Richard C. Norton

Operetta Research Center

30 March, 2015

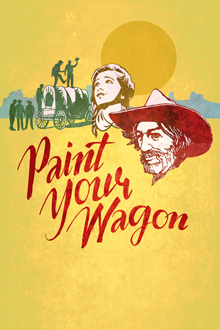

Alan Jay Lerner & Frederick Loewe’s Paint Your Wagon (1951) is seldom produced these days, and Encores’ one-week staged concert presentation at New York’s City Center proved a joyous revelation in ways both good and bad. The glory of this show was in hearing its score complete with its original orchestrations, and hearing the voices of its principals and the 16 baritone male chorus, and especially Alexandra Socha and Justin Guarini as the lovers Jennifer and Julio.

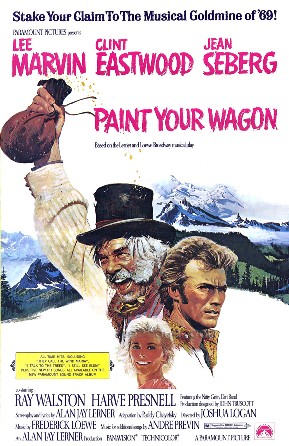

Poster for the 1969 film version of “Paint Your Wagon.”

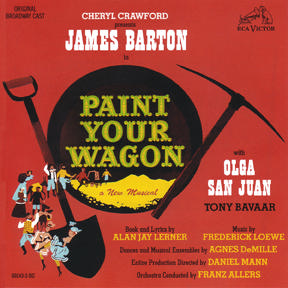

Most theatergoers know the score from its RCA Victor original cast album, typical in LP length for its day, but omitting the Mormons’ comic Trio, The Strike, overture, entr’acte, finale, much dance music and reprises. Or else the much reviled 1969 film which told a different story, and gutted Loewe’s score with mediocre interpolations by Andre Previn. In short, Paint Your Wagon is just the show that Encores! should be reviving. The rousing welcome it received from audiences and press alike has prompted plans for an all-new recording from Encores, and news that a revised book from playwright John Marans will be used for a forthcoming stage revival in Seattle.

While one cannot make the claim that Paint Your Wagon’s score yielded as many classics as L&L’s My Fair Lady, Camelot, Gigi and Brigadoon, three enduring standards have lasted: Julio’s rhythmic ballad “I Talk to the Trees,” the driving male chorus “They Call the Wind Maria” and Ben Rumson’s philosophy of life “Wanderin’ Star.”

As librettist Lerner conceived an original story based on America’s gold rush in the 1850s, its unabashed free-market optimism and greed in Act 1, tempered by reality as the rush dwindled to a trickle in Act 2. Crusty old Ben Rumson’s discovery of gold in the opening scene spawns the over-grown town of Rumson Creek. As a widower, Rumson attempts to raise his 16-year-old daughter Jennifer in a town of 400+ men and no women, resulting in predictable friction. Once Jennifer falls for the Mexican miner Julio, and Ben Rumson acquires a second wife, Rumson sends his daughter east to get a proper education. As Rumson Creek collapses a year later, Jennifer and Julio are reunited by final curtain.

Composer Frederick Loewe. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Berlin-born composer Fredrick Loewe surprises us with his ability to evoke a distinctly American sound of the wild west, its rugged, male-dominant culture. Few musicals are set there, Annie Get Your Gun, Seven Brides For Seven Brothers, Destry Rides Again and Crazy For You spring to mind. But Lerner’s story of dreams betrayed, hopes dashed, compromises made, correlate thematically with his later work on Camelot, and Paint Your Wagon is a fundamentally more serious work than these other Westerns. Less well-known songs in the score are Jennifer and Julio’s tender duet “Cariño Mio,” and Jennifer’s plucky “What’s Goin’ On Here?,” “How Can I Wait?,” and “All for Him.” As Rumson Creek deflates in early Act 2, Julio shares the wistful “Another Autumn” with fellow miner Steve Bullnack. The male ensemble numbers, apart from the smash “They Call the Wind Maria” and the upbeat opener “I’m On My Way,” tend towards the generic, with “Hand Me Down That Can o’ Beans,” “There’s a Coach Comin’ In,” “Movin’, “The Strike” and Ben Rumson’s wedding celebration “Whoop-Ti-Ay.” One welcome surprise is the comic “Trio” for three minor characters, Joshua Wooding and his two bickering wives. It is odd that the stirring “They Call the Wind Maria” is assigned to Steve Bullnack, whose character has scant dramatic function. In this capacity Nathaniel Hackmann seized the opportunity to steal the show and advance his career.

