Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

6 March, 2016

For many people in the classical music world, the name of Nikolaus Harnoncourt is almost sacred. The conductor who died at the age of 86 today – as the Austrian television reported – was a pioneer of the period instrument movement. And his performances (and recordings) of Monteverdi operas, as well as Bach cantatas, are legendary. In his quest for “correct revival of misinterpreted masterworks” Harnoncourt also turned to operettas, most notably those of Offenbach and Johann Strauss. The results were disastrous, mildly put. They show a total disregard to historical facts that make you wonder: if this is the depth of his research into “period style,” how serious can anyone take his Monteverdi and Bach?

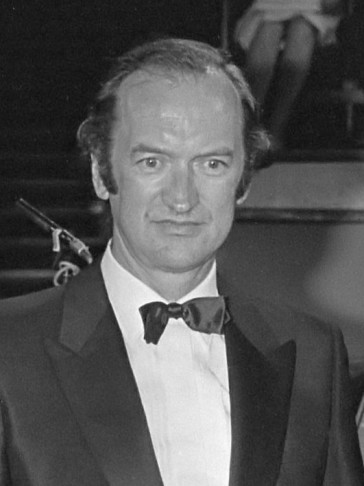

Nikolaus Harnoncourt receiving the Amsterdam Erasmusprijs in 1980. (Photo: Marcel Antonisse/Anefo, Nationaal Archief)

This is not the time and place to belittle the general achievement of Johannes Nicolaus Graf de la Fontaine und d’Harnoncourt-Unverzagt, who had retired from performing in December after a period of illness. At the height of his fame and after he had worked his way through the classical music catalogue, Harnoncourt turned to operetta. He had worked as a cellist with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra in the 1950s, and had witnessed Robert Stolz conducting Strauss waltzes. That, to Harnoncourt, was a role model, and a connection with the historic pre-war past. After all, Stolz had been at the Theater an der Wien in the early 20th century and had know practically everyone in the operetta business, including Johann Strauss. At least, that’s what Stolz claimed.

Of course, the Stolz style of the 1950s and 60s is the polished style of that era, it has nothing to do with the way waltzes or operettas were performed in the 1920s or before. You just have to listen to the many available historic recordings to be well aware of that. But these recordings were not available in the 50s and 60s, so Mr. Harnoncourt could be forgiven for jumping to the wrong conclusions.

When he later performed and recorded Die Fledermaus, based on a so called “critical edition” of the score, he used a cast composed entirely of opera singers. Even though a quick glance at the original 1874 Vienna reviews would have shown him that not a single opera singer was among the original performers at the world premiere at the Theater an der Wien. Harnoncourt didn’t care. And the resulting double CD with Edita Gruberova as Rosalinde – the Marie Geistinger role! – is one of the all-time low points in the discography of this famous show.

The singing, and playing of the Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam, are neither “informed” in any historical way, nor can they stand up – as classical opera interpretations – to the recordings by Herbert von Karajan or Robert Stolz (or Clemens Krauss).

His Offenbach DVDs are equally terrible. There is a Belle Hélène from Zurich with Vesselina Kasarova in the title role. If you have ever watched this performance, you will be aware that it is an incredible bore. Harnoncourt sacrifices the zaniness and madness of the piece for a very “stale” look-at-how-intellectual-we-are performance. When he later tackled Gerolstein at his own festival, the Styriarte, the results were similar.

No one seemed to mind, though. And no one seems to ask any questions. If Harnoncourt said this was historically correct, it was accepted.

That’s not to say that there are no interesting Strauss recordings by him. His disc with the Berlin Philharmonic of Johann Strauss pieces offers a fascinating program of Berlin related titles, including the overture of the original version of Eine Nacht in Venedig. But the execution of the program is nowhere near as fascinating as the selection of the titles themselves.

Nicky Wuchinger in “Der Vetter aus Dingsda”. (Photo: Theater Bremen)

Now Mr. Haroncourt is dead. His passing marks the end of an era, hopefully; an era where famous conductors thought they could just use their name and fame to present operettas, without any real research or any real ideas regarding the genre. It is reassuring to know that today we have conductors like Florian Ziemen or Adam Benzwi who delve into challenges such as Eduard Künneke, Franz von Suppé or Gustav Kerker (Ziemen) or Paul Abraham and Oscar Straus (Benzwi) in a way Harnoncourt never did. With singers such as Nicky Wuchinger, Alen Hodzovic, Katharine Mehrling or Dagmar Manzel. These cast choices, and the musical choices that go with them, surpass anything Harnoncourt ever did in the field of operetta.

So let’s look positively at the future. And remember Harnoncourt for the great things that he did, his Beethoven cycle on disc for example. And let’s take his operetta outings as a warning for how not to do it, ever again.

RIP!

He would not have liked this article….. ;-)

He did not like Mahler either. Calling his “ich, ich, ich” music distateful. That, sort of, says it all.