Kurt Gänzl

Operetta Research Center

2 February, 2012

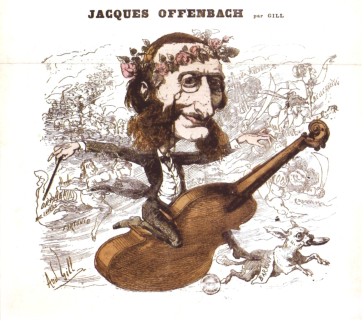

What became eventually known as “operetta” or “opérette” didn’t start its life under that name. The earliest works of the groundbreaking Hervé, and of Jacques Offenbach and his varied collaborators were designated under a whole series of finely frivolous titles. But, each and every one of those descriptions – culminating in the memorable term ‘opéra-bouffe’ during the 1850s and 1860s — spelled out to the theatregoers of the day exactly what they were going to get. Crazy fun and laughing music and – once its authors’ initial little ventures blossomed into full-length shows – girls, girls, oh wow, little could-they-be-bare-legged girls, winking and nodding at you – surely it was at you – from the stage. Opéra-bouffe – taken between dinner and a dalliance – was indeed the thinking man’s naughty night out on the town.

Jacques Offenbach riding his success, a caricature from a Paris newspaper.

French opéra-bouffe rose to its heights in the 1850s and 1860s, and came crashing to its end with the Franco-Prussian war, and the changes of mentality and social life that that war brought in Paris. But while it lived, it glittered as perhaps no other era of musical theatre has ever done since: Orphée aux enfers (1858), La Grande-Duchesse (1867), Barbe-bleue (1866), Hervé’s historico-loony Chilpéric (1868 ) and Le Petit Faust (1869), Offenbach’smedieval romp Genevieve de Brabant (1859), La Belle Hélène (1864), Le Pont des Soupirs (1861), Les Brigands 1869), Jonas’s Le Canard a trois becs (1869). The Théâtre des Variétés became the flagship of the Parisian musical theatre and a feature of the social life of French Empire, through half a decade and more, and the names of Lise Tautin (1834-1874), Zulma Bouffar (1841-1909), and, above all Hortense Schneider (1833-1920), the brightest star of the Offenbach shows at the Variétés, flamed at the forefront of the theatrical world, the social world and also of the demi-monde. The well-publicised off-stage activities of Mlle Schneider (she was not for nothing known popularly as ‘le passage des Princes’) only added, in fact, to her on-stage popularity, and while the princes in the audience angled for a ‘dinner invitation’, the public in the gods gaped in awe at the star who was on every man’s lips and every newspaper’s gossip and social pages.

It might have been thought that the works of the great writers of opéra-bouffe were so integrally a part of the life of the French Empire and its glittering and gadding society, that they would not export. But they did. They exported first to Vienna and the rest of central Europe and then even to the shores of England and across the oceans. They were translated – those works which it seemed could barely be adequately translated – into German, into Hungarian, into English and finally into a multitude of tongues. And – perhaps even more surprisingly – Austria, Germany, England, Budapest and New York found their own Hortense Schneiders and Zulma Bouffars. Marie Geistinger (1836-1903), and Josefine Gallmeyer (1838-1884), in Europe and Emily Soldene (1838-1912), in England and the colonies would become as celebrated in opera-bouffe in their own languages and their own parts of the world as the French star in hers. If these ladies were a little more circumspect about their private lives than Mlle Schneider, they nevertheless were not averse drastically to upping a hem or dropping a neckline, and they too reigned socially as well as theatrically in their respective spheres, even when the Empire had been and gone. And their audiences, too, were the same. At the Philharmonic Theatre, London, when Soldene played Genevieve de Brabant, the literati and aristocracy of the capital crowded the boxes and stalls, not to mention the back-stage and dressing-rooms, nightly, while the avid general (mostly male) public burst the galleries and the pit. And the lady recorded the scene for posterity in her notorious kiss-and-maybe-tell memoirs of 1896.[1]

Emily Soldene as Offenbach’s Helena.

