Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

7 May, 2018

This spring, stage director Felix Seiler and choreographer Danny Costello staged Paul Abraham’s Die Blume von Hawaii with students in Osnabrück. Stuttgart born Mr. Seiler has worked for many years as assistant to Barrie Kosky, including for his Ball im Savoy production at Komische Oper Berlin. Danny Costello – from the Rocky Mountains – has worked for years as a musical comedy performer, e.g. at Theater des Westens in Berlin. In 2008 he left the stage and focused on a full-time choreographer career with Funny Girl, Crazy for You and Street Scene among his credits. One of Mr. Costello’s most famous operetta works has been Nico Dostal’s Clivia with Geschwister Pfister in Berlin. We spoke with both gentlemen about their close encounter with a 1931 jazz operetta in Osnabrück. How did they – and how did young musical comedy students – react to such a historic show that has been bad mouthed by many operetta experts in the not too distant past?

Stage director Felix Seiler. (Photo: Private)

You just staged Paul Abraham’s Die Blume von Hawaii with young students: how did they react to operetta music that many people (of their generation) consider old-fashioned and out-of-date?

Felix Seiler: In the very beginning there might have been a bit of disappointment when they learned that the stage production (which would be the highlight at the end of their studies) was not a musical, but rather an operetta – considering their whole line of study focuses on learning how to perform musical comedy. However, once they got involved with their roles, read the dialogue, and, most importantly, studied and listened to the music, I didn’t have to do much to sell the show to them. Paul Abraham’s music, its colors, its rhythm, and the catchiness of the tunes (every number is such a distinctive Ohrwurm!), worked the magic itself. And since jazz is still very popular amongst younger generations, I imagine the jazz element worked for the students as a clever hook-up to the mostly unknown world of operetta. It’s remarkable when you think that bringing jazz to operetta back in the 20’s and 30’s had its origin in the idea of saving operetta as a genre – and that almost 100 years later the combination is still attracting new audiences and new performers.

Danny Costello: When I entered the picture, Felix had already been working with the students for a good two weeks, and as far as I could see, each and every one of them was fully committed to their roles at that point. Having already done both scene work and music rehearsal, they had surely seen as much beauty and abundance within the Abraham material as they would have in any modern-day musical (if not much more!), and they will surely have known that Die Blume von Hawaii would give them the exciting opportunity to use 100 percent of their talents, and to grow as young performers. As Felix said, the show sold itself!

The students of the Hochschule für Musik in Osnabrück rehearsing “Die Blume von Hawaii.” (Photo: Private)

Why did you – or the Hochschule in Osnabrück – decide to perform this particular show, and not something else? Why did you want to stage this escapist exoticism that’s been criticized by many as a “degeration of operetta,” especially Volker Klotz in his famous Operette: Porträt und Handbuch einer unerhörten Kunst (1991)?

Seiler: After already having done one production with the musical students in Osnabrück in 2015, the Hochschule was very generous in offering me this project, insisting that I could pick anything I want – “even operetta”, they said. Although I’m a big fan of musicals of all kind, when it comes to the staging, the style of characters, the (often) terrible German translations, and, from my perspective as a director, the quite narrow path of what you’re allowed and not allowed to do with the piece, I thought it would be a wasted opportunity not to take the students in the direction of something they’d never done before – especially when the chances are quite high they will soon be confronted with it in their working lives! From working as an assistant director at the Komische Oper in Berlin for several years, I knew what fabulous material there is, just waiting to be worked on, once you open yourself up to operetta. So, when I came across Die Blume von Hawaii it was not only the Abraham music where every bar is so rich with vibrating atmosphere that it immediately got me interested, but the brilliance, humor, and pace of the dialogue, alongside a wonderfully mixed bunch of crazy, loveable characters. I think criticizing the piece for its “escapist exoticism” is falling short, because it totally ignores the fact that the piece is absolutely aware of it, and that there is a very fine and charming irony in the opportunity to break the excapism at any given moment. One of the big laughs that landed in every performance was the moment at the end of the show, when Bessie, with full seriousness, states: “Everybody is here in Monte Carlo! It almost feels like the third act of an operetta.”

What were the greatest obstacles or problems for the students in adapting to the required Abraham style?

