Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

14 September, 2014

The Austrian music historian, film director and author Ernst Kaufmann has written a biography of his uncle – composer Bruno Granichstaedten whose estate he inherited in 1979. It’s the first Granichstaedten biography to date; a remarkable book about a remarkable man. He was one of the great jazz innovators of Viennese operetta, together with Emmerich Kálmán. Both were equally at home in the Broadway idiom and in old-fashioned Wiener Lieder. Both had to flee from Vienna after the “Anschluss” in 1938; both ended up in New York. The only difference: Granichstaedten never came back from the USA. We spoke to Ernst Kaufmann about his uncle and his book project.

The cover of the book “Wiener Herz am Aternenbanner.”

Bruno Granichstaedten (1879-1944) was one of the most prolific and successful Viennese operetta composers of the 1910s and 20s, yet no one seems to remember his name today, except in the context of his one-song-participation in Im weißen Rössl (“Zuschau’n kann I net”). Who was Granichstaedten?

Granichstaedten was not only a composer, he also wrote libretti, cabaret texts, film scripts and even stage plays. From the very beginning, the young Bruno was a theatre fanatic. His godfather was Alexander Girardi, probably Vienna’s most famous folk actor. Baron Bezecny, the super-intendant of the Viennese Burgtheater, was also a friend of the family. Bruno had a strong artistic surrounding from the very beginning. After his studies, he wrote for cabarets prior to his career as an operetta composer, and in the 1930s he worked in film, too. He was active in many fields for more than forty years. By the way, the second song to remember his name for is “Da nehm ich meine kleine Zigarette” from the operetta The Orlow.

He comes from a theatre family. His father was Dr. Emil Granichstaedten, a well-known theatre critic. Bruno had contact with various important composers as a child, who became his teachers.

I’m sure that his most important teacher in Vienna was Anton Bruckner, followed by Salomon Jadassohn and Carl Reinecke in Leipzig. Bruno also had lessons with Hugo Wolf, but Wolf moved very often during that time, so there was neither continuous working with him nor regular teaching.

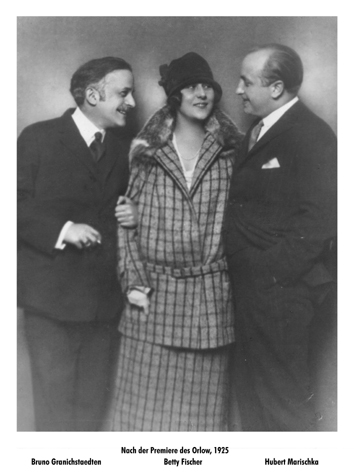

Bruno Granichstaedten together with singer Betty Fischer in 1915. (Photo: Archive Ernst Kaufmann)

Granichstaedten started his career as a conductor of classic music at the opera houses of Erfurt, Mannheim and Munich. His first steps as a composer, though, were in the realm of cabaret – Simplizissimus and Die Elf Scharfrichter. This led to him being fired by the Munich Court Opera. Why?

First of all, he was repetiteur in the Munich Opera and also at the cabaret. There is no proof of actual compositions for cabaret in Munich. The cabaret was despised by the ‘High Culture’ as dangerous and subversive, especially after Franz Wedekind (later a member of Die Elf Scharfrichter) went to prison for ‘lèse-majesté’.

Bruno returned to Vienna in 1905, where three years later his first operetta, Bub oder Mädel premiered. It’s a show about an indebted Austrian (Fritz) who tries to find a rich American woman (Gwendolin) to solve his financial problems. Considering Granichstaedten’s later career, it’s astonishing that the topic of “America” is already present so early.

America and especially New York fascinated him all his life. I don’t know why, but this love was evident from the very beginning. So it was a really great moment for him when the rights for his first operetta Bub oder Mädl? were acquired by a Broadway producer.

The show was staged under the title The Rose Maid at the New York Globe Theatre in 1912.

Even during his time in emigration– when New York showed him its cold shoulder – he liked being there, though his last wish was to be buried in Vienna. So I think he felt home in Vienna but was taken with the thinking and the commercial possibilities of America. It’s a bit like the story of the Russian emigrant Alex in his operetta The Orlow – only the successful ending in New York remained an unfulfilled dream for Granichstaedten himself.

His first major success was Auf Befehl der Kaiserin in 1915, at the Theater an der Wien. It’s a rather nostalgic show about an empress, her philandering husband, court intrigue, imperial soldiers and life in the good old days. Did Granichstaedten write nostalgic music for this?

Bruno Granichstaedten, the 1920s star composer. Autographed postcard from the archive of Ernst Kaufmann.

