Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

12 July, 2016

Librettist and lyricist Michael Colby has written musicals such as Charlotte Sweet and Tales Of Tinseltown, both have just been released on CD. Other works include Slay It With Music (Off-Broadway and London) and Ludlow Ladd. Colby was chief writer for the Drama Desk Award-winning New Amsterdam Theatre Company, and has been a writer for The NY Festival of Song, as well as the Theatre By the Blind. Also, he’s the author of the autobiographical book The Algonquin Kid: Adventures Growing Up at New York’s Legendary Hotel, and he was researcher for Dorothy Hart’s biography of her brother-in-law Lorenz. We caught up with Mr. Colby to speak with him about his work – and how it is influenced by operetta. Here are his often surprising answers about classic musical comedy as compared to not-so-old-fashioned operetta, and about how to make the genre(s) appeal to all generations.

Michael Colby sings “Growing Up at the Algonquin” (music: Ned Paul Ginsburg) at the Algonquin Salon. (Photo: Archive Michael Colby)

Your musicals have a strong sense of “nostalgia,” which is something that links them to great vintage musical comedies, but also to Broadway operettas by Herbert, Romberg, Friml et al. Did you have any defining operetta moment in your life that made you fall in love with the genre?

From an early age, I was enamored of musical theatre, past, present, and future. I was fortunate to grow up in a time when there were still Broadway revivals of such operettas as Romberg’s The Desert Song and frequent TV showings of Jeanette MacDonald/Nelson Eddy films like Friml’s Rose-Marie and Herbert’s Naughty Marietta. An annual New York/November ritual was the TV showing of the movie of Victor Herbert’s Babes in Toyland (with Laurel and Hardy; aka March of the Wooden Soldiers); the operetta was broadcast on Thanksgiving Day and I rarely missed it.

When I was 11 and in sixth grade, I likewise became a Gilbert & Sullivan fan after being cast in the title role of The Mikado. In my late teens, I was fascinated by Rodgers & Hart operettas like Dearest Enemy and the all-sung, all-rhymed sections of their movies, Hallelujah I’m a Bum and Love Me Tonight (which, incidentally, the late, great lyricist, E.Y. Harburg, once cited to me as a major inspiration for his Munchkinland sequence in The Wizard of Oz).

These influences found many ways into my life.

As a kid, long before its use in Thoroughly Modern Millie and Young Frankenstein, I’d blurt out “Ah Sweet Mystery of Life” at the strangest times. At college, I submitted mini-operettas to Waa-Mu, the campus show at Northwestern University (Alas, none was chosen).

Having a special knack for all-rhymed musicals, I wrote many of my earliest musicals in the all-sung, all-rhymed tradition, including the Christmas operetta Ludlow Ladd and its sequel Charlotte Sweet. Both these shows were influenced by Babes in Toyland. The second half of Ludlow Ladd takes place in the Land of Yuletide Cheer, populated by fairy tale characters (à la Toyland). In Charlotte Sweet, the villain—exploiting a debt—is named Barnaby, as was the hissable cur in Babes in Toyland.

Michael with his idol, the late E.Y. (“Yip”) Harburg. (Photo: Archive Michael Colby)

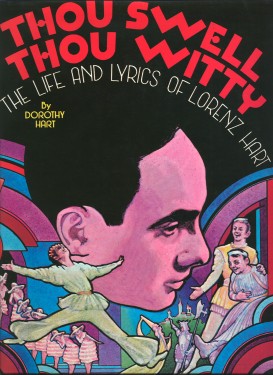

In subsequent years, my knowledge of operetta landed me positions at the Berkshire Theatre Company (Stockbridge, MA) and as a founding member of The New Amsterdam Theatre Company. At Berkshire Theatre Co., I was musical theatre advisor—overseeing major revivals of two musicals with operetta elements: Rodgers & Hart’s I Married An Angel and the Gershwin/Kaufman/Ryskind show Let ‘Em Eat Cake (a sequel to Of Thee I Sing). I was chosen to be researcher for Dorothy Hart’s biography of her brother-in-law, Thou Swell, Thou Witty: The Life and Lyrics of Lorenz Hart. This included looking into his movie lyrics for the movie version of Lehar’s The Merry Widow; and his operettas (such as the all-sung, all-rhymed Chee-Chee, a show about a Eunuch with surprisingly few cut songs given the subject).

I was treasurer and frequent writer for The New Amsterdam Theatre Company, founded by Bill Tynes, a forerunner of “musicals in concert” presentations.There, our presentations included concert versions of such operettas as The New Moon, Eileen, The Firefly, and Sweethearts. Collectively, these experiences continue to inform my writing.

