Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

28 March, 2016

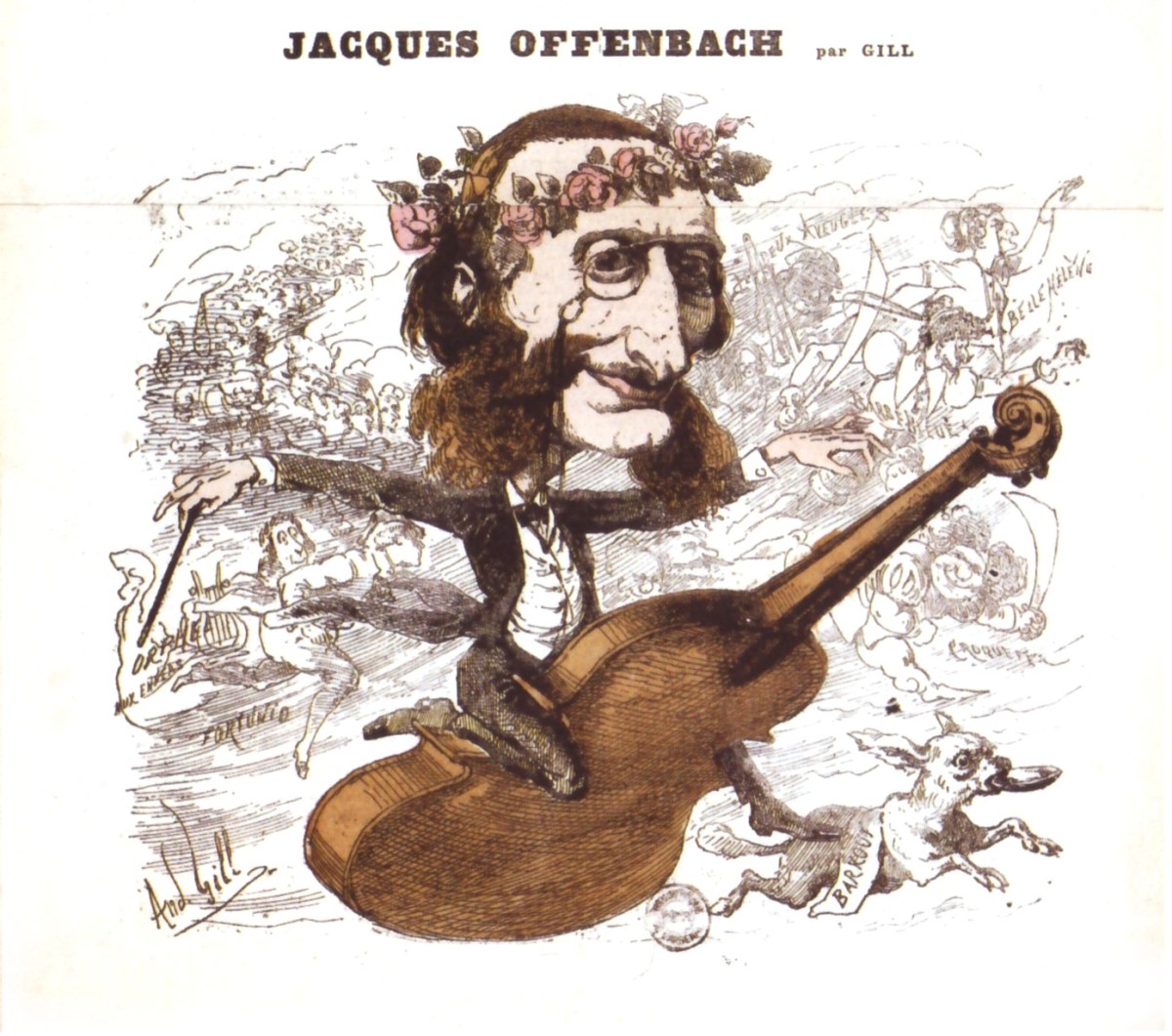

The genre operetta was invented around 1850 in Paris, as a new and independent musical theater form in the modern sense of the word. Its founding fathers were Florimond Ronger, aka Hervé, and Jacques Offenbach. The works they created are characterized by extreme anti-realism and grotesque exaggeration: they presented a Monty Pythonesque kind of parody of the societal situation and of the then current classical music scene.

