Laurence Senelick

Operetta Research Center

8 December, 2022

Offenbach was introduced to the Russian stage when a French company played La belle Hélène at the Imperial Mikhailovsky Theatre in St Petersburg on 9 April 1866. Over the next two years a mania for operetta seized society and private entrepreneurs were eager to cash in on the phenomenon.

The Imperial Mikhailovsky Theatre in St Petersburg today. (Photo: A.Savin / WikiCommons)

However, the tsarist regime held a monopoly on all theatrical presentations in Moscow and Petersburg which would not be lifted until 1882. In the northern capital, the seat of government, the official playhouses were the Aleksandrinsky (Empress Alexandra), which was usually dedicated to drama in Russian, the Mariinsky (Empress Maria) devoted to opera and ballet, and the Mikhailovsky (Grand Duke Michael), which housed French and German troupes and visiting stars.

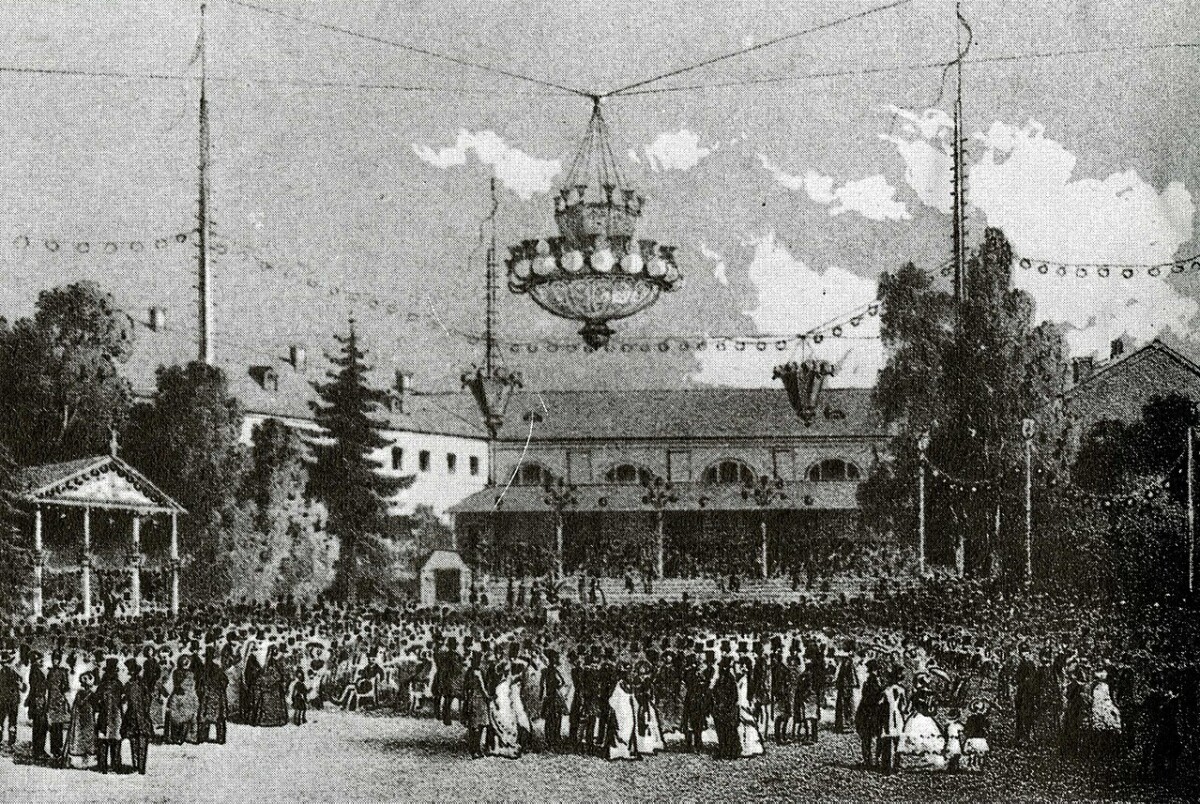

The only privately owned and managed staged entertainments eligible for licensing were fairground booths, circuses and variety shows. Of these, the most popular were the Artificial Mineral Waterworks of the Swiss-born confectioner Johann Luzius Isler, an amusement park aimed at the family trade, and the racy café chantant of the show booth manager Wilhelm Berg. Once the fad for light opera took hold, both Isler and Berg poached performers and songs from the French stage.

Johann Luzius Isler’s Artificial Mineral Waterworks in St. Petersburg, 1852. (Drawing by Vasilii Fedorovich Timm)

Berg had opened his theatre in a long, shed-like building on Nevsky Prospect in the city center in 1866, and it soon became what was known in Paris as a “théâtre à femmes”; although it presented some gifted performers, its prime function was to showcase feminine pulchritude, especially by means of the cancan. The stage was studded with good-looking supernumeraries possessed of neither voice nor talent. Some of them even paid the manager to display them, and might interrupt a performance by “telegraphing” to the male occupants of a box. Berg’s theatre was notorious, but a privy councilor was quoted as saying, “It’s educational, mon cher, for the reasoning powers. I’d rather my son went to Berg’s than hang out with Bazarov, Renan and other nihilists.” [1] It remained active until 1876. The building burned down the following year. [2]

Berg also launched a new enterprise on the site of the former Novosil’tsev circus, built in 1857 and rebuilt after a fire in 1859. (Fires were frequent in timber-constructed theatres lit by candles or gas, but often beneficial in allowing more up-to-date edifices to replace them.) It was “a round wooden building, with a ceiling upheld by metal columns, and a roof of wooden planks, successful from an acoustic standpoint: every word could be heard even in the farthest places.” [3] At first it housed circus acts, and then remained empty for three years.

