Roland Dippel

Neue Musik Zeitung

1 November, 2021

With the discovery of the opera Leonce and Lena by Erich Zeisl and, now, the first production of Ralph Benatzky’s operetta Der reichste Mann der Welt (The Richest Man in the World) in Germany, Moritz Gogg starts his new position as artistic director of the Eduard-von-Winterstein-Theater in Annaberg-Buchholz with a bang. These discoveries continue the focus on rarities of Gogg’s predecessor, Ingolf Huhn. And just in case you don’t know where Annaberg-Buchholz is: it’s the last subsidized theater bastion in the Ore Mountains before the Czech border. A very attractive place for any operetta tourist to visit.

A scene from “Der reichste Mann der Welt” in Annaberg-Buchholz. (Photo: Dirk Rückschloß / Pixore Photography)

We all know that Ralph Benatzky has more to offer than the plus-sized Im weißen Rössl or intimate successes like Bezauberndes Fräulein. In 1936 he premiered Der reichste Mann der Welt in Vienna, but it disappeared from the stages right after, until it was dug up again in Annaberg-Buchholz in 2021.

First the Nazis and then the kitschy operetta tastes of the post-war years prevented that a work about ugly social realities found their way into the repertoire. Despite the fact that Benatzky wasn’t Jewish (but married to a Jewish dancer), and despite the fact that he triumphed with songs for Zarah Leander as the greatest movie star in Nazi Germany. But Joseph Goebbels didn’t want problem pieces on “his” stages, and later West-German operetta audiences consumed operettas as “pain killers” right up to the 1990s. As did Austrian audiences. So they preferred to put on one saccharine production of White Horse Inn after the other, rather that play Der reichste Mann der Welt.

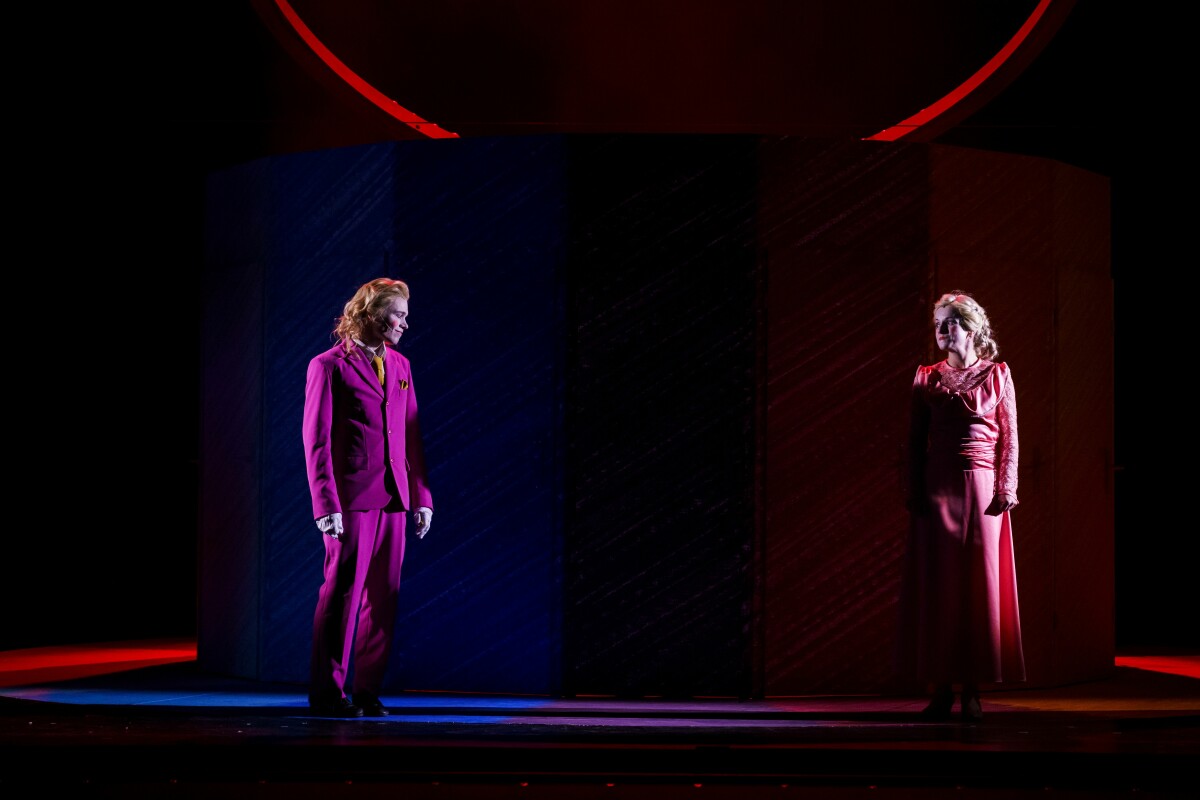

Another scene from “Der reichste Mann der Welt” in Annaberg-Buchholz. (Photo: Dirk Rückschloß / Pixore Photography)

Benatzky and his librettist Hans Müller (who was a famous UFA screen writer and penned the short story on which Oscar Straus’ Walzertraum is based, as well as Lubitsch’s The Smiling Lieutenant) created the central character of Ilka: a wonderfully emancipated woman, who gets close and personal with the banker’s son Schorsch in the sleeping carriage of a train. Even though she despises him, since he was chosen for her by her family.

