Hans-Dieter Roser

Operalounge.de / Operetta Research Center

20 July, 2020

Anyone taking a close look at the oeuvre list of Franz von Suppé (1819-1895) in search for an opera entitled Il Ritorno del Marinaio will not find anything. In 1885, the year of the supposed world premiere, you’ll only discover Suppé’s last opera Die Heimkehr des Matrosen which opened at the Hamburger Stadttheater, then under the direction of Bernhard Pollini. So, as much as I am thankful that the record company cpo has made this little known Suppé work available on CD, I cannot help but wonder why they didn’t issue the original German version, but an Italian translation?

Suppé’s Romantic opera “Il Ritorno del Marinaio,” recorded in Rijeka. (Photo: cpo)

Mr. Pollini might have hoped for a sort of Flying Dutchman. However, the work was not successful at the Hamburg premiere. It didn’t even make its way to Vienna where Suppé was held in the highest esteem. The only place where his Matrose did stir interest was in Suppé’s Croatian homeland, then part of the Habsburg Empire.

The piece is set in 1816 Lesina, the present day city of Hvar. During Suppé’s lifetime an Italian translation was begun, it’s actually part of the handwritten score. But that score only survives – in full – as a piano version in Cranz. It includes the Italian title Il Ritorno di Mariaio.

Franz von Suppé, in 1885.

While the 200th birthday of Franz von Suppé in 2019 has hardly been celebrated in the German speaking world, the opera house of Rijeka remembered Marinaio, not just because of the location Lesina where the action is set, but because of the grand ballet in act 2 which includes Croatian national dances, not to mention the cavatina “La Dalmatina.”

The harbor of Rijeka today. (Photo: Vladimir Soic / Unsplash)

During the bicentenary there was an open-air performance of the piece in Rijeka which was broadcast on TV. This broadcast was streamed on YouTube, it’s also the basis for this CD edition. (Prior to this there was a YouTube video of the 2013 performance in Split under Loris Voltilini, is has been taken down from YouTube again.)

It’s not known who created the Italian version of Anton Langer’s German libretto. But even the Italian version of Langer’s piece doesn’t make for a “Romantic opera,” which is the genre description Suppé chose. The libretto had been slumbering for years in a drawer in the composer’s writing desk, he seems to have only deemed it “worthy” of looking at again after Langer’s death.

Anton Langer in 1872, as drawn by Karl Klietsch. (Photo: From the magazine “Der Floh”)

Anton Langer (1824-1879) was part of a group of poets who were “world famous” in Vienna, and nowhere else. He wrote various pieces for Viennese theaters, all of them had one single goal: to entertain the emancipated bourgeoisie in the quickly expanding city. Langer was actually more talented, and important, as the editor of a satirical magazine. As an opera librettist he wasn’t such a big shot. Which Suppé must have realized, considering that he kept the libretto locked away for so long.

Sentimenal Sacrifice for the Love of the Young Ones

So what is the opera all about? It tells the story of a sailor/marine called Pietro who debarks the warship “Delfino” after 20 years. He had signed up for military service voluntarily when his fiancé Jela had been “robbed” by a rake. In the meantime Jela has died. But through her favorite song he recognizes her daughter, also called Jela. The town’s mayor or podestà Quirino wants to marry her, but she loves Nicolò. To get his competition out of the way Quirino wants to sign Nicolò up for military service on the recently returned warship. Pietro decides to sacrifice himself for the love of the young boy – and returns to the ship himself as a substitute for Nicolò.

A young man returning to harbor on his boat. (Photo: Oliver Sjostrom / Unsplash)

Suppé was only inspired by the plot to write some grandly lyrical numbers. A dramatic fire, however, is nowhere to be heard. You can tell that Suppé tried to not write in his successful “operetta” style, instead opting for a more serious or academic “opera” tone. Which only works partially.

Obviously there is some great music; anything else would be strange for a maestro of Suppé’s caliber who knew his craft backwards and forwards. The formal structure of the big ensembles – especially the finale of act 2 – is masterful, as are various soaring solos.

