Kurt Gänzl

Kurt of Gerolstein (Blog)

20 February, 2016

It is not often that I write about recordings. Since my massive listening-writing effort of The Musical Theatre on Record, it has taken me a long time to bring myself to lend an ear to much recorded music. But this week the world has decided it shall be otherwise. No less than three CDs have popped through my postbox, all three worthy of much more than a background listen.

Kurt Gänzl. (Photo: Private)

They’re three very different pieces of music. One opera, one musical, one choral cantata. One a hit from the 19th century, one only recently written and sung, one still awaiting a first full showing. Two from Great Britain, one from America … but all three, a bit of a miracle in this lazy day and age, wholly original. No ‘based on’ this or that, no pasticcio score and second-hand music: original through and through. So, where do I start? Why not in the order they arrived.

TOADS IN A TAPESTRY

Toads in a Tapestry is the cantata. A form which is sadly neglected, even though largely secularised, these days. This hour-long piece was commissioned to commemorate the 800th anniversary of the signing of the Magna Carta, and was given its first performance, last year, in Faversham, Kent. All I can say is, it deserves annual repetitions, all around Britain, on the fatidic day. It is a thoroughly original and exciting piece for adult and children’s choirs and soprano, alto and bass solo voices (music: David Knotts, text: John Gallas).

King John on a stag hunt. From: Illuminated manuscript, De Rege Johanne, 1300-1400. MS Cott. Claud DII, folio 116, British Library.

The piece is divided into nine ‘numbers’, starting with an atmospheric dawning of the day over Runnymede as the King (bass) arrives, surveyed by his falcon, Gibbun (soprano). The second number (‘I walk on paper’) is sung by one of the day’s main actors: the quill (contralto) which will sign the document, after which we briefly meet the other components (children’s choir and soloists) and the King ponders on what is to come, in the key number of the night (‘Angels sitting in the rushes’).

The Charter is recited and sung, and at the Quill’s urging, signed and sealed, as Gibbun espies the goings-on cynically from a Thames-side willow, in a soprano bravura showpiece (‘Good afternoon, my name is Gibbun’). And when all is signed and done, England goes on being England (‘Song of the People’) and the forest murmers to the end ‘for a tree is partial to a bit of history’ while the choir heads to a great Amen in the most thrilling bit of choral music of the piece.

CD cover “Toads on a Tapestry.”

The live-recorded performance of the Faversham singers is a remarkable one with, in particular, John Alan Ewing singing richly and powerfully as an outstanding King John, but in the end, the reason I am playing this disc for the fifth time, and have ordered copies for my friends, is the cantata.

This is a wholly twenty-first century piece, with its roots warmly embedded in the traditions of English poetry for the people.

The text is true poetry, written with a quirky flair which hardly surprises those who have read a few of Gallas’s many books of verse. Knotts’s music is, I can only say, made for me. The now and the then, melted together into a forever. I got really excited at hearing the vocal lines … from basso profundo to trilling, squealing soprano … none of that ten notes in the middle of the voice rubbish. This composer lets his artists sing.

Anyway Toads in a Tapestry goes into my (very) small collection of ‘play again and again’ CDs, but what I hope most is that it goes into many future productions and … BBC, are you listening?

BZAZZ FROM BIRDLAND

CD cover “Merman’s Apprentice.”

And now for something tooooooooottally different. From an English country church to a most bzazzy bit of Broadway. No, not Broadway today (when did Broadway last bzazz?), this is Broadway in its hey-you day and its got big, big, big and bold, bold, bold and brassy, brassy, brassy boiled all over it. OK? Got it? Well, if you haven’t, you will have when I tell you this new musical (which has been heard several times in concert, only … so far) is called Merman’s Apprentice. Yep, it’s that dame again. And the story is true to title. Little Muriel Plakenstein from Canarsie (Brooklyn) runs away from home to become a Broadway star, and ends up, with the red, hot and blue mama’s help, going on in Ethel Merman’s role in Hello, Dolly. Yes, that’s it. It’s all there needs to be.

You have a song-studded vehicle for a Merman and a mini-Merman (with the occasional interruption from other folk), set in a book (yes, I’ve read it) of showbiz in-jokes and ribbing that will set Broadway fans of all ages a-hootin’ and a-sniggerin’, because this piece has its tongue shoved firmly in its cheeks – somewhere between The Boyfriend and Dames at Sea. But those shows didn’t have two chandelier-cracking leading ladies. Two! Fasten your ear-plugs … here they come!

Ethel, presented with loving kiddery (yes, author Stephen Cole really knew the lady!) is played – well, on the CD, sung – by Klea Blackhurst. Brilliant casting. She has a staunch, scathing, tuneful, yet warm, voice which makes breakfast of her ballads and her ‘Blow Gabriel’ parody, ‘Listen to the Trumpet Call’, is the hit of the night. Little Muriel (who naturally trades in Plakenstein for ‘Lake’) is taken by Elizabeth – daughter of Lara – Teeter. This is the role created by Carly Rose Sonenclar of X Factor fame, but much as I loved Carly, Elizabeth is well-and-truly splendid.

This must be the biggest sing for ‘a kid’ since … since Herbert Hoover put together, and she brings it off with brio.

While the two stars are having a breather, Anita Gillette and P J Benjamin as Ethel’s parents have a funny song about how their daughter became ‘Loud’ and if Bill Nolte looks as he does on the cover, as David Merrick … look no further for the Broadway production!

Because I’m sure this show ain’t gonna stay at Birdland for long.

