Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

28 October, 2018

Recently, a review of a new Land des Lächelns production by Guy Montavon at Oper Wuppertal sparked a debate about ‘racism’ in operetta when critic Stefan Keim claimed, on German national radio Deutschlandfunk Kultur, that the representation of the Chinese in this production was unacceptable. And that the show itself was equally unacceptable: “Especially in our current situation [of refugee problems] the message of the show is incredibly problematic. It says to the audience ‘Don’t start an affair with a foreigner, it’ll lead to disaster. It’s just as problematic to see a staging that has nothing to say about this.” Critic Stefan Keim claims the libretto should have been re-written – completely! – before being brought back to the stage in Wuppertal. A request that Wuppertal’s intendant Berthold Schneider says no to, just as he denies that there is any ‘racism’ on display in the Montavon production, because all characters (Austrians included) are portrayed as ridiculous. So who’s right?

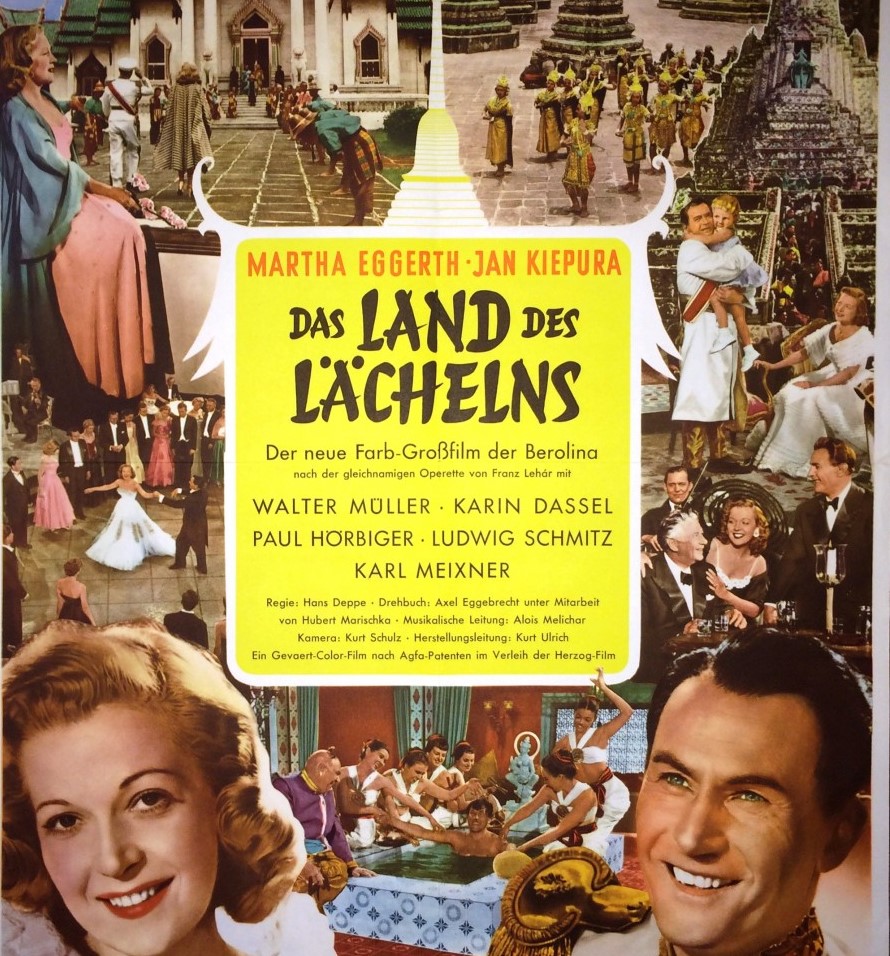

The 1952 film version of “Land des Lächelns” with Marta Eggerth and Jan Kiepura.