I think it was the right time for that topic. The emperor was old, the monarchy was in its twilight years, people suffered from the war and many yearned for an idyllic world of yesteryear. The music Granichstaedten composed underscores this feeling by being rather traditionally “Viennese.” The whole operetta is written as a kind of consciously old fashioned Wiener Singspiel.

On the other hand, his most famous work, in 1925, again at the Theater an der Wien, was Der Orlow – a jazzy tale of a poor Russian aristocrat named Alex Doroschinsky who is now working as a car mechanic in Chicago. He has lost his fortune during the Revolution and was only able to save a diamond called “The Orlow.” Why was that show such a hit in times of inflation and depression in Vienna and elsewhere?

Basically, it was the music. Jazz had been brought to Austria from America and England: this completely changed the musical style of operetta and popular music in general. Granichstaedten’s “Für Dich, mein Schatz, für Dich” from The Orlow was the first blues song in a Viennese operetta. It was also the first time saxophones were used in a Viennese operetta orchestra.

Granichstaedten actually went to the US in the 1930. What did he do there?

He was engaged by Sam Goldwyn to write – together with Nacio Herb Brown – the songs for the Hollywood film One Heavenly Night. He returned home because he felt that his work for the European theatre was more important for him.

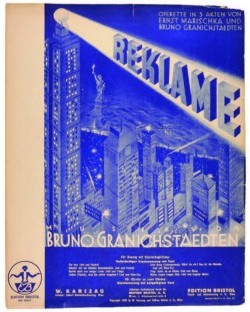

Does his 1930 show Reklame (Der Dollar rollt!) reflect his first-hand experiences from America?

I think this was not his plan, but there certainly are many noticeable influences.

Were his American-themed shows played on Broadway or in London?

Yes, The Orlow was staged at the Strand Theatre in London in 1926 under the title Hearts and Diamonds.

Sheet music cover for the 1930 operetta “Reklame.”

What was his relationship to the other “modern” operetta composers of his time, Kálmán, Oscar Straus, Ralph Benatzky or Paul Abraham – many of who copied his jazz experiments?

They were just colleagues – for Straus he wrote the libretto for Die Königin and for Benatzky’s Im weißen Rößl the song “Zuschau’n kann ich net”. The only one who came to his funeral in 1944 was Emmerich Kálmán, even though all the others mentioned above were in New York at the time too.

Granichstaedten has a Jewish background, which turned into a major problem after 1933. Did he self-identify as “Jewish”?

He was from a Jewish family but was baptized Roman Catholic and considered himself an “Austrian.” He never talked about politics, and even in 1937 – on a visit to England – he couldn’t believe that he would be of any interest to the Nazis: so he refused to stay in London, and returned to Vienna, which was a big mistake.

Granichstaedten’s last operetta, “Sonili,” performed in Luxemburg in 1939. (Photo: Archive Ernst Kaufmann.)

Via a set-up engagement in Trier – of all places – he managed to escape in 1940 via Luxemburg to New York, with his second wife Rosalie Kaufmann, your aunt. Can you tell us how they met, and how they got out of Nazi Europe?

(laughs) This is what half of my book is about. The short version is that Rosalie was the daughter of Bruno’s commanding officer during World War I. Bruno met Rosalie in her father’s house in Vienna in 1935. She was a singer, and they fell in love right away.

After the Nazi’s occupied Austria in 1938, Bruno and Rosalie managed to escape from Trier to Luxemburg by going over the river Sauer at night.

The whole family was ripped apart – Bruno’s son from his first marriage was taken to Auschwitz by the Nazis, where he died in 1943; his daughter from the first marriage escaped to Florida; his first wife stayed in Vienna.

How did he himself spend his last four years in America?

He tried to gain ground in New York, but he failed. He managed to get some songs performed at local radio stations, but there were no work offers from theatres or film studios. Rosalie sang at the Grinzing, a well-known restaurant at that time with cabaret acts and little shows. They received financial help from the opera singer Maria Jeritza who lived in New York and supported many Jewish artists.

The dazzlingly beautiful Rosalie Granichstaedten. (Photo: Archive Eernst Kaufmann.)

After the war, your widowed aunt decided to stay in America, rather than return to Europe like most operetta composers and their wives. This had serious effects on Granichstaedten’s status as a composer. Why did your aunt not want to secure a spot in the post-war operetta scene for her husband?

Because of her traumatic experiences in the camps between 1938 and 1940, before their escape to Luxemburg, it was never an option for my aunt to return to Vienna and to live there permanently. When Bruno died, Rosalie was only 34 years old, certainly full of plans. She was busy with her own life. She made a solid career as a singer in New York’s night clubs in the late 40s and 50s. In 1955 she opened her own restaurant named Rosalie’s Gloriette which she ran until 1963.