England was wary and tardy in picking up and making a hit of opéra-bouffe, and the first efforts at playing such pieces as Barbe-bleue, Orphée aux enfers and La Belle Helene in London were unfortunate affairs: the sophisticated French material grossly re-arranged to resemble old-fashioned puns-and-rhymes English burlesque. And, as such, they failed. Only from the late 1860s did La Grande-Duchesse, Chilpéric and finally and enormously Genevieve de Brabant – more faithfully adapted, and maintaining the spirit of the original texts – take the town.

Vienna, however, was not shy, and by no means slow. Thanks to the enterprise of the manager-actor-author Karl Treumann, the one-act works of Offenbach in particular were given a showing at the little Kai-Theater on the banks of the Danube, as early as 1858. And where Treumann led, and found success, others followed. In the 1860s, the music of Offenbach reigned at Friedrich Strampfer’s Theater an der Wien and at the Carltheater.

But Treumann and Vienna ventured in another way, too, which England was slow to master. Soon after his first successes with adapted French importations, the actor-manager began also to mount locally written and composed pieces put together in the vein of the French hits. And thus, one could simplistically say, were the first ‘Viennese Operetten’ brought to the stage.

Like France, Vienna began small – with successful pieces such as Suppé`s Das Pensionat (1860), Zehn Mädchen und kein Mann (1862), Flotte Bursche (1863),and Leichte Kavallerie (1866),which belonged to the politer French genre rather than the opéra-bouffe, and such as Die schöne Galathée (1865),which took a tentative step towards the bouffe arena. There were a few attempts to mount a full scale opera-bouffe – direct burlesques of Lohengrin (1870),, Dinorah (1865),and other operas – but, by the time the 1870s arrived, France itself had deserted the wonderful extravagances of the Empire stage for things less zany and less exciting: the well-made opéra-comique was taking the place of the inspired musical foolery of opera-bouffe. Lecocq’s La Fille de Madame Angot (1872),Planquette’s Les Cloches de Corneville (1877), and Offenbach’s Madame Favart (1878), would head the next generation of French musical-theatre hits.

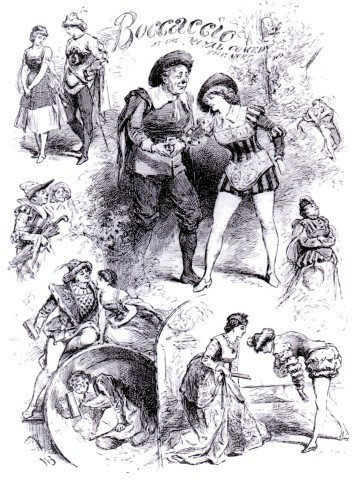

Thus, Vienna did not get its full-scale home-made contemporary opera-bouffe hit, but many elements of the ‘bouffe’ style nevertheless persisted into the best of 19th century European Operette. Not least, a paler but still interesting version of the sexual emphases. When the Hungarian vocalist, Antonie Link (1853-1931), starred in two of Vienna’s outstanding new Operetten of the 1870s as Fatinitza and Boccaccio, she was seen as a boy disguised as a girl of the first, and then as the sexy poet of the title of the second. Not for any purposes of sexual ambiguity, but simply to show off her fine figure and legs to the appreciative gentlemen of the boxes and stalls and a gaping gallery public. And her fine expansive mezzo-soprano to musicians. And Frl Link’s attractions (and of course, her talents) were for no small part in the vast success of the two shows.

Instead of modelling itself on the already dear departed opéra-bouffe, the Viennese Operette stage took itself to another part of the then wholly superior French theatre. Its plays. Almost every successful new Operette to come out of central Europe in the 19th century had French blood in its pedigree, and most often in large doses. The French comic theatre – and even the French opéra-comique theatre, stripped of its original music – provided the basis for the great hits of the nonsensically nick-named ‘Golden Age’ of Viennese Operette.