Seiler: I think one of the most difficult obstacles facing them could be found in the more dramatic/serious numbers, where it initially seems like the music is all the same, but where, in actuality, every verse and every refrain, each ritardando, each pause needs an individual approach. Only at that point do the vitality and the irresistible dramatic power and ecstasy, all qualities of Abraham, begin. Another challenge were the numbers that have to be performed presentationally, as numbers within the show (such as “Wir singen zur Jazzband” or “Heut’ hab ich ein Schwipserl”). For these, the students needed time to find that special awareness of what it means to perform in front of two audiences, while not neglecting either of them – the one on stage, or the one in the auditorium. One thing, which might have been more of a learning process about operetta in general, was the task of delivering lyrics and language that sound kitschy, funny, or sometimes ridiculous, while maintaining that special tone, which I mentioned before, of being serious about them – and in addition, having a twinkle in the eye now and then.

Choreographer Danny Costello. (Photo: Private)

Costello: I think Felix made an excellent choice when he chose a project written so long ago. It gave the students, most probably, their greatest obstacle, but also, their most rewarding learning experience. It was fascinating to watch them deal with the tempo of certain dialogue (which is the key to its success). Today, in their everyday life, they would never speak in such a stylized manner, but in their struggle to learn the rhythm of stylized dialogue, they were able to learn a great deal about comic timing and delivering material effectively (and listening!). In terms of Abraham’s music, it embodies the period so completely (as well as those wonderful ethnic flavors of Hawaii!), that it was a similarly unfamiliar challenge for the students when it came to mastering the musicality of that particular age, or learning what must have been, for them, truly unusual dance movement associated with that era (and, of course, exotic Hawaii).

Blume von Hawaii was – originally – about dancing and overwhelming ritual ceremonies on stage, for the coronation of Laya in act 2. (Some of it can still be seen in the 1933 movie.) How important is dancing/choreography in operetta productions today, as compared to the last few decades? What requirements are there for operetta performers?

Costello: I wouldn’t want to claim here, by any stretch of the imagination, that I am an expert on operetta. I am a choreographer of musical theater who happens to have the great good luck of being associated with, and being allowed to work with, several lovers of operetta. My approach to all movement within the structure of any piece is to find the common ground between the music (!), the vision of the director, the given talents of the performers, and (sadly) the restrictions of the budget. I can imagine that many operettas are performed with very little choreographed movement, as the emphasis will always be on a perfect marriage of story and music. To many, that will be enough. However, there seems to be a movement toward a rounder approach to the material, which allows for the addition of dance – it could almost be seen as a director wanting to get more bang for his buck. Therefore, younger singers and performers who are interested in operetta should absolutely work toward an awareness of their physicality/dance training as it might pertain to the needs of the production. As I said, much more dance is being incorporated these days, and those performers who can tick all the boxes will be the ones taking home the jobs. I was really thrilled that the students in Osnabrück had received such strong jazz and musical dance training and could dance quite well (in addition to being able to tap). It was just such a privilege to get to honor all that wonderful music!

Romina Markmann as Raka and Simon Staiger as Buffy in “Die Blume von Hawaii.” (Photo: Hochschule Osnabrück / Swaantje Hehmann)

You left most of the original dialogue intact, while most other recent productions offered serious re-writes. Why did you opt to stick to Grünwald/Beda? What’s special about their text, and why does it still work today? Does it work as well as the Marcellus Schiffer text for Alles Schwindel, also 1931?

Seiler: One of the things that always wows me about opera, theatre, and operetta is when you hear people sing lyrics or speak dialogue that was written 50, 100, or even 400 years ago, and you’re amazed at how fresh and modern the language and content sound. So, as a first step, I always look for that effect, because if it’s there, that link between the past and the present says so much more than any rewrite ever could. Also, attempting to translate everything to the modern day is running the risk of finding wrong analogies, or even losing something that is not necessarily comprehensible at first glance. Within the original Blume-dialogue and lyrics, I realized immediately that each character has material with its own individual tone – the material not only allows each character to have a distinct personality, but, most importantly, it’s still very funny. In fact, I only needed to do a few alterations of words or phrases, where I felt the joke might land even better if I would change them. And of course, a lot of dialogue had to be cut, because our sense today of what an evening at the theatre is – better to have one interval than two, and as funny as the show might be, not spending five hours with an operetta – is different than in 1931. What is not different, though, if you look at the audience reaction in Osnabrück, is that all of the jokes land: the funny parts are funny, the passionate and dramatic parts are touching. I think on the one hand, that’s because the situations the authors created have an ageless appeal for anyone, at any period in time (think of the scene with the love potion, where Bessie tricks Buffy into believing she’s attracted to any man who happens to walk by). However, I’m sure on the other hand, that we laugh even more, because we’re so excited, happy, and stimulated to see that we’re still connected to the people who lived and loved back in 1931.

