Judith Wiemers

Operetta Research Center

21 October, 2017

Last weekend, the Royal Musical Association devoted one of its study days to what has controversially been described as the “silver age” of operetta. With its rather enticing title Gaiety, Glitz and Glamour, the conference attracted a smallish group of early-career researchers, PhD candidates, industry professionals and established academics, all sharing a sometimes guiltily tended passion for operetta in a discipline which traditionally regards operetta studies with a at least some recess suspicion. Initiator of the study day was Leeds-based musicology professor Derek Scott, who in recent years has spearheaded British operetta research with his generously funded European Research Council project on “German Operetta in London and New York 1907 – 1939”.

Lily Elsie and Joseph Coyne in ‘The Merry Widow’, 1907. Elsie and Coyne are playing the parts of ‘Sonia’ and ‘Prince Danilo’ respectively.

The themes of transculturality and cosmopolitan networks, both major focuses in Scott’s research, also permeated the presentations and panel discussion of the day. It also came as no surprise that the inaugurator of 20th century operetta and its unparalleled, dazzling rise to international success, featured: Lehár’s The Merry Widow (1905). First up was head of publications at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Jon Snelson. In his talk, Jon related the dawn of British operetta in the early decades of the 20th century to the Merry Widow craze set off after its London premiere in 1907. Léhar’s work launched what Jon terms a “romantic renaissance”, with Viennese-style operetta complementing or replacing the high-paced musical farces of a mostly American provenance popular in the West End.

LP cover of “The Dancing Years” by Ivor Novello. (Photo: Judith Wiemers)

By the end of the 1920s however, continental operetta had become chronologically removed from its audience. It continued to exist as a picturesque spectacle of nostalgic escapism, until Noel Coward’s Bitter Sweet (1929) became the prototype of British operetta. Thanks to Coward’s pioneering work, Jon suggests, composing operetta was no longer seen as “treading on foreign ground”. Ten years later, Ivor Novello wrote another Vienna-themed operetta, however with a dramatically different approach than his predecessors. Stripped of unnecessary spectacle, The Dancing Years (1939) was conceived as an astute comment on contemporary politics in Nazi Germany and Austria. In its first act however, it recreates a pre-war Vienna of 1911, stripped of West End nostalgia but evoking “Edwardian pre-war security”. As Jon argues, the operetta composed by character Rudi Kleber, Lorelai, was both conceptually and musically modelled on the Merry Widow. Interestingly, many scenes with Nazi references were cut from this operetta for performances after the Second World War.

Sheet music cover for Lehár’s “La Vedova Allegra,” i.a. “The Merry Widow” in Italian. (Photo: Judith Wiemers)

The next presentation by Valeria de Lucca explored the The Merry Widow and its reception in Italy (where it became La Vedova allegra. As early as 1906, the La Scala orchestra recorded the work, and in April 1907 – before the premières in London or New York – opened in Milano. As in other cities, public demand was insatiable, but as Valerie intimates, Italian critics were not going to willingly accept a genre as frivolous as operetta to compete with what they regarded as the sacrosanct pinnacle of musical art; opera. In the years to follow, the discrepancies between critical responses to Viennese operetta as lavish and shallow and the audience’s appetite for light-hearted romantic fare remained strong.

The critics’ disdain of the genre and its affiliations with Germany and Austria hardened considerably during the First World War. One critic wrote, “It is strange to observe that the Italians are fearless in the fire of the Austrian bombardments and yet give way lazily to the allure of a Lehár waltz.” The demand for original Italian operetta even prompted Italian composers to falsely put their names to Viennese operettas, as Valeria has found out. There were new works as well however, most of which are still to be discovered. One piece was a direct response to The Merry Widow. Called Danilo, it follows the story of the count after Hanna/Sonia has died, and – in very basic terms – replicates the Merry Widow plot replacing the French beauty with a Venetian. As Valeria assures us, the libretto is rather unimaginative, but she is hopeful to find more promising original Italian operetta in the future.

Film still “The Man on the Flying Trapeze.” (Photo: Judith Wiemers)

Third on the podium was Katie Gardner, PhD student at Oxford, who presented on the transnational cultural imagination of the circus performer. In her talk, Katie argues that the mythology surrounding the circus performer has, to an extent, been generated by the circus itself. As a first example, she explores the phenomenon of the trapeze man, who in his traditional representation combines both male and female traits. Skilled, muscular, agile and strong, the “flying man” on the trapeze is usually fashioned as a seducer. Despite his highly athletic appearance, he is also conceived to have a romantic, feminine streak and inexhaustible charm. Katie uses several video examples to demonstrate her findings. In the first, Popeye and the Man on the Flying Trapeze (1934), the circus performer has stolen Popeyes’ love interest, whom he can only physically “retrieve” by gobbling down some energising spinach.