The only nude shot of Michael Colby. (Photo: Archive Michael Colby)

Many Broadway fans make a sharp differentiation between “good” musicals and “bad” operettas; as if the two genres were completely separate and either/or alternative; when, in fact, operettas were everything the legendary “integrated musical” post-Oklahoma is supposed to be. How did operetta get such a bad reputation among Broadway aficionados?

What Oklahoma! did was popularize and help refine integrated musicals. One can cite various examples of earlier “pioneers,” such as Show Boat and the Princess Theatre musicals (by Wodehouse, Bolton & Kern). I’ll single out Rodgers & Hart’s Peggy-Ann (1926), which incorporated many of the elements for which Oklahoma! is credited. It didn’t open with a big chorus number but rather with a relatively intimate book scene. The first song wasn’t performed for approximately 15 minutes into the show. Songs and scenic elements reflected the topsy turvy plot: a girl’s wild Freudian fantasy of traveling to New York and beyond.

As for “good” and “bad” musicals, much of a show’s reputation hinges on its book/libretto—whether the show be operetta or traditional musical.

As someone who wrote narrative adaptations for the New Amsterdam Theatre Company, I can tell you firsthand that some books are creaky, dated and/or amorphous; others surprisingly sturdy and timeless. It also doesn’t hurt when you have a score like The New Moon, with so many numbers that are highly stage-worthy and feature classic melodies.

What particularly annoys me about judging old shows is when the naysayer overlooks the era in which they were written. Historical context is so important in judging a vintage musical as well as tracing how musical comedy has changed through the years. On one hand you can say that material and writing formats have evolved, becoming more sophisticated. On the other hand, you can say musicals these days have devolved with an emphasis on vulgar language, technical effects, and lyrics that are sloppily formed and rhymed. As to how operetta got a bad reputation, it’s like fashion—most people just lean toward what’s popular today not realizing that future generations may likewise censure passing styles.

You probably know the Pirates of Penzance production form Central Park. Why was that seen as a “one off” positive production, and not the standard that should be applied to all operettas, not just the Gilbert & Sullivan variety?

I saw that production when it began in the park. I loved it, especially since the inceptive production boasted the best “Ruth” imaginable, Patricia Routledge. I think Penzance’s success had a lot to do with the perfect pieces falling into place: an impeccable staging (by Wilford Leach and Graciela Daniele), a high-profile, commercial cast (Linda Rondstadt, Kevin Kline, et al.) and the Public Theatre’s being on a commercial roll with its other productions (hits like A Chorus Line and That Championship Season).

Through the years, there have been other G & S anomalies, like during the late 1930s when The Mikado was getting all kinds of then-contemporary stagings: e.g. The Hot Mikado and The Swing Mikado, both African-American versions done on Broadway. We know about these highly publicized Gilbert & Sullivan productions, but there have been countless variations of G & S that got nowhere—for diverse reasons.

Two of your shows – Charlotte Sweet and Tales of Tinseltown – were recently released on CD. Are they new recordings or re-issues? And were they recently written, or are they older shows that are being rediscovered?

A longtime dream of mine has been to record Tales of Tinseltown (composer: Paul Katz), a personal favorite. The show has developed considerably since the original production in 1985. The original off-off Broadway production was another of my all-sung, all-rhymed musicals. In subsequent productions, I found the material worked best when I converted scenes into straight dialogue, so the show was closer in style to the actual movie musicals of the 30s, with screwball dialogue, as well as rhythmic dialogue (rhymed and sung) in the tradition of Rodgers & Hart’s Love Me Tonight.

“Tales of Tinseltown” session at PPI Recording Studio: Michael Colby, Paul Katz, Tony Yazbeck (Photo: Joe Clarke).

Many productions—with changes and new material—followed, capped by a hugely successful production in (of course) Hollywood. Finally, last summer, I was able to raise the money to record the show, speaking with several labels about releasing it. John Yap of JAY Records was extraordinarily supportive. He not only offered to release Tales of Tinseltown but to reissue Charlotte Sweet in a 2-CD edition (previously there was a shortened version available on CD, based on the 2-LP set of the original production, released in 1983). In addition, John has offered a free bonus to those ordering Charlotte Sweet at www.JayRecords.com: a private recording of Ludlow Ladd, the prequel to Charlotte Sweet, with that show’s original cast (note: Ludlow Ladd has been refined and expanded since that 50-minute recording was made). Both Charlotte Sweet and Ludlow Ladd were composed by the late Gerald Jay Markoe.