It’s a double debate, really, maybe even a triple one: (1) is the 1929 show itself racist in the way that the authors Fritz Löhner-Beda and Ludwig Herzer portray China and the Chinese as laughing stock characters? (2) is a modern production racist that doesn’t mark such ‘racist’ stereotypes and find a critical contemporary way of handling them? (3) why do German operetta critics feel obliged to raise the racism question while Austrian critics reviewing the much lauded new production at the Lehár Festival in Ischl this summer could not be bothered to even mention that putting Chinese characters on stage, played by white Austrian actors in yellow face, as ridiculous stock figures might be seen by some as unacceptable and offensive? There are no simple answers here. Which is why the ‘racism’ debate is so necessary and worthwhile, also in operetta land whose inhabitants, for the longest time, behaved as if all the hot topics being fiercely battled over elsewhere have nothing to do with them. (Yeah, dream on.)

Thomas Blondelle and Alexandra Reinprecht in “Land des Lächelns” at Ischl’s Lehár Festival, 2018. (Photo: www.fotohofer.at)

As one user wrote on the Operetta Research Center Facebook site, in reply to the Wuppertal story: “Typical first world problems: If you can’t find real problems, create new ones.” Another commentator added: “Land des Lächeln is an operetta from the 1920s with wonderful music, it tells the story of two people in love from different countries. To listen to this music and the singers is enough for me. Why [must somebody] always cry out and shout this is racism today [?]. This is a fairy tale and not reality.” She went on saying: “If I want a debate about the ugly realities of today I don’t go to an operetta, I know reality; I don’t need it in a staging like this. All this changing of texts and stories in the operetta world for something grey and modern … Isn’t that what’s nice about operetta: the gorgeous music, the fairy tales, and the colorful images? They are all part of the magic. I want to enjoy these things, get away from everyday life for a few hours. That’s why I go to an operetta performance. […] Why does this magic have to be destroyed? Don’t people have better things to do?”

Verena Barth-Jurca as Mi in “Land des Lächelns” in Ischl, 2018. (Photo: www.fotohofer.at)

If we followed that definition of operetta – ‘fairy tales with gorgeous music’ – we’d keep the genre as detached from life and as intellectually uninteresting as it has presented itself in post-World War 2 years: a ‘safe space’ for people who didn’t want to encounter problems or triggers after the horrors of war, a pain killer for the weary and tired who were exhausted from the challenges of rebuilding a life after the collapse of the Nazi regime and destruction of so many cities in central Europe. For those operetta fans the verdict of Austrian journalist Bertram K. Steiner applies. He wrote as late as 1997: “One arrives at operetta as a veteran of existentialism, after one has realized that progress and regression lead to the same inferno. For radicals and bigots of all coloring, for immoral optimists, operetta is a horror, of course. They will learn soon enough how idiotically soothing it is to be wedded by the little finch (Dompfaff) and afterwards do as the swallows do.”

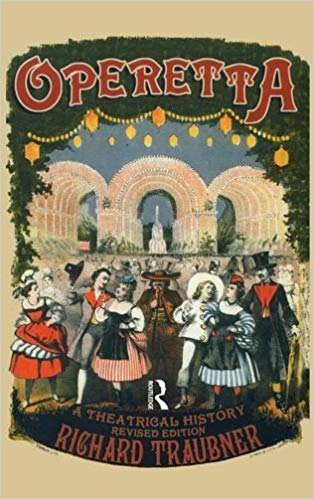

Richard Traubner’s “Operetta: A Theatrical History.”

I’d like to propose that it’s time to overcome such a definition of operetta. Which goes hand in hand with Richard Traubner’s definition that operetta is “flowing champagne, ceaseless waltzing, risqué couplets, Graustarkian uniforms and glittering ballgowns, romancing and dancing!” The late Mr. Traubner added in his book Operetta: A Theatrical History, in the updated edition of 2003: “[Operetta is all about] gaiety and lightheartness, sentiment and Schmalz.” Maybe the Wuppertal racism ‘scandal’ is as good an opportunity as any for reconsidering such definitions and the fairy tale approach to operetta. (After all, even Disney’s fairy tales address central problems of today’s society, clearly visible under all the costuming.)

Sheet music cover for Offenbach’s “Ba-Ta-Clan.”