Jacques Offenbach riding his success, a caricature from a Paris newspaper.

As a result, these early slapstick operettas contained recycled music that never strives for “truthfulness” like 19th century opera often did: instead it permanently deconstructed itself, which makes these scores very avant-garde from today’s point of view. The works of Hervé and Offenbach were also performed in theaters frequented by a demi-monde audience, consisting of high class male spectators and their female companions on the stage, behind the stage, and in the auditorium.

In his book Jacques Offenbach and the Paris of His Time Siegfried Kracauer writes: “The circle of bon vivants associated with the great courtesans numbered nearly one hundred fashionable gentlemen. They all came from an aristocratic background and commanded absolute authority in questions of sophisticated behavior. Their frivolity expressed itself in the contempt they had for the Bourgeoisie. They expressed this contempt by living a life that consciously transgressed middle-class conventions.”[1] Emile Zola offers a literary treatment of this operetta situation in his novel Nana, which tells the fictionally enhanced story of Offenbach star courtesan Hortense Schneider, who takes Paris by storm as a nude “blonde Venus” of unheard of lascivity: “Nana’s sexuality drove the men in the audience crazy. And it opened up unknown depths of desire in them. She only smiled at this […] with the smile of a man-eating woman.”[2]

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, as seen in the “Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen,” 1899.

The demi-monde atmosphere of the theater, which functioned as a kind of brothel, and the desire of the high-class audience to distinguish itself from conventional morality, allowed the creators of the original operettas in Paris to present very non-normative behavior on their stages. It also allowed them a very liberal treatment of then current moral standards, which Offenbach’s audience wished to ridicule. In this liberated atmosphere, the idea of a same-sex marriage was first presented – as an absurd joke – in Offenbach’s 1868 L’île de Tulipatan. It is the same year in which Karl Maria Kertbeny first used the word homosexuality as an antonym for heterosexuality and monosexuality. And it is only one year after Karl Heinrich Ulrichs had the world’s first official coming-out in 1867 at the German lawyer’s meeting in Munich, in front of 500 colleagues. He wanted to present the idea of legally accepting marriage for “Urninge” (gay people). He did not get to that point because he was booed off the podium. Still, that day marks the beginning of the modern gay rights movement. And the writers of operetta – with their keen sense for the topical – picked this up immediately.

Sheet music for a quadrille from Offenbach’s “L’île de Tulipatan.”

Many other now highly current topics such as gender and gender mainstreaming where also constantly debated in these original operettas that played, again and again, with cross-dressing, with women in men’s roles, and men in women’s roles. This was considered shocking at the time, and many critics labeled such gender confusion on the operetta stage “horrible prettiness” as well as “satanic subversiveness”.[3] This branded the new genre, exported all over the world and labeled “operetta” in German speaking countries, as scandalous. It only made the shows by Hervé and Offenbach more popular and commercially successful, in Vienna, Berlin, London, New York, Australia, New Zeeland, and South America.

When Offenbach’s medieval chastity farce Genevieve de Brabant arrived in New York in 1868 the reviewer of the Tribune called it “the most revolting mass of filth that has ever been shown on the boards of a respectable place of amusement in this city“. He continued: “Geneviève is not merely indecent, […] it grovels in a low depth, even below decency.” This corresponds with an evaluation from Meyers Konversations-Lexikon from 1877. In its Offenbach entry is claims: “Most of his operettas […] are so infected by the spirit of the demi-monde, that their obscene topics and sensual, often trivial music has a decidedly demoralizing effect on the larger theater going public.”

Charicature of Offenbach’s theater, the Bouffess Parisienes.

This demoralizing effect drew in hoards of male viewers, and as a consequence females too. They, in turn, wanted to see attractive men on the stage. Which is exactly what they got, as Offenbach’s British star singer Emily Soldene describes in her autobiography My Theatrical and Musical Recollections (1896).

The financial success of the new genre, with its highly erotic female and male stars, inspired many imitators; in Vienna these were most notably Franz von Suppé and Johann Strauss Jr. who copied French originals. After the Prussian-French war of 1870/71, however, a counter movement started that wanted to present a respectable alternative for a less morally liberal mass audience.