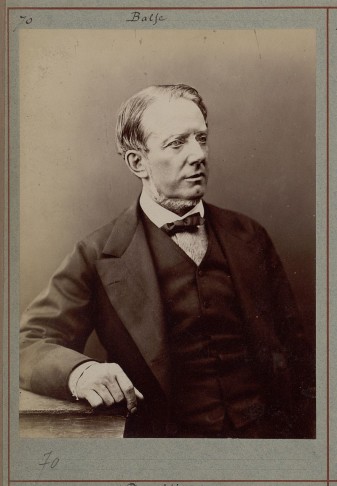

THE POWER OF BALFE

CD cover “Satanella” by Michael William Balfe.

And now for something as different as could be. From both of the previous. I’m not going to give a history lesson here, but this is ‘my’ period, so forgive me if I get a little ‘learned’. Satanella was one of the dozen or so most popular and successful English operas of the Victorian era, of which a disproportionate number were launched by the Louisa Pyne/William Harrison company over a period of just a seven years (The Rose of Castille, Lurline, The Lily of Killarney) from 1857 onwards. A disproportionate number, too, were the work of Irish composer William Balfe (The Bohemian Girl etc), and Satanella shows him at his best, the traditional English opera strains (and dialogue) tempered just enough by his Italian training and experience to produce a score which is one of the most effective, lush and beautiful of the era.

Composer Michael William Balfe.

Victorian Opera Northwest have already given us complete modern recording of Balfe’s previously unrecorded The Maid of Artois and a very fine new Lurline as well as Macfarren’s Robin Hood (another of the top twelve): now, happily, they have turned to Satanella and have, in my opinion, and not just because I like this opera – music and book — the best, topped all their previous efforts in practically every department: recording values, the orchestra under Richard Bonynge, chorus and soloists are all quite superb. I will bet that Balfe never heard his opera sound as rich, flowing and just plain huge as this, even with the superb Miss Pyne and Messrs Harrison (in well-tailored parts) and Weiss singing the leads, in 1858-9, on the stage of the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden.

Selections from Balfe’s opera “Satanella.”

The extremely hit song of the hit show was ‘The Power of Love’ sung by the demoness Satanella to close the first act. No bravura, this, as in The Maid of Artois, but a beauteous, emotional air which went on to be a hugely popular concert item. Don’t worry, the traditional bravura comes in the second act instead, there is a cabaletta to end the third, and a stunning 4th act curtain: quite simply everything any prima donna could ask for. ‘The Power of Love’, and Miss Pyne’s role, are here absolutely splendidly sung by Sally Silver, who we have heard already as Lurline, and she is teamed with a first-rate tenor, Kang Wang, whose sweet and soaring voice is perfect for the demanding sentimental music of the piece’s hero, and whose dramatic passages ring out vigorously and excitingly, in the shining performance of this recording.

The expansive bass role of the fiend, Arimanes, created by the then top bass in Britain, Liverpudlian Willoughby Weiss, is here efficiently sung by a bass-baritone (Trevor Bowes), and the pretty songs belonging to the considerable role of the ingénue Leila, originally played by Britain’s most versatile soprano, Rebecca Isaacs, are delightfully treated by Catherine Carby.

British writers – unlike most Italians of the time, with their inexorably tragic tales – were not afraid to put comic and lighter moments into their texts, and Satanella has its share of these. The comedian/tenor Alfie St Albyn had a sighing swain number which Anthony Gregory delivers in spot-on fashion, and a jolly Pirate, half Enchantress and half Pirates of Penzance, from ‘merry Tunis’,written for another comic player, Henri Corri, here get suitable service from Frank Church. The pure comedy went to singing actor, George Honey (here Quentin Hayes) as a useful tutor who strengthened the bass line when Arimanes was off-stage. The seven principals (Arimanes is off, here) join in a rousingly sung septet with chorus, in the 3rd act, which show Balfe and the forces of Victorian Opera Northwest at their very finest.

This is one of the grandest specimens of English opera, from the era when English-language opera companies were proud to play home-made material.

Scene from “Satanella.”

And that home-made material stood on an equal footing in a repertoire with Lucrezia Borgia, Der Freischütz and Il Trovatore. So why have Satanella and its fellows been allowed to drop from the repertoire? Inverted snobbery? Hopefully, this first-class recording will open the eyes and ears of those who produce English opera. Now that there is a brand new performing text and score available, there’s no excuse for its not finding itself back to the stages of the world in double quick time.

So, three grand CDs, of three pieces looking for performance. I’m sure that none of the three will look in vain or for long. Each, of its kind, deserves to be heard. Again and again. And after a whole morning listening to the soaring strains of Satanella, I’m going back to the start all over again … here we go: Toads number 6 ….

To read the original article, click here. To order Toads on a Tapestry, send an email to the composer: info@davidknotts.com

unfortunately there are NO dialogues recorded in the new satanella – and I find that an acute draw-back as it sabotages the genre and reduces the musical offerings to a nice platter of operatic dishes, a sort of revuewith no coherance. even though the libretto can bedownloaded I find this typical bonynge. he did the same with the soso bohemian girl on decca. its like fidelio or zauberfloete without texts and very much like operatic highlight-lps of the fifties. a missed chance. dialogue was the trademark of british opera of the time. too bad for an otherwise nicely executed recording. hs

Yes, that’s a big drawn-back: that opera fans today seem to think dialogue is not important, and that many opera singers are incapable of dilivering dialogue in an interesting way. (Not to mention many operetta singers.) I guess this has to do with the fact that we are living in an age of deconstruction where “plot” has become irrelvant for many professional theatre people, mostly in Germany and Austria. While at the same time, Hollywood blockbusters and grand TV series are successful because of their novel ways of story-telling. Mad world!