Laurence Senelick

Operetta Research Center

25 June, 2022

La Grande Duchesse de Gérolstein was, arguably, Offenbach’s first truly transglobal success. It benefitted from opening during the Exposition universelle in Paris in 1867 and the consequent attendance of crowned heads and eminent statesmen. With the beguiling Hortense Schneider as the libidinous duchess and a plot which drew on current European politics, it ran for 200 performances.

Its music, dialogue and even costumes became familiar to the public at large, and by the end of the century had played everywhere from Salt Lake City to Yokohama. Often it served as the wedge to insert Offenbach into unfamiliar societies, first via French troupes and then in the local language.

Offenbach’s “Grand-Duchess of Gerolstein” in Japan, in the 19th century. (Photo from Laurence Senelick’s “Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture”, Cambridge University Press 2018)

Parody was often the medium used to facilitate this introduction.In his authoritative book on Offenbach in Spain, Portugal and Italy, Jacobo Kaufmann reports that the first Offenbach opera to be staged in Italy was Monsieur Choufleuri restera chez lui… at the Teatro Re in Milan in April 1865. It was performed by a French company managed by Eugène Meynadier, who followed it with three more short operas.

The exterior of the Teatro Re in Milan, 1860, as seen by Luigi Cherubin.

By 1870 opéra bouffe was well established in Milan and Meynadier had presented some of Offenbach’s full-scale works, among them La Grande Duchesse de Gérolstein, rapturously received; La Princesse de Trébizonde and La Périchole. The following year, Kaufmann reports, a parody entitled Il Gran Duca di Gerolstein was staged. He calls it “the first incursion in the Offenbach repertoire in an Italian idiom.”[1]

Kaufmann was right to be cautious in his phrasing. Il Gran Duca was in fact El Granduca for the three-act comedy was written largely in the Milanese dialect, with occasional passages and songs in standard Italian. It was, in fact, a corner stone in the establishment of a Milanese-dialect theatre.

THE AUTHOR

The play’s author Cletto Arrighi (an anagram of Carlo Richetti, 1830-1906) had been involved in the first war of Italian independence (1859-61). An autodidact, Arrighi soon gained a reputation as a radical satirist and politician.

Author Cletto Arrighi.

Italy still chafed under the rule of the Hapsburgs in Vienna, and an anti-clerical, anti-establishment climate was distilled in Arrighi’s works. In his first novel he had launched the term “scapigliatura” (disarray, non-conformity) and popularized the concept in his most famous novel La Scapigliatura e il 6 febbraio (Dissipation and February 6) (1862).[2] There he defined it as the temperament of rebels and malcontents; his heroes, given to drinking and gambling, and scorning social conventions.

In all the great cities of the civilized world there is a certain class of people, between twenty and thirty-five, no older, almost always full of wit, more advanced than their era, independent like the eagle of the Alps, apt for both good and evil, restless, tormented, turbulent … This class, true pandemonium of the age, the personification of carelessness and insanity, arsenal of disorder, the spirit of independence and opposition to established orders. I have christened this class, which has in Milan, more than anywhere else, a reason for existing with the nickname of Scapigliatura. [3]

The term became the equivalent of the French Bohème. A scapigliato movement, anti-bourgeois and anti-romantic, soon took deliberate shape. It could it say with Groucho Marx, “Whatever it is I’m against it.” The movement found a sympathetic medium in Offenbach’s anarchic and irreverent operas. One local critic suggested that if Milan had theatres dedicated exclusively to opéra bouffe and audiences refrained from formality, an Italian variant could be created. “But, to make funny parodies and sparkling and elegant music, spirited poets are required, and teachers endowed with a lot of verve and a lot of culture.” [4]

Arrighi was ambitious and desired a more ample repertory of “irregular” or foreign works that would have a great appeal for a local audience. In 1869 he founded what is considered the first Milanese-dialect theatre. The following year he fitted up the Padiglione Catteneo (Cattaneo Pavilion), a former furniture store turned café chantant, with a proscenium stage and collected a permanent company, supplying much of the repertory.