In fact, that so called ‘Golden Age’ brought forth just a handful of ‘golden’ pieces, pieces which were produced successfully and internationally in their time. Alas, those which made their way to France and to the English language theatres of Britain, America and Australia were almost always as barbarously treated as they are today in the self-satisfied world of Regietheater, and, in the end, only one Viennese Operette of the nineteenth century can be said to have made a truly international success.

Ah, yes, I hear you say. Die Fledermaus.

Contrary to popular myth, Die Fledermaus (1874) was not, in the nineteenth century, an international success. In fact, if figures speak true, it wasn’t even as big a central European hit as some would have us believe. But figures can lie, and that’s not my territory. My territory is ‘overseas’, and in English-speaking areas, in the 19th century, Die Fledermaus came and went fairly unnoticed. In France, it wasn’t noticed at all, as the Viennese authors having ripped-off (word for word in its best parts) a copyright French play for their libretto, it couldn’t even be played on any stage where French copyright laws held sway.

Poster for a “Boccaccio” production in London, 1882.

So what is the 19th century Viennese theatre’s one big, contemporary, international hit? Why, Boccaccio (1879). Libretto allegedly from a French original (or just in imitation of one?) and music by Franz von Suppé. No, not the buzzword hero of 20th century devotees, Herr Johann Strauss. Music by Franz von Suppé. And wonderfully tasty music, too.

Boccaccio was a hit in Vienna, a hit in Berlin, a huge hit in Hungary. It travelled to England where, with the slightly scandalous (but undeniably talented) Violet Cameron in its title role, it scored again. It went to America, it went to Australia and Emily Soldene herself picked it up and toured it round and round … a slightly unyouthful Boccaccio by that time, but evidently as sexy, comical and superbly-singing as ever. In France, the Boccace was Mlle Monbazon, the original Parisian heroine of the even saucier La Mascotte. And everywhere the show was a winner.

Boccaccio had the good fortune, in London, to be taken up and mounted by an exceptionally good producer, Alexander Henderson, sometime husband of Lydia Thompson (1838-1908), the British queen of burlesque and the producer of her vastly popular and advertisedly ‘naughty’ shows on both sides of the Atlantic. For, it has to be said, that up till that time, German-language Operette had been given a strange sort of a go in Britain.

Die Fledermaus, Indigo (1871), Fatinitza (1876) and Der lustige Krieg (1881) had all been produced at the Alhambra Theatre, Leicester Square. In modern terms, one could say it was as if they had been produced in an arena, or on a lake stage, where the visuals were all and the audials, especially anything resembling smart dialogue … very little.

They were also stuffed full of what had now become the traditional Alhambra extras, notably squadrons of little ballet girls (who latterly inherited many of the backstage ‘followers’ of the Philharmonic) doing lots of ‘I can do fourth position’ (and not much more) routines, and showing off their take-me-to-dine-able legs. A far cry from the days when the long-legged Mlle Sara had got the Alhambra closed down for her flamboyantly ‘indecent’ can-can dancing. The sensation-making Sara had gone off to join the wicked Soldene company, and the Alhambra thenceforth made do instead with large effects rather than stunning ones.

Often, too – as in the cases of the London Fatinitza and Der lustige Krieg – the Alhambra productions were culpably under-cast (on the principle, I imagine, that no-one was listening much, just looking), and in The Merry War – from which German singer Lori Stubel was actually sacked for vulgarity on stage — the hugely advertised pièce de resistance of the evening was nothing to do with Strauss’s show, but the interpolated appearance of the German Giantess, Marian, at the head of her troop of Amazons. Or, it was, until, five weeks into the run, when the Alhambra burned down. And that was the end of The Merry War, the Strauss Operette which had – beyond the Atlantic – proved to be the most popular of all the composer’s works.

Die Fledermaus was, after its rather forced Alhambra run, not seen again in London in English for thirty years. However, the 20th century attachment to the name of ‘Strauss’ happily brought it back. If, perhaps, rather too exclusively. For, unhappily, nothing has brought back its more successful contemporaries, Boccaccio and Fatinitza. Nor Der lustige Krieg. Nor my own particular favourite among 19th-century central European Operetten, Karl Millöcker’s Der Bettelstudent (1882).