Strangely, the buffo arias seem uninspired. And it’s almost disturbing to hear the blatant copying of elements made famous by other composers: the marches sound like they’re by a young Giuseppe Verdi, the podestà’s solos are closely related to van Bett’s arias from Zar und Zimmermann by Albert Lortzing (who was briefly Suppé’s colleague as conductor at Theater an der Wien), then there’s the ending of the first act which makes you think of Caramello’s off-stage barcarole immediately without ever being as catchy as the Strauss original.

The opera itself is short: both acts combined are not much longer than 90 minutes, which is why at the world premiere the third act of Trovatore was included, with Verdi’s extra ballet music!

Overlooking present-day Rijeka. (Photo: Filip Boatic / Unsplash)

Conductor Adriano Martinolli d’Arcy and the orchestra of the opera house in Rijeka (formerly Fiume) sound somewhat labored and heavy handed on CD. The ensembles don’t shine and are too “thick.” The best moment on record is the entr’acte of act 2 and the ballet.

The agile soprano of Marjukka Tepponen as Jela and the internationally renowned baritone Ljubomir Puškariḉ give a lot of listening pleasure. Giorgio Surian as Quirino contributes his beautiful bass voice, but not much more. His character doesn’t come to life, which is not just Suppé’s fault.

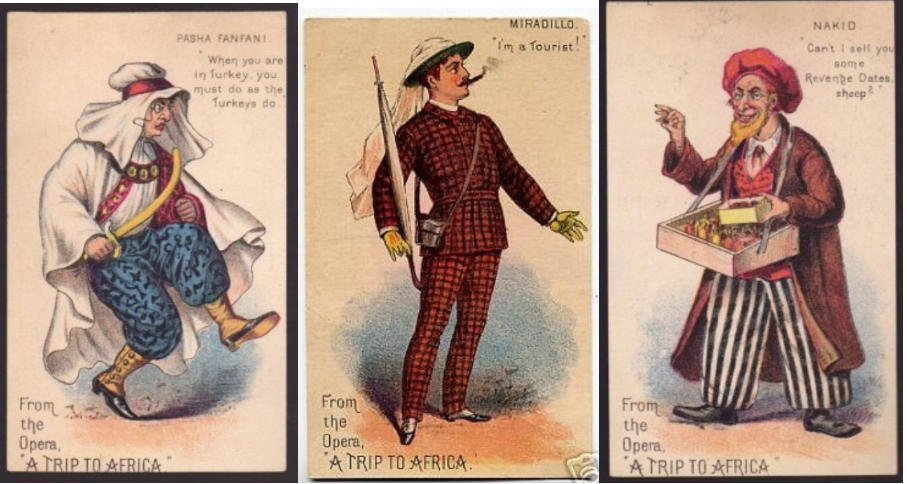

As I said, as Suppè’s biographer I am very thankful that cpo has made this late work available on CD. But I also find it astonishing that the company hasn’t focused on the big and once immensely successful works first. What a joy it would be to have Teufel auf Erden (1878), Donna Juanita (1880), Gascogner (1881) or even the recently revived Afrikareise (1883) in representative German language recordings. (To read more about the recent English language recording of A Trip to Africa conducted by Dario Salvi, click here.)

Suppé’s “Afrikareise” as seen in Boston, USA. (Photo: Dario Salvi Archive)

Not to mention a reference recording of Boccaccio (1879) in the original version with a mezzo soprano in the cross-dressed title role. A production at Volksoper Wien, conducted by Marc Piollet with real flair back in 2003 and with Antigone Papoulkas as the revolutionary poet, was broadcast by ORF. This recording would surely be more worthwhile to have than this sentimental sailor’s tale from Croatia (even if Helmuth Lohner’s staging looks as out of date now as it did in 2003.)

But then again, cpo’s release politics have been a mystery for so long, especially with regard to operetta, that I shouldn’t wonder too much. And just accept that the obvious is not so obvious for cpo.

To read the original German article on operalounge.de, click here.