The Duomo in Milan. (Photo: Michele Bitetto / Unsplash)

Of his thirty-nine comedies and comic operas, his best El barchett de Boffalora (Buffalora’s Boat, 1870) and On milanes in mar (The Milanese at Sea, 1875) displayed great originality. [5] In his promotion of a vernacular drama, Arrighi has been compared with Dario Fo.

THE PLAY

Arrighi’s comedy is not an organic opéra bouffe. Its music is incidental – short songs and choruses, fanfares, offstage ballroom tunes -, supplied by Enrico Bernardi (1838-1900), an experienced opera composer (a Don Pasquale of his own was performed in Trieste in 1868).

The plot and dialogue smack less of Meilhac and Halévy than of Gilbert and Sullivan. Indeed, the device of a theatrical troupe taking over the court of an impoverished duchy would later serve as motor for their own Grand Duke (1896). [6] The dialogue teems with anti-Prussian remarks and ridicule of international politics generally. The characters of lesser rank speak Milanese, while the nobles and foreigners converse in formal Italian. Early on the Grand Duke tells his majordomo, “Speak your dialect which pleases me more than bad Italian; I too know how to speak it.” [7]

Act One opens in the music room (sala di studio) of the Palace, for the Grand Duke is as crazy about opera (and court etiquette) as his aunt, the late Grand Duchess, was about men. He does nothing but sing and stage ceremonials. Representatives of the music publishers Ricordi and Lucca are dunning the majordomo Ambrogio for the rental fees for scores. He shows them that the ducal treasury contains only twenty centesemi, for Offenbach’s Grand Duchess spent much of it and her nephew squandered the rest. Ambrogio returns the scores to them and they depart.

Wilhelm Jaeger in the Viennese production of Offenbach’s “Die Großherzogin von Gerolstein.” (Photo: Fritz Luckhardt / Theatermuseum Wien)

The Grand Duke enters, musing over whether a certain motif appears in one opera or another. Given his impoverished circumstances, without even tobacco in his pouch, he decides to abdicate. Ambrogio reminds him that Gerolstein is under the protection of both England and Russia. The Duke is in love with Guglielmina, the sister of the Margrave of Assia-Cassel. Ambrogio points out that if he can persuade the Margrave to give him the hand of his sister and her dowry of six millions, all will be well. The Duke responds that, humiliated by his impoverished state, he is leaving precisely to avoid an imminent visit from the Margrave and his sister, he begins packing, his scepter with an umbrella, his armor with his winter overcoat.

At that point, a Milanese manager of an opera company, Giuseppe (Peppino) Barbagoli, is announced. When he was rich and powerful, the Duke had signed a contract with his old acquaintance and the troupe is now at the door. (Imagine that Hamlet had been the one to invite the players to Elsinore.) When he finds that the contract for the performance will not be honored, Peppino asks for the court regalia in recompense to swell his costume wardrobe, but even that is gone, along with the courtiers and the army. Peppino comes up with a scheme: the lead singers and the ballerinas in his company will stand in for the court. He claims that his prima donnas are capable of fooling any ambassador. When the Duke frets about court etiquette, the manager points out that his aunt, Offenbach’s Grand Duchess, had few scruples about such things. The Duke consents, tells Ambrogio to unpack, and orders them to issue decree upon decree.

Peppino questions the majordomo about the state of the army. Only 38 or 39 men are left, not counting the band, while nothing remains of the national guard but its banner. The cavalry consists of one donkey and one hack; the only vessels are not ships but beer steins. The next day the ambassador of the republic of San Marino is due to arrive to conclude an offensive-defensive alliance. [8]

The soldiers, increased by 12 chorus members, will escort first the ambassador and then the Margrave. As the opera company gathers in the next room, the Grand Duke appoints Peppino a kind of Pooh-Bah avant la lettre:

You shall be Prime Minister, secretary of my privy council, grand master of court ceremonials, minister of useless affairs and superintendent of my lesser pleasures. Would you like to be Minister with or without portfolio?