Ken Fallin portrait of “Tales of Tinseltown”. Bottom (from left): Christina Bianco, Jake Epstein, Klea Blackhurst, Nat Chandler, Harriet Harris. Top (from left)-Tony Yazbeck, Alison Fraser, Richard Kind. (Archive Michael Colby)

Your Tales of Tinseltown have a remarkable orchestral sound and superb “character” cast. Who are these singers, how did you find them, and how did you get Larry Hochman to join you team?

Thanks so much for those kinds words. Musical director Michael Lavine and I rounded up this dream cast, all with whom we’ve previously worked.

Two of the CD cast members originated their roles: the timeless Nat Chandler and Alison Fraser. Nat played leading roles on such shows Phantom of the Opera (Raul) and The King and I (Lun Ta opposite Yul Brynner). Alison was the original Trina in William Finn’s March of the Falsettos, was Tony nominated for Romance, Romance and The Secret Garden, and just received all kinds of praise and nominations playing Betty Ford and Nancy Reagan in Michael John LaChiusa’s First Daughter Suite.

“Tales of Tinseltown” session: Christina Bianco (Photo: Joe Clarke)

Christina Bianco, who plays Ellie Ash (“The Girl of a Thousand Sounds”) on the CD, is a 2-time Drama Desk Award nominee and YouTube phenomenon, known for her astonishing impersonations; she truly is “The Girl of a Thousand Sounds.”

Klea Blackhurst is an award-winning star of stage and cabaret, who’s often cast in Ethel Merman roles including playing the great belter on the album of the musical, The Merman’s Apprentice.

“Tales of Tinseltown” session with Jake Epstein. (Photo: Joe Clarke)

Jake Epstein is the Canadian TV star of Degrassi, who played the title role in the Broadway musical Spiderman and originated “Gerry Goffin” (Carole King’s husband) in the Broadway smash Beautiful. The hilarious Harriet Harris won the Tony Award for Thoroughly Modern Millie and is known to TV audiences for her work on Frasier and Desperate Housewives.

Richard Kind, the voice of “Bing Bong” in Disney’s Inside Out, has extensive credits, including TV’s Mad About You and Spin City, as well as Sondheim’s Bounce.

Tony Yazbeck won the Fred Astaire Award and was Tony nominated playing the Gene Kelly role in On the Town, as well as starring on Broadway in Finding Neverland. Even our four-singer chorus features such performers as Samantha Massell, currently playing Hodel in Broadway’s Fiddler on the Roof.

I first met Larry Hochman (Tony winner for Book of Mormon) when he orchestrated a production of Tales of Tinseltown at the George Street Playhouse (New Jersey, U.S.) for producers Sondra Gilman and Celso Gonzalez-Fallà. He has been an incredible friend to me and worked on the album as a labor of love.

“Tales of Tinseltown” recording session: Richard Kind & musical director Michael Lavine. (Photo: Joe Clarke)

Tinsel Town is a concept album. If I compare it with new operetta recordings – even of Broadway classics such as Albert von Tilzer’s 1922 The Gingham Girl or The Auto Race (1907), A Lonely Romeo (1919), The O’Brian Girl (1921) or Queen High (1926) – made by the Operetta Foundation in Los Angeles, I wonder: why can’t they get a glorious sound like you have onto disc, with comparable singers? Is it a matter of finance or of ideals? Roger Neill and Julien Nitzberg managed to get the great 2006 operetta The Beastly Bombing recorded in LA with a similar outstanding character-cast as you, with hardly any budget. Does that mean the “traditional” operetta people could learn something from you, to think bigger and more extravagantly?

Ah, we return to Rodgers and Hart. A Lonely Romeo interpolated a song which marked their Broadway debut: “Any Old Place With You.”

Cover of Dorothy Hart’s biography of her brother-in-law Lorenz. Michael was researcher. Art: Frederic Marvin.

I can’t generalize. I wouldn’t necessarily say you have to think bigger, just have good instincts (and a lot of luck) on whom to cast and where to record. I couldn’t have been luckier on the cast and company I assembled. We had to work around their schedules, with staggered recording sessions from June through August last summer. Many performers recorded separately—their parts seamlessly edited together by our studio engineer Chip Fabrizi of PPI Studios in NYC. Another major factor was our CD producer, Jeffrey Lesser, IMO the best in the business, whose schedule we also worked around. Jeffrey came aboard on the enthusiastic recommendation of Larry Hochman.

