Richard C. Norton

Operetta Research Center

2 September, 2015

In their 2015 summer season, the Ohio Light Opera presented the original stage version of Cole Porter’s Can-Can. It’s a show that in many ways evokes the world of French operetta and of Offenbach, but tells the story in a decidedly different way. Broadway historian Richard C. Norton was invited to Wooster, Ohio to give a lecture on Can-Can. He has allowed us to reprint his text.

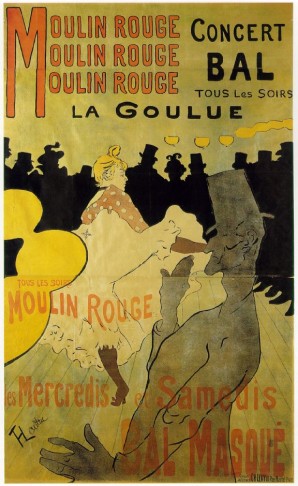

Moulin Rouge: La Goulue, poster by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1891. (Photo: Wikipedia)

I think it is safe to say that we all think of the much-loved musical Can-Can today as “Cole Porter’s Can-Can.” Truth be told, it was not always thus. The inspiration for what became Can-Can in fact originated with its producer Cy Feuer, whose WW2 military duty took him to the famous ‘city of light’ in the mid-1940s. Upon his return to the USA it was his idea to produce an American musical set in the Paris of Toulouse-Lautrec in the 1890s, perhaps with Henri Toulouse-Lautrec or the famed dancer La Goulue as its subject. After the success of Guys & Dolls in 1950, Feuer & his co-procuer Ernest Martin redoubled their efforts to create an authentic Parisian musical for Broadway audiences. Cy Feuer very simply called up Porter and asked him if he’d like to write the score.

While Porter was considering the offer, Feuer & Martin asked Abe Burrows, with whom they’d collaborated happily on Guys & Dolls if he’d be willing to write a musical called Can-Can set in Toulose-Lautrec’s Paris in the 1890s; Burrows initially balked. He’d never been to Paris, indeed never traveled outside of the USA; what did he know about Paris? F&M sweetened the deal by agreeing to send Abe to Paris for a couple of months for research. Burrows still couldn’t imagine himself writing dialogue for French characters to speak in English; oh, and F&M wanted Abe to direct. Burrows had liked working with F&M on Guys & Dolls, as they all hailed from the same part of Brooklyn, and they understod one another. “Who’s gonna write the songs?,” Burrows asked. When they said Cole Porter, Burrows gasped “Why didn’t you say so?.” They answered “we were saving the clincher in case you were in doubt.” Also on board was Michael Kidd whose choreography had proved so essential to Guys & Dolls’ success.

Burrows recalled his collaboration with Porter in a 1959 interview: “He would call at odd times, once at one in the morning. ‘Abe,’ he’d say, ‘Here’s how it ought to go. Pom pom pom pom pom pom pom pom pom.’ And he’d hum the thing. I once started to hum along and he stopped me sharply. ‘Don’t hum.’ So I shut up and he gave me the rhythm of the song. That’s how he did it. He would think up the rhythm. Then he would write the words to fit the rhythm and then he’d write the music to fit the words. Once he had it, that was that. He wouldn’t change a waltz into a beguine. He didn’t work like that. He’d look at you calmly and say, ‘I’ll give you another,’ but he wouldn’t change that one. He wouldn’t bend a song. Songs get bent and changed and ruined.

“But he could also come up with a song in a tight spot. There was a moment in Can-Can when the hero and heroine have split up. He’s at a café table and a very attractive prostitute comes over and sits down next to him. At first, he tries to wave her away, but then in my first draft he says, ‘I’m sorry, Miss. This is the wrong time and the wrong place. But you are charming so [he shrugs] I guess it’s all right.’ Cole gave it some thought and came up with a song; ‘It’s All Right with Me’ was one of his best. It was funny, Cy Feuer, Michael Kidd and I had gone to the same high school in Brooklyn and we all talked like it. Cole was from a different world, but he really liked being around us. He just seemed to enjoy himself no matter what. Despite the pain, he always loved the work.’”

