Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

26 January, 2017

Any operetta compilation that starts with Charles Kullmann singing “Als flotter Geist, doch früh verwaist” like this has my immediate and full attention. It’s a recording from Berlin 1932, with the orchestra of the Staatsoper conducted by Clemens Schmalstich. And it’s track 1 on Viennese Operetta Gems: Original Recordings 1927-1949. They were put together and restored by Peter Dempsey and first released in 2003. Which is quite a while ago. But it’s such a fascinating disc that I have come back to it again and again. Because it demonstrates that if you like your operettas sung by opera singers there are enormous differences between, let’s say, Mr. Kullmann and Julius Patzak, or Elisabeth Schumann and Gitta Alpar, not to mention Dusolina Giannini. Also, this 20-track compilation mirrors important repertoire changes that happened during the 1930s.

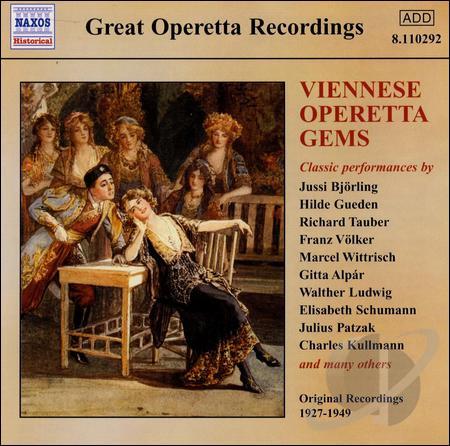

CD cover for Naxos “Viennese Operetta Gems.”

All recordings on this disc are outstanding, in their own way. But some are more outstanding than others. Among the absolute knock-out performances is Gitta Alpar singing “Rosen aus Dschaipur” from Kalman’s Bajadere in Berlin 1932, with Herbert Ernst Groh and the Otto Dobrindt orchestra. Alpar was at the height of her fame in 1932, and the way she turns this expansive “oriental” waltz into a seductive act of love-making needs to be heard to be believed. Her top notes are screams of ecstasy, she soars from shivering climax to climax with the utmost ease, and she uses lots of portamento inbetween. The seductive power of 1920s operetta is nowhere more audible than here. It’s exactly this kind of “seductiveness” that the Nazis soon after labeled “degenerate”. Kalman’s works – and similar titles by Granichstaedten or Abraham – disappeared from German theaters. On this disc, Kalman’s “Komm’, Zigan” sung by Marcel Wittrisch with the orchestra Ernst Hauke was recorded in Berlin 1932 – i.e. before the big turning point.

There is a similar seductiveness in Tauber’s version of “Im Chambre séparée”, also recorded in Berlin 1932, conducted by Erich Wolfgang Korngold (!). Like Alpar, his colleague and rival, Tauber knows the art of love-making through music. It’s amazing to hear, even after all these years, how he glides through the notes and uses them to lure the listener in. You can tell that all the other tenors on this disc have studied Tauber’s way of singing closely, and copy the basic success elements as best as they can.

After 1933, contemporary operetta more or less disappears and is substituted by a revival of older “classic” Viennese operettas by Strauss, Ziehrer, Suppé and others. So instead of Bajadere you get Elisabeth Schumann singing “Sei gepriesen du lauschige Nacht” from the rediscovered “Golden Operetta” Die Landstreicher; recorded in London in 1937, for the German market, one may assume. Though Schumann was a light coloratura soprano like Alpar, the difference between the two ladies could not be greater. Where Alpar is a “singing vamp” of Mae West allure, Schumann is a chaste soubrette. (Which is a contradiction in itself.) Obviously, she sings classically beautifully and refined, but there is no seduction – and no “degeneration”.

It’s the historic moment where operetta starts to become incredibly boring. Great stars such as Schumann could make you forget this boredom. But once the singers were not of that caliber anymore, it’s blatantly obvious what damage the Nazis inflicted on the genre.

Because of Hitler’s “friendship” with Mussolini, there were many Italian performances in the Third Reich; one of them is Dusolina Giannini recording “Lippen schweigen” with Marcel Wittrisch in Berlin 1938, with Bruno Seidler-Winkler conducting. The two produce lovely – even heroic – notes, but no characters that are even remotely related to what The Merry Widow is about, as shown by Erich von Stroheim or Ernst Lubitsch in their film versions.

Two years earlier, Joseph Schmidt recorded “Ich bin ein Zigeunerkind” from Lehár’s Zigeunerliebe in Berlin. It’s amazing to hear such a late Schmidt recording from Germany; and it’s amazing to hear the sorrow and overwhelming despair in his voice. It’s shocking. Especially when you know how the story of his life continues, and when you know what the Nazis did with “gypsies.” (I know the term is politically incorrect these days.)