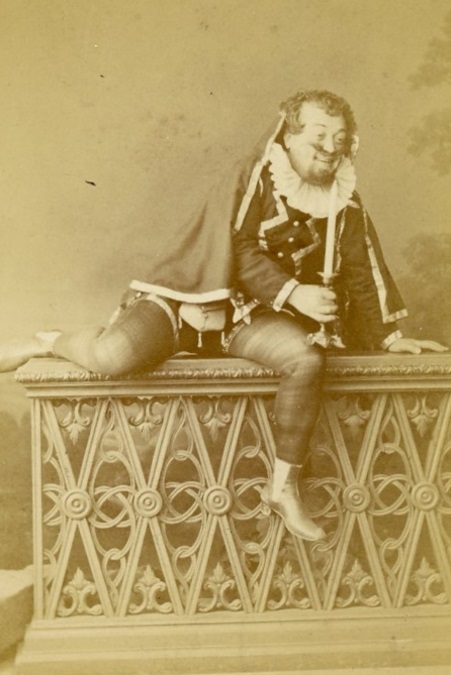

Berg ceded it to a provincial bureaucrat named A. V. Figner who re-opened it as the Teatr Buff (Theatre Bouffe) on 19 September 1870, with the interior redesigned as a formal auditorium. The authorities allowed him to stage productions only in French, German or other foreign languages of non-dramatic and non-integral excerpts from operettas, music, song, magic acts, acrobatic numbers, and Icarian games (juggling the human body). Within those strictures, in Petersburg’s central square across from the grandiose Aleksandrinsky, Figner dedicated his theatre to comic opera. Inexperienced and unimaginative as an entrepreneur, for the first season he invited a French operetta troupe that had been performing at Isler’s Artificial Mineral Waterworks. It was headed by the talented actor and director Joseph Roux. [4]

Joseph Roux as Barbe-bleue. (Photo: Bergamasco, St Petersburg. Collection Laurence Senelick)

Legally enjoined from putting on full-length pieces, Figner, by paying a certain sum to the management of the Imperial theatres, was allowed to perform one-acts such as Les trois écoles. Audiences showed scant interest and attendance was poor.

On 4 January 1871 the insolvent Figner sold out to Vasily Nikitich. Egarev, manager of the amusement park The Russian Family Garden. Egarev, a seasoned impresario with a finger in many pies, decided to spare no expense in attracting the public to the Bouffe and engaged the reigning star of Parisian comic opera. [5]

The Advent of Schneider

Hortense Schneider, a discovery of Offenbach’s, had shot to fame during the Paris Exposition of 1868, playing La Grande Duchesse de Gérolstein. Despite the amorous susceptibility of the Grand Duchess, allegedly based on Catherine the Great, Schneider managed to finesse the more risqué features, “achieving by grace and charm what she refused to exploit by misbehavior.” [6] Her knowing use of innuendo and her own gamy reputation led so many crowned heads to visit her dressing-room at the Théâtre des Variétés, that her sarcastic rival Léa Silly named it “Le Passage des Princes,” leaning on the double entendre of passage. [7] Among the callers were the Tsar Alexander II and his brother Grand Duke Konstantin.

“The Dressing Room of Hortense Schneider,” 1873. Painting by Edmond Morin.

The Franco-Prussian war broke out in July 1870. Schneider, by then a full-fledged international star, served as a volunteer nurse during the Siege of Paris; but was eager to leave France while the Commune raged. Leading French actresses, such as Mlle George and Rachel, had long regarded Russia as an Eldorado, so Schneider signed with the Bouffe for a guest appearance of several weeks, at 1,500 rubles a night.

The French press was alarmed. Le Figaro reported, “Mlle Schneider must be unaware of the wasp’s nest in which she’s been thrust. This theatre is a secondary hall whose regulations authorize only partial performances of works.” [8] Evidently, an agent of Egarev or the diva herself corrected this impression, for a retraction shortly thereafter stated that the theatre is chic, its troupe constituted of excellent voices selected from Parisian venues, and Schneider’s lavish salary guaranteed. [9] She would open in her signature role, La Grande Duchesse.

Hortense Schneider as the Grande Duchesse of Gerolstein. (Painting by Alexis Joseph Perignon)

Since the Imperial theatres also had a monopoly on the names of works they performed, the Bouffe had to come up with alternative but allusive titles. An advertisement such as “The arias, duets and rondeaux of the operetta Le Beau Pâris will be interpreted by…” would lead the public to substitute La Belle Hélène. La Grande Duchesse was an impermissible title for a court rife with Grand Dukes, not to mention her alleged kinship to Catherine the Great. The censorship insisted, moreover, that a title could not refer to a reigning sovereign., so the piece was billed as Le Sabre de mon Père.

Before Schneider’s arrival in St Petersburg on 10 December 1871, all tickets for her performances were sold out. What the Russian public hoped to see was “something more outrageous in its cynicism than anything it had ever seen before, a sort of personification of licentiousness and grivoiserie, taken to the ultimate.” [10] Advance publicity fueled the furore.

By telegraph from Petersburg to Verzhbolov [on the German border] a special train was ordered; bouquets of flowers from all the orangeries in Petersburg were sold out two weeks in advance, jewellers hastened to make a wonderful scepter of diamonds and a series of bracelets, brooches, necklaces; a special deputation was selected to meet the “diva” at the Warsaw station, seat her in a carriage, and, if the police had no objection, unharness the horses and on their own shoulders carry her to the Coulon Hotel (now the European), where newly decorated and expensive apartments awaited her… Schneider is coming! Ah! Allons, il y a encore des beaux jours pour la cascade!” [11]

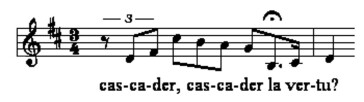

Cascade had become a byword for untrammeled debauchery. It derives from Helen’s aria in La Belle Hélène, when she bemoans her fate, the gods having decided to make this faithful wife commit adultery.

