Kurt Gänzl

The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre

30 June, 2015

Of the great opéras-bouffes of Offenbach’s early years, the one which has suffered the most inexplicable eclipse in the 20th century is Geneviève de Brabant. Whilst Orphée aux enfers and La Belle Hélène still hold the top of the market in musical and opera houses round the world, La Grande-Duchesse and the not-so-bouffe La Périchole surface from time to time, and marginally more imaginative houses are occasionally tempted into a Barbe-bleue, a Pont des soupirs or a Les Brigands, Tréfeu’s hilarious burlesque of the medieval age has followed the other most celebrated medieval parody of the era, Chilpéric, into obscurity.

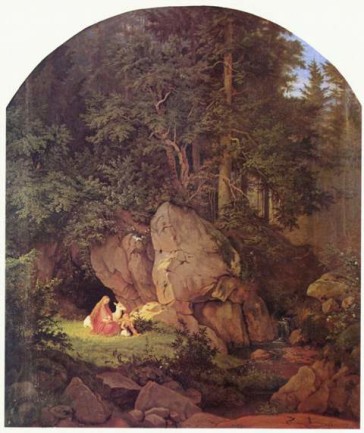

“Genoveva in the Forest Seclusion” by Adrian Ludwig Richter, 1841. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Geneviève de Brabant was the heroine of a favourite tale from the Legenda Aurea (The Golden Legend), a collection of saints’ lives compiled in the 13th century by the Italian monk Jacobus de Voragine, which had won particular popularity in variant versions in Germany (by Ludwig Tieck) and in France, where it had appeared in a burlesque forme (‘complainte bouffe’) on the stage of the Palais-Royal as recently as 1851 (15 March). The wife of Count Palatine Sigfried of Brabant, in the days of Charles Martel, Geneviève was accused of infidelity and chased into the Ardennes forest where she gave birth to a son. The babe was suckled by a white doe before the Count discovered the accusations to be false and brought wife and son home.

Lise Tautin in 1858.

Tréfeu stayed close to the old tale, but told it with burlesque humour rather than saintly drama. His Geneviève (Mlle Maréchal) is the victim of Duke Sifroy (Léonce)’s bosom buddy, Golo (Desiré), who has systematically distracted Sifroy from his conjugal sex life with the hope that he, Golo, will, in the absence of a legitimate heir, become the next Duke of Brabant. The pretty little pastrycook, Drogan (Lise Tautin), bakes a virility pie for the Duke which puts a fathering flicker into his eye, and Golo has to move swiftly to put Sifroy off his stride. He counters the danger by accusing Drogan of dilly-dallying with Geneviève. Then, just to complicate matters, Sifroy is dragged crossly off to the crusades by Charles Martel (Guyot), and, since best buddy has had his ear the last, he goes off repudiating Geneviève and leaving Golo as regent. The abandoned heroine takes refuge from the lubricious villain in the forest. There she meets a crazy jack-in-the-box hermit and has a generally comico-melodramatic time, whilst her husband – who has got no closer to Palestine than Asnières – is holed up with Martel and his mates, having a very convivial time with a rough and tough lady called Isoline. However, he gets home in time to checkmate Golo, rescue the blameless Geneviève, and hand over the termagent Isoline to her long-lost husband, who is none other than the horrified Golo.

“Geneviève de Brabant” as seen at the Theatre de la Gaité.

In the very first version of Geneviève, as produced in 1859, the part which would become Drogan in the later rewrites was a multiple rôle, Mlle Tautin appearing as Mathieu, as Gracioso (a page), as Isoline and also as `le chevalier noir’ and `la bohémienne’ in the many disguises the plot involved. Another rôle, that of ‘le jeune Arthur’, played by Bonnet, was also due for a quick extinction, as Geneviève was altered and made over into its definitive version.

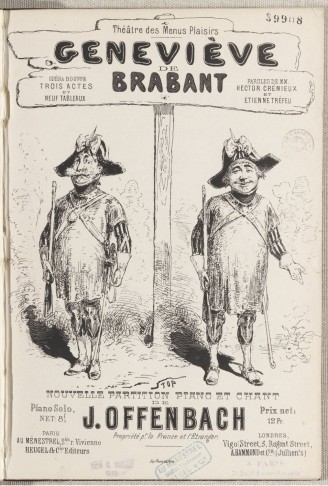

The cover of the piano score for “Geneviève de Brabant.”