Vidina Popov, Catherine Stoyan, Mehmet Yılmaz, Jonas Dassler, Alexander Darkow, Johann Jürgens in

“Alles Schwindel” at Gorki Theater, Berlin. (Photo: Ute Langkafel)

Alles Schwindel was a flop, back in 1931, Blume von Hawaii the greatest musical theater hit of the Weimar Era. (Even surpassing Dreigroschenoper, 1928.) Can you understand/explain why?

Seiler: I can only guess that it is like today: if you were to ask people if they’d rather go on a crazy trip to Honolulu and Monte Carlo, or instead spend an evening in Berlin, watching what kind of liars and frauds are living around the corner – who wouldn’t take the first? But there is no right or wrong, for one or the other. Instead, they complement each other, and both are fun to discover and watch. You need the grim, rough, cynical humor and reality of Schwindel in order to enjoy the charming, crazy, colorful fantasy trip to Hawaii – mix both, and you get a multi-layered, entertaining portrait of society back then and today.

Costello: Felix is absolutely right. My father didn’t work for Pan Am, so a trip to Hawaii for me, as a child, was unimaginable. Instead, I would faithfully watch every Road to… movie that Bob Hope and Bing Crosby ever made, and just dream of how exciting it must be to feel the tropical breeze underneath swaying palm trees.

A promotion picture for the Bob Hope & Bing Crosby “Road to” movie series from the 1940s.

If you imagine the situation in Germany as it was back back in 1931, and add that desperation as fuel to the tropical fantasy, it’s no wonder that people grasped at any opportunity to flee their reality, if only for a few hours. A few years later would see Depression-era Americans Flying Down to Rio for the same reason.

Honolulu is a still a magical place for many, with a distinct ‘look.’ Did you want to play with these Hawaiian elements or do something else?

Seiler: For me, the whole exotic Hawaiian atmosphere is so overwhelmingly present in Paul Abraham’s music that – and this is not intended as an excuse! – I really don’t know if I would want to see an exact replica of Hawaii, rebuilt as a set for the stage. I doubt that it could conjure up, with the same authenticity, all the images and feelings you have and experience when you listen to the music. Another thought continually struck me whenever I read the piece: it’s an imaginary Hawaii, a “Fantasy Hawaii,” if you will, for people who have never been there, but imagine it as the paradise they’re longing for, which adds a lot to the aura of the piece. And this is where escapism, and its appeal, come back into play: we were looking for a framework that would allow us to create this “Fantasy Hawaii,” not touching the structure of the piece so much as giving it the right angle to start it off and let its characters emerge from there. This is how we came up with the idea that Buffy needed to be the center of the piece, and to set him up as a lonely, frustrated worker in a warehouse for antiques. Bullied by his choleric boss (later: the Governor) and out of reach of the Boss’s timid, but lovely, assistant (later: Bessie), he falls asleep and begins to dream.

Simon Staiger as Buffy in “Die Blume von Hawaii,” dreaming the entire story. (Photo: Hochschule Osnabrück / Swaantje Hehmann)

However, instead of going to Hawaii in his dream, Hawaii comes to him, with all the characters climbing out of the wooden crates he usually stores the antiques in. To me, this idea of bringing this “Fantasy Hawaii,” with all its hula dancers and eccentric cast of characters to a rather cheerless place, always had more appeal than trying to recreate an authentic tropical landscape. And with the fact in mind that we had nine musical performers, playing all of the characters and chorus, complete with quick-changes, back and forth, into new costumes every time they would leave the stage, we tried to make a clear statement: Hawaii is the people who create its atmosphere.