She then retired to Florida, where she lived until she died in 1979.

Were there any important Granichstaedten productions in the 1950s or 60s?

Yes, and as far as I know both in Vienna: Der Orlow at the Raimundtheater with Jopi Heesters and Margrit Bollmann in 1959 and at the Volksoper with Eberhard Wächter and Irmgard Salemka in 1963.

You met your aunt every year, as a child, when she came to Vienna. And you heard many stories from her. What fascinated you about these stories?

First of all, it was her enthusiastic talking about Bruno, his behaviour and his work that caught my attention. The picture I got was that of a restless man, driven by his ideas and working in many fields – writing, directing, drawing stage design and costumes … As a child I thought: Hey! Let me have such a great and creative life, too.

Film director and book author Ernst Kaufmann, nephew and biographer of Bruno Granichstaedten.

Years later, when I realized that the reality of an artistic life is quite different and means missing out on lots of other things, I was caught up in the beginning of my career as a film director. But until today I don’t regret anything.

In 1979, Rosalie left you the Granichstaedten estate. What was in that estate? What did Rosalie intend for you to do with it?

It consists of some hundred pages of his music scores, some typed scripts, his beloved old type writer, personal things like rings, watches, pens, and a lot of photographs and newspaper reviews. At that time I had already started studying music and Rosalie knew that my interest in music history was partly triggered by her stories. So she felt I would be the right person to keep Bruno’s name alive.

In 2014 you published your book Wiener Herz am Sternenbanner, a biography of Bruno Granichstaedten. It’s written like a novel, which is unusual for an academic biography. Why did you make that choice?

From the first moment when I had the idea to write a biography about my uncle, it was very clear for me that it will be based on the stories in my mind. Because I want to make people feel for him and his personality, understand his great success and his deep fall.

And I wanted it to reach an audience outside the academic field.

There are many atmospheric descriptions. Are they fictional?

They are mainly based on the stories of Rosalie and other family members I interviewed during my research for the book. Some of the scenes are dramatized to reflect the atmosphere of the time and Bruno’s disposition.

Bruno Granichstaedten with the stars of the 1925 worl-premiere of “Der Orlow.” (Photo: Archive Ernst Kaufmann)

Where does the book title “Wiener Herz am Sternenbanner” (Vienna Heart at the Star Spangled Banner) come from?

It refers to the fact that Granichstaedten, aside from his love for America, always remained a boy from Vienna at heart.

Considering how much US history is involved in Granichstaedten’s life, are there plans for an American edition of your book?

No fixed plans, but naturally it is a great wish. Currently, I am doing my best to promote the book in Austria and Germany, because normally you have to generate substantial sales here in order to gain any interest from an American publisher.

Are there any current performances of Granichstaedten works, anywhere? Which show title do you think should be revived? And why did Jonas Kaufmann on his new operetta CD – devoted to the 1920s – not sing the famous “Zigarettenlied”?

As his music rights are with his grandchildren in America, I don’t know about the actual performances. And Jonas Kaufmann might have thought the “Zigarettenlied” was the song of Jopi Heesters – and no one can sing it better. (laughs)

Where is the Granichstaedten estate now – is it publicly accessible for operetta researchers?

Granichstaedten’s still existing music scores and typescripts are available for research at the Wiener Stadt- und Landesbibliothek in the Vienna town hall. All his personal things are in a memorial room at the Bezirksmuseum Landstraßein Vienna’s third district where Granichstaedten was born.

Last question: will there be a film version of your book?

Hopefully yes, I already started with a first draft for a screen play.

what an extremely well written and nicely researched article, thank you – also for the most interesting interview with the attractive mr. kaufmann. gh

I certainly hope that a film version will be made of this book. It is a fascinating story and George Clooney with a moustache would be my first casting choice.

Scarlett Johansson: please be his Rosalie!

Ernst, hello wanted to let you know I was able to read this today 3/28/15. Bruno is my Grandfather and my sister Monica lives in Florida. Very interesting reading and some information that I never knew about Bruno. I would like to talk to you one day, we will have to figure out how to make contact.

David

Ernst, i read your story above and I am a granddaughter of Bruno. There are a few items left out but they might be in the book. I have some music of Bruno that your aunts caretaker sold to us many years ago.

I along with my brother would love to talk to you oneday.

Thanks, Monica

We have forwarded both your messages to Ernst Kaufmann and hope he will get in touch with you. Thank you for your comments!

Hallo,

I search for the Operetta “SONILI” from 1939, that was wrote in german language by Bruno Granichstaedten and translate in Luxemburgish by Josy Imdahl. I have no Text and no Music about “SONILI” If sameone has Text or/and Music about, please contact me by mail. Thank for all help. (answer , if possible, in german or frensh)