Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

25 November, 2017

If you like your operettas exotic, grand, over-the-top and as a total blast, you will probably love the overture to Nico Dostal’s Prinzessin Nofretete. As conducted by Stefan Klingele with the orchestral forces of the Musikalische Komödie Leipzig, you could be made to believe that one of those extravagant Egyptian themed blockbusters is about to unfold – comparable, at the very least, to a Cecil B. DeMille movie or Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra. It’s a cinemascope sound experience with swirling violins, heavy brass, epic chords piled up, interrupted by Aida-like quirky dance movements, and a full set of oriental drums. Think Kismet meets operetta, with Verdi instead of Borodin thrown in. It’s a show that premiered at the opera house of Cologne, Germany in 1936, in the early years of Nazi dictatorship and the years of defining a new operetta ideal that was supposed to substitute the previous ‘degenerate’ works by Abraham, Oscar Straus & Co.

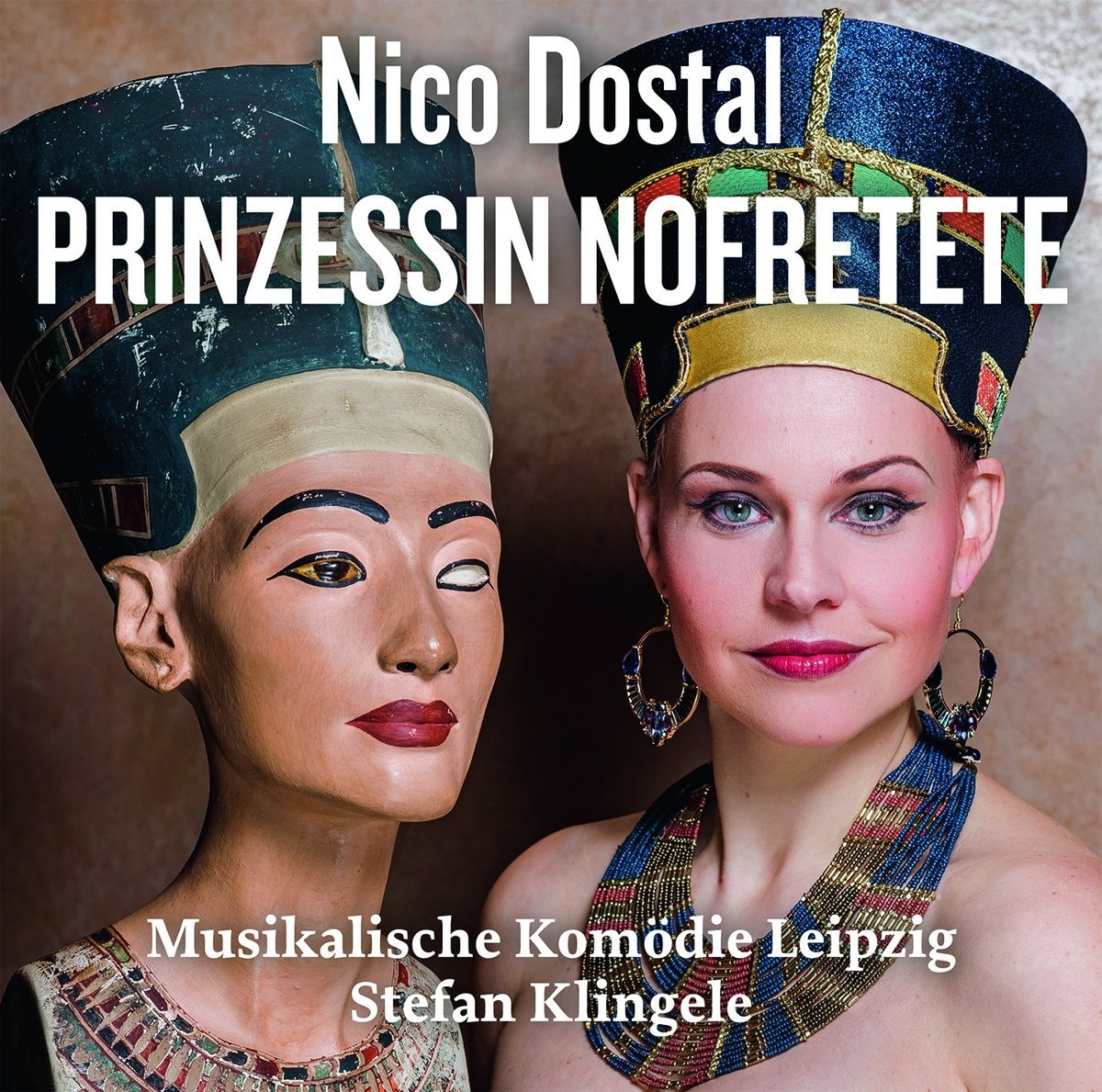

The cast album of Dostal’s “Princessin Nofretete,” from the Musikalische Komödie Leipzig.

