Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

23 September, 2017

Has operetta research shifted gear? One could think so, considering that there are finally in-depth academic studies coming out that go way beyond entertaining, yet unreliable recollections of past glories (the various Robert/Einzi Stolz or Vera Kálmán publications), totally sanitized re-interpretations of the genre that was originally something very different (Richard Traubner’s Operetta), or the very ideologically driven attempts of rehabilitating operetta by glorifying the “Offenbachiade” and bashing Broadway musicals, or anything involving revue elements (Volker Klotz). Not to forget the expansive volumes of Kurt Gänzl’s Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre, written as a one-man-show with all the pitfalls such a pioneering enterprise involves. Here, now, are two very different kinds of books that point in a new direction: Barbara Denscher’s “Werkbiografie” of Der Operettenlibrettist Victor Léon, and Matthias Kauffmann’s Operette im ‘Dritten Reich’: Musikalisches Unterhaltungstheater zwischen 1933 und 1945.

Barbara Denscher’s “Der Operettenlibrettist Victor Léon,” 2017. (Transcipt Verlag)

Considering that Mr. Léon wrote some of the most famous, and celebrated, operettas of all time, including Die Lustige Witwe, Wiener Blut, and Der Opernball, it’s astonishing that the first detailed analysis of his work comes out in 2017 – 77 years after his death in 1940. What stopped researchers before? Was it the prevailing idea that the texts for operettas are trivial and don’t deserve attention, that it’s all about the beautiful music? Does that explain the string of Lehár biographies, and the total absence of Léon books? Marie-Theres Arnbom recently sketched a first Léon mini-biography in Damals war Heimat. Die Welt des Wiener jüdischen Großbürgertums, pointing towards some of the more fascinating aspects that one could study (without doing so herself).

“Damals war Heimat,” the new book by Marie Theres Arnbom.

That job was now undertaken by Barbara Denscher. And an admirable job she did. 500+ pages of facts, facts, and more facts.

Miss Denscher doesn’t focus on Léon’s private life (which would be another book worth writing), instead she describes the genesis of each Léon operetta, quoting from private correspondence, historic newspaper reviews, interviews of the era. The result is a glimpse into the machinations of the operetta business of the late 19th and early 20th century. How did the relatively unknown Léon get in contact with aging superstar Johann Strauss? How did the collaboration with Franz Léhar come about, and why did it stop? What’s the story with Leo Fall and Die geschiedene Frau? Why did the former journalist and editor of a feminist magazine continue to insert feminist issues into all his later operettas, celebrating a free and independent woman as his ideal? And what happened with Léon and his career after the Nazis came to power and Léhar was officially declared the Führer’s favorite composer, with Lustige Witwe as his favorite musical theater work?

Denscher gives the answers to all of these questions, she chronicles the many law suits Léon was involved in, she describes wealth management (“Operette macht vermögend”) and how Léon’s Die gelbe Jacke was turned into Das Land des Lächelns. She describes his “resignation” in the 1930s when his name disappeared from playbills because he was Jewish. She also describes how his younger longterm mistress saved Mr. and Mrs. Léon from deportation: they both died peacefully in their homes in Vienna, when most other Jewish operetta people had been deported, killed, or exiled. Léon was spared that fate.

The young Victor Léon in 1894.

Denscher’s narrative is as matter-of-fact as possible, she avoids emotional outbursts or personal reflections. This book is not about her and why she – working as an ORF journalist – finds Léon or his operettas interesting. She lets the facts speak for themselves. It’s not about re-claiming Léon as a “genius” or his operettas as “masterworks” (which would have been the Volker Klotz approach), she allows the reader to make up his or her own mind. However, she does present so many intriguing aspects about each and every one of the shows Léon wrote, that you will probably want to run out and see performances right away. She is certainly no advocate of any nostalgic retro-operetta style, instead she points towards the modern elements, even (and especially) in shows such as Wiener Blut.

Cover of the DVD version of “Wiener Blut” starring Ingeborg Hallstein and René Kollo. (Photo: Deutsche Grammophon)

It’s a perfect antidote to the Richard Traubner narrative. Or film version such as the one starring Ingeborg Hallstein and René Kollo. Which makes it all the more sad that this book is currently only available in German. It deserves an English edition so as to reach a wider audience and enhance the overdue debate in the English speaking operetta world, too.

The book includes a list of all performed stage works by Léon, starting in 1878 with the “Lustspiel” Falsche Fährte (premiered at Vienna’s Sulkowsky-Theater), followed by “Vaudevilles”, “Possen”, “Volksopern” (Edelweiß, 1891), “Operetten”, “Schwänke”, “Zeitbilder” (Gebildete Menschen, 1895), “Ballett-Pantomimen” (Struwwelpeter, 1897), “Operas” (Der polnische Jude, 1901), “Volksstücke” (Fräulein Lehrerin, 1905). The list ends with Fürst der Berge 1932, premiered at the Theater am Nollendorfplatz in Berlin, music by Franz Léhar.