Offenbach’s score was a delicious mixture of the broadly burlesque and the charming. What became Drogan’s rondo du pâté (‘Salut! Noble assemblée’), vaunting his potent pie, Sifroy’s nonsensical crowing Couplets de la poule and Charles Martel’s arrival to a merry boléro (‘J’arrive armé de pied en cap’) were amongst the happiest bits of burlesque, whilst pieces such as the superb three-soprano Trio de la main et de la barbe and Drogan’s serenade to Geneviève (‘En passant sous la fenêtre’) supplied the beauty, and the swingeing march finale which saw the Carolan army depart for Palestine, the booming climax. In the original layout, Mlle Tautin also indulged in a Chanson de la bohémienne, a hymn to Geneviève and a Rondo des jeux and Bonnet had a ‘fable de l’enfant’. There was, as yet, no gens d’armes duo for, in this early version, the two comical law enforcers had not yet been tacked into the action.

The 1859 Geneviève de Brabant did not have the same huge and instant success that Orphée aux enfers had done, and after 50 performances the composer/producer took the show off and replaced it with a hasty pasticcio revue. In spite of this, foreign producers were still interested and the first to move was the ever-ready Karl Treumann in Vienna. Treumann mounted an uncredited adaptation (possibly his own) at his Theater am Franz-Josefs-Kai under the title Die schöne Magellone. He himself played Sifroy – now called Siegfried, Therese Schäfer his wife, Magellone, Anton Ascher was the villainous Ulfo and Herr Grois played Charles Martel whilst Fr. Majeranowska played Isoline who, in this version, was still also the page, Grazioso, the gipsy girl and the black knight. Knaack appeared as ‘little Arthur’ and Hopp was Narcziss, the court poet. Die schöne Magellone‘s popularity was limited, but it nevertheless went on to be played in Berlin and in Prague in German, and in Hungary in Hungarian (ad Endre Latabár) with Vela Szilágyi, József Kovacs, Jenö Toth, Rosa Víg, János Parthenyi and Gyula Virágh featured in the Budai Népszinház’s original production.

Grabuge and Pitou as men-at-arms, Théâtre des Menus-Plaisirs, 1868; drawing by Draner. (Photo: Wikipedia)

If the beginning had been only mildly promising, however, things soon looked up. In 1867 Offenbach, Tréfeu and Hector Crémieux put together a new, enlargened and slightly less extravagantly burlesque three-act/nine-scene version of Geneviève de Brabant which was mounted by Gaspari at the new Théâtre des Menus-Plaisirs (25 December). Most of the original score was maintained, but there were some additions made, including the veritable double-act for two goonish gens d’armes (‘Protéger le repos des villes’) which would become the show’s long-range hit, and the Asnières scene was exapanded to include a yodelling tyrolienne and a dance divertissement. Zulma Bouffar took the now star rôle of Drogan with Mme Baudier as Geneviève, Gourdon as Sifroy, Daniel Bac as Golo, and Ginet and Gabel in the low comedy rôles of sergent Grabuge and fusilier Pitou. Once again, the piece was only a fair success in Paris, but this time the rest of the world took a little more notice, and this time (and in more or less this form) Geneviève de Brabant became an international hit.

The ‘new’ Geneviève was given a rather more faithful German-language rendering under Strampfer at Vienna’s Theater an der Wien (ad Julius Hopp) soon after the end of the Paris season. Albin Swoboda (Siegfried), Lori Hild (Genovefa), Jani Szíka (Martell), Carl Adolf Friese (Golo), Marie Geistinger (Drogan) and Blasel and Rott as the gens d’armes headed a starry cast, and there was a spectacular ballet, ‘Die drei Lebensalter’, interpolated into the sixth of the seven scenes in which the high-jinks at Asnières was replaced by an ‘Altdeutscher Narrenabend’. It was played 12 times.

Program for the New York production by Jacob Grau, 1867, on sale at Amazon.com (Photo: Amazon)

Conversely, Geneviève’s American production was a notable success. Jacob Grau’s newly imported French opéra-bouffe company introduced the piece at the Théâtre Français with Rose Bell starring as Drogan, Marie Desclauzas as Geneviève and Bourgoin and Gabel as the gens d’armes. They were so successful that H L Bateman’s previously all-conquering opéra-bouffe company, headed by Lucille Tostée, found its audiences at Pike’s Opera House sadly depleted, and the canny Bateman, having reaped the rewards of introducing La Grande-Duchesse and the can-can to America, swiftly sold out his interests.