Poster for the 1956 film version of “Der Bettelstudent”.

Ah! Der Bettelstudent. Which will, of course, be hugely featured somewhere else in this book. So I shan’t speak of its joys, just its history. Like many German works, it was given in Belgium before France, and France didn’t throw any leaps of joy when it was finally given L’Etudiant pauvre at the Théâtre des Menus-Plaisirs. In Britain, where it was mounted, following a considerable success in America’s German and English-language theatres,, it was an Alhambra production, with all that that entailed … but it somehow survived that baptism in vast spaces, and thereafter went round the British provinces – with no special casting — several times with success, establishing itself, behind Boccaccio, as the second most popular Viennese Operette of the era on British stages.

The Alhambra productions, Boccaccio and the odd mishap such as an ill-translated, ill-cast and a very short-lived version of Strauss’s Prinz Methusalem (1877) were all the attention that the German-language theatre got in London of the 1870s and 1880s. The fact, of course, that France was still supplying its near neighbour with vast hits such as Les Cloches de Corneville and La Mascotte, doubtless stopped producers digging for new shows any further afield, but, in fact, each of Austria’s most important contemporary hits was given a London showing. Mostly, unfortunately, under what have to be called ‘unfavourable’ conditions. And, apart from Boccaccio, with consequently unfavourable results. Golden? Not for the British producers and their backers.

But the central European theatre had by no means had its day. In the first part of the twentieth century, Austria, Hungary and Germany would send forth a second and much better-received volley of shows for the musical and theatrical pleasure of its neighbours. A volley which has been sadly christened ‘the silver age’, suggesting it was somewhat less consequent and less successful than its ‘golden’ predecessor. It wasn’t, of course. It was, on an international scale, vastly more successful

And that, very largely, because the great ‘age of export’ got under way with one singularly successful show.

Lily Elsie and Joseph Coyne in “The Merry Widow”, London 1907.

The earliest years of the twentieth century had seen Europe’s new and modern set of musical writers come up with some fine shows. Pieces such as Reinhardt’s Das süsse Mädel (1901), Lehar’s Der Rastelbinder (1902) and Eysler’s Brüder Straubinger (1903) were decided hits at home, and exported happily to other Garman-speaking stages, and to the voracious Hungarian theatres. But it was not until 1905, when Die lustige Witwe – with its elderly French libretto and its soon to be hummed everywhere score — came along that the breakthrough to the English and French language stages occurred.

Like Boccaccio, Die lustige Witwe was fortunate, when its time came, in being taken up for its British production by a skilled and successful producer. George Edwardes had made his name and fortune producing musical plays, mostly of a home-made variety at, in particular, the Gaiety Theatre and Daly’s in Leicester Square. At the Gaiety, he inclined to fluffy, revusical, tuneful, girlie ‘musical comedies’, at Daly’s he staged more romantic, musically substantial (but equally chorine-studded) pieces. At Daly’s, he had premiered the most internationally successful musical play of the British nineteenth century musical stage, — the piece which out-Sullivaned and -Gilberted England’s buzzword team — The Geisha (1896), and followed it with more of the same until squabbles between the personnel involved forced a change of direction. He had done well since with the delicious French Les p’tites Michu with its Messager score (1897), althoughless well with a made-to-order ‘French’ musical Les Merveilleuses (1906)concocted from a libretto by Victorien Sardou and original music by Vienna’s ‘Hugo Felix’. But he decided, nevertheless, to follow the formula and picked another French libretto decorated with music by an Hungarian, but Vienna-based composer. One which had already thoroughly proved its worth in Europe: Die lustige Witwe.

It must be said that the The Merry Widow, London version (1907), was not identical in all its parts to Die lustige Witwe. Following his established formulae, Edwardes upped the low comedy, and expanded the girlie element. But he did so with the composer at his side, and not with the grossness that would later be practised by some producers, notably in America, on the produce of the German-language stage. So London got a fairly accurate Merry Widow and duly showed its gratitude. The show became a fine success at Daly’s Theatre, and while the Widow toured on and on and established itself as the flagship of ‘Viennese operetta’ on the English stage, it launched Edwardes in particular and the British theatre in general on a decade of purchasing and producing musical plays from Central Europe.