The art form operetta has used and has made fun of ethnic groups and minorities from the very beginning. Think of Offenbach’s Ba-ta-clan with regard to the Chinese (who turn out to be French), or the Peruvians in La Périchole. Or the ridiculously pompous Balkan characters in The Merry Widow. In his book Anything Goes: A History of American Musical Theatre, Ethan Mordden writes about “The Age of Burlesque” and operettas of the 1870s to 1880s: “The [American] musical in general was to stereotype Europeans as stock figures – especially as immigrant in America – playing on their accents and malapropisms for humor. In Evangeline’s day they were Scandinavians and Germans. (‘Dutch’ is simply a corruption of deutsch.) Later, Irish, Italian, black, and Jewish stereotypes emerged. Although the intention was to create fun at a minority group’s expense, the long-range effect was, paradoxically, to socialize and assimilate alien peoples through familiarity. Stereotyping precedes sensitive portrayal which engenders equality and a share of political power.”

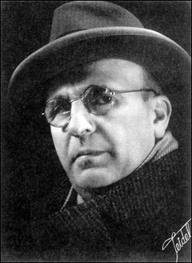

Star librettist Fritz Löhner-Beda.

One key element in early operetta was that ‘the others’ – i.e. the ethnic stock characters, the sexual minorities, the social outcasts, the women behaving in non-normative ways, the nance characters – were ridiculed just as badly as everyone else. This equal share approach got somewhat lost in later operetta history; it certainly does not fully apply to Land des Lächelns. Still, that Lehar show tells a fascinating culture clash story with two fascinating central characters fully worthwhile exploring again and again, also today, not just because of the gorgeous music. The librettists were Jewish outsiders in an anti-Semitic Austrian society and they knew only too well what it felt like to be ridiculed and excluded; much of their own experience went into their writing and the way they portrayed ‘otherness’ in their operettas, often in a highly self-ironic way. Finding such irony and references about what it means to be an outsider in the text of Land des Lächelns (and many other operettas of the era) would be rewarding, instead of burying such layers under the thick coat of ‘existentialist’ fairy tale colors that blind operetta goers and take away some of the basic ingredients of the genre’s original success and relevance.

A 2015 promotion image by the Metropolitan Opera, advertising a production of Verdi’s “Otello” with Latvian tenor Aleksandrs Antonenko in heavy bronze makeup. (Photo: The Metropolitan Opera, New York.)

But who is allowed to play the Richard Tauber role of Prince Sou Chong in our age of identity politics, when an Otello at the Metropolitan Opera caused an outcry because a white Latvian singer was shown in shadows and with dark makeup in an advertisement? (Even though the ad was far from anything that might resemble black face.) At the same time, no one protested about Belgian tenor Thomas Blondelle performing Sou Chong in Ischl with yellow make up, not to mention Piotr Beczala in Zurich singing the role with a hint of oriental costuming, but not Asian make up at all.

The double staircase in Andreas Homoki’s “Land des Lächelns” at Zurich Opera, with Piotr Beczala in a yellow costume. (Photo: Toni Suter / Oper Zürich)

Where do we draw the line – and who draws the lines, for that matter? Is operetta too off focus for American anti-racism activists to take note? There was, after all, a production of The Mikado in Seattle that had to be cancelled because of protest about the inappropriate yellow facing, so it’s not as if the debate hasn’t reached the United States and its operetta world. Which might explain why the Ohio Light Opera keeps such a low profile, to not draw too much attention to what it’s doing, lest protesters should start marching up and down in front of the theater in Wooster.

A scene from the original production of “The Beastly Bombing.” (Photo: Kim Gottlieb Walker)

A good example of the resurrection of the equal share of ridicule approach in operetta in The Beastly Bombing: A Terrible Tale of Terrorists Tamed by the Tangles of True Love. With a libretto by Julien Nitzberg and music by Roger Neill (of Mozart in the Jungle fame) it premiered in Los Angeles in 2006. The European premiere took place in Amsterdam in 2009.

The Beastly Bombing has strong South Park elements in it, and it pokes fun at just about everyone imaginable: Jesus, the US President, orthodox Jews, pedophile priests, drug popping teenagers, white supremacists, radical Islamists from Saudi Arabia, gays, Japanese. The list goes on and on. Yet no one group is put above another, everyone is treated as equally laughable – which is how the authors defended themselves against accusations of being anti-Semitic.