I’ve neglected to mention Ben Rumson’s wistful recollection of his late wife, “I Still See Elisa,” perhaps because Keith Carradine’s sentimental rendition was little more than adequate. Just minutes after his hymn to Elisa, he’s angling to buy himself a wife he’s only just seen for the first the first time.

LP cover of the Original Cast album of “Paint Your Wagon,” 1951.

The real problem with the evening is Alan Jay Lerner’s problematic book. It offers not so much a plot but a situation or setting ripe with possibility, but in which nothing really happens. What does happen occurs mostly off-stage, un-seen. Act 1 unfolds a few unrelated incidents (discovery of gold in opening scene; the arrival of Mormons; a stagecoach full of can-can dancers arrives for the finale). Act 2 simply recounts the slow decline of the town Rumson Creek in sad, predictable, sorry detail. Apart from some casual observations about the smallness of man vs. nature, and the hardscrabble life of a miner, Lerner has neglected to write us a compelling story. The inevitable reconciliation of Jennifer and Julio is delayed until the end. If Lerner’s rivals Rodgers & Hammerstein used songs to advance the plot so effectively in Oklahoma, Carousel, South Pacific and The King and I, L&L have regressed from what they did so well in The Day Before Spring and Brigadoon. L&L use songs in PYW to comment upon the plot or else create a mood, which leaves the show oddly languorous and diffuse, punctuated by inconsequential dialogue, virile posturing and lame jokes.

What passes for humor is an odd misogyny (women are either chattel, objects of desperate lust, or baby machines) which bluntness Lerner finds historically significant, perhaps comic or quaint for 1951.

Poster for the 2015 production of “Paint Your Wagon” at New York City Center.

Today such jokes play either tasteless or else stupid. Despite Marc Acito’s shrewd editing of Lerner’s text and its superior 1952 revision, he’s not permitted any structural changes. Ben Rumson is much the same man at the start and end, plus or minus gold, or a wife, still wanderin’. Only his daughter Jennifer Rumson experiences any sort of real change in the show (offstage between Acts 1 and 2). Her lover Julio’s romanticism is tempered by hardship. The potential for exploring Julio’s role as a racial, cultural outsider/outlier is inexplicably ignored, if you compare it to the explicitness of race in The King And I and South Pacific. Or think even of the comic role of the Persian Ali Hakim in Oklahoma!, or the tragedies of Jud in Oklahoma! and Billy Bigelow or even Jigger in Carousel. If Julio is the only Mexican in Rumson Creek, and he’s finding romance (or sex) when none of the other men do, the potential for conflict, drama or violence with his rivals is great. Instead of Jennifer’s bandaging his foot from an injury, it might be more effective if he had been beaten by his fellow/rival miners. Sad to say, despite the exceptional talents/efforts of Justin Guarini in this revival, Julio as written is scarcely more than a postcard romantic juvenile.

Director Marc Bruni plays to the strengths of the musical score; the virile dances by Denis Jones, remarkable for a short rehearsal period, are a welcome respite from the tedious story. But too often they amount to much ado about nothing. Surely Agnes de Mille must have found something more to say in dance in 1951. Listeners to this glorious score as conducted by Rob Berman on the forthcoming CD may need not know what they are missing in a story.