Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

23 December, 2024

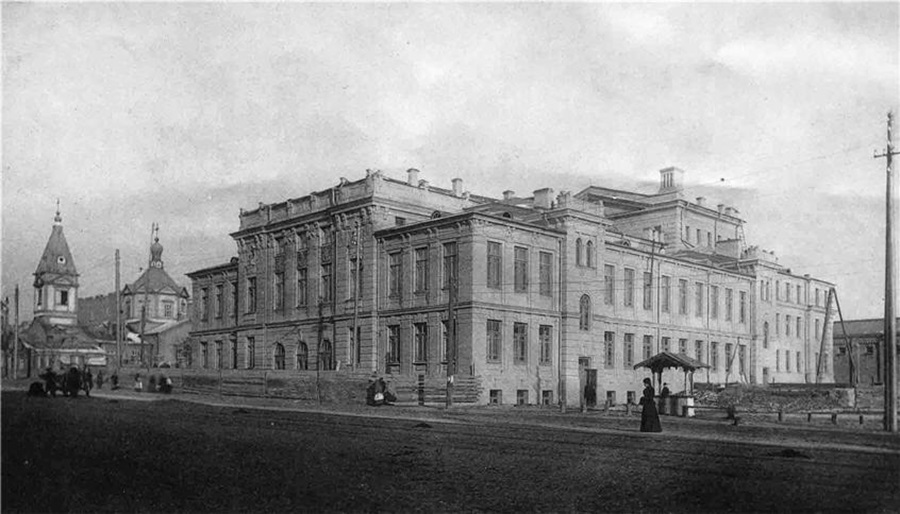

Yes, there is an institution called National Operetta of Ukraine. It has been situated in the National Academic Theater of Operetta (“NATO”) since 1934, after the building itself had already been erected in 1902 as a kind of public education/community venue where Ukrainian culture was to be promoted, a culture otherwise suppressed by the Russians. Now, in 2024, the company celebrates its 90s birthday at a time when Ukrainian culture is once more under heavy attack from the Russians.

The public house “Trinity” in Kyiv at the beginning of the 20th century, as seen on an old postcard.

When the Operetta Research Center received an invitation from culture manager Sebastian Schwarz to come to Kyiv to deliver a talk at a conference and attend a gala concert the next day to celebrate the 90 years of this operetta theater the author of this article, who was asked to come, thought it was a joke. First of all, who in their right mind would travel into a war zone the week before Christmas, or at any other time? And secondly, what kind of topic would they want to hear about from someone like me, a researcher with a very clear profile regarding themes I deal with? Would queer operetta perspectives be something Ukrainians might be interested in? (Mmmmm.)

Poster for the 90-Years-Gala concert at the Kyiv operetta theater. (Photo: National Operetta of the Ukraine)

After a lot of thinking and heated discussions with friends and family, I agreed to go. Because, obviously, seeing a place with my own eyes that’s on the news almost daily and talking with people who live/work there under the current circumstances would be a unique opportunity. As it turned out, it was also an existentialist experience: very frightening at times (when Russian missiles hit and you are shaken out of your sleep by the explosions), but also inspiring when you see how life goes on and people arrange themselves with the impossible situation of non-stop attacks, death and destruction.

Part of the ‘arrangement’ is that people in Kyiv long for an escape from reality. They flock to the theater to forget the horrors of everyday life for a few short hours. All performances in almost any theater are always sold out, it’s difficult to get tickets for anything. (Or so I was told). And this applies to NATO, too.

The auditorium of the operetta theater in Kyiv. (Photo: National Operetta of the Ukraine)

It’s a building that was only recently renovated, during the Corona lockdown of 2021, in a pompous Disney-esque style that’s a bit too much, some might say it’s lush, others will find it overstuffed. But the auditorium is cozy and impressive. A small exhibition in the upper foyer lets you see – divided into four sections – the performance history of various famous pieces, many by Emmerich Kalman, whose Zirkusprinzessin (with its Russian setting) holds a special place in the repertoire.

