Boris Michael Gruhl

Operetta Research Center

10 September, 2014

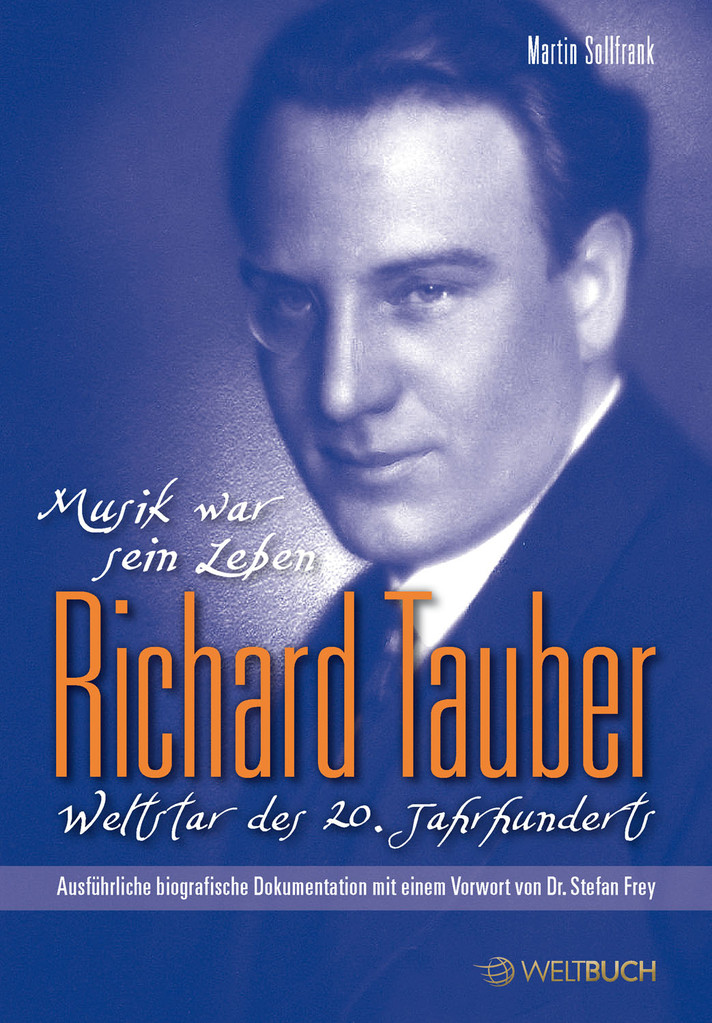

Martin Sollfrank has written an exhaustive, 568 page biographical documentation entitled Musik war sein Leben: Richard Tauber – Weltstar des 20. Jahrhunderts, published by Weltbuch Verlag Dresden. He presented the book at the “Literaturlounge” in the Heinrich-Schütz-Residenz in Dresden last week-end where we caught up with him.

The new Richard Tauber biography by Martin Sollfrank.

“Soldiers have hobbies too, you know. Mine is beautiful voices.” The beautiful voice in question, here, is that of Richard Tauber. And the soldier captivated by it from the moment he first heard it, back in 1972 on an old LP, is Martin Sollfrank. It was a recording of Don Ottavio in Mozart’s Don Giovanni, to be precise, the aria “Il mio tesoro.” It was followed by “Dein ist mein ganzes Herz” from Das Land des Lächelns by Franz Lehár.

From then on, Sollfrank’s Tauber collection grew, first it was LPs, later CDs were added. By the time the digital age arrived, collecting Tauber recordings had turned into something of a serious passion. In addition to listening to music, Sollfrank had also started reading every available biography of this singular singer, born on 16 May, 1891 in Linz, in an inn called “Zum Schwarzen Bären” (The Black Bear”) and died in London on 8 January, 1948.

Sollfrank did not limit himself to listening and reading, though. Soon, the professional soldier and infantry man got suspicious about the facts he found in print, in essays, articles and books.

They were semi-truths, he says, or “biographical fairy tales.” He wanted to know the “real” truth and started researching. He wanted to be as precise as possible about everything in Tauber’s life – how the career of this singer moved forward with equal brilliance and artistic competence in the realm of opera, operetta, Schlager, Lieder and the concert programs.

