been stolen by Hatch, is struck by her resemblance to his lost love), she delivers one of the most famous lines of the piece, “Love isn’t the dying moan of a distant violin – it’s the triumphant twang of a bedspring.” [8]

To act as a foil to Venus, Perelman and Nash also crafted a secondary female role, Whitelaw’s competent, efficient, and sassy assistant named Molly Grant. It’s the sort of wisecracking role that would have been played in Hollywood by Eve Arden. [9] Molly delivers the two songs that are the comic highlights of the piece, the title tune (which contains the show’s wittiest lyric, “Mix a little touch of goddess / With a little touch of damsel / And life is just a goddess damsel cinch”) and the caustic “Very, Very, Very” (which in its targeting of “the contrasting moral values of the very, very rich and the common folk” [10] addresses the same concerns that Weill and Brecht addressed in their joint creations).

As Ethan Mordden puts it, “[s]he’s the only reasonable person in the whole play, and she helps ground the fantasy in that she’s the sole character to figure out that [Venus] is the missing statue. She isn’t even shocked: she’s amused.” [11] She tells Rodney that Venus “was the nicest goddess I ever met.”

Though Venus confesses to Rodney that his “ring only brought us together. It had no power to make me love you,” in the end that love is not enough to resolve the enormous differences between an ordinary barber who longs for a life in the suburbs and the goddess of love come to life. (In fact, Rodney’s dream of life in the suburbs described in “Wooden Wedding” is an evocation avant la lettre of conformity of suburban life that became a way of life in the US in the 1950’s.) Venus returns to her roots and Rodney is left alone to mourn her desertion. Until, that is, Venus’s contemporary double shows up for classes at the Whitelaw Savory Foundation of Modern Art and the two are instantly drawn together as the curtain falls.

Attitudes among the cognoscenti in the world of modern art are satirized in the musical’s opening number, “New Art Is True Art,” with lines such as “New art is true art / The old masters slew art… / How are they to be trusted? / They must have been maladjusted… / The best of ancient Greece / They were centuries behind Matisse.” Sophisticated patrons of the arts would have been cognizant of the increased cultural visibility of contemporary visual art, thanks in large part to the opening of the new Museum of Modern Art in 1939, and the media presence of its director Alfred H. Barr, a self-styled tastemaker.

In Venus’s book, Alfred H. Barr and the MoMA are clear stand-ins for Whitelaw Savory and his self-named Foundation of Modern Art. In 1929 at the age of only 29 Barr was named the director of the Museum of Modern Art, which opened the doors of its new home in 1939. Like his fictional counterpart, Barr was both a curator and an instructor in art history, having taught undergraduate art history at Vassar, Wellesley, and Princeton between 1923 and 1927. Indeed, one of his courses at Wellesley was called “Tradition and Revolt in Modern Painting,” a subject one could well imagine Savory teaching. In his position at MoMA Barr was responsible for important exhibitions on Picasso, van Gogh, Cubism, Dada, photography, modern architecture, the American and European avant garde and Bauhaus.

According to Naomi Blumberg, Barr was “a risk taker and a polemical figure; among his colleagues he was known for having a dictatorial manner and an unrelentingly dogmatic approach.” [12] Perhaps as a result of his contentiousness, in 1943 he was removed from his directorial post at MoMA, though he remained with the institution in an important acquisitional function until 1967.

Theatregoers in 1943 might have derived amusement and satisfaction at recognizing Barr in the elitist Savory—a type who is anything but savory—who is given self-important lines such as “I shall fight on, gallant Don Quixote that I am… until the hydrated monster of bad taste lies dead on the doily of every tea shoppe in the land!” One must wonder, given Savory’s dismissal of any art that is not “modern,” at his determination to acquire the Anatolian Venus statue. The simple reason, as he confesses to Molly, is that the figure depicted reminds him of a lost love. As he tells her, “That’s quite a tragedy for a collector, Molly. I lost the girl but at least I’ve got the statue.”