People standing in line for the big gala concert in Kyiv. (Photo: National Operetta of the Ukraine)

One of the more interesting things I learned while talking with the people at the operetta theater is that apart from the escapism the audience has special needs in times of war. Which applies especially to soldiers returning from combat. Many are traumatized and cannot bear hearing ‘loud’ music. Whenever the music goes beyond a certain level, they hold their hands against their ears or simply get up and leave the auditorium. Also, many have been blinded or have lost their hearing. So the theater is trying to account for that with special audio descriptions that they provide via headphones or other forms of making it possible for soldiers to follow the action on stage when they attend performances with their families and loved ones.

A soldier from the ensemble addressing the audience during the gala concert. (Photo: National Operetta of the Ukraine)

From the ensemble of the operetta theater two men who had been sent to the front lines have been killed. At the gala last Thursday there was a minute of silence for them. Also, an ensemble member who is currently at the front sent a video message. You saw him in full combat gear, talking into the camera, while in the background bombs exploded, reminding everyone that this is a deadly serious situation.

Vitaly Klitschko attending the gala concert in Kyiv. (Photo: National Operetta of the Ukraine)

In other sections of the entertainment industry, veterans who were injured are shown with their injuries. This is a conscious decision to not do things like in Soviet times when the wounded were kept out of sight, so as to not disturb the ‘heroic’ aura the government wanted to transport.

On the current Ukrainian version of The Bachelor, the protagonist of that reality tv show is an ex-soldier who has lost both his legs. He’s the guy shown on national television as the object of desire for the female contestants. At the operetta gala no such examples of inclusivity were visible, sadly.

The gala itself, which was advertised all over town and which was attended by mayor Vitaly Klitschko, was a surprisingly ‘old fashioned’ affair. Put together by older men in a way that many will remember from operetta companies in Budapest or Dresden in the 1980s or 90s. There were mash-ups and selections from Merry Widow, Csardasfürstin, Gräfin Mariza and Bajadere. Presented by pompous voices, with dancers in nondescript ‘traditional’ costumes prancing around to an equally nondescript choreography. In part 2 of the gala we got musicals ranging from The Phantom of the Opera to Mozart.

As much as I understand the need for escapism, that was a form of escapism that I thought the world had outgrown long ago.

The ensemble at the operetta gala in Kyiv. (Photo: National Operetta of the Ukraine)

There were no soldiers or many young people visible at the gala, it was mostly elderly ladies in fur coats that made me wonder for whom this celebratory concert was intended.

The day before the theater hosted a conference whose core question was: how to get subsidy to finance tours throughout Europe and the world. I seriously doubt that this particular type of operetta performance has many unique selling points. There was nothing remotely Ukrainian about it in terms of selected titles, and the Budapest competition (among others) offers such like spectacles with more polish and an almost identical repertoire. While others have shown that a more modern approach – in terms of casting, dancing, and choice of musical numbers – draws in bigger and more diverse crowds. If the NATO really wants to compete here, on an international level, they might want to change their game. Depend less on government subsidy, and aim more at global tastes in pop culture. Because young audiences in Kyiv are very Western and pop culture oriented, as I discovered in various conversations.

The male chorus line at the operetta gala in Kyiv. (Photo: National Operetta of the Ukraine)

NATO’s big advantage is that the historic Ukrainian operetta repertoire is completely unknown in the West. There are no recordings of the (few) major pieces, e.g. Mykhailo Verbytsky’s Pidhiriany (The Foothill Dwellers, 1864) and Mykola Lysenko’s Chornomortsi (The Black Sea Cossacks, 1872). Or, from the 20th century, Kyrylo Stetsenko’s Svatannia na Honcharivtsi (Matchmaking at Honcharivka, 1909) and Yaroslav Y. Lopatynsky’s Enei na mandrivtsi (Aeneas in His Wanderings, 1911) or Yaroslav Barnych’s Hutsulka Ksenia (Ksenia the Hutsul Girl). Not a single number from any of these pieces was presented at the gala (or discussed at the conference). Nor anything composed after the Stalinist crackdown. Nor later pieces written by people such as Oleksander Bilash, Hryhorii Finarovsky, Vadym Homoliaka, Anatol Kos-Anatolsky, V. Lukashov, Oleksii Riabov, Oskar Sandler, or Yakiv Tsehliar. There certainly is a lot to discover and worth listening to.