Right after Schmidt comes Franz Völker on this disc, singing “O Mädchen, mein Mädchen” from Lehár’s Friederike. You might wonder: didn’t the Nazis take the Goethe operetta off the repertoire because it was considered inappropriate as a representation of the great German author? If you look closely, you’ll see that this recording by the famed Third Reich Heldentenor was made in 1928, just after the world-premiere of the show, created with Richard Tauber in the male lead. Back then, Völker was only a cheap substitute for Tauber, the star of stars. But his voice already glows with the promise of his later career.

As is well-known, the Nazis substituted many “degenerate” operettas with new ones written by their new “Aryan” composers. One of the substitutes for Kalman’s and Abraham’s Hungarian flavored shows was Monika by Nico Dostal. Here, you can hear Anni Frind singing “Heimatland” in Berlin 1938. Again, it’s a far cry from Gitta Alpar, who is also represented with “Bin verliebt, so verliebt” from Lehár’s Schön ist die Welt (1930).

The disc closes with Hilde Güden singing “Liebe, du Himmel auf Erden” from Paganini, recorded in London 1949. Güden was one of the post-war glamour stars in operetta land, with a wonderfully characteristic soprano, but again without the “degenerate” seductiveness that Alpar as a similar type of soprano once brought to the genre.

I’m afraid that kind of vocal seduction has vanished from the operetta world.

It’s certainly gone already when Julius Patzak sang “Hab’ ich nur deine Liebe” from Boccaccio in Berlin 1934, or the “Lagunenwalzer” in the same year.

Closer to the Alpar ideal, and still working in Nazi Germany, is Lillie Claus whose superlative version of “Schenkt man sich Rosen in Tirol” is included here, recored in Berlin 1940. But whereas Alpar sang contemporary operettas, often written for her, Claus here sings 19th century operetta classics revived by the new men in charge.

If Kullmann’s “Flotter Geist” is the fantastic opening track and Alpar’s “Rosen aus Dschaipur” the non plus ultra of operetta sex, then you should also try Tauber and Jarmila Novotna singing “Schön wie die blaue Sommernacht” from Giuditta, recorded in Vienna 1934. Lehár conducts the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. That, too, is glorious over-the-top operetta singing oozing erotic frizzle that disappeared in Austria as well after 1938. To have it all preserved here and mixed up by Naxos is a treat.

Strangely, Mr. Dempsey does not mention any of the political background in his booklet essay. Instead, he muses on the “mythical” Vienna that these shows evoke, though Bajadere hardly has anything to do with “Alt-Wien,” even if it premiered in Vienna in 1921. But that doesn’t make this compilation any less interesting. In the end, I asked myself: where are the other Kullmann operetta recordings? (Can someone please release them, soon?)

Are you suggesting that Elisabeth Schumann’s style of singing operetta is a prodict of the Nazi era? What makes me doubt this is that she sang operetta in this way before the Nazi era.

The recording in question, Ziehrer’s “Sei gepriesen du lauschige Nacht” from LANDSTREICHER, was made in 1937, in London for HMV. It fully represents the particular post-1933 operetta style cultivated in Germany. Schumann might have sung operettas before the Nazis came to power, as encores or bonus tracks, but she was never an “operetta star” like Adele Kern or Gitta Alpar (or Jarmila Novotna). To hear her with this stylistic approach in the late 30s can be interpreted as a political statement, comparable to Erna Berger’s operetta recordings. I am not suggesting that the singers themselves shared the political ideals of the Nazis, but they participated in redefining the genre in a way Nazi ideology wanted.

Thanks, Kevin, for your comment. I think that if Elisabeth Schumann’s pre-Nazi era operetta singing is similar to her 1937 operetta singing, then it is not reasonable to suggest that her 1937 singing is complicit with Nazism. My understanding is that she hated Nazism, and that led her to leave Germany in the late 1930s. I suspect the 1937 recording was made in London because by then she was no longer living in Germany. What would have motivated her to make the pro-Nazi political statement you see as a possibility in her case?

Good Morning,

I am doing research for a friend and I was hoping that you could possibly help me.

We are looking for information regarding Eduard Heil (Edy Heil) He was an operetta singer in Germany. The following venues is where he performed:

Stadt Theater Gottingen (10/1/32 – 3/31/34)

Stadt Theater Gelsenkirchen )10/1/36 – 4/25/37)

Stadt Theater Bremerhaven (8/10/38 – 5/9/40

Central Theater Dresden (6/7/40 – 7/31/40)

Stadtische Buhnen Halle Saale (9/1/40 – 8/31/47)

Thalia Theater Hannover (8/1/47 – 7/31/49)

Deutsches Theater Munchen (1/6/50 – 2/5/50)

Hamburger Volksoper (3/25/51 – 4/30/51)

We are looking for any archived recordings of any of these operettes.

We welcome any information or links that you can provide.

We thank you for your cooperation in this matter.

Looking forward to hearing from you soon.

Helen Flack

Huntingdon Valley, PA USA