Kurt Gänzl

The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre

1 January, 2001

Orphée aux enfers was Offenbach’s first venture into mounting a full-scale opéra-bouffe at his blossoming little Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, where it marked a significant advance on the three-, four- and five-handed short pieces which, because of legal restrictions on the size and kind of entertainments allowable under his licence, had been the house’s diet since its inception. The idea of a burlesque of the Orpheus legend, particularly familiar to theatregoers of the time as the subject of Glück’s revered opera, Orfeo [ed Eurydice], had been nurtured some time in the brains of librettists Crémieux and Halévy, but whilst Offenbach was forced to work inside a format which allowed him a maximum of four or five characters, there was little chance of producing a piece which aspired to show Olympus and its inhabitants in all their parodied glory. The dissolution of the prohibitive restrictions in 1858 allowed the collaborators finally to go to work on their Orphée, although Halévy, now making advances in the diplomatic world, decided against allowing his name to go on the credits. By October Orphée aux enfers was on the stage.

Famed courtesan Cora Pearl as Cupid in the “Orphée” revival, Paris 1867.

Orpheus (Tayau) is a boring Theban music-teacher with an eye for a nymph, and his flirtatious wife, Eurydice (Lise Tautin), in her turn, makes sheep’s eyes at the handsome shepherd Aristaeus (Léonce). What Eurydice doesn’t know, however, is that her new boyfriend is no less than Pluto, the King of the Underworld, in earthly disguise. He wants to have her around more permanently, so he fixes it that she treads on a nasty asp in a cornfield and, having duly mortally expired, is consigned to a comfy boudoir in his nether regions. Orpheus is rid of Eurydice, Pluto has her, and everyone would now be quite happy, were it not for that nosy, hectoring creature called Public Opinion (Marguerite Macé-Montrouge). She bullies the unwilling Orpheus into going up to see Jupiter (Desiré) on Olympus, to demand the return of his stolen wife. As a result, the Olympian deities, all thrilled at the thought of a bit of subterranean slumming, descend to Hades en masse and there Jupiter winkles out the hiding place of Eurydice. Enchanted by her, he proposes that she swap Hades for Olympus. But there is still Orpheus to account to and, worse, the dreadful Public Opinion, who seems to have the silly musician mesmerized. When she gets the traditional story back on its rails, and forces Pluto to make Eurydice follow Orpheus back to earth, Jupiter uses a little thunderbolt to make the musician follow mythology, look back, and lose forever the wife he is longing to lose forever. But that is where mythology must stop. For, if he can’t have Eurydice himself, Jupiter is not going to leave her with Pluto and so, in defiance of the classics and of Glück, he turns her into a Bacchante. A highly suitable ending for the girl.

The music with which the composer illustrated this bouquet of comical and satirical fireworks was the most dazzling display of light, comic theatre music in the history of the genre.

From the earliest moments of the score, with Eurydice mooning over her shepherd, or screeching insults at her husband’s music-making, from Aristaeus’ mocking entry song, and the lady’s melodramatic parody of an operatic death (`La mort m’apparaît souriante’) the score bounced along on a bubble of laughter and melody. The Olympian scene introduced Diana with some fleet-footed hunting couplets, and a trio of godly offspring chiding their father over his amorous adventures (Rondeau des Transformations) as well as a quote from Glück’s most famous Orpheic moment, the aria `Che faro senza Eurydice?’, in Orpheus’ unwilling exposure of his case before Jupiter. Hades helped pile up the total of memorable moments with a solo for the lugubrious comic Bache as the dead King of Boeotia (`Quand j’étais roi de Béotie’), Jupiter’s attempts to seduce Eurydice whilst disguised as a fly (`Il me semble que sur mon épaule’) and the famous galop infernale which was to come to be known as `the can-can’.

