Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

29 June, 2015

It seems there is a new and inspiring wave of “history musicals,” with Hamilton on Broadway leading the way: a show about the life of American Founding Father Alexander Hamilton, with hip hop music, lyrics and book by Lin-Manuel Miranda. It turned out to be the greatest box office draw of the current Broadway season, because of its inspired novel way of story-telling, and its cheeky way of dealing with “national history.” The new show by composer Wolfgang Böhmer and author Peter Lund, Stella: Das blonde Gespenst vom Kurfürstendamm, labeled “Ein deutsches Singspiel,“ also deals with national history, in this case the history of the Federal Republic of Germany in the 1950s and 60s.

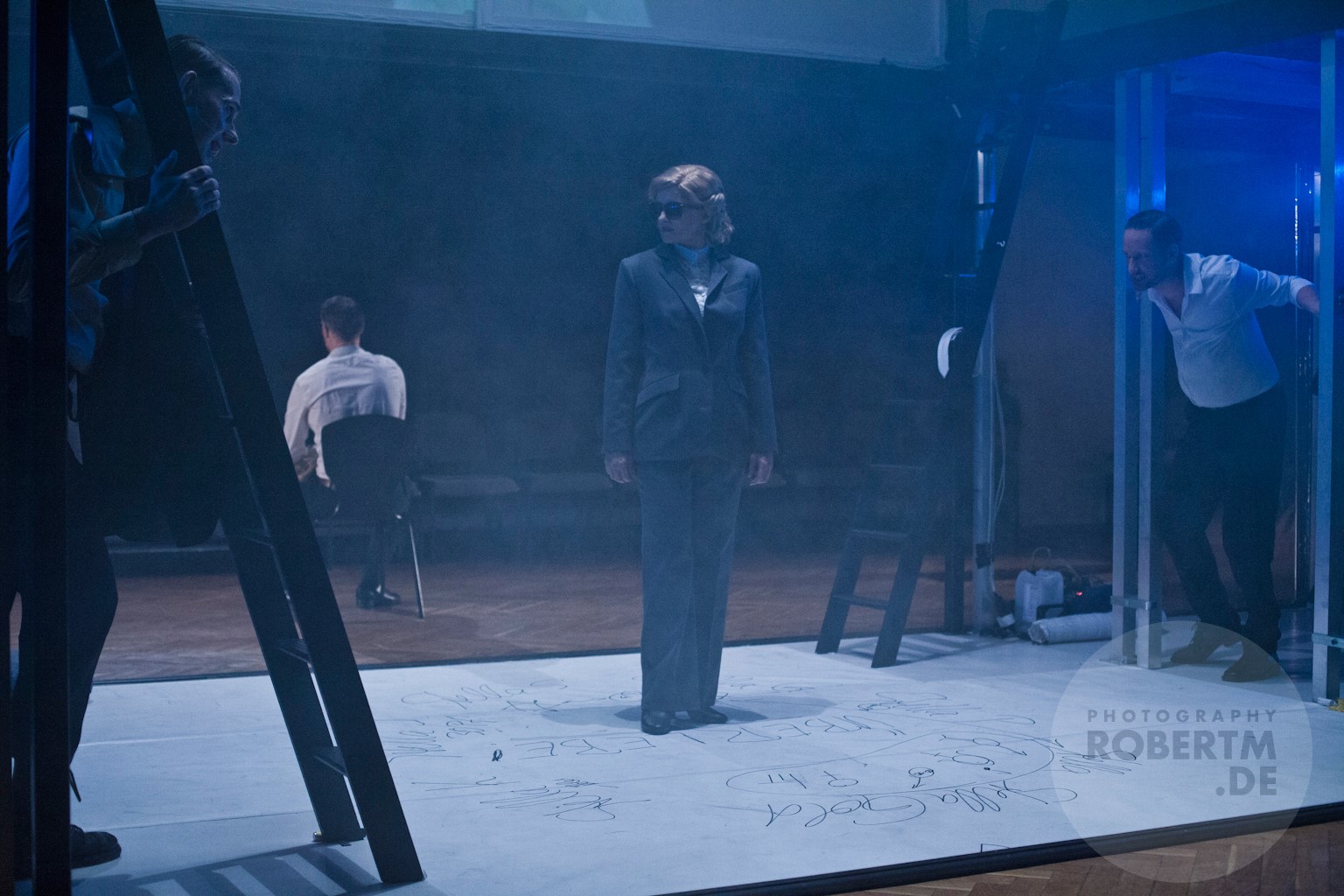

Scene from “Stella” at the Neuköllner Oper. (Photo: Robert M)