He has worked on albums for Barbra Streisand, Joni Mitchell, Lou Reed, Kristin Chenoweth, and musicals by Robert Jason Brown, Jonathan Larson, and William Finn. His instincts and guidance of the performers proved nothing less than brilliant.

The current hits on Broadway are Hamilton and the Disney movie-to-stage adaptations. Why do you think it’s important to offer a Colby-alternative today, pointing back to past greatness to move into the future?

It’s so expensive and difficult to get new musicals produced in New York, I think all the writers who make the attempt are brave hearted warriors; and shows that keep performers employed are vital to its future. I personally prefer classic shows like Carousel and Show Boat – along with concept musicals like Cabaret and Company – to rock musicals. But there should be room for all.

My musicals are conceived as small-scale epics, with casts of about eight and emphasis on story-telling. Because I try to make all roles important and strive for comic surprise, casts seem to have a ball doing them.

I can only hope future generations will appreciate that most of my musicals are originals, not based on any other source.

For example, Charlotte Sweet has several unusual elements: besides being all-sung and all-rhymed, plus revolving around holidays (St. Valentine’s Day, Christmas, and New Years Eve), it incorporates the three forms of entertainment most popular in Victorian England: music hall, melodrama, and Gilbert & Sullivan type operetta. But, perhaps most unique of all, Charlotte Sweet, spotlights characters—a Victorian “Circus of [Freak] Voices”—whose personalities are as defined by their voice types as the characters in Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf are delineated by musical instruments.

Scene from the 1982 “Charlotte Sweet”. The Circus of Voices (clockwise): Lynn Eldredge, Merle Louise, Mara Beckerman, Polly Pen, Michael McCormick, Jeff Keller. (Photo: Elizabeth Wolynski)

As for Tales of Tinseltown, my goal has been to encapsulate the entire range of musical movies of the 30s, with unexpected twists. As an illustration, there’s one sequence that evokes everything from the musicals of Shirley Temple to Busby Berkeley to Jeanette MacDonald/Nelson Eddy. Except in “Tinseltown”, the chorines tapping on an airplane (like in Flying Down to Rio) don’t necessarily stay on the wings; the “Maytime” style duet is sung by the sweethearts, Esmeralda and Quasimodo (Note: this duet is from the original version of “Tinseltown,” long before Disney turned “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” into a songster). Another twist is that Ellie, the central character perceived as America’s wholesome ingenue on-screen, isn’t so wholesome off-screen (But she learns her lesson: beyond its frivolity, the show is a cautionary tale of compromised values).

Recording session for “Charlotte Sweet” in 1982: (from left) Christopher Seppe, Jeff Keller, Michael McCormick, Lynn Eldredge, Polly Pen, Merle Louise. (Archive Michael Colby)

A new generation of Broadway fans has come along, with very different musical tastes. Do you think the “nostalgic” sound you present can compete – or even reach – a young audience?

By day, I’m a substitute teacher working with middle and high school students. I’ve always had a special rapport with younger generations and generally write musicals that are family oriented. While teaching, I’ve witnessed that while students may lean toward pop culture, they still respond to other entertainment if it’s well done and appeals to emotions (or funny bones). I’ve found that younger audiences who see my shows don’t have to recognize the nostalgic references to respond to the eccentric characters and story-telling. During childhood, my other major escape, beside musicals, was the world of comic books. You can look at characters in my shows (such as the Circus of Voices or the oddball musical performers in Tinseltown) as super-heroes, each with special powers. In Charlotte Sweet, there’s a fast voice, a high voice, a low voice, a bubble voice and a schizophrenic voice (half-man, half-woman) who duets with herself. In Tales of Tinseltown, Ellie can imitate any kind of animal sound, audio effect, or singing style. There are also characters patterned around the novel abilities of Ethel Merman, Gene Kelly, and Mario Lanza. In both shows, you can consider the rising singers equivalent to American Idols.

My aim was to appeal to all generations.

Are there any more Colby shows coming up on disc or DVD?

You can read about my other shows and coming attractions at my website. There’s a CD of my songs, featuring a cast of Broadway veterans, Quel Fromage: 50 Years of Colby. There’s a documentary on YouTube about They Chose Me!, a musical I wrote with Ned Paul Ginsburg on the subject of adoption.

Meanwhile, I’m always open to anyone interested in recording my songs or even, perhaps, one of my other shows. Especially fun would be a complete Ludlow Ladd (for Christmas), Slay It With Music (my other musical composed by Paul Katz; a companion piece to Tales of Tinseltown); or North Atlantic (my award-winning spoof of Rodgers & Hammerstein musicals, composed by James Fradrich). From this interview to God’s ears.