Matthias Kauffmann’s “Operette im ‘Dritten Reich’.” (von Bockel Verlag)

If Denscher’s book ends with the government take-over of the Nazis, Matthias Kauffmann’s 450 page book starts there. It takes a close look at the complicated operetta situation of the era, and tries to make sense of the often contradicting statements. Kauffmann’s main claim is that there is no such thing as “the” Nazi operetta. The musical comedies that were performed between 1933 and 1945, and those that were newly created during that time, differ so much that it’s hard to make general statements that apply to all works.

His book is divided into three sections. First he discusses the idea of an “Un-German Operetta”, describing the new racial ideals the operetta world was confronted with, the “cleansing” of this operetta world of “Jewish” and “Bolshevik” elements, and the new function of operetta as an “enclave”, a safe space for relaxation in turbulent times. (Of course such a positioning and function of the genre is highly problematic, and anything but safe.)

Scene from “Melodie der Nacht,” 1939. (From Matthias Kauffmann’s “Operette im ‘Dritten Reich’.”)

Part 2 describes the many attempts of new and remaining German operetta composers to fill the gaps created in the repertoire by the exodus of Jewish authors. What “substitute” operettas were written and by who? What were the (political and musical) aims of these operettas? How was eroticism and sexuality treated, key elements of operetta pre-1933? How were “traditions” revived and newly created, traditions that in many cases lived on long after the Nazi regime came to an end?

Part 3 looks at the practical consequences of all these ideological debates. The subchapters have headlines such as “Erotik”, “Exotik”, “Starkult.” Kauffmann looks closely at the Heinz Hentschke revues and operettas at Berlin’s Metropoltheater, he analyses how the “American Revue Aesthetic” influenced these shows, and he searches for open and hidden “propaganda” in these shows.

Dostal’s copy of “Gräfin Mariza”: the ultra-Hungarian “Ungarische Hochzeit” from Nazi times.

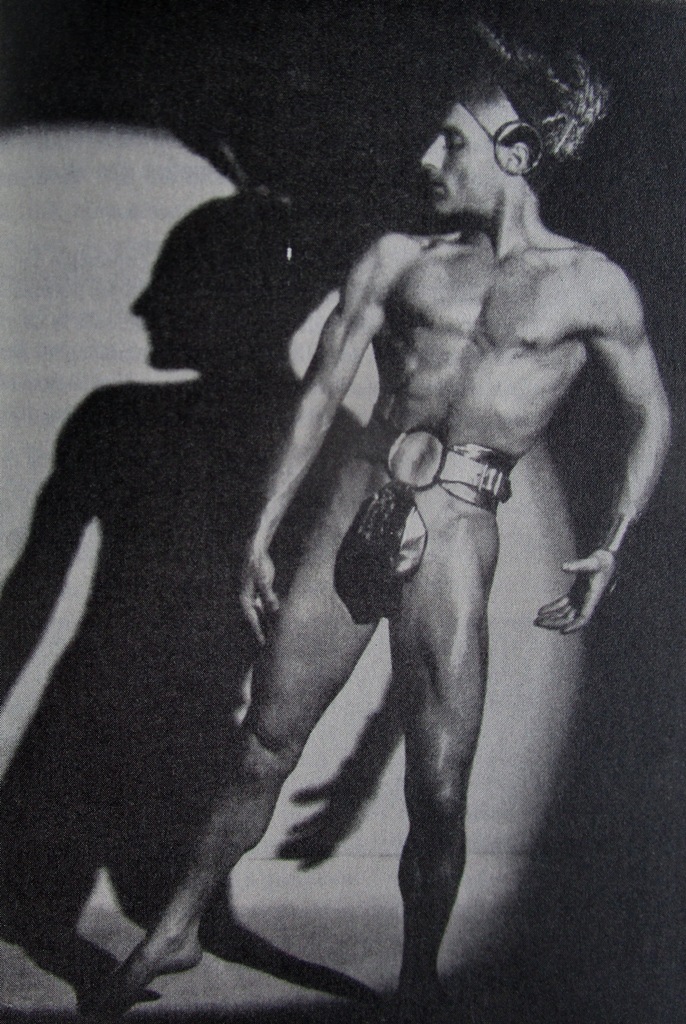

There are many instances where I personally would contradict Kauffmann, but I believe it is important that he has made his statements to open up an overdue discussion. To give you an example: Kauffmann claims that it’s not true that “sex” was eliminated from operetta in Nazi times, making it a “chaste” or “morally restricted” genre, as compared to the liberated way operetta had embraced (and used) sexuality in the decades before. Kauffmann presents, among other things, a photo of the “erotic solo dancer” Alberto Spadolini (what a name!) who appeared in Georg Jacoby’s production of Die Lustige Witwe at Berlin’s Admiralspalast in 1940. His half-nude picture was included in the program brochure, and it’s included in Kauffmann’s book.