The Musikalische Komödie dug up this Dostal rarity in early 2017 for a full new stage production, and that version is now available as a double disc, with large chunks of dialogue, so you can follow the story concerning a group of tourists – who have booked a holiday package with ‘Cook & Son’ – visiting the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, run by British archeologist Lord Callagan (Milko Milev). While a modern-day love affair develops between Callagan’s vice assistant Dr Hjalmar Ekling (Radoslaw Rydlewski) and Callagan’s daughter Claudia (Lilli Wünscher), there’s also a flashback story revolving around Princess Nofretete (also Lilli Wünscher in a double-role à la Susanne Provence/Princess Laya) and the goings-on at an ancient Egyptian royal court.

Obviously, such a story offers many staging opportunities. Dostal and his co-librettist Rudolf Köller (not named in the booklet or on the CD cover) are not the first to utilize ‘Egypt’: in 1919 there was Anselm Goetzl’s Aphrodite, for example, with dances choreographed by Michael Fokine.

The 1919 “Aphrodite” which ran for 148 performances at New York’s vast Center Theatre.

And there was Oscar Straus with his early 1920s extravaganza Die Perlen der Cleopatra. The latter was recently revived at the Komische Oper Berlin with Dagmar Manzel as the Egyptian heroine – anyone who has seen that staging knows what can be achieved by slipping into oriental drag (and out of it). The Berlin production was a knockout, because it offered breathtaking costumes, dancers, and star quality of the highest magnitude. Manzel especially carried the nonsense of the story and turned it into an unforgettable experience. And as an experienced stage actress, she (and her director Barrie Kosky) knew how to deliver dialogue in a way that makes you want more and more and more, instead of creating a feeling of embarrassment which makes you wish they’d skip over all spoken passages as quickly as possible, and get to the next musical number.

That’s what sort of happens in Leipzig. You can already guess what’s coming in the opening track: before the overwhelming overture starts, there’s a short spoken intro by a tour guide. The way these words are delivered are an unpleasant reminder of the many 1970s and 80s operetta recordings with people who might possess pretty voices, but have never had any dialogue training, which makes the jokes seem lame and labored. Here, this is also true for the dialogue that follows later. On the other hand, I am glad that the dialogue is included because it makes it possible to follow the plot’s twists and turns.

Lilli Wünscher as Nofretete and Radoslaw Rydlewski (as Amar) in “Prinzessin Nofretete.” (Photo: Ida Zenna)

It’s a typical Nazi-times operetta: a tale of maximum harmlessness. The sexual undercurrent of Oscar Straus and his librettists Brammer & Grünwald has been eliminated. Instead, it’s a new ‘Aryan’ or ‘proper’ humor that has given German humor in general such a bad name. The women have to be chaste and faithful, once more, and instead of independent strong women you get ladies looking for men to boss them around, while they stay at home and take care of the kids. You could call this reactionary, even if the political message is wrapped into Aida costumes. By comparison, Aida and Amneris are early feminists.

So what about the music? It shifts, effectively, between bombast and easy shuffle-along songs. Ideally, you would need a group of character actors/singers to make the various layers of the story come alive. Here, everyone sounds more or less the same, and very operatic. This works okay in the lyric moments, but no one on this cast album seems to be capable of easily moving between ‘big sing’ moments and casual ‘Schlager.’ Certainly not Lilli Wünscher in the title role, a part originally written for Dostal’s wife Lillie Claus. Wünscher posseses an attractive soprano, but doesn’t come across on disc as an interesting personality. And her partner Radoslaw Rydlewski as Dr Hjalmar Eklind lacks sensualness in their big love duets (“Einmal nur…”). And those duets are sensual; Dostal knew how to show off his wife’s glamorous talents. And he was a master orchestrator.

Radoslaw Rydlewski (Dr. Hjalmar Eklind) and Lilli Wünscher (Claudia) as the ‘modern couple’ in “Prinzessin Nofretete,” at the Musikalische Komödie Leipzig. (Photo: Ida Zenna)

If the ‘heroic’ leading couple is not exactly on the Cecil B. DeMille side of things, the comedy team of Nora Lentner (as Polly Miller) and Jeffery Krueger (as Totty Tottenham) are not exactly the Marx Brothers or Sisters either.

The piece offers many interesting aspects, e.g. using British characters to create the illusion of internationality in the year of the Olympic Games in Berlin, and as a mild comedy of manners. It’s always easier to laugh at others instead of yourself, here the laughs are on the stiff and silly English archeologists and their elderly family members (Angela Mehling as Aunt Quendolin Tottenham). Also, the way people from Northern Europe are portrayed in opposition to the Egyptian locals is a fascinating aspect of the show, from our post-colonial perspective much could be studied here. Stage director Franziska Severin in Leipzig seems to be only minimally interested in that, however. Some operetta fans will be thankful for this, making the musical enjoyment easier for them. That is, if you enjoy harmless operettas drained of all the genre’s original subversiveness.