The show was quickly a major hit (although Offenbach apparently continued well after the opening to operate cuts and rewrites) and by the time it was removed in the following June it had run for no fewer than 228 nights, and its music was being played throughout the country and even beyond. The first production of the show outside France seems to have been at Breslau (ad L Kalisch) in November 1859 before Prague and then Vienna took the show up. Johann Nestroy, at that time in charge of the Carltheater and already the producer of Vienna’s early versions of the short Offenbach works, produced the first Vienna Orpheus in der Unterwelt in his own adaptation with himself playing Jupiter, equipped with enough extra satirical dialogue to make his rôle into something like a meneur de revue. Karl Treumann was Pluto, Philipp Grobecker played Orpheus, Therese Schäfer was Eurydice, Anna Grobecker Public Opinion and Wilhelm Knaack a memorable Styx. Orpheus was a distinct hit and it was brought back at the Carltheater again the following year, by which time Berlin and New York’s German-speaking theatre had also welcomed Nestroy’s version with equally happy results. In Berlin, the piece was popular enough to provoke a burlesque of its burlesque — Orpheus in der Oberwelt — produced at Meysels Theater. In the meantime, Orphée aux enfers had also continued its cavalcade around Paris where, on one famous occasion (1867), the celebrated courtesan Cora Pearl (in her earlier life a London music-hall singer called Louie Crouch) appeared as Cupid.

Gustave Doré’s vision of the „Galop infernal“, as seen 1858 in Paris.

Many other centres soon had their versions — more or less faithful — of Orphée, amongst them Stockholm, Brussels, Copenhagen, Warsaw and St Petersburg, but some places took longer than others to take up this novel kind of entertainment. Although Orpheus in der Unterwelt was played in German at several Budapest theatres and in Hungarian at Kassa (ad Endre Latabár) in 1862, the show was not played in the vernacular in Budapest until 1882. When it was (ad Lajos Evva) it was produced with a starry cast toplining Ilka Pálmay (Eurydice), Elek Solymossy (Jupiter), János Kápolnai (Orpheus), Pál Vidor (Pluto), Vidor Kassai (Styx) and Mariska Komáromi (Cupid), scored a grand success, and quickly began to make up for lost time with revivals in 1885, 1889 and 1895.

In England, although the Orphée score was swiftly and thoroughly plundered to supply music for burlesque scores, it was not until seven years had gone by, and the Oxford Music Hall had scored a triumph with a potted Orphée that J B Buckstone produced a (rhymed couplet!) English version, Orpheus in the Haymarket, churned out by the old master of extravaganza J R Planché at the Haymarket Theatre with a cast including Louise Keeley (Eurydice), William Farren (Jupiter) and David Fisher (Orpheus).

Well enough received, this stiff-necked version was by no means the sensation that might have been expected and played out a slightly shorter-than-intended season before getting the odd brief reprise in the provinces and colonies. The provinces, in fact, put out a much more interesting version four years later when H C Cooper’s travelling opera troupe mounted a more faithful and free-toned version by Arthur Baildon (Theatre Royal, Bath 8 January 1870) with Ledril Ryse (Pluto), Annie Tonnellier (Eurydice), Francis Gaynar (Orpheus) and Henry Lewens (Jupiter) in the leading rôles. The provinces of Britain thus got a better introduction to Orphée than London had done.

Bits of Offenbach’s score got a second metropolitan showing at the Strand burlesque house where an Orphean burlesque was produced in 1871 as Eurydice with Harry Paulton as Aristaeus and most of it at the Royal Surrey Gardens in 1873 when another adaptation of the piece, Eurydice (ad William F Vandervell), was given a hearing for more than 50 nights before going on to be seen at the National Theatre, Holborn in November.

Later, after Hortense Schneider had played two London seasons with Orphée in her repertoire, and after Offenbach’s subsequent full-sized works had made a more considerable mark, it was brought back again in two further English versions.

Hortense Schneider en „folie“, portrait by Alexis Pérignon.