Costello: When you look at the budget you’re given, and then consider what can and cannot be attained, it’s like a puzzle, or a mathematical formula: how can I get the most out of the resources I have. In this case, we knew that we could use certain props and costume pieces representatively, as symbols of a period or culture, in order to spark the imagination of the viewer and transport him or her to this world we had created. I was so excited to watch the students bring to life the various pieces that, individually, meant nothing, but that seen together, in context, in tandem with the lights and that beautiful, specific music, succeeded in carrying the audience into the fantasy we were spinning.

Dance rehearsal for “Die Blume von Hawaii” with the students of the Hochschule für Musik, Osnabrück. (Photo: Private)

Recently, Disney studios presented Moana as a musical film, set on a Polynesian island. Are such movies points of reference for your students when approaching a show like Blume? Or: what were their points of reference, or maybe their role models for operetta?

Seiler: In the beginning we talked not so much about Hawaii, but about the special era of the late 20’s and 30’s in which Die Blume von Hawaii flourished. Since I specifically didn’t want either the tragic story of Paul Abraham’s life, nor the killing of Fritz Löhner-Beda in a concentration camp, to become part of the performance, and wanted, instead, to present the work in all its glory and triumph, without sharing it involuntarily with the Nazis once again, I made a point of discussing it with the students. But once we began rehearsing, rather than offering the students too many references or operetta-like role models, it was much more important for me to see what could happen in the moment, when the material came together with their fresh and open-minded approach. It was absolutely stunning to see how they all simultaneously learned how to deal with the element of “seriousness vs. silliness” so commonly found in operetta. Once they had “gotten it”, and realized what the comparative difference was to what they had been playing before, it was such a joy for me to see how confident and curious they explored the rest of the operetta.

Costello: As far as my work was concerned, each time I would teach the students something unfamiliar to their European sensibilities, I would try to give them a sort of cultural lesson to illustrate what I was looking for. I found myself regularly discussing what I would consider to be the correct “posture” of the characters, both physical and behavioral. In America, we have not only an immensely diverse society, but also film and literary documentation to help understand the roots of the many cultures that make up our country. I tried to use my own education and experience to help pass on certain cultural observations that might help the students achieve a more authentic way of moving, both culturally and appropriately for the period. It is my hope that the students will always stay open and receptive for exactly those cultural offerings, like Moana, or even Magnum P.I., where they might glean things that can help bring authenticity to their performances.

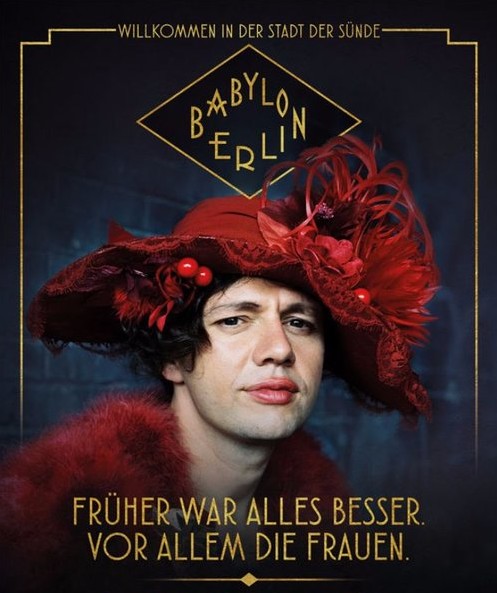

Movie poster for the series “Babylon Berlin,” welcoming viewers to the “city of sin” where “women especially used to be more beautiful.”

Are TV shows such as Babylon Berlin a source of information for students to understand the historic context of Blume von Hawaii? Do they know anything about the Weimar Republic, apart from Cabaret the movie?

Seiler: That’s an interesting question, which I don’t think I can answer for each of them, individually. My impression was that it might have worked the other way around: dealing with how to perform Blume will have helped make a connection back to what they already knew about that period, and, consequently, sparked an interest to go even further and learn more. When we came to the “Jonny” song, the historical context came alive in a very unambiguous way: can we really say “Bin nur ein N****r” on stage in 2018? Should we cut the whole song? Should we replace the word? We talked about Al Jolson and The Jazz Singer, which the authors surely had in mind when they wrote the number, but we agreed their specific intention would be understood differently today. Aside from the quality of the number, to maintain the integrity of the piece as a whole, we decided it would be a mistake to simply cut it. So, we came up with the idea of returning once more to our warehouse frame-of-reference, where Buffy finds, in one of the antique-filled wooden crates, the historic picture of the black-faced singer who played the title role in Krenek’s opera Jonny spielt auf. Having gotten drunk in the warehouse to fend off his frustration, Buffy hallucinates, thinking he sees the picture “come to life” and begin singing. Eventually, “Jonny” climbs out of the crate, clad in a black suit and white gloves, and involves Buffy in a painful and exhausting piece of vaudeville choreography.