Nora Lentner (Teje) & Andreas Rainer (Prinz Thototpe) in “Prinzessin Nofretete.” (Photo: Ida Zenna)

Large parts of the music – which is excellently conducted by Stefan Klingele – sound reminiscent of other music. That doesn’t have to be a bad thing, since operetta from the beginning and since Offenbach’s day has been about recycling. Here, the recycling is not a question of parody or ironic comment, but simply the way operetta operated in Nazi times. Beloved older shows had to be replaced, and Dostal was one of the people who did this with great personal profit.

Nico Dostal always claimed to never have been involved with Nazi politics, a claim everyone has repeated without questioning it, ever. Not even Volker Klotz in his slim book Nico Dostal (1995). For a more critical evaluation of the composer, you might want to check Klaus Riehle’s brand-new Herbert von Karajan book. If you wonder what Karajan has to do with Dostal…. you’ll be surprised. Mr. Riehle told me, in a recent telephone conversation, that he had spoken with many people who met Dostal in Italy at the end of WW2 and testified that Dostal was anything but apolitical. Sadly, that information has not entered the Karajan book on a larger scale. It would have been a valuable addition to the current re-evaluation of operettas 1933-1945, as undertaken by Matthias Kauffmann in Operette im Dritten Reich (2017). The shows themselves give ample testimony of the political background, too, even if Leipzig’s dramaturg Christian Geltinger puts the focus of his informative essay in the CD booklet elsewhere. Maybe he doesn’t want to get too political in a region of Germany making headlines with ultra right wing demonstrations.

Lilli Wünscher (Prinzessin Nofretete) and Radoslaw Rydlewski (Amar) in “Prinzessin Nofretete.” (Photo: Kirsten Nijhof)

Compared with Barrie Kosky’s Perlen der Cleopatra and Manzel’s supernova performance, this Leipzig excursion to ancient Egypt sounds a bit (too) tame. Compared with Franz Lehar’s late works in ‘opera’ style, the Dostal score is slightly underwhelming. Instead of Lehar’s glorious tunes and distinct style, (too) much here sounds derivative. Or differently put: there’s too little fun among the dancing mummies.

But Stefan Klingele is certainly a conductor to watch out for. He brings out many amazing orchestral details, he makes the exotic rhythms jump off the page, he holds together the ensembles well, and he’s not afraid to let the big butch march tunes rip, “Ran an den Mann” being one of them. Maybe Klingele should have a serious talk with his casting department, to make future operetta endeavors more convincing. It would be worth it.

Lilli Wünscher as Princess Nofretete at the Musikalische Komödie Leipzig. (Photo: Kirsten Nijhof)

On the whole, I’m happy that productions from the Musikalische Komödie Leipzig are (finally) coming out on CD, distributed by Naxos. After years of uneventful Staatsoperette Dresden CDs, especially of restored Johann Strauss pieces, this is welcome news. The operetta theater in Leipzig is, by all accounts, in a process of change. Selecting shows like Prinzessin Nofretete and Künneke’s Die große Sünderin in 2017 is clear evidence of that; though you might question this focus on ‘Aryan’ operettas. But then again, it’s overdue to re-assess these and discuss their merits. I hope the re-invention of the Leipzig company will move forward quickly, because Kosky can absolutely use competition in that field. For now, Lilli Wünsch as an Egyptian princess is no match for Miss Manzel’s Egyptian queen. And this Egyptian holiday in Leipzig, choreographed by Mirko Mahr, is no match for Otto Pichler’s semi-nude splendor in Berlin. So there’s room for improvement at the Musikalische Komödie. But while that process is underway, we as international operetta fans and CD customers get a chance to broaden our horizon with new titles – even if, sadly, the booklet only offers a short English introduction and plot summery, no English lyrics. Which means non-German speaking listeners must use their imagination; in this case, this might be a good thing!

Because they don’t have to suffer through the ‘humorous’ German dialogue and lyrics such as “Am schönen blauen Nil erwärmt sich das Gefühl…. Wenn man ein Mädel sieht, sofort der Schädel glüht!” or “Jede Frau ist ohne Mann nur ein Fragment, weil sie ohne Mann doch niemals Frau sein könnt.” Current gender warriors would have a heyday to pick this apart, rightly so.

Something that should be said in favor of this recording: compared to the many rarities that have been issued on cpo, mostly recorded at the operetta festival in Bad Ischl, this Prinzessin Nofretete is lightyears ahead in terms of vocal and orchestral quality. So there is hope …