The “cascader” moment from the “Invocation of Venus” in Offenbach’s “Belle Hélène”.

Dis-moi, Vénus, quel plaisir trouves-tu / À faire ainsi cascader ma vertu? (Venus, pray tell, why does it divert you / To find such devices to topple my virtue?)

Cascade is French for waterfall, but in nineteenth-century theatre it took on a new meaning, to describe slapstick in the pantomimes of Deburau, “a romantic form, a great schism with the classic school.” Cascades were “kicks, slaps, and cudgellings,” [12] the physical comedy of a clown routine. The safeguarded virtue of Offenbach’s Helen of Troy is not ravished or violated or even surrendered; it takes a tumble, suffers a pratfall. This marvelously captures Hélène’s insouciant eroticism tinged with impudence. For Russians, however, it summed up all the audacious “naughtiness” they sought in French operetta. Journalistic prose was abundantly sprinkled with it and such coinages as kaskadalki (cute little cascaders). The aristocracy considered Paris to be the nec plus ultra in sexual license and Schneider was taken to be the epitome of Paris.

The opening night audience was composed of the cream of (male) Petersburg society and the female demi-monde.

The hall of the “Bouffe” theatre presented an unusual spectacle: all our “cocottocracy” showed up au grand complet. Bared shoulders, low-cut waistcoats, colossal yellow chignons, English partings, curled wigs, smoothly shining bald spots, ringlets, moustaches, side-whiskers,white-lead cosmetics, rouge, powder and cold cream – it all blended into one lively picture… A feverish expectation was expressed on every face,a sort of whisper and buzz ran from one end of the hall to the other… But now the triumphant moment was drawing near: on stage an aide announced the arrival of the Grand Duchess… Everyone fell silent, and all that could be heard was the impatient beating of hearts beneath the dazzling white shirts from Lecrètre and the impeccably tailored frock coats and uniforms from Brunst. [13]

This was the same audience that never missed a premiere at the Mariinsky ballet and the Italian opera. They expected Devéria’s daring performance of Helen at the Mikhailovsky to be child’s play compared to Schneider as the Grand Duchess.

Hortense Schneider as the Grande Duchesse de Gérolstein. (Photo: Ulric Grob, Paris. Collection Laurence Senelick)

She surprised them by not going beyond the bounds of art, by her humor and comic talent, mastery of dialogue and movement, as she executed the rondos Offenbach had written specially for her. She defied their expectations by her technique and her triumph was complete. Schneider played an enormous role not only in acquainting Russian audiences with a master class in performing operetta, but in enabling Russian actors to adapt it to the nascent Russian operetta. She earned her fifteen curtain calls and the bejewelled scepter for far more than “cascader la vertu.”

The reviewers tripped over themselves in praising Schneider. “On the boards of the Theatre Bouffe trod the resplendent star of the cascade world Hortense Schneider, enchanting old and young, purists and epicures by her exceptional talent, her chic and her legendary jewels cultivated with the blessing of Allah by the almighty Khedive Ismail Pasha on the poor and arid soil of Egypt for the decoration of the superb brow and antique bust of the bewitching houri Hortense,” wrote Siyanie [Radiance].

Ismail Pascha, Khedive of Egypt. (Photo: United States Library of Congress)

(The Khedive has visited her in Paris and hoped she would sing at the opening of the Suez Canal, but he had to be contented with Céline Montaland.) “An enchantress, definitely a sorceress!” gushed I. R., of Birzhenye vedomosti [The Stock-exchange News], “the piquant lioness of the season.” [14] Her ostensible intimacy with the Tsar (she was rumored to have dined with him and perhaps more [15]) allowed fuller versions of the operettas to be performed.

Tsar Alexander II. (Photo: National Archives of Canada)

Debating Depravity

When Schneider departed on December 14, after adding Boulotte and Hélène to her two months of triumph, she was probably unaware of the intellectual turmoil she had stirred up. Even before the founding of the Bouffe, the Russian cultural establishment, confronted with the phenomenal popularity of French comic opera and its licentious atmosphere, sought a prophylactic against this foreign contagion. Numerous were the editorials, caricatures, open letters, occasionally accompanied by a serious analytic article. For Russians art had to serve a higher purpose, possess social relevance and serve progressive ends.