Of course the creators of the real South Park, Trey Parker and Matt Stone, presented their own stage musical filled with a staggering amount of ethnic stereotypes with The Book of Mormon in 2011.

In the recent book Freiheit ist keine Metapher: Antisemitismus, Migration, Rassismus, Religionskritik Sana Maani writes: “The Book of Mormon – received enthusiastically by audiences and critics alike – is a biting and sometimes vulgar satire on Mormonism; by comparison the [Parisian] Mohammed caricatures are absolutely harmless. It’s not difficult to imagine that the one or other Mormon might have seen his ‘honor’ violated by the musical, maybe even consider such ‘honor’ lost altogether because of The Book of Mormon. […] The show had the potential to unleash hatred and aggressive energies, leading to terrorist acts.” But this did not happen. Neither were there any protests from black activist groups because of the portrayal of blacks in Uganda – which is where the two Mormon boys in the show are sent. Instead of protests, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints actually placed ads in the Broadway playbill saying: “You’ve seen the show, now read the book!”

Why did critics and activists find The Book of Mormon and its portrayal of Africans and Mormons acceptable, and why was The Beastly Bombing praised in glowing words by The New York Times, and what did these two shows do that (apparently) the Wuppertal production of Land des Lächelns did not do? Shouldn’t the Chinese tourist board also place ads in playbills for Land des Lächelns? Just like the tourist board of St. Wolfgang did for years in playbills for Im weißen Rössl, even though the 1930 Charell/Benatzky show also presents stereotypical Alpine characters that are ridiculed, each and every one of them, including Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph. Could such an approach be applied to Land des Lächelns, making the Austrians in the show just as laughable as the Chinese? Would that make Land des Lächelns less ‘racist’? (As the Wuppertal intendant implied.)

In a feature article for Opera Canada Catherine Kustanczy wrote earlier this year, “Some facets [of operetta] are, to contemporary eyes, quaint at best, and offensive at worst.” She asked Barrie Kosky from Berlin’s Komische Oper about this. “The portrayal of race in certain works presents an impediment that Kosky believes can only be overcome with direct confrontation.” With reference to Gilbert & Sullivan and the racism in their works, Kosky says: “[I]f I was a programmer in England, the first thing I’d do is get a Japanese director and Japanese performers to do The Mikado. People would go, ‘What am I watching here?!’ It would be so fantastic.”

Poster for the 2000 movie “Tears of the Black Tiger.”

Indeed it would be, maybe as fantastic as the 2000 Thai cowboy movie Tears of the Black Tiger. It presents a John Wayne world of action – cast exclusively with Asians in Wild West costumes. It really makes you see this genre with new eyes. Plus, it’s incredibly funny and enjoyable. And: there’s lots of music in it, too!

Getting back to a more equally distributed parody approach – and bringing in people who might look at operetta stories from a very different perspective and cultural background than white male Caucasians do – would greatly benefit operetta; because operetta has been stirring in stale post-war juices for far too long. It’s time for a fresh start and a revolutionary new beginning. That might take us back to the future. Land des Lächelns was, after all, a daring show in 1929, and it was a big commercial success because of this. Not in spite of it. Reason enough to confront it and its themes directly, as Mr. Kosky suggests. And while we’re at it: do the same to all operettas, please. The time for escapist fairy tales with narcotic music should be over, 70 years after World War 2 has ended. Personally, I’d love to see Tears of the Black Tiger director Wisit Sasanatieng stage a Weißes Rössl with an exclusive Asian cast. Or let a Turkish director take on Leo Fall’s Die Rose von Stambul. Or how about Spike Lee staging Kalman’s Golden Dawn set in Africa and overflowing the racial stereotypes that tell us a lot about racial realities on Broadway in 1927, realities that are worth knowing and discussing and showing. As confrontational as possible.

Lobby Card for the movie version of “Golden Dawn”.

If that involves re-writes, then okay: operettas have been re-written forever (Land des Lächelns is, after all, a re-write of Die gelbe Jacke). But I’m sure you could get pretty far with the original texts if you really explored their potential. Doing so might be a little more daring and interesting than the kind of re-writes Stefan Keim talks about on Deutschlandfunk Kultur.

