N. N.

The Era

1870

In his 2 volume biography Emily Soldene: In Search of a Singer Kurt Gänzl chronicles the initial success of opéra bouffe in London – as an import from Paris that made a major splash in Britain. The groundbreaking piece that established the new genre and performance style was not one of Offenbach’s many works (though they were performed too, with prominent actresses such as Hortense Schneider herself), but it was Hervé’s medieval farce Chilpéric that convinced the English that opéra bouffe and eventually ‘operetta’ was a form of musical entertainment they wanted to embrace. But what exactly was ‘new’ about opéra bouffe, and who embraced it? The newspaper The Era gave a lengthy analysis back in 1870 that’s worth re-reading today, as an early English language definition of opéra bouffe and ‘original’ operetta. Kurt Gänzl has kindly given us a copy of the article, it’s a review of a production that starred Hervé himself in the title role (which was later taken by Emily Soldene).

Article from The Era describing “Chilpéric” in London, 1870.

The singers and the orchestra have now quite settled down to their work, and Chilpéric goes nightly more successfully, while the rising popularity of the opera is very marked, more especially amongst the habitués of the stalls. Every evening side chairs filling the gangways and passages are occupied, while the private boxes unmistakably show that fashion has quite accepted Chilpéric.

That Chilpéric was an experiment is not to be denied. Opéra-bouffe in England had scarcely an existence, and an English audience was not prepared for its peculiar construction. An English audience, moreover, has for a long time associated burlesque with ten-syllable rhyming lines, the absence of which in Chilpéric would have been a distinct innovation upon precedent, but for the production of Mr Gilbert’s The Princess at the Olympic only a week or two previously. Indeed, if the trial at blank [verse] burlesque at the Olympic was venturesome — for the attempt at the same house by Mr Best and Mr Bellingham in Barbe-bleue to do away with rhyme in burlesque had signally failed – the risk at the Lyceum of producing a burlesque without rhyme, or even rhythm, was much more evident. The difficulties that have been overcome at the Lyceum were many. The drawback of the principal actors singing and talking in a language not perfectly known by them was great [...] but the chief obstacle, apart from the libretto altogether, which may be said to be disguised by the obscurity of the language in which it is for the most part represented – the chief obstacle was the musical form of the work, one quite unknown and unfamiliar to English audiences.

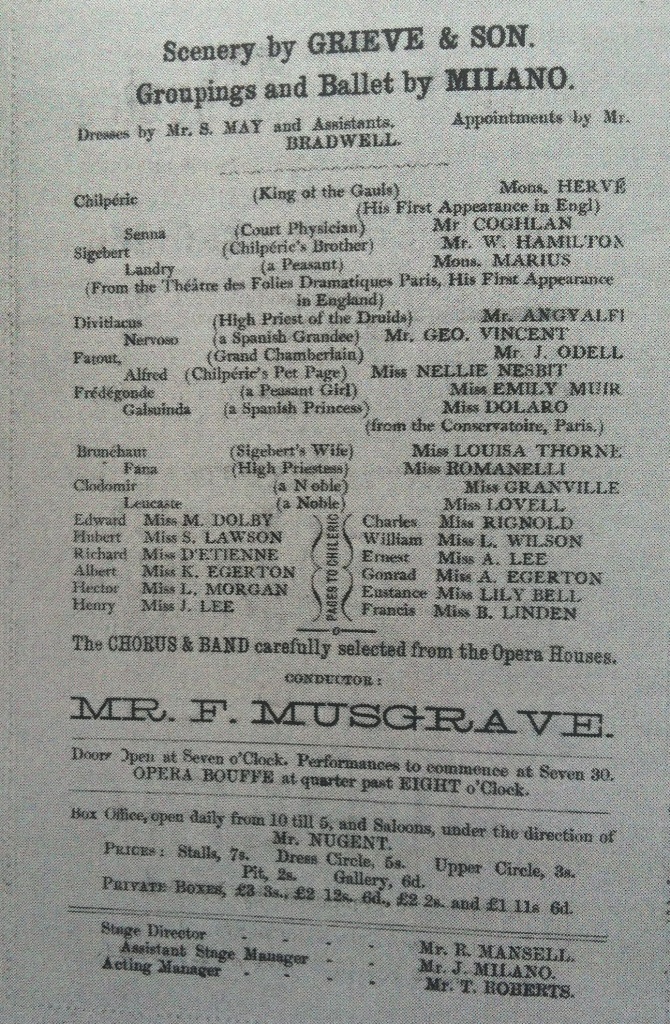

Poster announcing “Chiléric” at the Lyceum Theatre, London, with Hervé in the title role. (Photo: Archive Kurt Gänzl)

The mass of visitors to the Lyceum are prepared to hear comic opera; they are not at all prepared to hear what appears to be grand opera suddenly pulled up at a crisis. Now that is exactly what modern opéra-bouffe is, and what, perhaps, that of the past was. The natural guardedness with which we in England look upon a new form of art, whether high or low, had led to a sort of mistrust at this first attempt at opéra-bouffe on English boards. That in the music which is intended to create musical bathos is looked upon with a sort of critical suspicion rather than good humour, and a wrong effect is produced. The pit is beginning to comprehend the joke of the operatic element in Chilpéric and nightly increasing clattering laughter is the result; but the remainder of the audiences, especially the stall audience, sit quite gravely through the evening, and go away apparently puzzled. As to the gallery, whether the fact is caused by the absence of the popular gallery entrance fee, sixpence, or the want of sympathy with the performance, it is almost deserted.