(left to roght): Michael Kidd, Lilo, Ernest Martin. Front, left to right: Cy Feuer, Porter, Abe Burrows. Of the two men above right, the heavier is Jo Mielziner. (Photo: Archive Richard C. Norton)

Any show with a title like Can-Can was expected to be a dance show. So just exactly what were the origins of the can-can? The can-can originated as a social dance for couples in the working class dance halls of Montparnasse in the 1830s, whether French or Algerian is open to dispute. The words “can can” mean literally tittle-tattle or scandal, its alternate title “chahut” means noise or uproar. As its poularity spread, it was adapted for music halls, revue and opera comique, most famously by Offenbach for his “Infernal Galop” in Orpheus in the Underworld in 1858. By then it had evolved somewhat.

Typically danced by four women clad in long skirts, petticoats and black stockings, it was both highly athletic and fast-paced. It included several specific dance steps: (1) battements, or high kicks (2) ronde de jambe, a quick movement of the lower leg with the knee and skirt raised, (3) port d’armes, the rotating on one leg, meanwhile grasping the other leg at the ankle, held up vertically, (4) cartwheel, and (5) grand écart, a flying up, then landing in a jump split. Typically, screaming and yelling are optional, and modern variations include backflips in addition to the traditional cartwheels. The final gesture (6) has the girls bend over, to flash their backside underwear to the audience. La Goulue famously had a heart sewn to the seat of her underwear. The can-can, contrary to Abe Burrows’ libretto, was seldom considered lewd or obscene, but Paris in the 1890s (like every era) had its fair share of moral crusaders trying to regulate social conduct and theatrical performances. Can-can dancers were not prostitutes, but their youth and undeniable athletic prowess attracted many male admirers who sought their personal favor.

Gustave Doré’s vision of the „Galop infernal“, as seen 1858 in Paris.

Porter was suffering from a prolonged depression in the early 1950s, although it is difficult for us today to appreciate just why, since he’d just scored the biggest hit of his career with Kiss Me, Kate in December 1948. Consequently so much more had been expected of Out of this World, his musical adaptation of the Amphitryon legend, conceived in collaboration with Agnes de Mille in December 1950. Not even a late tryout assist from George Abbott as replacement director could spare the show from a disappointing four-month run. But the root causes of Porter’s depression were many and complex, beginning with the lingering pains from frequent surgery following his horseback riding accident of 1937. But the pre-war world of Broadway-London-Paris that had once been his personal playground had been irrevocably changed by the war. And the musical comedy theatre for which Porter had devised star-driven vehicles like Anything Goes, Something for the Boys, Panama Hattie and Mexican Hayride had been usurped by the arrival of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s serious musical plays, Oklahoma!, Carousel, South Pacific and The King and I. This marked a new era, and a new template for musical theatre. Porter’s worst fear was that he’d become a relic, and his musical style disparaged as “old hat.” Porter was not one to originate a musical project; he had to be asked, and often the credentials of producer, star, subject and librettist had to be vetted first as “top drawer.” One hugely significant cause of Porter’s depression was the sudden death of his mother Katie on 2 August 1952, back in Peru, Indiana. Summoned to her bedside, she passed before he arrived. It is hard to believe, but his biographers all agree that Porter wrote these giddy lyrics that week on the veranda on the family home:

“There is no track to a can-can,

It is so simple to do,

When you once kick to a can-can,

‘Twill be so easy for you.

If a lady in Iran can,

If a shady African can,

If a Jap with a slap of her fan can,

Baby, you can can-can too.

If an English Dapper Dan can,

f an Irish Callahan can,

If an Afghan in Afghanistan can,

Baby, you can can can too.”

Compounding his grief at the same time was the prolonged decline, confinement of his wife Linda. Bedridden, she was unable to attend the Can-Can opening on 7 May 1953, but sent Cole her traditional opening night gift, an inscribed gold cigarette case. She died one year later on 20 May 1954.