Rehearsal room scene in Osnabrück: the student ensemble in “Die Blume von Hawaii.” (Photo: Private)

Costello: In a sense, though I am much older than they are, since I am not a native German, my knowledge of that period might be similar to the knowledge of the students, especially if they haven’t been paying attention in history class. I would hope, as I said before, that the students are open to receiving information about other cultures and periods in history through modern-day film and television, but I would add to that my hope that they be discerning in their choice of material. Whereas a show like Babylon Berlin might be very well done, and quite exciting, I am always very aware of the trend toward revisionist history, where contemporary mores and styles are superimposed upon historical situations when they are portrayed in film or in books. There is also the danger of omission of certain historical facts that some might find uncomfortable. I would always advise young performers and students of theater to find authentic narratives, either recorded on film or committed to paper, which give a true rendering of the time and the events which transpired in that time.

There is a big revival of Weimar era shows right now, with many great performances all over the place. How important is competition for operetta, and for your students?

Costello: I believe that competition is a good thing. Theater is a meritocracy (at least it should be), and the best productions will be those that are filled with the best of the best. When these students eventually “hit the world,” they will find other like-minded young performers who will be going for the same roles. Instead of becoming dejected by the seemingly small number of roles as compared to the relatively healthy number of applicants, they should find within themselves that competitive spirit that will bring them to work harder and train in a more focused way. By really observing the competition, both at auditions and in already-staged work, they will know exactly what they have to work on in order to prevail in the long run. The result of healthy competition is a raising of the bar, and an improvement in the overall quality of performance and in the spirit of professionalism and dedication to quality. This is the surest way of ensuring the enduring legacy of operetta and other older theatrical works.

For you, personally, what’s the secret of a good Abraham (or operetta) production that works in 2018?

Seiler: I always like it when you feel that a production embraces its “operetta-ness” and when it’s been seriously worked on, from the entertainment aspect that only an operetta can offer. That was, after all, the primary goal when those pieces were written – and unlike the way many of us think today, those pieces were not ashamed of being exactly what they are. And I don’t know if it’s a secret, but I think you can get a lot more out of an operetta if, instead of rewriting dialogue or adding (too many) new elements, you find the right measure of cutting dialogue and music. The worst operetta experiences I’ve had were the ones where I felt that the piece, the material itself, was so much smarter than what the production was giving it credit for.

Costello: Tempo, truth, and actors who listen to each other, even in hectic moments. The material is already brilliant. It just needs the respect of the people bringing it to life.

What are your next operetta projects?

Seiler: I’m directing Kalman’s Herzogin von Chicago at the Stadttheater in Bremerhaven in February 2019, which I’m already looking forward to! It has a lot in common with, and yet it is so different from Blume: Americans, escapism, jazz, Broadway vs. “Operetten-Seligkeit.” Even though it was written three years before Blume, the basic tone of Herzogin seems much more nervous and on-edge, and although escapism plays a large role in the proceedings, the piece itself deals more directly with society than Blume does.

The original Viennese “Roxy” team: Oscar Denes (l.), Rosy Barsony, and Hans Holt. (Photo: ORCA)

Costello: This year seems to be my operetta year, and that’s just fine with me. I will be doing productions of Fledermaus, Ball im Savoy, and Roxy und Ihr Wunderteam. The things that I have learned that I will take with me into upcoming productions have only partially to do with the actual operetta, Die Blume von Hawaii. The things that I learned came from the way Felix directed the words on the page. I was able to see how dialogue can be changed through action and intention, even subverted to another cause, giving it a depth that can’t be seen on the page. His careful, thoughtful work allowed for an extremely rich tapestry of ideas, which gave the students a challenging, and ultimately, very rewardingly full experience. I will take those ideas with me into my next operetta projects.