The French actress Marie Desclauzas. (Photo: Kurt Gänzl Archive)

Geneviève proved to be the backbone of the new company’s repertoire (L’Oeil crevé, Fleur de thé, La Vie parisienne, La Grande-Duchesse, Chilpéric, M Choufleuri) and it was played more than 100 times during their season, provoking the burlesquers of Kelly and Leon’s Minstrels to mount a Gin-ne-veve de Graw, with Leon impersonating Rose Bell, at their famous minstrel house (2 January 1869), and Dan Bryant to come out with the felicitously titled Geneviève de Bryant.

The Broadway success, however, was nothing to that which the piece won in Britain. Music-hall manager Charles Morton and wealthy bookmaker, Charles Head, had gone into businesss producing opéra-bouffe at the old Philharmonic Music Hall in suburban Islington and Morton allied himself with rising star Emily Soldene and adapter/director H B Farnie to produce Farnie’s version of Geneviève de Brabant. With Soldene as Drogan, Selina Dolaro (Geneviève), John Rouse (Sifroy), Henry Lewens (Golo) and Edward Marshall and Felix Bury as the gens d’armes, Farnie’s production of Geneviève caused the kind of sensation that Orphée had done in Paris (but not in London) and that only Chilpéric of French pieces had even approached in England. The English adaptation of the ‘very amusing but very indelicate’ piece was lauded to the skies, the gens d’armes duo (in Farnie’s famous translation ‘We’re public guardians, bold yet wa-a-ry’), the Serenade, and the Balcony duo became the hits of the era, and Soldene and Dolaro the idolized heroines of the London stage, as the piece played on at its out-of-the-mainstream theatre for a remarkable first limited season of 175 performances, before heading off round the country.

Hervé and Emily Muir as Chilpéric and Frédégone in London.

Henry Hersee hurried out another version of the show for Liverpool, and others (Edward Adams, John Grantham &c) followed suit, but it was the Farnie version which was the hit. It returned to the Philharmonic after its tour for a second run which allowed it to total an amazing 307 London nights by 30 March 1873. The following year it was back again, for a season at the Opera Comique (18 April) with Soldene, Rouse, Marshall and Bury all still in their original rôles, and, after the buxom Emily had given her version to New York — the city’s first English-language performances of the show, and its first sighting of genuine opéra-bouffe in English — it was mounted there again in 1876 (20 March) with the star still featured in her favourite rôle. In 1878 (23 January) the Philharmonic brought their big hit back, with Alice May as Drogan, but Soldene reclaimed her own when she starred in a glamorous production at the Alhambra later the same year (16 September) alongside Lewens, Thomas Aynsley Cook and Constance Loseby, and again, one last time, at the Royalty Theatre in 1881, a whole decade after she had first squeezed into the tights of the plump little page. Soldene played Drogan for the last times in San Francisco in 1890 and in Sydney in 1892, and and her most famous number, the Balcony duet, at galas and benefits till the end of her life.

Australia followed Britain’s example, and a localised version of Farnie’s Geneviève de Brabant was mounted there by W S Lyster (ad Garnet Walch) in 1873. Alice May (Drogan), Armes Beaumont (Sifroy) and Carrie Emmanuel (Geneviève) featured in a version which played fast and loose with both text and music, but which was undeniably successful through 15 performances. Following the Melbourne season, the show was due to be seen in Sydney, but the traditional pantomime period was nigh. Willie Gill at the Queen’s solved the problem of the latest hit by simply interpolating half Geneviève‘s music into his home-made pantomime, but the Royal Victoria Theatre’s B N Jones went further and presented what was basically Geneviève as a putative pantomime, equipped with a harlequinade, under the title Geneviève de Brabant, or Harlequin King of the Bakers, or Four-and-Twenty Baker Boys Baked in a Pie, When the Pie Was Opened… (26 December 1873). Miss May repeated her Drogan alongside Henry Hallam (Sifroy), Sam Poole (Golo) and Miss Lambert (Geneviève) through a fine 24 nights. Australia later saw Soldene’s Drogan, for Geneviève de Brabant was one of the prime pieces in the prima donna’s repertoire when she visited Australia and New Zealand, equipped with the usual exaggerated publicity of the era (`as performed by her over 500 consecutive nights at the Philharmonic, London’) and one of her original gens d’armes, Edward Marshall. Edward Farley (Cocorico, ie Sifroy), the lanky J H Jarvis (Golo) and Rose Stella (Geneviève) took the other main rôles.