Barbagoli. It’s all one to me. Without portfolio. The little a minister makes can be put into a pocket. (Act I, scene 6, p18)

He’s also made Marchese de Viarennenburg with a chestful of medals, since he was born in the Milanese district of Viarenna.

Act Two takes place in the throne room where Peppino is instructing his leading players and calling them by their new names. Morfeo the baritone is now Marquis de Cassina di Pommestein, the prima donna Sofia is Countess of Sedrianisburg. Adelia, who is the lover of the tenor Pompeo, when asked how she’ll manage if asked about politics, sings a ditty whose burden is “Always say I know nothing!” (Me ne intendi propri nient!) (Act II, scene 2, p21). The men, on the other hand, are advised to speak of the crown, politics and diplomacy in pompous terms, assuming serious miens but doing nothing.

The Grand Duke inquires about the crowd that is to applaud his speech from the Throne. Peppino assures him that it will be conducted by their bandmaster. In a long aria, the Duke explains that, given the exigent circumstances, diplomacy must be the chief weapon against the ambassadors, using palaver that proves black is white. Ambrogio explains to Peppino that the Prince of Wales is the Grand Duke’s rival for the hand of the Margrave’s sister and her dowry. The English ambassador has been sent to grease the wheels; his wife, born in Paris, is beautiful but crafty as a fox. Peppino decides not to admit them, but the majordomo insists that court etiquette demands the ambassadors be received in order of importance.

As the appropriate fanfare is played and a series of tableaux unfolds, Lord Chifferposs and Lady Elisabetta Codeghinton-Chifferposs are announced, followed, sequentially, by Tiraspaghi, ambassador of the Republic of San Marino; the Grand Vizir Aly Baba Pipi Cocò, ambassador of the emperor of Morocco; and, last and consequently least, his serene highness the Margrave Federico Guglielmo and mademoiselle Berta Gugielmina Ostava d’Assia Cassel. (On her entrance, the Duke hides.)

Peppino in turn introduces his actresses as noblewomen, and the Margrave takes an instant liking to Adelia (the so-called Marchese di Gorgonzolikoffen). A page passes around gelati and sorbets, and the theatrical guests fall on them avidly. The Margrave and the English try to get a straight answer out of the Prime Minister.

Margrave. What do you say, Marchese, to the great question?

Peppino. Ah, the great question! (What on earth is that question?) Listen…it strikes me that the great question differs greatly from the small one.

Margrave. (He doesn’t want to be pinned down!) Look here, as his Highness’s Prime Minister, whose defense would you undertake?

Peppino. Defense? I’m of the opinion that it’s always best to be friends with both sides as much as possible.

Margrave. (What a fox!) (Act II, scene 10, pp.27-28)

This kind of verbal fencing goes on for some time (as Chifferposs says, “like the school of the great Machiavelli”) until Adelia declares that the music for the ball has begun and offers her arm to the Margrave. Then Peppino exchanges gibberish, reminiscent of the Turkish pageant in Molière’s Bourgeois Gentilhomme, with the Moroccan ambassador (“He’s talking Arabic” which must be “a lot like Milanese”). They go to the ball, singing nonsense syllables.

Adelia, in her attempt to persuade the Margrave to give his sister to the Grand Duke, has managed to make him smitten with her. She will yield to him only if he complies with her request, which he claims is impossible. The Prince of Wales is inflexible and the Chifferposs couple want the contract signed at once. Chifferposs meanwhile cannot find his wife, but states that “dissimulation is the great secret of diplomacy.”