The trapeze man in this cartoon, complete with moustache, was based on Jules Leotard – the iconic trapeze acrobat and inventor of a piece of fashion no less iconic. As Katie explains, circus performers were not only retrospectively mythologised. During their performances, female acrobats such as Lilian Leitzel openly played with stereotypes of femininity, pretending to faint, only to make the acrobatic stunts to follow all the more impressive. The American aerialist and female impersonator “Barbette” also toyed with gender clichés when stunning his audience with break-neck trapeze routines performed in full drag in the 1920s and 1930s. Barbette, who caused a stir both in American and Europe, (did he inspire Tucholsky’s Seifenblasen [1931] Schünzel’s Viktor und Viktoria [1933] and its British adaptation First a Girl [1935]?) only revealed himself as male at the very end of his act for heightened effect. Towards the end of her talk, Katie related the image of the circus performer to Kálmán’s Zirkusprinzessin (1926) and the mysterious character of Mister X, whose skill as a circus rider is an indispensable part of his allure.

The curtain for the original Viennese “Zirkusprinzessin” production 1926.

After a lunch break, the delegates reassembled for an interview with Dr Tobias Becker on his published doctoral dissertation Inszenierte Moderne – Populäres Theater in Berlin und London, 1880 – 1930 (2014), which Derek Scott introduces as a monograph set to become a standard work. Becker’s book is devoted to the cultural exchange between the popular theatre realms of Berlin and London, focussing on theatrical spaces, relationships between popular theatre and politics, as well as economic aspects of operetta. Becker, who also co-edited the excellent compendium Popular Musical Theatre in London and Berlin 1890 – 1939 (2014, with a contribution by Derek Scott also), commented on similarities of censorship regulations in Berlin and London.

The German capital Berlin, Unter den Linden, at the end of the 19th century.

In Berlin’s theatrical centre of the late 19th and early 29th century, Friedrichstraße, police staff occasionally went to theatre performances with the script to make sure that performers didn’t diverge from the officially approved version of any piece. Particularly interesting were Becker’s comments on class differences in London and Berlin theatres respectively. While in London theatres, audiences from all social classes shared the same space, separated only by seating areas in the auditorium, social stratification was more extreme in Berlin. Here, certain theatres, such as the Metropol (today’s Komische Oper), were inaccessible to lower social classes, which could not have afforded even the cheaper tickets on offer.

Judith Wiemers getting ready to present her talk on Abraham. (Photo: Judith Wiemers)