While it’s safe for us to say that Cole Porter sought solace, comfort and consolation in his work, it is difficult to reconcile with the buoyant gaiety of Can-Can’s story. But look for clues in his work. Consider the underlying sadness of Porter’s music and lyrics to “Allez-vous-en;” or, the regret of “It’s the wrong time, and the wrong place, your lips are tempting, but they’re the wrong lips” in “It’s All Right with Me,” or even the fierce, if lonely bravado of “I Love Paris.” Cole Porter took his commission/assignment very seriously. He studied French popular music of the 1890-1920s, the culture of café conc and French music hall in which Can-Can is set. Even if Abe Burrows libretto is at times more Broadway than it is authentically French, Porter suffused his score with thematic allusions to the Paris of Yvette Guilbert, Jacques Offenbach, and peppered his lyrics with French language and idioms.

I don’t think any other American songwriter would have been better equipped to write the score. Cole Porter first visited Paris in 1908, when he no doubt sampled its famed cabarets. Cole and his wife Linda spent much of his youthful 1920s holding court in their Paris salon for the rich and famous. In 1952-3 Porter returned to Paris briefly for the first time since the war, and returned swiftly, discouraged by what he found. And yet his score to Can-Can is a personal love letter to Paris. If operettas and musicals of the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s were frequently set in Paris (think of Porter’s own Fifty Million Frenchmen in 1929), few had been since. In the years that were to follow, think of Fanny from 1954 set in Marseilles, the film of Gigi in 1958. Americans had just begun returning to Europe in significant numbers in the early 1950s, as jet travel reduced the trans-Atlantic travel time from twelve to seven hours. Alan Jay Lerner, Gene Kelly and Vincente Minnelli had re-launched America’s obsession with Paris with their Gershwin confection An American in Paris, which captured the Academy Award for Best Film in 1951. And John Huston’s film Moulin Rouge opened in December 1952 to much acclaim, starring José Ferrer, Zsa Zsa Gabor and Colette Marchand, telling a fictionalized story of the bohemian life of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

As for Abe Burrows’ Can-Can, La Môme Pistache runs a French music hall by night, and her dancers are nominally “laundresses” by day, with a nod to propriety. When Judge Aristede is confronted by charges of indecency, he visits the Music Hall to see for himself. It should come as no surprise to you that he is won over; song, dance, and the fair female sex always win out over the tiresome, self-appointed guardians of moral decency.

The sheer sexiness of “Can-Can” was a large part of its appeal in 1953. Even if the audience never saw any nudity, Cy Feuer described in detail how Michael Kidd created its illusion.

As the male dancers slid across the floor underneath the girls’ legs, they emerged brandishing pairs of saucy underwear. It looked as though the men had snatched the ladies’ drawers. As Cy Feuer observed, it addressed the conceptual problem of how to show a modern audience what the indecency issue was about, without actually showing them anything. Ah, the illusion of musical theatre! In the self-consciously prudish era of the Eisenhower administration 1952-60 and the witch hunts of the House Un-American Activities Committee, Can-Can was deemed such a naughty, sexy show, that Los Angeles Civic Light Opera president Edwin Lester declined to include it as part of his annual subscription series.

Porter was instantly drawn to the very subject of Can-Can, namely its battle against prudishness and censorship, which he had wrestled with for more than thirty years of his career. Many early Porter songs were banned from radio airplay, most famously “Love for Sale” written for The New Yorkers in 1930. Many Porter lyrics were sanitized for recording purposes, noticeable only if you compare them to a live or nightclub or theatre performance, or even the published sheet music. But Porter knew how to write about love and sex better than any of his Broadway counterparts. Think of “Let’s Do It” from Paris (1928), “Love for Sale” or “Just One of Those Things.” If a song did not work, he’d throw it out and write an altogether new one. And even second-drawer Cole Porter is better than a lot of what passes for Broadway’s best, whether in 1953 or now.

Listen to Cole Porter himself sing several songs that were dropped from the score. “When Love Comes to Call” obviously presages the better-known “C’est Magnifique.” Consider his “To Think That This Could Happen to Me” or his “What a Fair Thing is a Woman.” Listen to the demo of “I Do” and you’ll hear a tune Porter later re-used.