When Peppino tells him there’s a plot afoot, the Englishman insists on his inviolability. However, the intrigue relates to his status, not as a statesman, but as a husband. His wife is about to have a rendez-vous. Indeed, when they leave, Elisabetta enters. She is far from persuaded by the ridiculous courting of “the poor colonel with his phrases from opera librettos” (the tenor Pompeo), but leads him on because she is jealous of the Marchesa di Gorgonzolikoffen (Adelia). Pompeo woos her with flowery phrases; when he compares himself to Prometheus bringer of fire she suggests rather Morpheus bringer of sleep. (Pompeo assumes she means the company baritone Morfeo.) Chifferposs sees him take her hand but avers he will dissimulate.

Advances to Adelina have also been made by Aly Baba who has told her that when you wear your turban you must never wash your hands in the morning and must be nasty to ladies. Chifferposs is outraged that the vizier wishes to go through the door ahead of him, but Peppino insists that court etiquette demands it. Then he tells the Moroccan that etiquette requires the Englishman to go first. The act ends with the two ambassadors in the doorway doing an Alphonse-Gaston routine: “You first, no, you first.”

As Act Three begins, the ambassadors have been in the doorway for twelve hours, undesirous of transgressing etiquette. They fall dead asleep onto a sofa. Pompeo tells Peppino he’s about to run off with the British ambassador’s wife. He promised her a regimental escort (the mule and the nag). She wrote him a love-note to say that life with her husband has become intolerable and she’s willing to be abducted. A carriage is at the door, ready to take them to Paris. They are to depart in ten minutes, but Pompeo hasn’t had time to alert Adelia.

When Pompeo leaves, the Margrave reveals that he is love with Adelia; he inquires of the Grand Duke her social standing but the latter demonstrated a certain hesitation. However, the Margrave explains that he is “very indulgent to sins of love.” “Everyone knows that the famous Grand Duchess of Gerolsein, the aunt of our Grand Duke, was a lady of very easy virtue, very capricious.” (Act III, scene3,p.41). So the Grand Duke suggests that Adelina, though illegitimate, has princely blood in her veins. Her lover was the triangle player in the court orchestra. Now the Margrave intends a double wedding: if the beautiful Marchesa agrees to marry him, he will break his contract with the Prince of Wales, dismiss Lord Chifferposs and bestow his sister on the Grand Duke. If the Marchesa refuses, the contract will be honored. The Margrave sent her a note to meet him at noon for her answer.

Peppino figures that if Pompeo runs off with the English lady, he can persuade Adelia to accept the Margrave. Then Aly Baba informs her that the emperor of Morocco wants her; curious to know if she’ll be his only wife, she begs time to reflect. “Bear in mind that marrying a Turk is not like ordering a coffee.” There follows a duet between Pompeo and Adelia professing their doubts of one another’s love; it becomes a trio when Peppino reconciles them with his “diplomatic” suggestions.