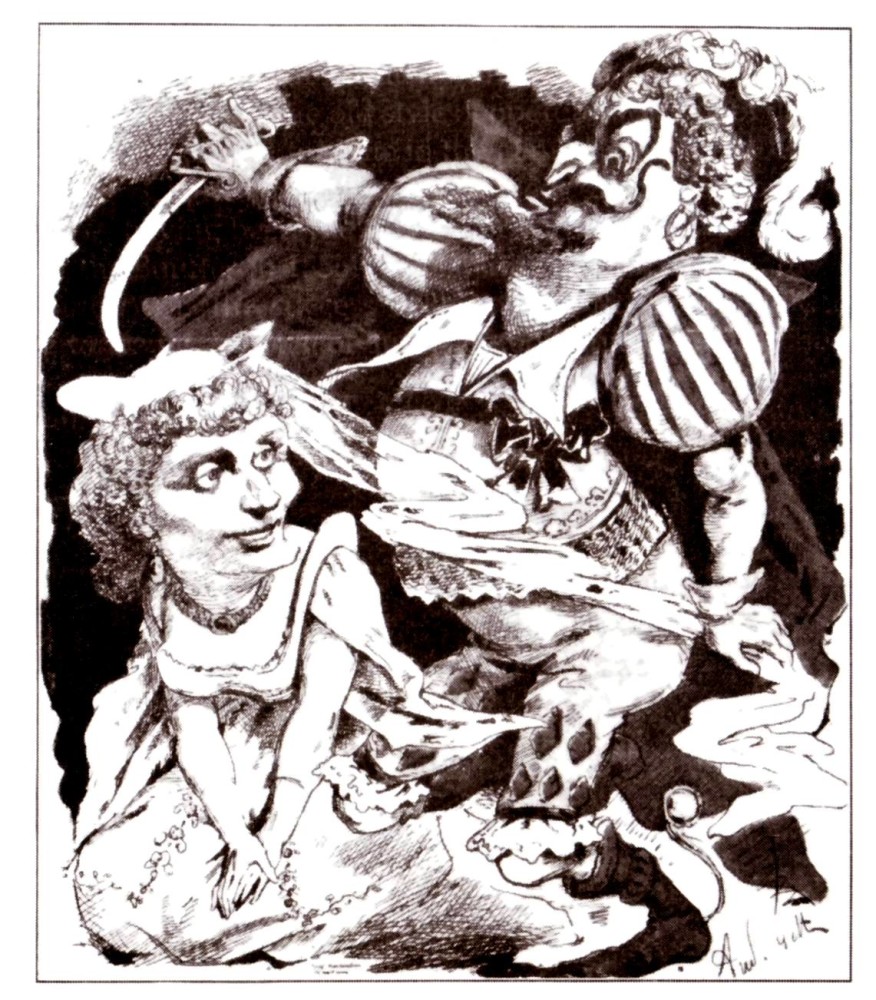

The original stars of “Barbe-bleue”: Hortense Schneider as Boulotte and the tenor Dupuis in the title role, caricature by Gill in “L’Eclipse.”

In the Slavophile camp, the bureaucrat Mitrofan Shchepkin found the whole genre “untalented, insignificant and cynical,” and the playwright Aleksandr Ostrovsky denounced it as alien immorality, distracting the populace from the need for a native repertory. [16] The musical world, including the prominent César Cui and Aleksandr Borodin, regarded Offenbach’s works as trivial and nonsensical, purely European phenomena irrelevant, even harmful, to the progress of Russian opera.

The opposing faction also had misgivings. The most bizarre expression of this was the radical Nikolai Mikhailovsky’s article of 1871, “Darwinism and Offenbach’s Operettas,” which appeared in the thinking man’s journal Notes of the Fatherland. Mikhailovsky declared them both a legacy of the Enlightenment and the destructive principle of the French Revolution. . Darwin advances science and Offenbach advances Voltairean satire, both in opposition to established order. Mikhailovsky regarded the operas as specific exempla of philistine liberalism converging and gathering momentum to legitimize the worst aspects of bourgeois culture. He considered the development of operetta to be “an historical atavism,” promoting immoral principles. Perhaps the French had lost to the Prussians in 1870 because their morale had been sapped by operetta. Offenbach’s operas are “not only an agent but a symptom” of change. [17]

Nikolay Konstantinovich Mikhailovsky, Russian journalist, sociologist and critic. (Photo: WikiCommons)

The censorship office of the Ministry of Internal Affairs was alarmed by Mikhailovsky’s implication that Darwin and Offenbach were harbingers of revolution, urging that antiquated concepts should be overthrown and replaced by a new order. Nevertheless, the censors were content to reprimand Notes of the Fatherland and never considered banning the source of contagion, opéra bouffe itself. [18] It was enjoyed by too many officials at the highest levels of government.

!["Orphée aux enfers" at the Bouffe. Drawing by Broling. Vsemirnaya illyustratiya [Universal Illustrated] 97 (1870), in V. Vsevolodsky-Gerngross, Istoriya russkogo teatra (1929).](http://operetta-research-center.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Screenshot-341.jpg)

“Orphée aux enfers” at the Bouffe. Drawing by Broling. Vsemirnaya illyustratiya [Universal Illustrated] 97 (1870), in V. Vsevolodsky-Gerngross, Istoriya russkogo teatra (1929).

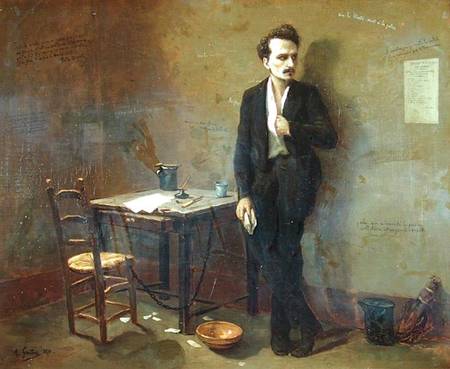

Henri Rochefort in prison, 1871. (Painting by Armand Gautier)

He noted that although The Grand Duchess had been banned during Lent (when all theatres were closed), the Alexandrovsky’s Lyadova was singing excerpts from it and Helen’s Invocation to Venus in concerts. [19] Because they were not “legitimate” houses, Berg’s Theatre and the Bouffe were allowed to perform during Lent, adding to their popularity and financial success. The witty versifier A. Chistyakov wrote: “In Lent of shows we are bereft/Tragedy, drama, opera all gone poof!/ The only amusements we have left/Are Berg and the Théâtre Bouffe.” [20]

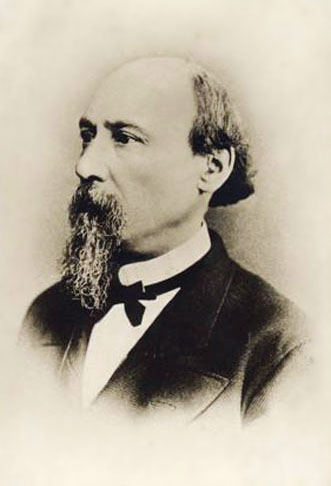

Portrait of the publisher and publicist Alexey Suvorin. (Paiting by Ivan Kramskoy)

When Hortense Schneider created a furore, Suvorin thought the press praised her to show they were capable of appreciating European art. He feared that she pandered to the audience’s worst impulses.