Cast list for “Chilpéric” at the Lyceum Theatre, London, with Hervé in the title role. (Photo: Archive Kurt Gänzl)

The burlesque music of Chilpéric it has been said creates a wrong effect upon an English audience. For instance, in the second act, where Frédégonde enters with her truck of household goods, the scena she sings whilst holding on to the handles is a burlesque upon Meyerbeer’s ‘Robert, toi que j’aime’, the great air for the Princess in Robert le diable. The mass of the auditory recognising the familiar phrases, no doubt are amazed at M Hervé’s apparent audacious plagiarism. It requires preparation and watchfulness to comprehend the ‘bouffe’ which is really going on in the scoring while Frédégonde is uttering the progressing phrases for which the original morceau in question is famous. But, to the initiated, this burlesque passage is perfectly worked out in the final resolution of the passages into the ridiculous, a resolution which practically and critically alarms many as a musical outrage. So, in another part of the opera, Frédégonde has to burlesque the music given to Marguerite in the last act of Faust. That which in M Hervé’s composition appears his audacity is in reality his ability, the proof of his fitness to write the opéra-bouffe as distinct from the opéra-comique.

Sheet music cover for the “Chilpéric Waltz,” London 1870. (Photo: Archive Kurt Gänzl)

But Chilpéric is by no means wanting in good, original, comic music, or in efficient musical compositions. The opening phrases for the wind instruments, which lead the overture, are really in the second degree masterly, while they pass into the following waltz neither abruptly or confusedly. The succeeding gallop, of the phrenetic school, which completes the rapid and broadly written overture, now brilliantly played, very appropriately leads to and contrasts with the opening piece of the opera, the scena for the Druid priests and his followers. Here, we have music of a massive character, essentially parodying the choral music of Norma, while it contrasts admirably with the rakish strains which follow it, and are due to the hunters. The opening air for the heroine Frédégonde is quite an original valse movement, simple, yet varied. But the aptness of M Hervé in suiting his music to the sentiment, or want of sentiment, in the words to which it is wedded, is only seen when Chilpéric sings his hunting song upon horseback. The idea of rollicking gallop in music was never better illustrated than here. There is nothing very remarkable in this number as a musical effort, but its vivacity is remarkable. This ability is the more marked in the ‘Butterfly Song’ in the second act. The prelude is especially suggestive of the fluttering of a butterfly. By the way, this bouffe romance has been sadly shorn of its Parisian proportions.

Hervé as the “compositeur toqué” at a Café-Concert, 26 mai 1867. (Photo: Palazzetto Bru Zane)

In the storm music, both of the elements and the high priestess, the sense of confusion is effective and contrasts aptly with the final morceau of the first act, one which our French friends would call a galop infernale, but which may preferably be described as a phrenetic gallop. The second act is, from a musical point of view, especially noticeable for the air given to Galusinda, whose charming seguidilla is good Spanish music brightened by a French hand. The second piece given to Galusinda, in the last act, and which is really composed of some rather frisky couplets for the bride, and which she sings in her wedding white satin, is now dispensed with, regrettably from a musical point of view, for it was quite original. The brindisi-waltz for the pages in the second act, the guitar romance given to Landry, and the butterfly song in this same second act would, if set to other words than those of the opera, assuredly sell as drawing-room music. The last act is musically short and hurried.

C. D. Marius as Landry: the “masculine masher” in Hervé’s “Chilpèric.”

It is especially remarkable for the mock heroic march which heralds in the army [and the king] who has conquered all his enemies in his white satin wedding dress and in five minutes. The absurd and the grand have never been better mixed. As a burlesque, this opera bouffe goes better nightly – at the expense of the music, however, for as in England burlesque actors are rarely musically educated singers, and as English singers eschew burlesque, for the simple reason that solid singing pays them better, and, as it would be quite out of the question to have the whole of the characters at the Lyceum played by Frenchmen speaking more or less impossible English, it has resulted that much of the original music is mutilated, more positively cut out, in order to get in English actors, who shine as absolutely by their burlesque qualities as they do not shine by their musical qualification. The result is that the English section of the dramatis personae make the audience laugh with what they have to say, while the Frenchmen present their music as admirably as their voices will admit of (and it is astonishing how much may be done by art to overcome natural inflexibility and want of range of voice), and the ladies do their work admirably.

The cover for volume 1 of Kurt Gänzl’s “Emily Soldene: In Search of a Singer” (2007).

Special thanks to Kurt Gänzl for letting us put this article online. His book Emily Soldene: In Search of a Singer (2 volumes) was published in 2007 by Steele Roberts Ltd, Wellington, New Zealand. [info@steeleroberts.co.nz].