Not all, of course, proved as successful away as they had at home. Edwardes produced Straus’s Ein Walzertraum (1908), with much fanfare and failed. It had adapted poorly as a ‘British musical’ and Edwardes had misjudged his casting, Leo Fall’s Die Dollarprinzessin (1908) however gave him another hit, and the same composer’s Die geschiedene Frau (1910) an even bigger one, rivalling even the Widow with the number and lengths of its tours, Lehar’s Der Graf von Luxemburg yet another (1911).

And not all, in spite of the facile term, were ‘Viennese operettas’. From Budapest came Viktor Jacobi’s Leanyvasar (1911) to triumph at Daly’s Theatre, from Berlin came Jean Gilbert’s Die keusche Susanne (1910), to rival Die geschiedene Frau.

And then it was 1914.

With the onset of the war, with Jean Gilbert the musical hero of the hour and with Edwardes and others with their hands full of Possen and Operetten preparing to flood the country, German music and German shows were in a minute non grata in British theatres.

Composer Jean Gilbert. (Photo: Stefan Frey Archive)

When the war was done, the central European musical pieces began to return to the London stage which they had a few years earlier dominated. There were decided hits still to be drawn from the well in the changed world —Jakobi’s Hungarian Szibill (1920/21), Gilbert’s German Die Frau im Hermelin (1919),andFall’s Madame Pompadour (1922), Austria’s wartime pasticcio Die Dreimäderlhaus (1916), and Gilbert’s Katja die Tänzerin (1923), — but too many Continental triumphs – from Die Csardasfurstin (conversely an enormous favourite in France) and Die Rose von Stambul (1916),, from Grafin Mariza (1924) to Der Orlow (1925) and Der Land des Lächelns (1929) – performed disappointingly on the English side of the Manche.