As one watches her, one might call to mind certain verses of Heine, which seem to blend passion and tenderness and grace and humor and malicious sarcasm about the holiest things and the most vulgar human feelings, without distinction but in a kind of harmonious order, which expresses the artist’s feelings. Were Mlle Schneider not to cede to the coarse instincts of the crowd, which demands bold strokes, she might present that aspect of her role even better and more rigorously… She sings the aria “Dites lui” with Bacchic movements of a completely unbridled female nature… I know I’ll be pilloried as a moralist, but I am convinced that stage art should have limits, that there are certain pathological and physiological phenomena in life which, taken separately, cannot appear on stage, out of respect for art and for man as a moral individual. [21]

However, he concluded, only somewhat ironically, “Hurry, gentlemen, and see Mme Schneider. It’s worth it!”

After Schneider was blamed for “the immorality of our society”, Suvorin reconsidered and took up the cudgels in her defense. In his ultra-conservative magazine Grazhdanin [The Citizen], the retrograde and xenophobic Prince Vladimir Meshchersky cited as his worst-case-scenario The Grand Duchess at the Bouffe, which mocks “patriotism with an immorality unlike anything in the annals of the world.” For him, the adulation of Schneider represented “a danger threatening the government and society” worse than anything in Russian history, worse even than the nihilist terrorist Nechaev’s murder of a comrade. He denounced The Grand Duchess as “profanation,” “a sign of the times,” “a picture of all-round licentiousness.” [22]

To counter this hysterical hyperbole, Suvorin replied that Schneider did not engineer the fall of the Second Empire but was the “least consequence of a host of causes,” merely a talented exponent of French esprit. “Once upon a time the French flew the banner of civilization from bayonets, now they fly it from their legs.” Popularity of Offenbach among the Germans had not vitiated their victory over the French. As to the mockery inherent in a female-run kingdom, it had its objective correlative in the court of ex-Queen Isabella of Spain, a notoriously loose-living monarch. [23]

As Murray Frame points out, these journalistic skirmishes were symptoms of a deeper conflict within Russian society and ideology. In the wake of the Great Reforms of the 1860s, politics became polarized, with the conservatives and reactionaries eager to prevent further erosion of the autocracy, and the liberals and radicals avid to advance greater democracy. In this polemic, operetta could be maligned as a corrupting influence or praised as a progressive one. Offenbach’s mockery of authority and the growth of an urban theatrical audience with appetites rather than taste were straws in the wind, indicating whatever the polemicist chose to emphasize.

Carrying-on at the Bouffe

Schneider’s international prestige and rumored intimacy with the tsar had protected the Bouffe during her tenure there. Once she departed, the authorities found ways to harass it. In 1873 a correspondent to the Sovremenny listok [Contemporary Leaflet] reported that two of its singers had been brought before a magistrate: the charges were that Blanche Gandon, in Les Cascades de Théâtre Bouffe had been “improperly clothed, or rather unclothed,” and Louise Philippeau had been “making improper gestures in the cancan of ‘L’Amour ce n’est que cela,’ said gestures not being included in her part.” These were specified in the journal Delo [Business] as “shameless bodily movements.” [24]

Philippeau had had her start at Egarov’s Demidov Garden. Gandon, regarded by Russians as the “most Parisian of Parisiennes,” actually hailed, according to the music-hall singer Paulus, from Lyons. [25] In Montpellier in 1867 when she had appeared as Marguerite in Faust, she was described as “an appealing young woman with refined manners”; even then “her eccentric toilette, her by-no-means unattractive chignon attract attention…this young singer awaits a bright future.” Her demure qualities were not durable: at Berg’s she had sung about “la chose” (“the thingy”). [26]

Blanche Gandon. (Photo: unidentified. Collection Laurence Senelick)

The actresses and the manager of the Bouffe were summonsed along with witnesses: Messrs Zeidlits, Annenkov and Tasikov, officers who “seldom went to the theatre” and found the appearance and demeanor of the two actresses “demoralizing,” and Staff-Captain von Kremer and a Mr Lopatin who “often went to the theatre” and said “they didn’t mind.” The magistrate observed wryly that, since those who rarely attended the theatre were shocked by the actresses’ behavior, while those who frequently attended “didn’t mind,” the effect must be demoralizing. Louise Philippeau pleaded “first offense” and the encouragement offered her by the audience; Blanche Gandon turned out, however, to have been convicted before for a similar “wardrobe malfunction.”

According to newspaper reports, while performing a song, Gandon lifted her leg so high that she lost her balance and fell flat on the floor; while prone, she continued to make various physical movements, displaying her knickers. The policeman on duty drew up a report accusing her of immodest behavior. Her father claimed that she was so young she could not be held responsible; as a minor, she had no civil rights and he had to sign all her contracts (despite her singing a lead in Faust six years before!). Her newly-fledged lawyer, who bore the illustrious name Turgenev, tried to prove there was no intentional immodesty; his client had simply lost her balance and floundered on the stage, trying to get up as quickly as possible. To dazzle the all-male jury, he pulled out a bundle containing her panties which he wished to enter as material evidence (a forecast of the 1958 film Anatomy of a Murder!). The judge had been unimpressed and fined Gandon 150 rubles. [27]

The magistrate in the later trial was equally unyielding. When Philippeau pleaded that the audience had egged her on, he ruled. “If the audience encouraged you, that is an additional reason why I should punish you both, so as to impress upon you that what some may deem worthy of applause is highly reprehensible.” Gandon was sentenced to a fine of 100 rubles or a month’s imprisonment, and Philippeau 50 rubles or a fortnight in jail. The fines were to be applied to “the fund for the maintenance of prisons.” [28] Neither actress was daunted. Philippeau, allegedly kept by a local dignitary, made enough of a fortune to run her own establishment in later years. Gandon remained at the Bouffe, playing the responsible role of Oreste in Belle Héléne in its 1876/77 season.