Stella asks the question: how did post-war society deal with Nazi crimes against Jews, and which crimes did the Jews themselves commit during Nazi times? Obviously, this is a complex topic with no easy answers, and the story of Stella Goldschlag demonstrates the complexity perfectly. She was a Jewish girl from Berlin, born in 1922, she dreamt of moving to the USA and of becoming a Hollywood star, but her family didn’t get a visa. So they stayed in Germany after 1933, and Stella began working for the Gestapo in the 1940s as a so called “Greifer,” someone who helped finding other Jews for deportation: 300 people, to be exact. Stella did it to save her own life, and that of her parents who were imprisoned by the Nazis. In the end, though, she couldn’t stop them from being deported and killed in Theresienstadt. She herself survived, as did her daughter Yvonne; possibly a child whose father was SS officer Walter Dobberke.

In 1946, Stella handed in a claim under a false name to be recognized (and financially compensated) as a “victim of fascism,” a claim that ended up in the hands of the Jüdische Gemeinde who remembered her actions and the many people who were deported because of Stella.

They put her in front of a judge, and she was sentenced to 10 years of prison in Russia (1947-1957). Upon returning to Germany, Stella was not allowed to see her daughter, who the Jewish Community had placed with a new family. Stella was infuriated by this, married an ex-Nazi, converted to Catholicism and become an outspoken anti-Semite. Many more court cases followed, in all of them Stella claimed that the accusations against her were a lie. She lived until 1994, when she committed suicide at age 72: a late sign of guilt which she had not shown (publicly) before?

Frederike Haas as Stella faces the courts in post-war times. (Photo: Robert M)

It is an emotionally charged story with many gripping moments, and posing various profound questions that are being discussed in Germany – also in the entertainment industry – at the moment. Peter Lund tells the story on two time levels, jumping back and forth between a chronological narrative of events, and moments in which Stella looks back at what happened, before dying. The dramaturgy is contrasting, focusing on the key scenes of the story: Stella’s dialogues with her father (who cannot believe his daughter collaborated with the Nazis), with her four husbands, with the Nazi officers (who blackmail her into working for them by threatening to kill her parents), with the judges, with her daughter (who refuses to see her as her mother because of the evil things Stella did), and with herself.

Isabella Köpke as Yvonne in “Stella.” (Photo: Robert M)

In contrast to the Hamilton Broadway model, composer Wolfgang Böhmer has not opted for a radical musical update, instead he has chosen music that is mostly reminiscent of Kurt Weill, with a few “modern music” sequences thrown in, possibly to demonstrate that this whole enterprise is intended to be serious. It’s actually the overture (or prelude) that starts like any German arts council funded “Uraufführung,” with off-putting atonal chamber music that made me want to get up and leave right away. But Böhmer soon comes round and delves into a more accessible sound world, familiar to anyone who knows his previous work with Peter Lund (Leben ohne Chris et al.)

Markus Schöttl singing a spooky waltz as Adolf Eichmann in “Stella.” (Photo: Robert M)

There are some effective musical numbers – spooky waltzes, snappy ensembles à la Sondheim’s Follies or Company, a slight hint of “degenerate” 1920s jazz, Volkslieder, synagoge chant – that are effectively sung by a superb cast. Frederike Haas as Stella-with-a-blonde-wig has an impressive voice that made me think of the young Ute Lemper; though Haas is a very different type of stage personality than Lemper. (She was seen, years ago, at the Neuköllner Oper in the dazzling production of Messeschlager Gisela.) Haas is also a convincing actress, portraying the “monster” Stella in such a way that one is never sure whether to despise her, or feel sympathy for her. Only Stella’s final song, in which she declares to be our “eternal Jewess” (“Ich bin eure ewige Jüdin, euer einziger deutscher Star”) came across a little too out-of-the-blue and too over-simplified: not Haas’s rendition of the number, but the song itself.