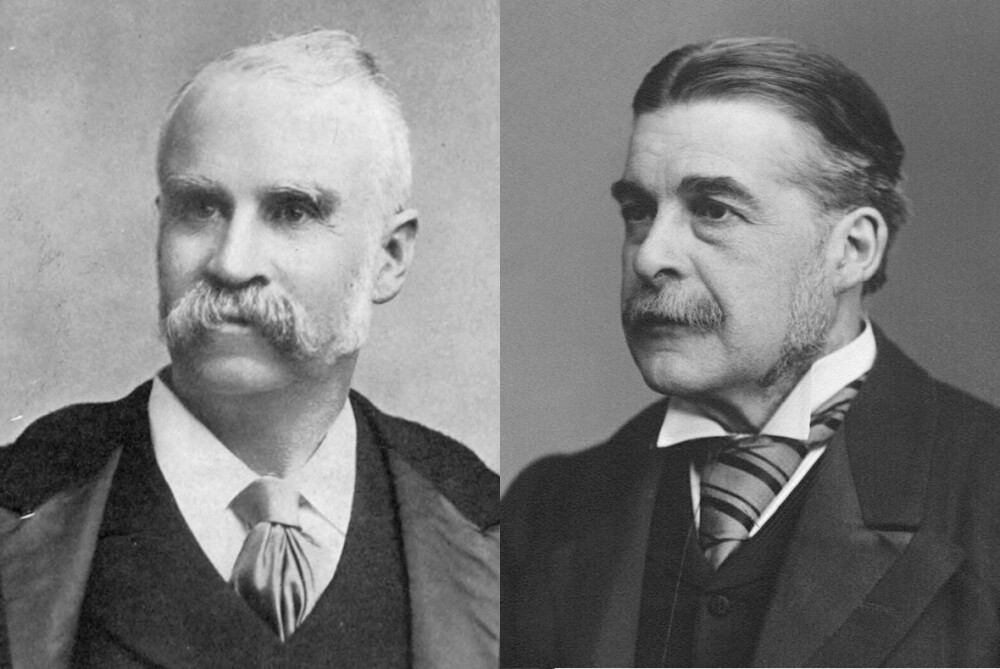

The Margrave presses his suit, emphasizing that the Grand Duke’s marriage to his sister depends on Adelia’s favorable response. She insists he promise first and then protests she didn’t realize he meant marriage. She confesses that her cousinship with the Grand Duke is false: the Grand Duchess’s illegitimate baby died and Adelia, “of ignoble extraction,” was substituted. More shades of Gilbert and Sullivan!

The team of Gilbert (r.) and Sullivan. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Despite this sensational revelation, the Margrave insists on marrying her. She then reveals that her father is a poor old man who patches torn shoes (le scarpe rotta). “Tell me at least he was a shoemaker.” Not even a maker of shoes (calzolajo), she replies, but a mere cobbler (ciabbatino). Even so, the Margrave swallows his ancestral pride and is willing to marry a cobbler’s daughter. Whereupon Adelia uncovers yet another state secret: she is secretly married to the colonel of cuirassiers Count di Barlassinembeg (i.e., Pompeo). Even this does not faze the Margrave who is aware (informed by a letter from Peppino) that the colonel has fled with Lady Chifferposs.

At this juncture Pompeo arrives with a dispatch announcing that Lord Chifferposs and his wife are leaving at once for England. Stunned by so many “plots against me,” the Margrave gives in, asking only that his sister never be told the truth. He assures the Grand Duke that, now in possession of two little state secrets, he can announce the ducal marriage to the Margravine Guglielmina. The play ends in a chorus renouncing politics.

THE AFTERMATH

According to the Italian press, The Grand Duke of Gerolstein enjoyed “an exhilarating success.” [9] Foreigners were not so easily impressed. A French critic reported that “the parody is very lackluster (terne), the music rather vivacious but unoriginal and remains a hundred leagues below Offenbach.” [10] One wonders how much of the Milanese dialect was understood by non-locals.

Edoardo Ferravilla photopraphed by Mario Nunes Vais.

Some of the success was due to the brilliant comic actor Edoardo Ferravilla (1846-1916), illegitimate son of the beautiful soprano Maria Ferrari and the nobleman Filippo Villani (hence his stage name). He had made his debut in Arrighi’s company at the Teatro Milanese as a romantic lead and remained there for thirty-two years. Over time he created a whole gallery of dialect characters, sometimes masked, beloved for their fights and lazzi. In The Grand Duke he played the Margrave with “a considerable fake paunch.”[11] In the 1880s and 90s he toured his own company throughout Italy and survived long enough to appear in silent film.