In fact, when Savory sings the song “Westwind,” the musical material is based on the music first heard when the statue of Venus comes to life. The use of triplet quarter notes (an important component of several of Venus’s songs, as will be discussed later) combines with ambiguous harmonies “to express a sense of intense yearning.” [13]

As Geoffrey Holden Block describes the genesis of the music illustrating Savory’s Venus fixation:

In the midst of his sketches for Lady[in the Dark], including a draft for “My Ship,” Weill sketched a tune that with some modifications would eventually become “Westwind.” In the early stages Weill used its melody solely for the “Venus Entrance” music (and he would continue to label this tune as such throughout his orchestral score). Long after the entire show had taken shape, the music of the future “Westwind” was still reserved for Venus. At a relatively late stage Weill decided to show Savory’s total captivation with Venus musically by adopting her tune as his own. After their first meeting his identity is now fully submerged in the woman he idealizes. [14]

In contrast to her characterization in Weill’s music, the title character in The Tinted Venus is a threatening, vengeful, vindictive figure who alternates between her daytime marmoreal form and her increasingly dangerous resumption every evening of embodiment in flesh and blood. Tweddle, as the object of her affections, is very much in the line of fire. This forms a stark contrast with Weill, Nash, and Perelman’s Venus: she may have an imperious streak such as befits any goddess (she does, after all, cause Mrs. Moats, Rodney’s landlady, to keel over in a faint, and, worse, Gloria to disappear without a trace, which gets Rodney arrested at the first act curtain for Gloria’s suspected murder), but mostly she is just an amorous (if superhuman) gal who is trying to find her place in contemporary New York and will do anything within her considerable power to get her man to succumb to her.

Additionally, Stephen Hinton has suggested that Weill may have felt drawn to Anstey’s original The Tinted Venus because of his “lifelong sympathy for female characters who view themselves as outsiders.” [15] Indeed, he cites examples extending nearly Weill’s entire output, from Royal Palace to Lost in the Stars that foreground such women. An ancient goddess unable to make sense of the contemporary Manhattan into which she has been suddenly reincarnated (see in particular her first song “I’m a Stranger Here Myself”) would fit in comfortably (or not) in that company.

For their Venus, Weill and Crawford had a very specific star in mind: the glamorous German expat icon Marlene Dietrich. Weill had earlier, in fact, at Dietrich’s request, offered her two free-standing songs (“Es regnet” and “Der Abschiedsbrief”), which she unfortunately never performed. [16] While first the Spewacks, and later Perelman and Nash, worked to create a viable book, Crawford and Weill went through an elaborate courtship ritual to convince Dietrich to portray Venus. Though Crawford did manage to get her to sign a contract to commit to the show, in the end, Dietrich rejected the role, stating that she found it “too vulgar and profane.” She further stated that, as the mother of a nineteen-year-old daughter, she could hardly be expected to be publicly exhibit her legs (though when her daughter was younger this was never a deterrent).

Thus Weill and Crawford found themselves with time closing in on them and no star for their show. Someone suggested Mary Martin, whose sole Broadway credit was a secondary part in Cole Porter’s Leave It to Me (1938), which, coincidentally, was based on a play by Sam and Bella Spewack, and which starred Sophie Tucker and the comedy team of William Gaxton and Victor Moore (who in their day headlined an astonishing number of hits, including Anything Goes, Louisiana Purchase, and the Gershwin’s two political satires, Of Thee I Sing and Let ’Em Eat Cake).

In a secondary role, Martin became famous for her performance of the suggestive “My Heart Belongs to Daddy.” It has been suggested that incongruous innocence of her delivery stemmed from her lack of understanding of the smutty undertones of the text. Martin’s performance netted her the cover of Life magazine and led her to Hollywood, where she spent several years as an underused MGM contract player.

Frustrated, and seeking to reestablish herself on the Broadway scene, she moved back to New York in 1942 with Richard Halliday, her husband-manager and daughter (leaving behind her son from a previous marriage, Larry Hagman, to be raised by her own mother) in pursuit of a Broadway vehicle. She and Halliday had already gambled and lost on two musicals which had died in out-of-town tryouts (as well as turning down the lead in what was to become Oklahoma!), but even after an initially reluctant Crawford offered her the part she was not at all convinced that she was the right fit for the part.

Finally a trip to the Metropolitan Museum to observe the wide range of Venus statues convinced her that she might actually be pretty and sexy enough to play the goddess of love. Hearing Kurt Weill play the song “That’s Him” for her cemented her decision.

Three external influences helped shape Mary Martin’s performance and make her a Broadway icon in this, her first starring role. When Elia Kazan, Venus’s director, whose previous professional experience in musicals had been as an actor in the original production of Weill’s Johnny Johnson, asked Martin how she intended to approach the role, she was at a loss for words. Finally she told him that in her film work she had always discovered her character by first finding her walk. This was certainly to be the case with Venus. In this she had the assistance of two extraordinary women whose contributions to the piece helped lift it far above standard musical fare. First of these was Agnes de Mille, fresh off her triumph in Oklahoma!