One, produced by Kate Santley (Royalty Theatre, December 1876), starred its manageress as a Eurydice who expanded her rôle with a few cockney music-hall songs, alongside the more conventional Pluto of Henry Hallam and the Jupiter of J D Stoyle, a second, a few months later (ad H S Leigh) was a spectacular mounting at the Alhambra (30 April 1877) in a version this time advertised as `altered by the composer’ (ie Offenbach’s extended rewrite of 1874). Kate Munroe/Cornélie d’Anka (Eurydice), W H Woodfield (Pluto) and Harry Paulton (Jupiter) starred with the rising J H Ryley as Mercury and a `grand procession of 300′ and several ballets interpolated. The piece ran almost four months and was one of the Alhambra’s most successful productions to date.

Australian managers waited even longer to pick up the show, although Offenbach’s score was heard there almost in toto played in Pringle’s and Cellier’s concerts but, when Orpheus did finally appear on stage in the `underworld’, two different productions were mounted within 48 hours of each other. William S Lyster produced Planché’s version in Melbourne with top vocalists Alice May (Eurydice), Armes Beaumont (Pluto) and Georgina Hodson (Public Opinion) and with Richard Stewart as Jupiter, whilst two nights later the burlesque actress Lydia Howard presented her production of the same adaptation at Sydney’s Royal Victoria Theatre, herself playing Eurydice to the Pluto of J J Welsh and the Jupiter of W Andrews in repertoire with two contrasting pasticcio British burlesques, Byron’s Fra Diavolo and [The Nymph of the] Lurleyburg.

New York, though initially quicker to see the show than Britain — several times in German and then at both the Theatre Français and from Lucille Tostée’s company in the original French — took a very long time to get a vernacular production. Both the Kelly and Leon minstrels (2 November 1868, with Kelly as Jupiter and Leon as Eurydice with‘the entire music’) and Bryant’s minstrels (Red Hot by John Brougham, 5 April 1869) came out with burlesques during the Tostée season, but it was not until 1883 that something like a real Orphée was finally given a Broadway presentation in English. It was a decidedly hacked-up version (ad Max Freeman, Sydney Rosenfeld), filled with low comedy, German jokes and local topical songs, produced by E E Rice at the Bijou Theater, and the cast for the occasion included Digby Bell (Jupiter), Marie Vanoni (Eurydice), Pauline Hall (Venus) and D’Oyly Carte contralto Augusta Roche (Public Opinion). This Englished Orphée was, however, far from the first to have been seen in America. As early as 1869 the adventurous singer-manager George Holman himself translated and mounted the show at Toronto’s Lyceum Theater (15 October) with his daughter Sallie as Eurydice to the Jupiter of the not yet famous W H Crane, the Orpheus of the then barely known Charles Drew and the Pluto of George Barton. The piece was played thereafter in the Holman troupe’s long and many tours throughout America. As in Britain, the tour circuits were better served than the metropolis.

In 1874, when Offenbach had launched himself on a new period as a theatrical manager, this time at the Théâtre de la Gaîté, he decided to mount a new production of Orphée.

To fit it for this considerably larger stage, he remade the show, making it both more spectacular (chorus of 120, orchestra of 60, ballet of 60) but also longer and much more full of `items’. The new Orphée stretched to four acts and included a considerable amount of new vocal material, both solo and choral, let in to the script like so many undone pleats. Eurydice (Marie Cico, who had been the original Minerva) and Pluton (Montaubry) each got an extra song, and Mercury (Grivot), Mars and Cupid all got solos to add to what virtually became a divine variety show on Olympus.

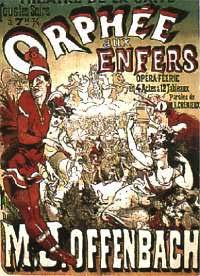

Poster for the revised 1874 version of “Orpheus”.