The Grand Duke enjoyed a revival at the Teatro d’Estate in 1872 (31 May 31, June 2, June 4) and then disappears from the bills. [12] Arrighi continued to be prolific as a dramatist, but in later years increasingly catered to the tastes of his audience, distancing himself from the strict program of public enlightenment he had dictated when his theatre was created. He quarrelled with the actors over his management and was eventually expelled from the company. [13]

Meanwhile, under the influence of Zola’s naturalism, he published a sensational serial novel Il Ventre di Milano (The Seamy Side of Milan), a Milanese-Italian dictionary, and a parody of Manzoni’s classic I Promessi sposi (The Betrothed) as Gli sposi non promessi (The Non-betrothed). This was a polemic against every aspect, political, socio-cultural and religious, of Italian life. Unable to find a publisher, he determined to renounce literature. He had continued the disordered private life or scapigliata of his early years, losing vast amounts at gambling (one of the reasons from his expulsion from the Teatro Milanese). In 1902 in the presence of Cardinal Andrea Carlo Ferrari, Arrighi repudiated all the anti-Christianity in his works. Four years later he died in abject poverty.

Cardinal Andrea Carlo Ferrari, Archbishop of Milan.

El Granduca di Gerolstein may have had a fleeting career on stage, but it serves as yet another example of how Offenbach’s work inspired and liberated playwrights and composers in repressive societies to capitalize on their own traditions. The Milanese dialect theatre is only one of the many movements – in Brazil, Egypt, Japan, Russia and elsewhere – that got its kick-start from the opéra bouffe.

Laurence Senelick is the author of Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture (Cambridge University Press).

“Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture” (2018) by Laurence Senelick, together with the ground breaking “Offenbach und die Schauplätze seines Musiktheaters” (1999).

[1] Jacobo Kaufmann, Jacques Offenbach en España, Italia y Portugal (Zaragoza: Libros Certez, 2007), 223. My translation here and throughout. Also see Carlotta Sorba, “The origins of the entertainment industry: the operetta in late 19th century Italy,” Journal of Modern Italian Studies 11, 3 (2006): 282-301.

[2] February 6, 1853 is the date of an armed uprising of the Milanese against Austrian domination. An important event in the history of the Risorgimento, it caught the attention of Karl Marx.

[3] Quoted in Kaufmann, Jacques Offenbach, 215.

[4] Antonio Ghislanzoni, Gazzetta Musicale di Milano, xxi (17 June 1866), quoted in Kaufmann, Jacques Offenbach, 214.

[5] Carlo Righetti (managing director), Il Teatro Milanese. Rendimento morale, litterario e amministrativo (Milan: E. Civelli, 1873); G. Acerboni, Cletto Aririghi e il teatro Milanese (1869-1876) (Rome: Bulzoni, 1998).

[6] The likely origin of this, the last of the Savoy operas, was Tom Taylor’s story “The Duke’s Dilemma,” which appeared in Blackwood’s Magazine in 1853; actors in positions of power was also a prominent theme in H. B. Farnie’s comic opera The Prima Donna and Gilbert and Sullivan’s own first attempt Thespis, or The Gods Grown Old.

[7] Cletto Arrighi, El Granduca de Gerolstein. Commedia in 3 atti (Milano: Carlo Barbini, 1877), Act I, scene 2, p.11.

[8] Something of an in-joke, like referring to the Swiss Navy. San Marino, the only independent city-state left in Italy, is landlocked.

[9]“Teatri,” Nuovo giornale illustrato universale 4, 4 (22 gennaio 1871): 39.

[10]“Italie,” Le Guide Musical 27, 3 (19 janvier 1871).

[11] Edoardo Ferravilla parla della sua via, della sua arte, del suo teatro (Milan: Società editorial italiane, n.d.).Other members of the company who had illustrious careers were Gaetano Sbodio, Emma Ivon, Giuseppina Giovanelli and Edoardo Giraud who made a hit as the painter in Arrighi’s El barchett de Boffalora.

[12] It may have inspiredEn Marchese der Grille by Mascetti (1889), in the Roman dialect.

[13] Arrighi offered a defense of his actions in “Storia del Teatro Milanese (auto-pseudo-apologia [1889],” in Milano Nuovo. Strenna del Pio Istituto dei rachitici di Milano anno X (Milan: Bernardoni di C. Rebeschini, 1890): 39-56.

Splendid piece. Thank you for some real, original research.