American dancer and choreographer Agnes de Mille (1905-1993) playing ‘The Priggish Virgin’ in the ballet “Three Virgins and a Devil” on Broadway, 1941. (Photo: United States Library of Congress)

Even if, as discussed before, it is not really the first integrated musical, with de Mille’s choreography, narrative dance is foregrounded more than in any musical that had preceded it. In One Touch of Venus, dance plays an equally significant, though less iconoclastic, role. De Mille took it upon herself to help Martin find the right physique du role. She placed a great emphasis on Venus’s legato movements. Particularly in the first extended ballet piece, “Forty Minutes for Lunch,” which takes place in the arcade of Rockefeller Center, a strong physical contrast is established between Venus’s languorous movements and those of the commuters and workers who dash around her. According to Kara Anne Gardner,

[f]or the concept of the show to come across to audiences, Venus had to appear different from all of the characters on the stage. She was a shrewd observer, commenting on the strange ways of whose who surrounded her. She had to stand differently, walk differently, appear aloof. It took Martin some time to develop these qualities, but when Venus opened on Broadway, Martin captivated audiences in all her songs and dances. She undeniably became the show’s star, which worked very effectively since she was portraying a goddess who existed in a realm far above that of mere mortals. De Mille played an instrumental role in helping Martin succeed. [17]

One of the dancing commuters in the “Forty Minutes” ballet who appeared again in the concluding “Venus in Ozone Heights” and “Bacchanale” numbers was the now-legendary Sono Osato. Osato, born in the United States to a Japanese-born father and an American mother of French and Irish heritage, had begun her career at fourteen in the 1930s as the youngest dancer in the history of the Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo and continued with the Ballet Theatre (currently known as American Ballet Theatre). She was making her Broadway debut as the Première Danseuse in Venus. Immediately after Venus Osato would go on to make Broadway history performing the role of Ivy Smith the “Exotic Miss Turnstiles” in On the Town, the Leonard Bernstein-Betty Comden-Adolph Green wartime hit.

In notices for both Venus and On the Town, Osato’s physical beauty and luminous presence are highlighted, as well as her exoticism. It was indeed highly unusual for a young woman of Japanese heritage to be featured onstage following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. This is further highlighted by the fact that the following day Osato’s father Shoji, a photographer, was arrested at his home on the trumped-up suspicion of him being a spy. He was subsequently permitted to leave his homebase of Chicago only under special dispensation (permission to attend his daughter’s Broadway debut was denied). [18]

For a brief time Osato was obliged to perform under her mother’s maiden name (Fitzgerald) because of the enormous backlash against the Japanese, citizens or not. In this context, it is indeed extraordinary that she was chosen by de Mille, Crawford, and Weill to make her Broadway debut in One Touch of Venus, and to be awarded such accolades for her work. [19]

Osato, more well-versed in movement than Martin (to say the least), offered to assist her colleague during breaks in rehearsal with finding the proper physicality for Venus, an offer Martin gladly accepted. With Osato’s help, “Martin learned how to throw her shoulders back, open her arms wide, tuck in her bottom, and plant her feet firmly.” [20] The onstage interactions of Venus and Osato will be further considered below.

A further substantial influence on Martin’s performance came through the intervention of the American fashion designer Mainbocher (né Main Rousseau Bocher). The designer, in his mid-fifties, had returned from Paris to the United States in 1940 after establishing himself as an influential couturier with an important clientele which included the Duchess of Windsor, among others.

Having already costumed Leonora Corbett for her appearance as Elvira, the ghost in Noël Coward’s Blithe Spirit in 1941, [21] Mainbocher was engaged to design gowns for Mary Martin to increase her appearance of godliness. He created fourteen different costumes for the actress and for the rest of his life became her personal and professional designer, famously creating her costumes for The Sound of Music (1959), as well as Ethel Merman’s for Call Me Madam and Rosalind Russell’s in Wonderful Town. Instead of downplaying Martin’s long neck, Mainbocher emphasized it, as well as exposing as much of her bare skin as he possibly could, particularly her back, as, he stated, “a concession to the fact that after all, Venus is never a clothed lady.” [22]

The actress Ruth Gordon described the appeal of Mainbocher’s couture in a profile on the designer in the New York Times: “He conceals, disguises, enhances, but never makes a fuss about it.” [23] In addition, depending on which story one believes, either Mainbocher, Elia Kazan, or Lotte Lenya was responsible for the staging of Venus’s song “That’s Him.”