The were now four ballets, a children’s choir, and an interpolated violin piece played by a young Conservatoire pupil. The final act was extended with a piece for the Judges of the Underworld and a comical policemen’s chorus, a ten-tableaux visit to ‘The Kingdom of Neptune’ including ‘Toads and Chinese fish, prawns and shrimps, a march of the Tritons, a sea-horses’ polka, a pas de trois by seaweed, and a pas de quatre by Flowers (?!) and flying fish’. Christian was seen as Jupiter, and Alexandre was John Styx. If the alterations did little for Orphée as a work (the piece has mostly since been played in its original rather than its expanded version) they served their purpose in giving a `second edition’ to the Paris public, who came to the Gaîté in their enthusiastic numbers, giving Offenbach a success (d’éstime at least — the vastly expensive production actually lost almost its whole investment in spite of taking a huge 811,436 francs in its first hundred performances) which encouraged him to mete out the same bullfrog treatment to several other of his early works for the same stage. The expanded Orphée was, however, brought out at the Gaïté again in 1878 (August) with Hervé in the rôle of Jupiter, Mme Peschard as Eurydice and Léonce in his original rôle, and again in 1887 (19 February) with Vauthier (Jupiter), Jeanne Granier (Eurydice), Alexandre (Pluton) and Tauffenberger (Orphée) featured. This last revival disappointed and was quickly replaced by a re-run of Le Petit Duc.

Expanded Orphées, potted Orphées — and in Amsterdam in 1865 an Orphée where one greedy actor annexed to himself the rôles of Pluto, Orpheus, Jupiter and Styx — but it is, by and large, the original Orphée aux enfers that has survived — with intermittent fallow periods — in the international repertoire through all the changes in musical theatre tastes of the past 140 years.

It has moved from the commercial theatre into the subsidized theatre, and more specifically the opera houses of the world, as one of the handful of classic musical pieces which are repeatedly reprised, taking precedence virtually everywhere even over those later Offenbach pieces which, originally, had a notably greater popularity in various countries: Die schöne Helena in Austria and Hungary, Geneviève de Brabant in Britain, La Grande-Duchesse in America. In Germany, however, it has from the start been the favourite Offenbach work.

Orphée was regularly revived in France until it reached first the Opéra-Comique and then the Paris Opéra itself (19 January 1988) and, amongst countless other productions, was given a large and glitzy German revival under Max Reinhardt at the Grosses Schauspielhaus in 1922. It was produced again in London in a fiddled-with version by Berboohm Tree and Alfred Noyes, in 1911 (20 December), under the title Orpheus in the Underground with bits of spare Offenbach tacked into the score and with Courtice Pounds (Orpheus), Lottie Venne (Mrs Grundy ie Public Opinion) and Lionel Mackinder (Pluto) at the head of the cast, but got a major boost in 1960 through Wendy Toye’s production of Geoffrey Dunn’s hilarious if unsatirical new translation for the Sadler’s Wells Opera. That company’s successor, English National Opera, did very much less well when (5 September 1985) they attempted a rather incoherent and gimmicky staging of the expanded version (ad Snoo Wilson).

Orphée aux enfers has been filmed for television in Britain (including the memorable Sadler’s Wells production of 1962), Germany and Japan.

Austria: Carltheater Orpheus in der Unterwelt 17 March 1860; Germany: Breslau 17 November 1859, Friedrich-Wilhelmstädtisches Theater Orpheus in der Hölle 23 June 1860; USA: Stadttheater (Ger) March 1861, Théâtre Français (Fr) 17 January 1867, Bijou Theater Orpheus in the Underworld 1 December 1883; Hungary: Kassa (Hung) 16 March 1862, Budai Színkör (Ger) 6 May 1862, Népszinház, Budapest Orfeuz al alvilágban (or Orfeuz a pokolban) 12 May 1882; UK: Haymarket Theatre Orpheus in the Haymarket 26 December 1865; Australia: Princess Theatre, Melbourne 30 March 1872;

Videofilms: Sadlers Wells 1962, German TV 1968, East German TV 1974, Brent-Walker 1983, HDTV (Japan) 1990