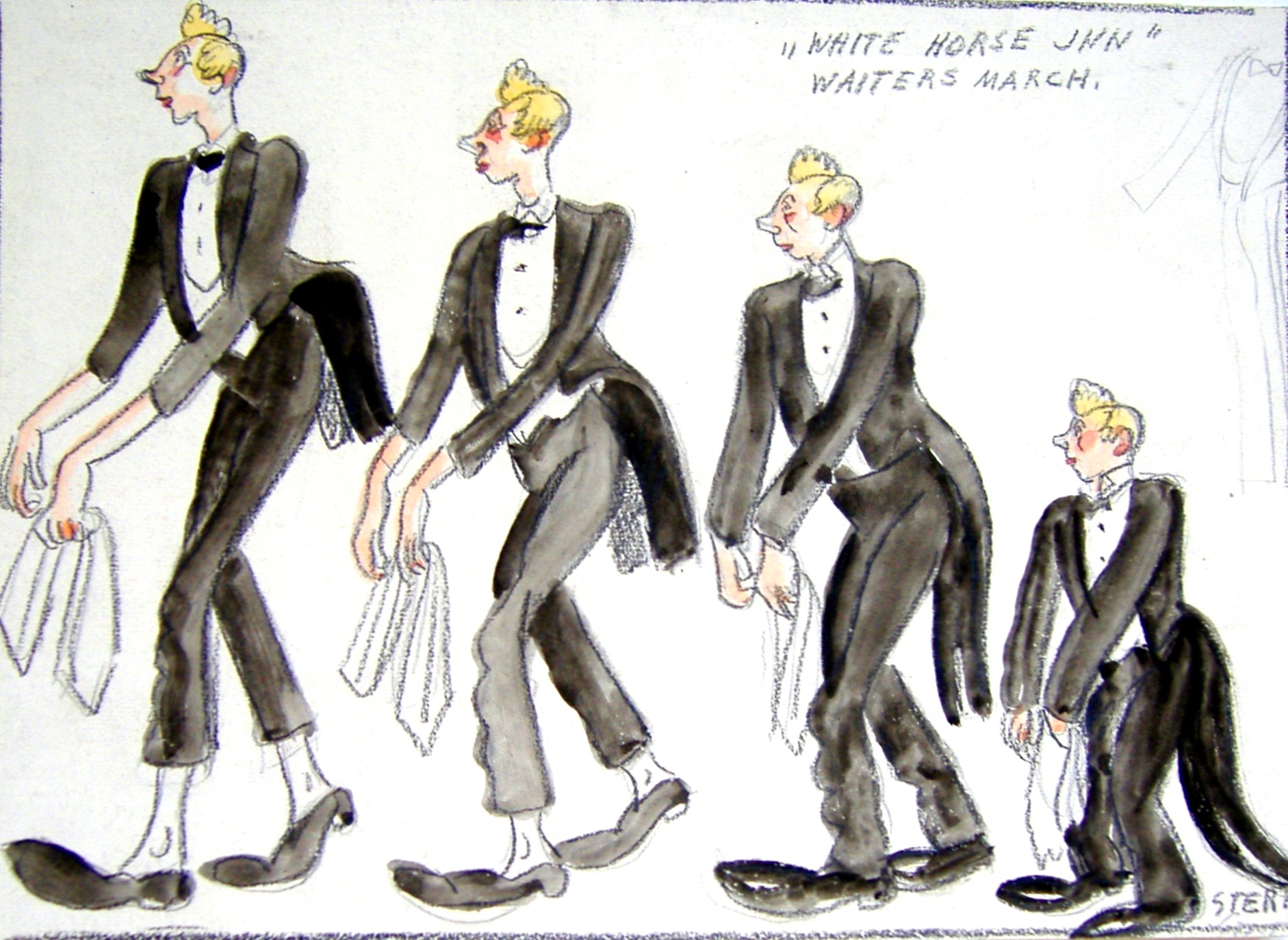

The Continental shows had to share, now, the stages they had for a decade they had made their own. Some triumphed, some sank, but up till the 1930s, still they came. The last hurrah came with two 1930 pieces thoroughly unlike the ‘Posse’ style of piece of the Die geschiedene Frau type of pre-war success: the grandiose Strauss family pasticcio Walzer aus Wien (1930) and the spectacular Berlin “Singspiel” or Revue-Operette Im weissen Rössl (1930)

It was a fitting finale. With White Horse Inn (London 1931, New York 1936) and L’Auberge du cheval blanc (Paris 1932)the German language stage had its biggest and most enduring international hit since The Merry Widow and La veuve joyeuse.

From every tradition, only a handful of pieces will normally survive into repeated productions round the world in the decades and centuries ahead. And even fewer in the commercial theatre. In my life time, I have seen versions of Walzer aus Wien in French and English and missed The Merry Widow in the West End. In the non-commercial theatre, more survive. When I went to Hungary, I had a festival. At Vienna’s Volksoper I enjoyed a Walzertraum, a Bettelstudent and a was disgusted by a denaturised Boccaccio, in the French provinces I caught La Princesse Csardas, in Germany, of course, subsidised houses offer an often enterprising selection. But in English?

The march of the waiters, from “White Horse Inn”, as seen by Ernst Stern in 1936 for the Broadway production of “Im weßen Rössl”.

Only in a handful of specialist and usually subsidised theatres and companies are you likely to see anything but repeated Merry Widows, Fledermauses and the occasional Csardasfurstin, and even those more often in opera houses and with operatic vocalists and stagings, where the management is trying to recoup the losses of the most recent unpopular opera.

But ‘Viennese Operette’ had a fine moment in the international sun, and it left a mark on the world’s musical theatre history that endures three quarters of a century on, far beyond the banks of the Danube and the Spree.

[1] Emily Soldene’s infamous Theatrical and Musical Recollections are reproduced along with the story of opéra-bouffe and Operette in Britain and the colonies in the 2-volume Emily Soldene: In Search of a Singer (New Zealand 2007).