In Martin’s version of the story, when trying to convince Mainbocher to act as her costume designer, Martin pulled up a chair directly in front of him, sat down side-saddle and sang the song to him, at which he purportedly exclaimed that he would indeed costume her on the condition that she would always perform the song exactly as she had done for him.

According to Kazan in his autobiography, the idea was his alone. In a third version of the story, [24] it was Lenya herself who gave assistance, at her request, to the relatively inexperienced Martin in finding the most effective way to put the song across. Whoever was responsible for staging it this way, it was an extraordinarily intimate moment and helped contribute to the success of both the song and the show.

Osato’s danced roles in the two Venus ballets served to advance the plot in important ways. In the first, entitled “Forty Minutes for Lunch,” she portrays a harried office worker whom Venus takes under her wing, revealing the fine art of seduction in several easy lessons. Osato’s character takes advantage of these gestures when a sailor appears and the harried worker is transformed into a seductive nymph. When the 40-minute lunch break is over, the other workers, who have paused to observe the seductive encounter between the two, resume their frenzied demeanor and, with a wistful backward glance, Osato’s character rejoins their ranks. As Kara Anne Gardner observes,

[t]his brand of humor that de Mille capitalized on in “Forty Minutes” fit perfectly with the tone set by Weill and Nash in their comic songs. But there was something deeper under the ballet’s surface. De Mille’s choreography, coupled with Weill’s music, makes us long for what Venus has to offer; not just her seductiveness, but her slower pace and her grace of movement. [25]

In the second extended ballet, “Venus in Ozone Heights” and the “Bacchanale” that immediately follows, the tables are turned in the relationship between Osato and Venus. In this narrative ballet, Venus ponders the utter confirmity of what married life with Rodney will be like and the imagined reality is not to her liking. In this sequence, Osato appears as a goddess beckoning Venus back to her position of delectable authority in ancient Greece. Eventually in the “Bacchanale” portion, gods, goddesses, nymphs, and satyrs overtake suburbia; at the conclusion an aviator carries Venus away from her humdrum life as a housewife back in time to her origins as a deity.

Agnes de Mille took an unusually strong lead in the overall shape of One Touch of Venus, including the music itself. During rehearsals she is said to have suggested to Weill that a sea shanty was needed at the end of Osato’s encounter with the sailor. Weill obliged her by incorporating the traditional tune “What Shall We Do with the Drunken Sailor,” one of only two points in the score of “literally quoted vernacular music.” [26]

Elia Kazan, the ostensible director of the production, found his role effectively usurped by de Mille. In his book Kazan on Directing, he describes his take on the situation:

I believe Miss de Mille, whose dances were brilliant, was the most dominating personality I ever worked with, so dominating in fact that I was reduced to a kind of stage manager who watched her work in amazement and arranged the lights and stage space to her bidding. I soon became weary of this kind of subservient role, and after my next musical [Weill’s Love Life (1948)] I decided to admit that this was not my best field. [27]

Kurt Weill and de Mille appear to have had an exceptionally good working relationship and complemented each other’s strengths. What is indisputable is the unusually high level of Weill’s involvement in every aspect of the first production. He was, as Mark N. Grant describes, “not only its composer and orchestrator but its de facto co-director and creative co-auteur.” [28] In his selection of subject matter, in his (albeit unsuccessful) courting of Marlene Dietrich for his Venus, in his active role in the shaping of the script, in his at the time unique role as orchestrator of his own score as well as serving as his own dance arranger, in his contribution to the lyrics of the score (it was he who suggested to Nash the use of the line from Shakespeare’s As You Like It—“Speak low, if you speak love” [29]—in what has become the show’s undying popular standard), Weill did much more than simply provide the tunes for the show. According to Grant, “Venus is perhaps the first show where the composer became the ‘muscle’—a case study in backstage Realpolitik, with Weill outflanking the director and guiding not only the creative team but ultimately the show itself.” [30] Further, Grant observes that Weill “was at heart a man of the theater, and his stated goal was to become the leading composer of the American stage, eclipsing Richard Rodgers, whom he regarded as his inferior.” [31]

Alongside Martin and Osato, who were widely considered the primary stars of the show several other prominent performers were featured. Portraying the barber Rodney Hatch was the radio and film performer Kenny Baker, whose credits include, in 1939, both the D’Oyly Carte film version of The Mikado and the Marx Brothers’ At the Circus (also released 1939). According to Cheryl Crawford’s biographer, Milly S. Berenger, his displays of anti-Semitism caused friction between him and Perelman. [32] Upon retiring from performing shortly after appearing in Venus, Baker became a Christian Science practitioner.