There are countless recordings to prove this brilliance and competence. Yes, you hear a different stylistic approach, even a slightly different technique, but no matter what Tauber sings – Mozart, Lehár, Lieder by Schubert or Schumann – his goal is always clear: giving his very best in the moment of performing. It is something that is omnipresent on every recording after the first serious scolding Tauber got at the beginning of his career in Dresden. It marked him for life.

The Semperoper seen in a historical bird-eye perpective, around 1900. (Photo: Wikipedia)

On 26 January, 1915, Count Seebach, the general director of the Dresden Opera, complained to a colleague in Chemnitz about Tauber. That colleague was Tauber’s father. Seebach told him about the lacking enthusiasm of the young singer, criticized his notorious “s” problem and said that “he has started to quaver frightfully.” Tauber Senior gave his son a serious bollocking, and Junior promised to better himself.

He certainly did. There are no further known complaints, anywhere.

Nikolaus Graf Seebach, painted by Robert Sterl in 1912. (Photo: Wikipedia)

It was Seebach, by the way, who advised Tauber Jun. to stop wearing metal rimmed glasses, but a monocle instead. “Any tenor of mine is allowed to look vain, but not like a poor clerk from Kötschenbroda.“ (That is a little village near Radebeul in Saxony, near Dresden.)

Forthwith, Tauber’s monocle became something of a signature item.

On 1 August, 1913 Tauber was given the title „Königlich Sächsischer Hofopernsänger,“ i.e. he became a member of the ensemble of the Dresden Court Opera. From then on his career took off, based on incredible devotion to studying, something that is documented at length in Sollfrank’s book. It shows with what attention to detail Tauber learned his musically diverse roles, and how incredibly fast he was able to do it.

At some point he was called “SOS Tauber” because he was able to take on any part overnight and save performances.

That is how he famously came to sing Calaf in Puccini’s Turandot in the first German performance in Dresden, on 4 July 1926. That he could substitute for his sick colleague Carl Taucher was something he heard about in an interval of Die Fledermaus, during a performance at the State Opera Berlin on 2 July. Tauber learned the role in two days and switched genres with the greatest possible ease.

Richard Tauber in a 1920s cigarette ad.

In the course of seven years, Martin Sollfrank amassed documents, worked in archives and libraries, contacted people around the world to get copies of documents.

He says he was able to reconstruct about 95 percent of all Tauber performances. 960 documents come from the historical archive of the Sächsische Staatsoper Dresden. All in all, the book chronicles Tauber’s appearances as opera singer, operetta singer, concert and Lieder singer, passionate interpreter of international folklore, but also of seductive Schlagers. Even the radio programs are included. And most of the 735 Schellack recordings are described too, or at least listed. There is no separate discography, though.

From a modern perspective, it is amazing how well Richard Tauber marketed himself. He was a well-known advertisement figure for razor blades as well as for the cigarette brand “Das hohe C,“ created especially for him by the Dresden tobacco company Salem.

Everything that Martin Sollfrank has put together in this massive book – images and countless documents – and everything he has to say about Tauber refrains from speculation.

We are only being told things about Tauber’s life and career that the author can document. As a result, “a panoramic view on the phenomenon Tauber arises, which we thought impossible to achieve,” writes Lehár biographer and operetta expert Stefan Frey in his preface.

Richard Tauber singing at a charity concert in Berlin in 1932.

After reading this engaging book, the impact of the artist on his historical audience becomes clearer. He did not have “Sitzfleisch,“ i.e. he could not sit still. He had to constantly perform and work, right till the very end, when he was already marked by his illness. The book describes the many aspects of Tauber’s career until his death in 1948, including his career as composer and conductor of own works as well as of works by others, as an artist able to masterly use the media and the new medium radio.

“The portrait of a contradictory personality arises, whose opposing aspects play an important part in understanding the fascination Tauber had for his audience,” write Frey in his preface.

It was Tauber singing Mozart that started his career. Later, meeting Franz Lehár was a crucial turning point for both of them. And even though Tauber met up with Lehár one last time after the Second World War, to give an unforgettable radio concert in Switzerland, it was Mozart’s music that ended Tauber’s career. Tamino in the Magic Flute had been his very first appearance in Chemnitz on 28 September, 1913; as Don Ottavio he performed at Covent Garden for the last time on 27 September 1947, in a guest production of the Vienna State Opera where he had sung – back in 1934 – Lehár’s last operetta, Giuditta.

A splendid article, thank you so much!