Composer Isaak Dunavevsky. (Photo: Wikipedia)

And that also applies to Isaak Dunayevsky, who was born in the Ukraine in 1900, left his Jewish heritage behind and became one of the most prominent Soviet operetta composers, with hits like The Wind of Liberty/Free Wind (1947).

At the conference, I was allowed to talk about operetta performances in Prisoner of War camps during WW1, where they had (by necessity) all-male casts, and I spoke about all-male operetta concerts in WW2 put on by Nazi soldiers.

Wehrmacht soldiers in WW2 performing at the front lines. (Photo from Martin Dammann’s “Soldier Studies: Cross-Dressing in der Wehrmacht”, Hatje & Cantz Publ.)

I compared these to modern day all-male and all-female productions by Sasha Regan in the UK and productions of 1776 or Jesus Christ Superstar (or Wiener Blut) with only women. Arguing that such like productions brought popular musical theater back to the original cross-dressing ideals of Offenbach. This caused a rather heated discussion, with a lot of questions and noticeable support from the younger section of the (student) audience at the conference. Many of whom where not present at the gala the next day, by the way.

Tom Senior as young Frederick with the daughters of General Stanley, as seen back at Wilton’s Music Hall in a previous staging by Sasha Regan. (Photo: Scott Rylander)

Obviously, there would be a lot more to say about my days in Kyiv. And about the operetta theater. But suffice it to mention that the people I and Stefan Frey as my fellow research colleague from Germany spoke with were incredibly supportive, helpful and friendly in every imaginable way. They made sure that despite the bombs and nightly alarms, despite the constant Russian terror and despite an operetta ideal that is not mine we felt comfortable at all times. And even when our trip home underwent some radical last-minute changes, our fabulous hostess Elena Tsyba

was there – around the clock – to make sure we were taken care of.

So, I can only state with sincere gratitude that I wouldn’t have wanted to miss any of this. If the gala itself was the low point of my trip, the trip itself was a memorable one. And the reactions from some of the young people at the conference to my operetta talk made it all worthwhile for me because I had the feeling of having ‘reached’ someone. (You can always tell from the way they look at you.)

Stefan Frey and his wife Susan (left) with Kevin Clarke from the Operetta Research Center and our hostess Elena Tsyba. (Photo: National Operetta of the Ukraine)

Elena and the team from the theater showed us the city, gave us food and a lot of vodka. They showed hospitality in a time when that could not have been their first priority. And they expressed immense gratitude that we had come under such challenenging circumstances (when noone else from the operetta world would travel there, being present via Zoom, if at all.) For all of that I want to say: thank you from the bottom of my heart.