John Boles, who appeared as Whitelaw Savory, was an actor who had begun his career on Broadway in the 1920s before becoming a Hollywood leading man, is probably best remembered today for his appearance as Victor Moritz in James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931). Other memorable film roles included the early film musicals Rio Rita and The Desert Song (both 1929), three Shirley Temple vehicles, and as the male lead opposite such stars as Irene Dunne, Gloria Swanson, Barbara Stanwyck, and Rosalind Russell. By the early 1940’s his film career had virtually dried up and he returned to Broadway to take on the role of Savory Whitelaw, his last appearance on the Great White Way and one of his last as an actor.

Teddy Hart, who played the secondary role of Taxi Black, one of the two thugs responsible for carrying out Savory’s dirty work was the brother of the lyricist Lorenz Hart. A diminutive figure, Hart had a successful career on stage (where he portrayed roles in, among others, the Rodgers and Hart show The Boys from Syracuse and Gogol’s The Inspector General) and screen. His biggest success was in the Runyonesque Three Men and a Horse, which he originated on Broadway and for which he won a Screen Actors Guild for the film version.

Taxi’s cohort, the laconic Stanley, was played by Harry Clark, a former physical education teacher and factory worker whose first success in the union sponsored musical revue Pins and Needles in 1937 inspired him to take up a career as a professional actor, during which he portrayed comic roles in B films, on stage, and on television. Clark also appeared in the original production of Kiss Me, Kate, in which, as Mark N. Grant notes, he sang in “Brush Up Your Shakespeare,” a number Cole Porter “does seem to have modeled” on Venus’s “The Trouble with Women.” [33]

For the role of Molly, Crawford and Weill hit the jackpot with the casting of Paula Laurence. Laurence was fresh off her successful Broadway appearance portraying the sidekick stripper named Chiquita Hart opposite Ethel Merman in Something for the Boys, Cole Porter’s wartime musical comedy. She garnered superb notices for Venus, and for her delivery of the two comic numbers previously described. [34] Throughout her long career, which began on Broadway as Helen of Troy in Orson Welles’s Federal Theatre Product production of Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, Paula Laurence appeared in a range of entertainments, singing in such glamorous boites as Le Ruban Bleu and playing supporting roles in Junior Miss, Cyrano de Bergerac, Volpone, Ivanov, and Funny Girl. In 1953 she married the theatrical producer Charles Bowden, [35] whose Broadway credits included everything from Bernstein’s Trouble in Tahiti to Lily Tomlin’s one-woman Broadway show to numerous works of Tennessee Williams, the most important of which was The Night of the Iguana, in which Laurence herself understudied Bette Davis. [36]

Later in life she also gained acclaim as a journalist and appeared in a few choice film roles and guest spots on television, including the Gothic soap opera Dark Shadows.

Noteworthy is the breadth of musical styles that Weill deployed in One Touch of Venus. The two ballets discussed earlier as well as the three additional extended dance sequences form the structural backbone of the show. The stylistic range deployed in the songs themselves is extraordinary for any Broadway musical, especially for one as outwardly conventional as this one. In the comic songs alone, we veer from Molly’s breezy, sassy observations in “One Touch of Venus” to the more staccato emissions of her “Very, Very, Very” to Rodney’s characteristically more awkward and innocent comic tones in “How Much I Love You” and its musically identical but emotional inverse “That’s How I Am Sick of Love.”

The other purely comic songs range from “Way Out West in Jersey” to “The Trouble with Women” each of which represents a different musical genre. “Jersey” may not be a familiar song type to contemporary audiences, but it represents a Western parody along the lines of “Bronco Busters” from George and Ira Gershwin’s Girl Crazy (1930) or “Way 21 Out West on West End Avenue” from Rodgers and Hart’s Babes in Arms (1937) or even Cole Porter’s “Don’t Fence Me In” (first heard in the 1934 film Adios Argentina).