A New Regime

Such nuisances may have made Egarev disillusioned with managing the Bouffe, and he left it to concentrate on his many other projects. The theatre came into the hands of an actor and playwright A. F. Fedotov; his French was far from fluent, a drawback in running a Francophone company. However, by doubling the size of the fee paid to the administration of the Imperial Theatres, he received permission to stage full-length spectacles under their original names. He rechristened the theatre the Opéra Bouffe, and, hoping to emulate the drawing power of Hortense Schneider, imported other headliners from the Parisian stage.

Publicity photograph of Léa Silly as Oreste in the first production of “La belle Hélène”. (Photo: WikiCommons)

They included Léa Silly (1872-73); Zulma Bouffar (1875-76) as Fantasca in La Reine Indigo; Paola Marié (1876-77), Louise Théo who won plaudits in Pomme d’Api and Mme l’Archiduc (1877) [29]; and Jeanne Granier who repeated her success as the first Giroflé-Girofla. The only import who came close to duplicating Schneider’s impact, however, was Anna Judic. She arrived in St Petersburg in March 1874 and before her departure in May had played Madame l’Archiduc (renamed for diplomatic reasons Madame Ernest), La Timbale d’argent, La Branche cassée, Bagatelle, and Giroflé-Girofla. [30] In place of Schneider’s voluptuous ribaldry, Judic offered a faux-naïf approach to innuendo. Her theatricalized version of music-hall singing captivated spectators by a distinctive comic talent, graceful gestures and expressive mimicry. According to one critic, she “could with rare skill plant the innocent violet of a lyric within the most garish bouquet of indecency… Judic created her own genre, the essence of capricious grace and whimsical eccentricity.” [31]

Judic in “Le Timbale d’argent”. The exposure of armpits was considered a provocative gesture. (Photo: Gaston & Mathieu, Paris. Collection Laurence Senelick)

The composer Modest Musorgsky was a great fan, coming twice to savor Judic in Madame Ernest in 1875. He wrote enthusiastically to his friend, the composer Count Golenshchikov-Kutuzov: “Within his little world [Offenbach] is an appealing and well-bred artist.” The music and the performance contained “no superfluous gestures… no mindless forcing of the voice… no indecent twitching or grimaces.” And no cancan. [32] Judic also enthralled Stanislavsky. Even Nikolay Nekrasov, the populist poet of “Who Can Live Happy in Russia?”, devoted a verse to her:

Madonna’s cheek,

A cherub’s gaze…

Madam Judic

Does us amaze.

Our life goes poof,

An empty shell,

Only the Bouffe

Can amuse us well.

The excited shriek,

The blissful interjection…

Madam Judic

Is truly past perfection. [33]

Nikolay Nekrasov. (Photo: Vezenberg & Co.)

She returned twice to the Bouffe to help swell the box-office, appearing in Lecocq’s Les Cent Vierges (innocuously retitled The Green Island), and in 1876 a farewell benefit was held for her with the participation of the whole troupe. Judic was supposed to return the following year, but the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War kept her at home.

By 1874 the Bouffe had become, in the words of one contemporary (Pyotr Stolpyansky), “the center of merry-making in Petersburg.” Nekrasov’s doggerel is but one example of how the Bouffe was so imbedded in the popular imagination that it frequently turned up in fiction as shorthand for dissipation. Ostrovsky in his play Wolves and Sheep, has Glafira, the penniless young ward of a tyrannical old lady, remember that once she lived “a gay life” in Petersburg and excitedly recalls her visits to the Bouffe. It seems to be an obsession of the satirist Saltykov-Shchedrin: he mentions it in his novel The Hon. Golovyovs, refers to Schneider in his ”Letters to Auntie” and in The History of a Town has Blanche Gandon perform in the local riding-school.