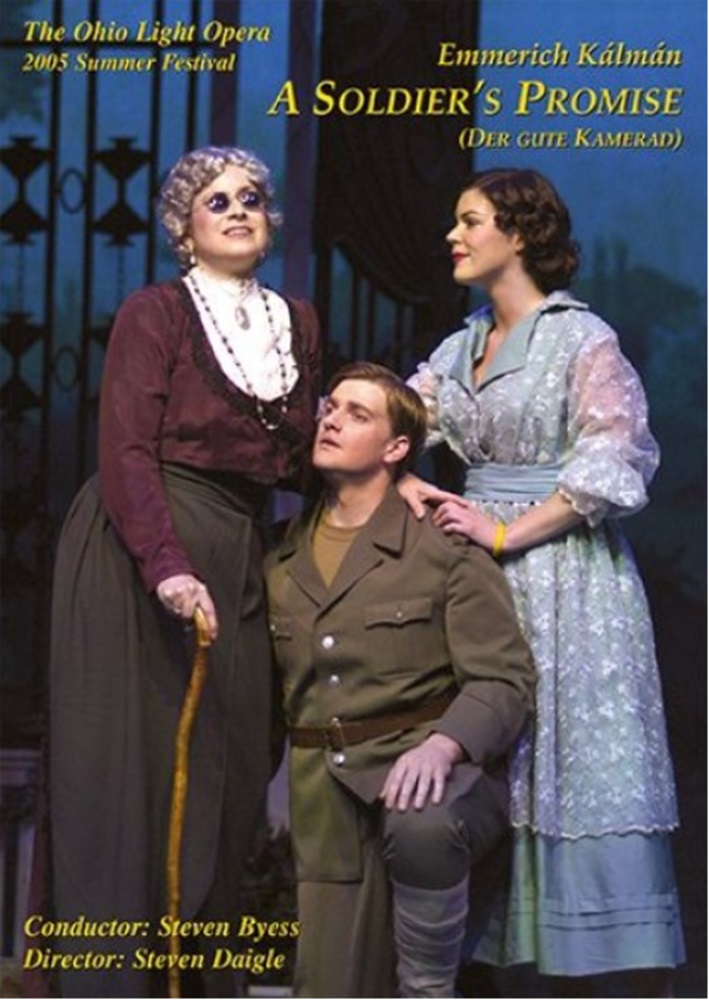

It was a week that changed my views of many things. Including operetta. Because it made me understand (better) how Kalman pieces such as Her Soldier Boy must have worked for their original war-time audience. (Sadly, that piece was not part of the Kalman gala mash-up.) It also made me realize that operetta is particularly adept as a ‘pain killer’ when performed in a certain way. And that one can indeed come to the genre as a veteran of existentialism, as Bertram K. Steiner once put it.

Kalman’s “Der gute Kamerad” as “A Soldier’s Promise”, 2005 production by Ohio Light Opera released on DVD. (Photo: Operetta Archives)

The morning after the gala three Russian missiles hit Kyiv, one blew up an office building a mere 800 meters away from the operetta theaters, destroying seven embassies nearby and a church. The theater itself remained unharmed, but it currently needs a generator to supply it with electricity during power backouts. Under suchlike circumstances, who am I to criticize the programming or stylistic approach to operetta at NATO? I can only wish everyone there the best for the future. And hope they stay alive, giving them a chance to one day bring Ukrainian titles to the West, to show the world (and themselves) what these ‘local’ operettas sound like. Pieces that are not part of the most recent publications on operetta under Socialism (read more about that here) or books on operetta in different national regions (read more here).

Stefan Frey and Elena Tsyba (left) with Sebastian Schwarz and Kevin Clarke at the operetta conference in Kyiv. (Photo: National Operetta of the Ukraine)

The Bachelor might have found a more up-to-date way of dealing with the situation. Maybe one day this concept will successfully be applied to operetta in Kyiv too. (One of the female assistants of NATO raved about this tv show, so it must reach someone… her, for example.) A 24-year-old Ukrainian student I spoke with at the gala – he was the plus 1 of Sebastian Schwarz who suggested my name for the conference (also for that: a big thank you!) – told me that the music and type of performance was not something he needed to see/hear again. I wholeheartedly agree.

A lady with red hair and a fur coat at the operetta gala in Kyiv. (Photo: Private)

But it shall be interesting to see whether the veterans or other people will ‘need’ to see operetta like this. And I sincerely hope that operetta in times of war will be analyzed more closely by researchers, because it’s a mostly overlooked topic, but an important one, nonetheless. Not just for the inhabitants of the Ukraine.

PS: Elena, if you read this … a merry Christmas to you, even under circumstances like these!

To hear/read Stefan Frey’s account of the Kyiv visit on the Bavarian radio, click here.