Stephen Hinton also suggests that Weill and Nash might have been taking direct aim at “smash hit of the previous season, Oklahoma!” in this “patronizing, city-centric parody of [its] country-bumpkin world.” [37] In a not-dissimilar vein, “The Trouble with Women” is a barbershop quartet number in which the inherent sexism of the overall theme in a conservative musical language is offset by the final proto-feminist observation “the trouble with women is men.”

The other comic number “New Art Is True Art” reflects the views about Modern Art discussed earlier. Certainly the most peculiar number in the musical is “Doctor Crippen.” The conceit of the first act finale is that Rodney is suspected of having murdered Gloria and Savory holds an (apparently impromptu) “Artist’s Ball” at which the centerpiece is a staged musical re-enactment of the 1910 crime of the real-life murderer Hawley Harvey Crippen. The music foreshadows “Progress” in Love Life and directly evokes “The Saga of Jenny” from Lady in the Dark, though it lacked the dazzling star power that Gertrude Lawrence brought to the latter number.

The short-circuited Gothic horror of “Doctor Crippen” certainly represents an artistic challenge to those who seek to revive One Touch of Venus, with the curtain falling on the corpse of Crippen appearing out of nowhere to sing the words “I gave not only my life / But that of my wife / For the love of Ethel Le Neve!” Interestingly, Mark N. Grant asserts that this number anticipates by a generation the Music Hall-Grand Guignol style of Sweeney Todd. [38]

By contrast to this outlier of a number, Venus’s music forms the emotional center of the musical. The quarter note triplets employed in the “Venus Awakening” theme discussed in relation to “Westwind” are important musical building blocks in two of Venus’s other songs, including her opening number “I’m a Stranger Here Myself.”

Here the title character is given not just a series of snappy rhetorical questions by Nash, but an unusual song structure by Weill, set to a snappy syncopated beat. Stephen Hinton elucides:

[T]he overall form of the song resists conventional categorization. Whereas the opening strophe more or less adheres to the thirty-two measure model with an eight-measure bridge/release passage, the following sections effectively elide the beginning and end of the chorus while expanding the bridge component. In other words, each of the three choruses in Venus’s verseless song has its own unique release, each more artful than the last. [39]

Venus’s second song, “Foolish Heart,” finds her still full of questions about this new world into which she has been thrust. She is trying to discover why Rodney appears to be immune to her divine charms. Her doubts are expressed in three-quarter time, the language of pure operetta, in stark contrast to the syncopations of her first song. Venus questions her attraction to Rodney and the vagaries of romantic love (“Poor foolish heart / Crying for one who ignores you… / Flying from one who adores you”).

Venus’s final song, “That’s Him,” deliciously ungrammatical as it is, is, according to Geoffrey Holden Block, “representative of Weill’s earlier ideal by distancing the singer from the object and providing a commentary on love rather than an experience of it. Venus even speaks of her love object in the third person.” [40] Her affair with Rodney has finally been consummated and the goddess is, at least at this moment, delighted with her lover’s pure ordinariness (“He’s as simple as a swim in summer, / Not arty, not actory / He’s like a plumber when you need a plumber / He’s satisfactory.”)

A possible reason for this distancing is Venus’s “ambiguity towards Rodney… despite his endearing qualities, [he] remains an unlikely romantic partner, especially for a Venus.” [41] A significant part of this song’s appeal, according to Mark N. Grant, is the “kaleidoscopic orchestration… almost as if the orchestra is itself an actor mirroring Venus’s lines.” [42] In performance the ambiguity inherent in this song can express itself as a charming insouciance. [43]

In contrast, Venus’s duet with Rodney, “Speak Low” is perhaps the greatest love song in the entire Weill canon. Set to an alluring rumba beat, the melodic contours emphasize the quarter note triplets encountered in “Stranger Here Myself” and the “Venus Awakening” theme, which expand against the syncopations of the accompaniment. The longing implied in the music finds its ultimate expression in the text, which reveals the existential angst of the love between human and mortal as a struggle against time and mortality (“Our summer day withers away too soon… Our moment is swift, like ships adrift we’re swept apart too soon… Time is so old and love so brief / Love is pure gold and time a thief… The curtain descends, ev’rything ends too soon”) Indeed, the truth of this lyric extends to all love relationships, and this existential angst expressed against the undulations of Weill’s endlessly seductive melody accounts for its continuing popularity.