Benatzky and his first wife Josma Selim in Berlin, in the 1920s. (Photo: Archive of the Operetta Research Center.)

Benatzky wrote concise music that doesn’t just juxtapose various styles from the interwar years but integrates them in a cunning way. There are quotations from Carmen, there’s the Rákóczi March, there’s modern syncopation, and there are typical Benatzky melodies. Some sound like “Gassenhauer” from Berlin, some have a sweet Viennese lilt, but they are always highly individual. And more than mere quotations. “The richest man in the world” – that is the character the impoverished Ilka marries in the end.

However, the story remains in a state of limbo for most of the time, which the Annaberg production makes its central aspect. There are 13 musicians in the pit, together with the company’s new musical director Jens Georg. The orchestrations are by Wolfgang Böhmer and can be called pointed, without sentimentality, and piquant. A piano accompanies the dialogue scene. Also important: the newly created arrangements work well in the over-acoustics of the house. And they never sound overblown, not even when Benatzky juices things up for the big climaxes.

So what’s it all about? Only Ilka’s marriage to a rich man can save the Györmrey family from financial ruin. Any means to achieve such a marriage is deemed suitable. Which is why the family carefully watches every move between Ilka and Schorsch, the extremely wealthy banker’s son who happens to also have bel canto ambitions.

More “Der reichste Mann der Welt” in Annaberg-Buchholz. (Photo: Dirk Rückschloß / Pixore Photography)

Regisseur Christian von Götz saves this standardized operetta construction from becoming tiresome. He doesn’t care about the plot, but he is interested in the situations that emerge, and the punch-lines-with-music these situations offer. He also emphasizes the various tender moments. And he’s assisted greatly by choreographer Leszek Kuligowski. Together, they make movement and looks more important than lines in the libretto.

As a result, Der reichste Mann der Welt turns into a celebration of the coexistence of different ethnic groups and religions. Schorsch-the-tenor discovers that his future father-in-law was once a “Kammersänger”, and the Viennese dialect mixes with Hungarian accents and Yiddish. The costumes are in all the colors of the rainbow, representing a multi-layered and diverse entertainment industry destroyed by the Nazis. Of course, the rainbow also has a poignant queer meaning.

Rainbows all over in “Der reichste Mann der Welt” in Annaberg-Buchholz. (Photo: Dirk Rückschloß / Pixore Photography)

On stage, there’s a circle of revolving doors, with colorful light bulbs above them. Making it look like a carousel that eternally turns and turns. Everything is intensely colored, until at the end the scene turns to a menacing red – a warning of what is to come during the Holocaust, with ash-gray smoke rising up. The stage director uses this moment to make us think, but without destroying the entertainment. Instead, he seems to say: this kind of fun, such jokes, the joy that Benatzky and Müller envision here, all of it is a precious commodity. Something we need to protect and value.

The ensemble, that has had lots of experience in the past with rediscovered romantic operettas, is well versed and manages to pull all the stops out when necessary. Madelaine Vogt as the bride-to-be can appear lovely as Ilka, but only when she wants to.

A scene from “Der reichste Mann der Welt” in Annaberg-Buchholz. (Photo: Dirk Rückschloß / Pixore Photography)

In the case of László Varga, Christina Wincierz and Leander de Marel the characters sometimes disappear (on purpose) behind the punch lines. This is most evident in Richard Glöckner’s attractive Schorsch. The director deconstructs his tenor and the pink suit he wears, and turns the character from a tie-wearing bank assistant into a bird of paradise. The result is not a caricature, but an original new character who sings beguilingly.

The rest of the cast offers gems like Nadine Dobbriner as Juliska, a bumble bee like Marvin George, and Bettina Grothkopf as a society lady. All of their beautiful moments are but fleeting, because the next dance, the next joke and the next hit song are always just around the corner.

The star-crossed lovers in “Der reichste Mann der Welt” in Annaberg-Buchholz. (Photo: Dirk Rückschloß / Pixore Photography)

The bottom line is this: the smallish company in Annaberg-Buchholz is participating in the current operetta renaissance on an exhilaratingly high level. And they are offering an important rediscovery that deserves to be seen and taken note of.

For more information and future performance dates, click here. Mr. Dippel’s original Germany language review can be found here.