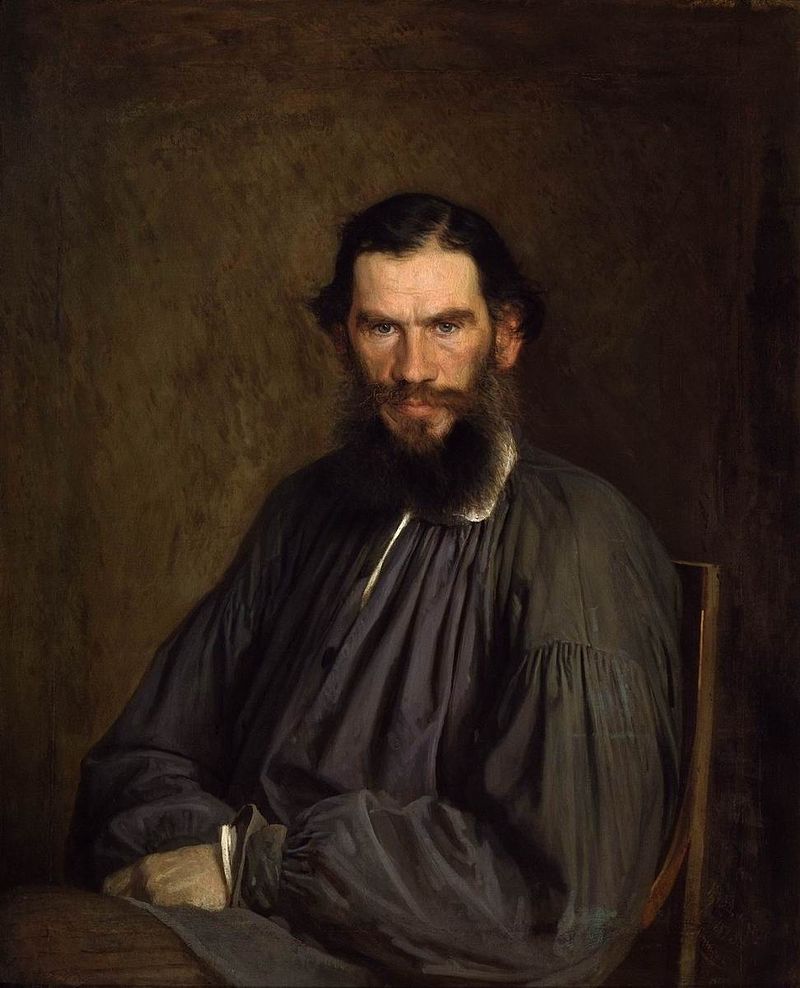

Portrait of Leo Tolstoy by Ivan Kramskoi, 1873.

Not even Tolstoy was immune. In Anna Karenina (1875-77), he uses the fashion for racy entertainment to cast a sidelight on Count Vronsky who confesses to regular attendance: “I do believe I’ve been there a hundred times, and always with fresh enjoyment. It’s exquisite! I know it’s disgraceful, but I fall asleep at the opera, yet at the Bouffe I sit up to the very end and have a good time.” When Vronsky attempts to describe the leading actress to an ambassador’s wife, she insists he is not to speak of such a “horror.” “’Well, I won’t, especially since everyone knows those horrors.’ ‘And everyone would go there, if it were as accepted as the opera,’ chimed in Princess Myagkaya” (Part 2, vii).

Aaron Taylor-Johnson as Count Alexei Kirillovich Vronsky in the film version of “Anna Karenina” by Joe Wright. (Photo: Universal Pictures International)

After Judic’s final appearance, the Opéra Bouffe continued to attract audiences for one more season, but without a star attraction enthusiasm waned. In April 1878 it closed. Attempts to revive the empty building with pantomime and circus acts were unsuccessful and it was soon demolished, its territory absorbed into the Anichkov court park.

The Bouffe’s decline may be attributed to a number of factors. The high cost of importing Parisian stars and the fees paid the Government could not be offset by the box-office. The auditorium’s dimensions prevented an expansion of the audience. Gradually, Russian versions of French comic opera began appearing on the stage of the state-subsidized Aleksandrinsky, making it more accessible to the middle-class spectators who cultivated native stars, such as Vera Lyadova. One Moscow journal opined, “For a whole theatre to be devoted exclusively to the operetta repertoire…the possibility of giving 184 performances (a season), to pay vast sums to Judic and Théo and other operetta prima donnas – all this, to our Muscovite way of thinking, is incredible and points up the enormous difference between Petersburg and Moscow relative to the make-up of the theatrical public. Let’s recall that in Moscow a miniscule French troupe could barely survive and performed in the little Solodovnikov Theatre to an empty house.” [34] In addition, the growing profusion of cafés chantants allowed patrons to eat, drink and smoke while they listened to a succession of songs far more scabrous and watched actresses far more undressed than even the Bouffe dared present.

The political climate also contributed to the Bouffe’s decline. Throughout the lifetime of the theatre, the populist or Narodniki movement, dedicated to educating the peasantry, had been severely repressed by the police; the result was to funnel many of its members into the more extreme People’s Will party which preached terrorism and assassination. A mood of anxiety pervaded Petersburg. This was abetted by anti-Ottoman sentiment, stirred up by uprisings in Bulgaria and Serbia. It culminated in the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-78. Most of the young officers who had made up a conspicuous contingent of the Bouffe audience were now in the field.

The name lingered. In 1901 a summer theatre opened as Theatre Bouffe (Teatr Buff), but it was family-oriented and high-toned in its offerings, which included the Russian premiere of The Merry Widow.

The Bouffe Summer Theatre, around 1909. (Photo: Postcard from the Collection Laurence Senelick)

It lingered until the 1920s when new Soviet imperatives condemned it as “frivolous.” The present Teatr Buff, opened in 1983 in a former cinema and located on the opposite bank of the Neva at a great distance from the site of its namesake, offers plays, musicals and children’s theatre, an eclectic bill primarily attractive to tourists. In Putin’s Russia, anything smacking of sexual impropriety, especially of foreign extraction, has been ruthlessly abolished.

Laurence Senelick. (Photo: Private)

Laurence Senelick is author of A Historical Dictionary of Russian Theatre (2015); Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture (2018); and The Final Curtain: The Art of Dying on Stage (2022).

[1] Nikolaĭ Gerasimovich Savin, Sudʹba avantyurista: zapiski grafa Nikolaya Gerasimovicha de Tuluz-Lotrek-Savina, otstavnogo korneta, veterana boev pod Plevnoy, pretendenta na prestol Bolgarskogo Knya︡zhestva, rossiyskogo, velikobritanskogo i amerikanskogo poddannogo, ofitsera armii SShA, uchastnika ispano-amerikanskoĭ voĭny 1898 goda na Kube … (1913), ed. S. V. Shumikhin (Novosibirsk: Svinʹin i synovʹya, 2012), Ch. 5. Bazarov is the radical anti-hero of Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons; Ernest Renan the author of a rationalist life of Jesus; nihilist was as common a term of abuse for left-wing dissenter in Tsarist Russia as communist was in 1950s USA.

[2] Yury Alyansky, Uveselitel’nye zavedenija starogo Peterburga (St Petersburg: Avrora; Stroyizdat SPb, 2003), 46.

[3] Irra Petrovskaya and Vera Somina, Teatral’ny Peterburg nachalo XVIII veka-oktyabr 1914 goda: obozrenie i putevoditel’ (St Petersburg: RIII, 1994), 161.