I had this to say about Morbisch’s production of Land des Lachelns in Fanfare 38:4:

All is well in light hearted Act 1, as the dignified Chinese Prince Sou-Chong, envoy to the Austro-Hungarian Imperial Court, meets and falls in love with the young and beautiful Countess Lisa, although Daddy and her would-be boyfriend, Count Gustl, aren’t quite fully convinced. At the conclusion of the act, Sou-Chong is called back to China to become the new head of state, and at the last minute Lisa convinces herself to go with him. It is only when they reach Peking that events turn darker. Countess Lisa is met coldly by the Chinese court. Sou-Chong’s uncle, the head of family, tells the prince he must take four Chinese wives, and it is against Chinese law to marry a white woman (at least the English subtitles put it that way). Lisa must be kept as a concubine if the prince desires to keep her. Sou-Chong says, I am the new ruler, I will change the law, but of course he doesn’t, he obeys his uncle. He also explains to Lisa that in China women have no rights, they are the property of their master. The gentle approach for our boy Sou. Perhaps these onerous customs all existed at one time, but even in those days I doubt if such treatment of a noblewoman who’s put her trust in you would be considered princely behavior anywhere. It is certainly unacceptable to us today. If the original librettist, Victor Leon, was attempting to portray a clash of cultures he certainly succeeded. Poor Lisa finds herself virtually in the same situation as Konstance in Die Entfuhrung and Rossini’s Isabella in L’Italiana in Algeri, a western woman to be kept as a slave to love, not of her own volition. Countess Lisa says, ‘Help! I want out! How can I love a man that treats me like this?’ Fortuitously, Count Gustl has been appointed Chinese Ambassador with Daddy’s help, and aids Lisa’s escape. Although still in love with his countess, Sou-Chong lets her go, singing something about the inscrutable Chinese smiling when their hearts are broken. Audiences today would probably think it only serves the clueless bonehead right.

It seems to me there is more of a problem here than just Chinese or Austrian stereotypes. The oafish and male dominant treatment of women and the lack of any support for a supposed beloved one by a so-called prince are main themes and not very pretty ones from our librettist Leon. This is not just a bit of Austrian puffery tied to some lovely show music, and Land des Lacelns deserves to be called out for its unsavory and probably racist storyline.

Bill White

Right. Only Jews must play FIDDLER. The storyline of OTHELLO must be razed.Pieces such as Victor Herbert’s WIZARD OF THE NILE and Suppés REISE IN AFRIKA be banned. Anything with an oriental or an Arab in it .. don’t eat. Non-Caucasian actors must never be allowed to play roles written for Caucasians. It is an argument of such stupidity that could only exist in an age such as this.

A couple of points for this humourless era. The ‘Japs’ of THE MIKADO were intended to be played by white men being yellow. It is, for goodness’ sake, an opéra-bouffe. A burlesque. And the woman who unilaterally cancelled the Michigan show was censured and the show rescheduled for the following season.I hope she’s gone away and married Kim whatsit the wedding queen.

The libretto for LAND DES LÄCHELNS is perfectly straightforward and professional. If it has a message, it is ‘east is east and west is west’. Of lovers who are torn apart by failing to shuck off the differing traditions of their countries. A perfectly fine (and much used) theme in drama for centuries.

But it is fashionable in certain circles to apply 21st century -isms to work from another era. It will give a generation of striving undergraduates the stuff of theses and doctorates just as other fashions have done ..

Bah! Bunkum! Poppycock!I’m off to listen once more to ROSE OF STAMBOUL and PIRATES OF PENZANCE. Oh no! I can’t. That’s offensive to Major Generals with 15 daughters, the House of Lords, the Police Force .. and of course the role of Mabel was created by a Jewess so MUST not be played by anyone not of the persuasion …

Why am I wasting my breath?

Well, Mr. Ganzl, some of us know a rose is a rose whether it is from Stamboul or any other locale. It is not fake news nor any altered neomodern viewpoint to suggest there is something morally reprehensible in Land des Lachelns libretto. If you cannot see that you must have a blind spot a mile wide. Your other examples in support are inane and just plain silly. To my thinking, you certainly are wasting your breath and our time.