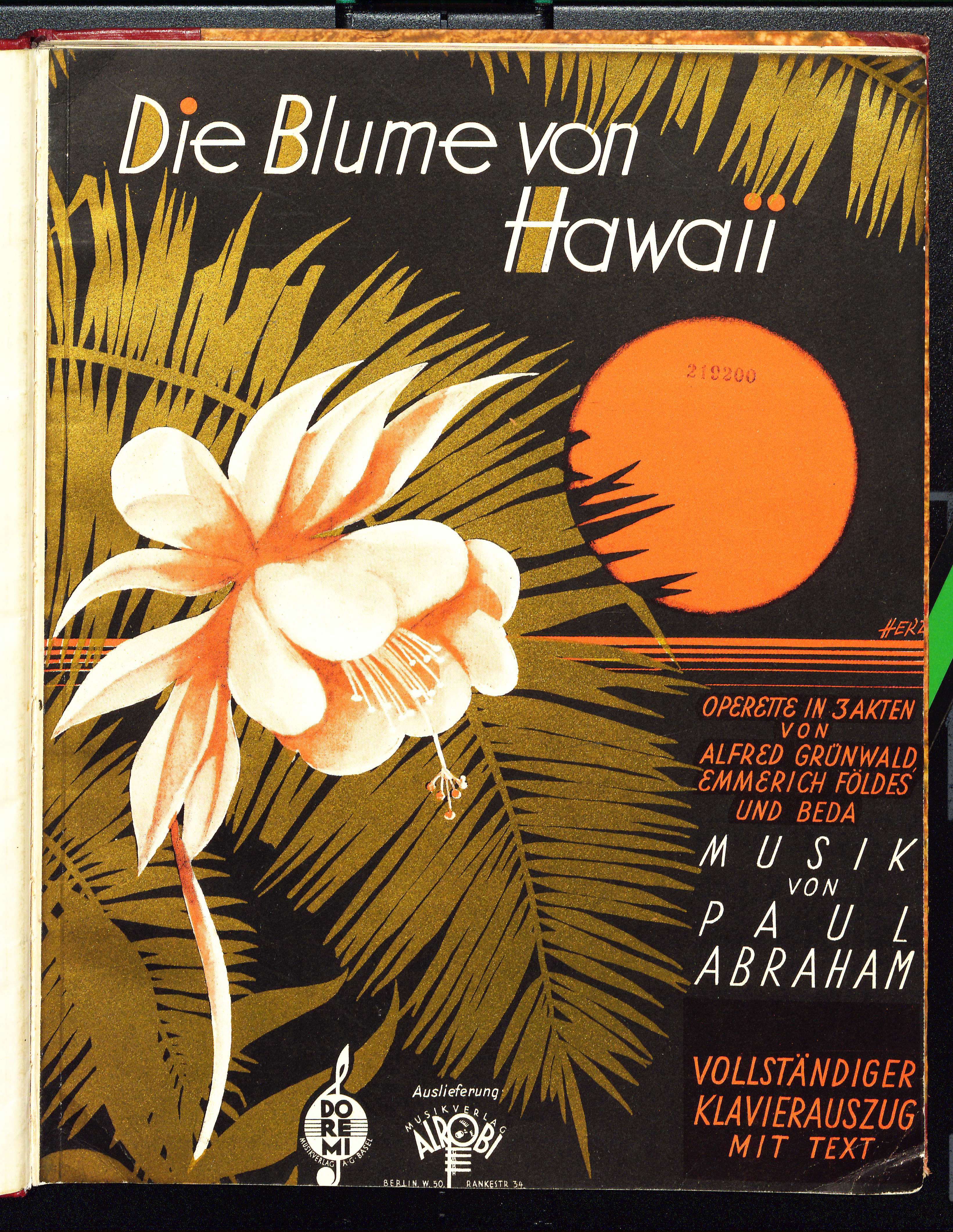

After Tobias, I presented on the American motifs in Paul Abraham’s 1930s operettas. I am a PhD student at Queen’s University currently finishing my PhD on German film musicals 1929 – 1945. My presentation addressed the various ways in which the operettas by Abraham and his two librettists Fritz Löhner-Beda and Alfred Grünwald related to popular American culture of the decade through text, music, and choreography. The talk explored the librettists’ joyful adaptation of common American and English expressions in works such as Viktoria und ihr Husar (1930) and Die Blume von Hawaii (1931), as well as reflections on German reception of American culture through Abraham’s songs, for example in Ball im Savoy (1932) and Märchen im Grand Hotel (1934). Songs such as “Känguruh Fox” and “Black Walk” used fictional dance terms to comment on the influx of fashionable American and British dances of the 1920s and 1930s.

The talk also revealed concrete musical influences of popular American songwriters Cole Porter and George Gershwin, which Abraham emulated, or indeed copied in his operetta songs. In a second step, the presentation highlighted how film adaptations complemented the topicality of Abraham’s operettas with cinematographic devices popular at their time. An example was the emulation of Busby Berkeley’s top shot aesthetic used in Ball im Savoy. The success of Abraham’s Viktoria and her Hussar and Ball at the Savoy in the West End were also discussed briefly.

Ball room scene from Charell’s “Der Kongress tanzt.” (Photo: Judith Wiemers)

Last but not least was Stefanie Arend’s presentation on Erik Charell’s “operetta extravaganza” film Der Kongress tanzt (The Congress dances, 1931). Stefanie, who is a PhD student at Oxford University, describes the film as the prototype of the genre of film operetta, which adopted some of Viennese operetta’s themes, and certainly its splurge on lavish costumes and grand settings. Despite being allocated a generous budget by Ufa’s right-wing managing director Hugenberg, producer Pommer and director Charell continued to overspend, to Hugenberg’s dismay. In the end however, the huge success of Der Kongress tanzt in Germany, France, Britain and beyond rendered the expense of several million Reichsmark a good investment.

Stephanie draws several convincing links between operetta traditions and the film, such as the three-act structure, the theme of 19th-century Vienna, “paper-cut” characters, and composer Werner Richard Heymann’s musical citations of Josef Strauss melodies. Stefanie argues that the pioneering role of Der Kongress tanzt was strongly predicated on its integration into a larger network of media. Never before had music publishers, recording companies, advertising agencies and the film industry been as entangled, and dependent on each to a comparable extent.

Sheet music cover “Die Blume von Hawaii.”

What is there to be taken away from the study day in terms of broader trends in British operetta studies and its place in academic musicology? Generally speaking, all presentations addressed operetta as a popular genre deeply entrenched in the time of its production, influenced by and reflective of social, cultural and political backgrounds. Another theme permeating the day was that of operetta as an internationally successful commercial product affected by the economic trends of its hotspots European and American urban centres.

As Derek pointed out, national narratives in the academic discourse of popular theatre seem to recede in favour of those exploring the transnational and transatlantic relationships between cities. Within British musicology, operetta studies is still very much a neglected field often scoffed at by “serious” musicologists. However, it is extremely heartening that somebody as firmly associated with conventional opera production and research as Jon Snelson publically “outs” himself as an operetta lover.

Hopefully Derek Scott’s ambitious research will also encourage even more young researchers to discover the endless riches of operetta and delve not only in the dissemination of German/Austrian operetta but also investigate similar trajectories of British operetta in the vein of Coward and Novello.

An interesting article- would love to have been at this lecture series.

G