Opening night notices for One Touch of Venus were almost entirely favorable, even ecstatic, but when awards season came around, the show did not sweep the field. The precursor to the Tony Awards, which were first awarded in 1946, was the Donaldson Awards, which ran from 1944-1955. One Touch of Venus was cited for various Donaldson Awards, including one for Mary Martin for Actress in a Musical, Agnes de Mille for Dance Direction, Sono Osato for Female Dancer, and Kenny Baker for Supporting Actor in a Musical. Interestingly it won no musical awards. Best Musical was awarded to Carmen Jones, which also won two awards for Oscar Hammerstein II for both Book and Lyrics. Kurt Weill lost for Score to Georges Bizet (!) for Carmen Jones, which also won for Sets and for Costumes. Perhaps not surprisingly, Elia Kazan was also overlooked for the Director of a Musical citation.

Though they appear to be strange bedfellows, One Touch of Venus and Carmen Jones do share one similarity: they fall, at least peripherally, into the subgenre of World War II musicals. (One must remember that Carmen works in a munitions factory and Joe, Bizet’s Don José, is stationed in the Air Force.) Other works produced during this period that fall into this category include Cole Porter’s aforementioned Something for the Boys, Irving Berlin’s revue This is the Army (1942, filmed 1943, itself a retooling of his WWI revue Yip Yip Yaphank) and of course On the Town, produced in Broadway in 1944, based in turn on a scenario used in Leonard Bernstein and Jerome Robbins’s ballet Fancy Free.

Though it is not primarily concerned with military personnel, as are the other pieces, Venus does bear certain earmarks of these other works. As Stephen Hinton points out, background characters, including the sailor with whom Sono Osato dances in “Forty Minutes for Lunch” and the aviator who spirits Venus away at the conclusion of the “Bacchanale,” appear throughout the piece. [44] In the context of the uncertainty of war, songs like “I’m a Stranger Here Myself” and, especially, “Speak Low” acquire an almost unbearable poignancy, especially when deriving from the pen of a composer who was living out the final years of his all-too-short life in imposed exile from his country of origin.

It is perhaps surprising that the seemingly lightweight One Touch of Venus achieves the same musical sophistication and philosophical profundity of his other less formulaic American work. It is sincerely to be hoped that the Staatsoperette’s revival of Venus, “golden age Broadway’s reply to the racy sex comedy of filmmaker Ernst Lubitsch” [45] puts the lie to Geoffrey Holden Block’s assessment that “Weill’s popularly designed American works remain unrevived and perhaps unrevivable.” [46]

[1] David Savran, “Performance Review: One Touch of Venus in Dessau,” Kurt Weill Newsletter, Volume 28:1 (Spring 2010), 18.

[2] bruce d mcclung and Paul R. Laird, “Musical sophistication on Broadway: Kurt Weill and Leonard Bernstein,” in William A. Everett and Paul R. Laird, eds., The Cambridge Companion to the Musical, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 170–1.

[3] Anstey’s first success as a writer was the 1882 story Vice Versa, in which a father and son switch bodies. This theme has been co-opted by popular culture many times since, often without crediting Anstey for the source material. The first Vice Versa film, a British silent, appeared in 1916; a second British version from 1948 is directed by Peter Ustinov and stars Roger Livesey and Anthony Newley, while a later Hollywood version dates from 1988 and is directed by Brian Gilbert and stars Judge Reinhold and Fred Savage.

[4] Stephen Hinton, Weill’s Musical Theater: Stages of Reform (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 310.

[5] Mark N. Grant, “One Touch of Venus: An Appreciation,” The Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, www.kwf.org/pages/ww-one-touch-of-venus-an-appreciation.html (accessed 13.02.2019).

[6] Fascinatingly, the first of his collections of verse, published in 1938, years before his work with Kurt Weill, is entitled I’m a Stranger Here Myself (New York: Little Brown and Company).

[7] Laura West Perelman was the sister of the writer Nathanael West, who married Eileen McKenney, one of the two sisters in Wonderful Town, the 1953 Leonard Bernstein-Betty Comden-Adolph Green musical revived by the Staatsoperette Dresden in 2016. The couple were killed in a gruesome car accident on December 22, 1940, four days before the theatrical adaptation of Ruth McKenney’s short story collection My Sister Eileen, the basis for Wonderful Town, opened on Broadway.