[4] Roux starred at the Bouffe until 1873 when he returned to Paris and the Théâtre des Variétés to replace the deceased Kopp in Lecocq’s Les Cent Vierges. The rest of his career was undistinguished.

[5] E. D. Uvarova, Kak razvlekalis’ v rossiyskikh stolitsakh (St Petersburg: Aleteyya, 2004), 91-92.

[6] Henri Vignaud, “Revue musicale,” Le Mémorial diplomatique (17 avril 1867).

[7] Visitors are said to have included Napoleon III, the Prince of Wales, the King of Portugal, Alexander II of Russia and the Grand Duke Constantine, Adolphe Thiers, Chancellor Bismarck, Emperor Franz Joseph, the Count of Flanders and the Khedive of Egypt Ismail Pasha. The most up-to-date account of Schneider’s career can be found in Dominique Ghesquière, La troupe de Jacques Offenbach (Paris: Symétrie, 2018), 285-308. Jean-Paul Bonami’s La diva d’Offenbach. Hortense Schneider 1833-1920 (Paris: Romillat, 2002) is anecdotal and unannotated.

[8] Gustave Lafarge, “Courrier des théâtres,” Le Figaro 226 (oct. 1871): 4.

[9] L. P., “Courrier des théâtres,” Le Figaro 237 (5 nov. 1871), 4.

[10] A. F. B., Chastnye teatry i frantsuzkie artisty v S.-Peterburge (St Petersburg, 1878); Teatr i iskusstvo 34 (1915).

[11] Pyotr N. Stolpyansky, Petrograd kak voznik, osnovalsya i ros Sankt”-Peterburkh (Petrograd: Kolos, 1918).

[12] Champfleury, “Trucs et cascades,” Souvenirs des Funambules (Paris: Michel Lévy, 1859), 5-6.

[13] Pyotr N. Stolyansky, “Kaskadnyy zhanr,” Stolitsa i usad’ba 49 (Petrograd, 1916): 20.

[14] Quoted in Ayansky, Uveselitel’nye zavedenija, 61-62.

[15] P. D. Boborykin, Vospominaniya v dvukh tomakh (Moscow: Izd-vo khudozhestvennoy literatury, 1965), I, 444.

[16] Institut istorii iskusstv Ministerva kultury SSSR, Istoriya russkogo dramaticheskogo teatra v semi tomakh, 1862-1881. 8 vols. (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1980) V, 62. Ostrovsky’s animadversions on operettas were summed up in his proposal for a national theatre, “Zapiska o polozheny dramaticheskogo iskusstva v Rossii v nastoyashchee vremya (1881),” Polnoe sobranie sochineny (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1973-80) X, 126-42.

[17] Nikolay Mikhaylovsky, “Darvinizm i operetki Offenbakha,” in Polnoe sobranie sochineny. 3 vols. (St Petersburg: A. F. Marks, 1911), I, 229-56. Also see Insitut, Istoriya, VI, 63; M. Yankovsky, Operetta (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1937), 248-50.

[18] N. V. Drizen, Dramaticheskaya tsenzura dvukh épokh, 1825-1881 (Petrograd: Prometey, 1917), 249. Also see Murray Frame, “The early reception of operetta in Russia, 1860s-70s,” European History Quarterly, 42, 1 (2012): 29-49.

[19] A. S. Suvorin, “`Prekrasnaya Elena’ Offenbakha na russkoy stsene” (20 Oct 1868; 3 Mar. 1869), in Teatral’nye ocherki (St Petersburg: Novoe vremya, 1914), 234-37, 291-92.

[20] Quoted in Georgy Terikov, Kuplet na éstrade (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1987), 32.

[21] Suvorin, Teatral’nie ocherki, 12 Dec. 1871, 387-88, and 23 Jan. 1874, 387-91.

[22] V. P. Meshchersky, Moi vospominaniya. 2 vol. (St Petersburg: Tip. knyazhya Meshcherskogo, 1897-98), I, Part 2, 1865-1881, 170-71.

[23] Suvorin, Teatral’nye ocherki 13 Feb. 1872, 403-07.

[24] “Occasional notes,” The Musical World (London) (15 July 1873): 442; Delo, 626 (1871).

[25] Paulus [Paul Habans], Trente ans de café-concert, ed. Octave Pradels (Paris: Société d’Édition et de Publications, 1923).

[26] Savin, Sudʹba avantyurista: zapiski grafa Nikolaya Gerasimovicha de Tuluz-Lotrek-Savina…, Ch. 5.

[27] Pyotr N. Stolpyansky, Putevoditel’ po Kronshtadu (1872) (Petrograd: Gos. Izdatel’stvo., 1923).

[28] “Occasional notes”, 442.

[29] Ivan de Woestiyne, “Figaro à Saint-Pétersbourg,” Le Figaro 119 (avril 1877): 1.

[30] Gustave Lafargue, “Courrier des théâtres,” Le Figaro 324 (déc. 1874): 3; Jules Prével, “Courrier des théâtres,” Le Figaro 60 (mars 1875): 3.

[31] A. R. Kugel, “Zhudik,” Teatr i Iskusstvo 15 (1911): 318.

[32]18 Mar. 1875. Quoted in David Brown, Musorgsky his life and works (London: Oxford University Press, 2010), 296.

[33] “Yubilyary i triumfary,” quoted in Alyansky. Uveselitel’nye zavedenija, 48.

[34] Teatral’naya gazeta 56 (Moscow, 1877), quoted in Yankovsky, Operetta, 250.

So, so good to read outstanding original research … LOVED this.

PS The BARBE-BLEUE photo I have repertoried as from the drama rather than the opéra-bouffe. Am I wrong?