Alberto Spadolino in the Georg Jacoby production of “Die lustige Witwe,” 1940. (Photo from Matthias Kauffmann’s “Operette im ‘Dritten Reich’.”)

As is that of “nude dancer” (Nackttänzerin) Agnes Agun in Melodie der Nacht, 1938. Kauffmann compares these nude and erotic dancers to the famous revues and operetta revues of the 1920s, the Erik Charell spectacles at Großes Schauspielhaus or James Klein’s undressed entertainments at Komische Oper. But his comparison stays on the surface. Because in the 1920s, such omnipresent nudity was a sign of revolution, of overthrowing old moral standards. (Just as Hortense Schneider’s nudity in Belle Hélène in the 1860s was a provocation and an outrage, a boycotting of norms and the dawn of a new era; at least I would interpret it as such.)

Agnes Agun in “Melodie der Nacht,” 1938. (Photo from Matthias Kauffmann’s “Operette im ‘Dritten Reich’.”)

There are even statements by Charell explaining why “the world has become naked” – for women and for men! In these shows, which included an updated Merry Widow for Fritzi Massary which was overflowing with newly inserted sexual innuendoes (“Mein Freund aus Singapur”), comparable nudity and sex were a natural and fully normal (for the times) element. They represented the new Zeitgeist of the 1920s.

By Jacoby put Mr. Spadolini onto the stage as an exotic “heroic” hunk to please the eye of the ladies in the audience (the German “heroic” men were mostly at war). Spadolini is not an integrated part of the show. He’s an ornament, a brief reminder of what once was standard and has now become the exception. Mere decoration. And unlike operetta in the times of Offenbach or even Charell, you were not to assume that Mr. Spadolini could be picked up at the stage door for a night of fun. Or can you imagine him receiving visitors à la Hortense in his dressing room, showing them what’s under that frightful XXL ‘chastity belt’ and demonstrating what “Lippen schweigen” can mean in times of fascism and the new military partnership Italy/Germany?

“The Dressing Room of Hortense Schneider,” 1873. Painting by Edmond Morin.

The “sex” the Nazis supposedly put into operetta was a chaste flirting with former glory that had become a joke, everyone knew that nothing would ever happen. You can look at Mr. Jacoby’s film adaptation of Suppé’s Gasparone (with Jacoby’s wife Marika Rökk) and watch how Johannes Heesters verbally flirts with Edith Schollwer as Countess Carlotta Ambrat. If you take the words at face value, he’s seducing her – but if you hear Heesters say them, you realize that nothing will ever happen. It’s indeed a “safe space” where seduction is only hinted at, no one needs to be afraid of anything ever actually happening. That is a fundamental difference between operetta pre and post 1933.

But all of this does not make Matthias Kauffmann’s book less valuable, on the contrary. It’s a long overdue study with many wonderful images from newspapers and program books. He also includes a full list of all German language operetta world premieres 1933 to 1945, starting with Akrobaten des Glücks (music by Walter W. Goetze), Ännchen von Tharau (Heinrich Strecker), Clivia (Nico Dostal), and Die Dame mit dem Regenbogen (Jean Gilbert) … they are in alphabetical order. Ending with Vorsicht, Diana! (Ludwig Schmidseder), Wiener Bonbons (Ferry Zelwecker) and Die zerrissene Venus (Hans Naderer), all in 1943. There are also facsimilies of lists such as Zur Statistik der Operetten in der Spielzeit August 1935 bis Juli 1936: at the top of the list there‘s Johann Strauss with 2,532 performances, followed by Léhar (2,410), Kollo (1,394), Millöcker (1,136), Raymond (863), Goetze (829), Künneke (771), Zeller (699), Stolz (587), Suppé (512), Dostal (495) ….. The list also includes Emmerich Kálmán with 224 performances, and Strecker with ony 157. The fact that Strauss leads the list shows, among other things, what new “traditions” were created in Nazi times.

This book is a valuable continuation of what Boris von Haken started with Der “Reichsdramaturg: Rainer Schlösser und die Musiktheater-Politik in der NS-Zeit, and the more ‘popular’ approach taken by editor Wolfgang Schaller in Operette unterm Hakenkreuz (both published in 2007).

Matthias Kauffmann also offers a general survey of what operetta literature is out there right now, and he clearly states the different opinions in circulation without ever denouncing anyone. Instead, he invites academic discussion.

And that is something that’s been too absent from the genre for far too long!

Let’s hope that the English speaking operetta world will join this discussion soon. The fact that there will be a conference on Gaiety, Glitz and Glamour: Reawakening the “Silver Age” of twentieth-century Operetta in London in October 2017 can be seen as a positive sign. With many German and Austrian researchers delivering papers in English, among them Tobias Becker and Judith Wiemers.

How did an operetta by Jewish Jean Gilbert slip in there?

How did Kalman, Jessel and other slip in there? Read the book. Mr. Kaufmann explains it very well.

Je suis le neveu de Alberto Spadolini. Je voudrais vous envoye en livre sur Spadolini.