Jörn-Felix Alt as the slick Rolf Isaaksohn in “Stella.” (Photo: Robert M)

The men were equally impressive, especially Jörn-Felix Alt as Stellas ice-cold collaborator husband Rolf Isaaksohn. Mr. Alt has the rare ability to use his dazzling good looks to present a totally emotionless façade, while making it evident that it’s only a façade behind which absolute selfishness and cynicism hide. His duets with Miss Haas were chilling, as was the duet between Stella and her daughter Yvonne (Isabella Köpke) and the final encounter with her father, who she gets to accompany to the train taking him to Theresienstadt – a special favor of her Nazi “lover” so Stella could say good-bye.

Jörn-Felix Alt and Frederike Haas singing a chilling love duett in “Stella.” (Photo: Robert M)

Given the brilliance of the cast (Victor Petijean as Walter Dobberke, Markus Schöttl as Adolf Eichmann, David Schroeder as Stella’s father, Samuel Schirmann as Samson Schönhaus), given the great playing of the small band under the direction of Tobias Bartholmeß, and given the grandeur of such a story, I wished the music could have been more “special” – whatever that might mean.

Instead, it is a well-made score, absolutely serviceable, but rarely inspired in the way that “Hamilton” lifted its history lesson to a new level.

Which leaves the staging as the last point of interest. It was done by Martin G. Berger and played in a glass pavilion designed by architect Sarah-Katharina Karl. This pavilion was placed in the middle of the auditorium, so that the audience sits on either side of it. The upper part of the pavilion offered white walls on which black-and-white films were projected: live video images of the singers, clips from Marika Rökk dance sequences or other historic material. The rights for these must have cost the Neuköllner Oper a small fortune (video: Roman Rehor).

Filming herself live: Frederike Haas in “Stella,” together with David Schroeder as Father Goldschlag, Markus Schöttle as Friedheim Schnellenberg/A. Eichmann. (Photo: Robert M)

I found the glass house idea interesting, because it reminded the viewer: he/she who lives in a glass house should not throw stones! But other than that? It was not a particular convincing, or attractive, set for this story. What the director totally ignored was the fact that there are different time levels. In Berger’s staging there was no differentiation, of any kind, between the chronologically ordered scenes and the flash-back moments. If you didn’t read the synopsis in the program booklet beforehand, you probably ended up very confused by this staging.

Perhaps this is typical of young directors in Germany, working in subsidized theater (this production was made possible with money from the Berlin mayor’s office/Staatskanzlei Kulturelle Angelegenheiten, and other cultural institutions): they are so busy with video play, deconstruction, architecture, film projections etc., that they forget the all important art of story-telling.

It would be interesting to see “Stella” in a staging by Peter Lund, himself a fabulous stage director, just to see how he would handle the layers of the story.

The soloists of “Stella” lying on the floor, looking at the camera above, which creates the film images projected onto the glass pavillion. (Photo: Robert M)

Stella is a show that can touch an audience deeply. If this were Broadway, you could count the Neuköllner Oper production as a sort of try-out, after which the creative team would ideally polish up their work. With a cast like this, it’s definitely worth seeing Stella again, perhaps with a new, more in-depth finale and a different overture more in-sync with the rest of the score. And I would definitely like to see Stella in a more coherent – less self-absorbed – staging. Maybe then it would come across as a truly great and radical work. The story of Stella Goldschlag deserves such a radical treatment. And the story of Stella Goldschlag should reach a young audience that learns about the deeply twisted post-war history for the first time. And no, it doesn’t necessarily have to be hip hop!

The photos in this article are by Robert M, from Berlin.

Frederike Haas with blood all over herself in “Stella.” (Photo: Robert M)

Thank you for your detailed review and perception of our musical Play “Stella”!

Would it be possible to receive some photos from your photografer? Looking forward to hearing from you.

best wishes, F.Haas

I have passed your message on to Robert M, but you can also contact him directly via his website: http://www.robertm.de/