Can-Can did not have an easy gestation, nor did it win unqualified critical acclaim upon its premiere. Mixed reviews in Philadelphia, particularly for its book, sent the creators back to frantic fixing. But from the very start, the show was a sell-out hit with the public. The story of its New York opening is well-known to all, and many of you in this room, for it made Gwen Verdon an undisputed star in the featured role of Claudine. Her appearances in the Apache Dance and the Garden of Eden Ballet became the stuff of legend. But the star was supposed to be Lilo as La Môme Pistache, whom producers Cy Feuer and Ernie Martin had discovered on a trip to Paris, where she starred opposite Luis Mariano in Le Chanteur De Mexico. Problem was, Lilo didn’t speak English, and she memorized her lines by rote. Unhappy with her rival Verdon getting too much attention, it is rumored that Lilo complained to the producers, and Verdon’s role in rehearsals and tryout was prediactably trimmed; wags dubbed it “the Battle of Verdun.” Lilo was not a dancer, and it was more her style to declaim her songs, as in her most famous solo “I Love Paris” and her duet with Cookson, “C’est Magnifique.” This lack of spontaneity in her performance didn’t fool the critics. Her co-star Peter Cookson as Aristede had no previous musical experience, so you can imagine the lack of chemistry between the two leads. So it was left to Cole Porter’s score, Michael Kidd’s reckless athletic choreography, led by Gwen Verdon, and the comic antics of Erik Rhodes, Hans Conreid and their crazy artist friends to usurp the show.

Gwen Verdon on the left, Porter at piano, includes Hans Conried at right, Erik Rhodes (thin mustache) at left; man in center unknown. (Photo: Archive Richard R. Norton)

What hurt Cole Porter most of all was that his score was not better appreciated by the critics at the time of its first hearing. Even before the show opened, Porter promised Feuer & Martin his score would be disparaged as not up to his usual. It was widely condemned as “second-rate” Porter. What artist wants to compete with himself, compared to the score of Anything Goes he wrote 19 years before, or Kiss Me, Kate 5 years ago? But Porter’s hit songs to Can-Can were covered quickly by every major artist of the day, Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Judy Garland, Bing Crosby, Nat King Cole, Peggy Lee, Gordon MacRae, Kay Starr, Maurice Chevalier, to name but a few. Porter was further dismayed that the French government never acknowledged what he had done to promote French culture. Imagine the stampede of American tourists who flocked to Paris in the 1950s in search of the Folies Bergere, Montmarte, the Eiffel Tower, the Champs-Élysées, trying to find for themselves Le Bal du Paradis and the legendary settings of Can-Can.

Can-Can was every bit a hit in London as well in its 1954 premiere at the Coliseum with Irene Hilda starred for a 396 performance run. British theatre historian Rex Bunnett points out that the role of Claudine has often been a star-making role: First Gwen Verdon elevated to stardom. Then Gillian Lynne from London’s Can-Can went on to choreograph both the original productions of Cats and Phantom of the Opera; and London’s 1988’s Claudine, Janie Dee, is now one of Britain foremost actresses in drama, musicals, film and tv.

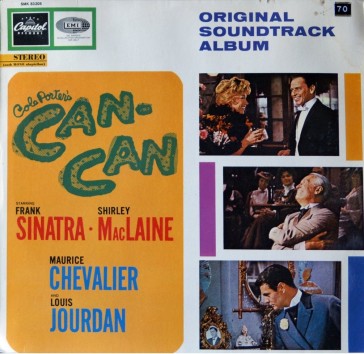

20th Century Fox botched its film version in 1960 with Shirley MacLaine (as Simone Pistache) and Frank Sinatra (in a new role as François Durnais) its not-at-all French leads, despite the inclusion of Louis Jourdan (as Philipe Forrestier) and Maurice Chevalier (as Paul Barriere) to add a note of French authenticity.

For this you may thank director Walter Lang, and screenplay writers Dorothy Kingsley and Charles Lederer. Lang’s work was described as “journeyman” in the packaging of the film’s dvd re-issue, his best credits being the original State Fair, There’s No Business Like Show Business and The King and I. Kingsley penned the screenplays to Kiss Me, Kate and Pal Joey; Lederer is remembered fort the original 1931 The Front Page, its re-make as His Girl Friday, and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Jack Cummings was the lead producer; for MGM He had produced Seven Brides For Seven Brothers but also 3 Cole Porter hits, Born To Dance, Broadway Melody Of 1940 and Kiss Me, Kate before joining Fox.