Whilst Geneviève had been going on to become the rage of Britain, back in France Offenbach and Tréfeu had had another go at proving to Parisians that they should be making it an equal success there (Théâtre de la Gaîté, 25 February 1875). Adolphe Jaime joined the rewriting team on this occasion, and the piece was expanded with a goodly dose of the kind of spectacle that had served Offenbach productions well on earlier occasions. The fourteen scenes and tableaux now included ‘a divertissement of nurses and babies’ in act one, a fourth-act visit to an enchanted fairy garden where a pageant of the heroes and heroines of poetry and drama was displayed before the genius of the place, and a huge parade was included to allow the use of a vast and expensive array of armour which the composer-producer had had made for his disastrous production of Sardou’s La Haine. A special rôle, Briscotte, was written in to allow the appearance (with songs, some new Offenbach, some from her repertoire) of the celebrated heroine of the cafés-concerts, Mlle Thérésa, alongside whom Mme Matz-Ferrare played Drogan, Christian was Golo, Mdlle Perret Geneviève, and Scipion and Gabel were the gens d’armes. The production inspired a ‘folie-vaudeville’ Geneviève de Brébant at the Théâtre Déjazet (Grangé, Buguet, Bernard, plus some of Offenbach’s music 18 March) but it proved to be far too luxurious ever to break even and, although it ran more than 100 nights, it broke the bank. However, if Offenbach had failed thrice to make a success out of his witty and tuneful work, Fernand Samuel proved at the last that it could be done. In 1908 he mounted a version of the last version of Geneviève de Brabant for 58 nights at the Variétés with Jeanne Saulier (Drogan), Max Dearly (Golo), Guy (Sifroy), André Simon (Martell) and Geneviève Vix (Geneviève). The merits of the piece were, at last, agreed on by French audiences, but in the three-quarters of a century since, Paris has not again seen Geneviève de Brabant.

In habitual style, the Spanish borrowed Tréfeu’s libretto and attached a fresh score to it for a Genoveva de Brabante produced in Madrid in 1868.

Austria: Theater am Franz-Josefs-Kai Die schöne Magellone 3 April 1861, Theater an der Wien Genovefa von Brabant 9 May 1868; Germany: Friedrich-Wilhelmstädtisches Theater 1 July 1861; Hungary: Budai Népszinház Genoveva 11 May 1864; USA: Theatre Français 22 October 1868, Lyceum Theater (Eng) 2 November 1874; UK: Philharmonic Theatre, Islington 11 November 1871; Australia: Prince of Wales Theatre, Melbourne 11 September 1873

Very interesting article in anticipation to the Production of this eagerly awaited production of Geneviève de Brabant.

Will we all meet in Montpellier in 2016?

In one of the – all-time – greatest operetta reviews it says, in the “Tribune” about the first New York production 1867:”Mr Grau has distinguished himself by producing at the French Theatre the most revolting mass of filth that has ever shown on the boards of a respectable place of amusement in this city. The new opera is dirty without any excuse or qualification, and the dirt is not gilded with wit, or enriched with sensuous charms; it is merely brutal – the sickening horror of the bagnio […]. Out upon the insolence which offers such beastly exhibitions to a decent community! Shame upon the spectators who can tolerate such an insult to their good fame! Geneviève is not merely indecent, but is grovels in a low depth, even below decency. No lady can look at it without sacrificing her reputation, and no respectable person can look at it at all without feeling degraded by the spectacle.” No wonder the production sold out immediately. And truth be told: THAT’s how I would like to see Genevieve today!

The ‘Gendarmes Duet’ is famous for having seventeen – yes 17 – encores at the first London performance; yet performance yet productions and recordings of this hilarious operetta remain few.

I seek the French libretto for Offenbach’s two gendarmes

Very good work, thank you. I have just bought a photo Nadar, showing Mlle Thérese as Briscote, in 1875.