[8] Perelman’s first work for Broadway, the musical revue Walk a Little Faster, starred Beatrice Lillie and featured music by Vernon Duke and lyrics by Yip Harburg. His last contribution to musicals was the creaky book to Cole Porter’s final work, the 1958 TV musical Aladdin, which starred Sal Mineo, Anna Maria Alberghetti, Cyril Ritchard, and Basil Rathbone.

[9] In fact, Arden plays this very role in the pallid 1948 film version that, though it features the exquisite vision of Ava Gardner as Venus, alongside Robert Walker (a non-singing Hatch, now given the first name of Eddie), the crooner Dick Haymes (in the role of Hatch’s best buddy Joe Grant, apparently added so he can sing a truncated version of “Speak Low,” which cuts between scenes of Haymes and Gardner, dubbed by Eileen Wilson), and Tom Conway as Whitelaw, is stripped of almost all of Weill’s music and suffers irreparably from the excision.

[10] Geoffrey Holden Block, Enchanted Evenings: The Broadway Musical from Show Boat to Sondheim (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 154.

[11] Ethan Mordden, Beautiful Mornin’: The Broadway Musical in the 1940s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 161.

[12] Naomi Blumberg, “Alfred H. Barr,” Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/biography/Alfred-H-Barr-Jr. (accessed 13.02.2019).

[13] Hinton, 314.

[14] Block, 140.

[15] Hinton, 310.

[16] In fact, Dietrich never sang a note of Weill’s music before a public audience, though while she was considering the part of Venus she did perform “Surabaya-Johnny” privately for Weill and Crawford, to her own accompaniment on the musical saw, as well as later for her onstage audition for Venus, where composer and producer realized that, for Dietrich’s voice to carry in the theater, discreet miking would have to be employed.

[17] Kara Anne Gardner, Agnes de Mille: Telling Stories in Broadway Dance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 52–3.

[18] Carol Oja, Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 135.

[19] Sono Osato died on December 26, 2018 at the age of 99.

[20] Gardner, 53.

[21] Corbett was, coincidentally, considered for the role of Venus after Dietrich had turned down the part.

[22] Mainbocher, quoted in “Mary Martin’s Dress,” Life, November 22, 1943, 58.

[23] Quoted in Gilbert Millstein, “Mainbocher Stands for a Fitting, ” New York Times, March 25, 1956, 36.

[24] Gardner, 54.

[25] Ibid., 60

[26] Hinton, 310. Hinton incorrectly assesses this as the sole example of quoted music in the score, though the introduction to “Way Out West in New Jersey” unambiguously if briefly quotes the American folk song “Turkey in the Straw.”

[27] Elia Kazan, Kazan on Directing (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), 149.

[28] Mark N. Grant, “One Touch of Weill,” liner notes to recording of One Touch of Venus (Jay Records, CDJAY21362, 2014), 12.

[29] Grant, “One Touch of Weill,”, 19.

[30] Grant, “One Touch of Venus: An Appreciation.”

[31] Grant, “One Touch of Weill,” 18.

[32] Milly S. Berenger, A Gambler’s Instinct: The Story of Broadway Producer Cheryl Crawford (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2010), 80.

[33] Grant, “One Touch of Weill,” p. 15.

[34] In 1983 she appeared under the ægis of the New Amsterdam Theatre Company in a concert version of One Touch of Venus in New York’s Town Hall reprising the role she created 40 years earlier. Her performance of “Very, Very, Very” from this single concert performance can be heard on YouTube (https://youtu.be/5j92-zkv4z8).

[35] In 1937, during his early career as an actor, Bowden appeared in the ensemble in performances at the Manhattan Opera House of Weill’s The Eternal Road, a musical pageant commemorating the history of Jewish life directed by Max Reinhardt with book and lyrics translated from Franz Werfel’s original German.

[36] In fact, Laurence and Bowden were so close to Williams that, as his death, he named them the guardians of his institutionalized sister Rose, the inspiration for Laura in The Glass Menagerie.

[37] Hinton, 313.

[38] Grant, “One Touch of Venus: An Appreciation.”

[39] Hinton, 313.

[40] Block, 150–1.

[41] Block, 152.

[42] Grant, “One Touch of Weill,” 17.

[43] The composer himself captures the charm of this song like no other interpreter in a demo recording graced by his charming German-accented English (https://youtu.be/UzkTIo4uECk, accessed 14 February 2019).

[44] Hinton, 307–8.

[45] Grant, “One Touch of Venus: An Appreciation.” 29

[46] Block, 136.