Cover for the original film soundtrack of “Can-Can”. (Photo: Archive Richard C. Norton)

Frank Sinatra co-produced the film and required several changes. He demanded and got himself a new starring role as François Durnais, an unscrupulous attorney for La Môme Pistache and Le Bal du Paradis. Surprisingly the spectacle of two men competing for Pistache’s affection helps the narrative tension. But it’s no surprise when Sinatra’s character wins the girl at the end from Jourdan’s more staid Forrestier. No fool MacLaine, she’d learned from Lilo’s mistakes. She made certain that the role of Claudine (played by a young Juliet Prowse) was made smaller, and that MacLaine herself got the lion’s share of the singing and dancing. All too obviously staged and filmed on Fox’s backlot, Can-Can might have benefited from the authenticity of a location setting, and French actors in the two key roles played by MacLaine and Sinatra. The film interpolated three Porter chestnuts, “You Do Something to Me”, “Let’s Do It,” and “Just One of Those Things.” They cut two major ballads, “Allez-Vous-En, Go Away” and “I Am in Love.” And three perhaps lesser titles, “Never, Never Be an Artist,” “Never Give Anything Away” and “Every Man Is a Stupid Man.”

One amusing footnote about the film: during a brief thaw in cold war relations, Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev was invited to tour Hollywood, and Fox staged a rehearsal of several musical numbers on 19 September 1959. Chevalier and Jourdan sang “Live and Let Live,” Sinatra did “I Love Paris,” and Shirley MacLaine and Juliet Prowse and the female chorus danced the title song. Later asked by the press what he thought, Khrushchev answered, “Immoral. The face of humanity is more beautiful than its backslide.” And what a publicity coup that proved for 20th Century Fox!

While the film feels synthetic today despite its starry cast, its DVD re-issue does include some rare silent bootleg film footage of Gwen Verdon, a genuine delight.

I have had the good fortune to see many Can-Cans. My first was a fascinating if doomed 1981 Broadway revival starring Zizi Jeanmaire which lasted five performances, co-directed by her husband Roland Petit, and Abe Burrows. Poor Zizi, her English was impossible to understand, especially ze jokes which fell flat, ze romance was unconvincing, and ze plot not very funny. And not unlike Lilo, Zizi was no longer a dancer in her prime. Also a dysfunctional West End revisal starring Donna McKechnie in 1988; a radical re-thinking starring the lovely Kate Baldwin, more Irish than French, at New Jersey’s Papermill Playhouse in 2014.

It’s safe to say that the unequivocal best was Encores’ 2004 revival starring Patti LuPone, which hewed closely to the original libretto, but pared the book to its essentials. Unlike Brigadoon, Kiss Me Kate, Guys & Dolls or My Fair Lady, the libretto and score of Can-Can are fair game for revision and interpolation. The Viennese production in 1968 starred Vico Torriani; I leave it to your imagination to figure out just how a male star could headline Le Bal du Paradis and sing “I Love Paris.” And Japan’s Takarazuka production in 1996 boasts an all-female cast.

The original stage version of Can-Can which Ohio Light Opera has so staged is seldom seen, given the size of its cast and choreographic demands. OLO respects the work of its creators, and OLO Artistic Director Steven Daigle did his best with the incoherent book . Musically the production was mostly a joy, aside from Eve Best’s unconvincing La Môme Pistache, neither French, sexy or funny. Jessamyn Anderson’s Claudine was poor, but the men did much better, Ted Christopher making sense of the befuddled Aristide, and Stephen Faulk a most amuzing Boris leading a clacque of self-absorbed delusioned artists.

The OLO season nadir were the two “Can-Can” ballets, The Garden of Eden and Apache Dance, whose unfortunate choreography looked like grade school pageants, embarrassingly unprofessional.

Let’s hear a round of applause for the resilient Cole Porter in 1953, inconsolable upon both the loss of his mother and the steep decline in health of his wife Linda. Some sixty-two years later, we think not of Michael Kidd’s dances, Lilo or Gwen Verdon, but of Cole Porter’s incandescent, witty, tender and lyrical score. It’s Cole Porter’s Can-Can which has endured. If he’s up in heaven, he may just have the last laugh. And he’ll be applauding with us.

When Irving Berlin finally saw Can-Can, he wrote a heart-felt letter of congratulations to Porter, signed “Anything I can do, you can do better.”