NANCE CHARACTERS

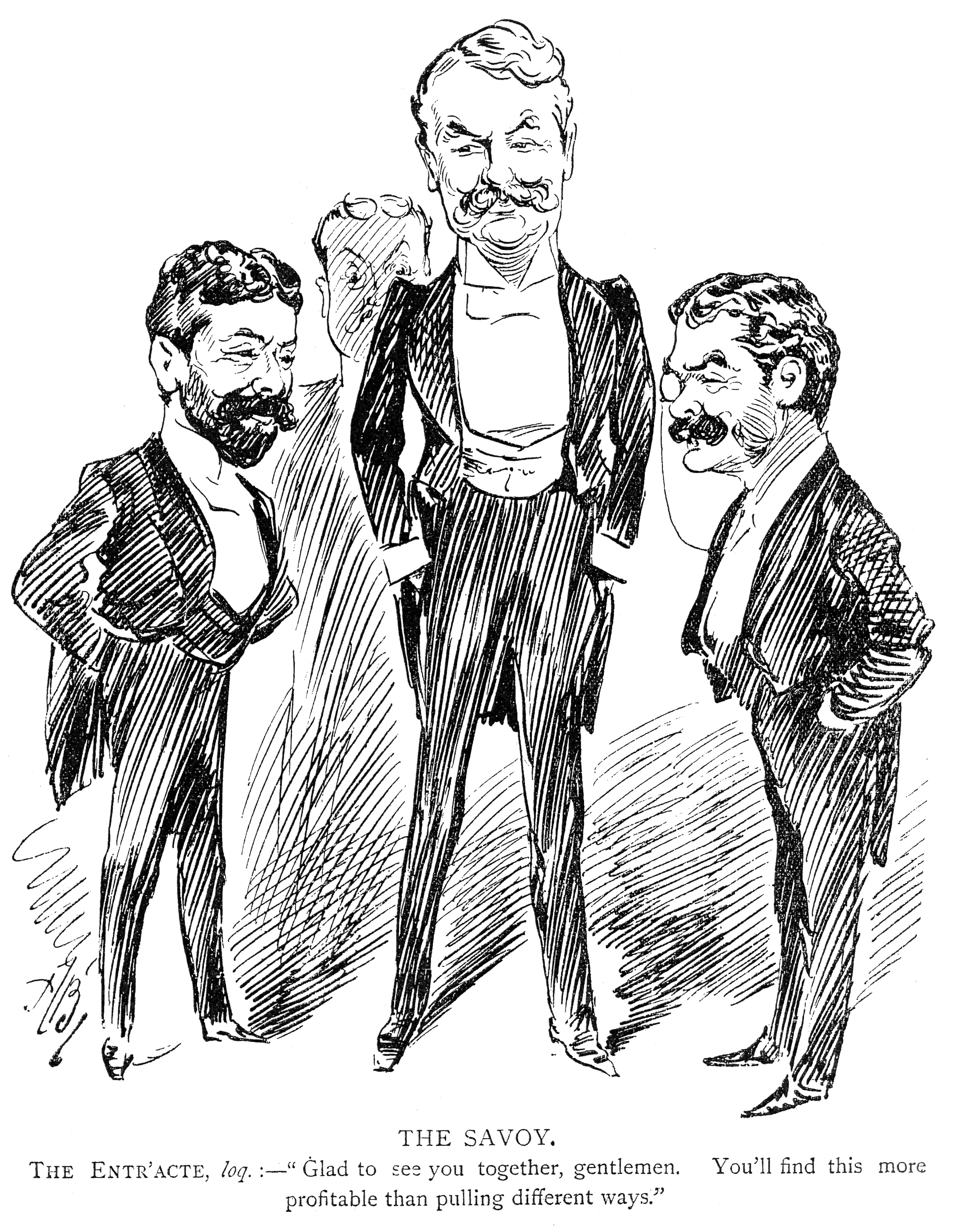

Impressario Richard D’Oyly Carte (l.) with Gilbert & Sullivan.

One of these morally more acceptable alternatives was, in Great Britain, the works of Gilbert & Sullivan. Together with impresario Richard D’Oyly Carte they created, from 1871 onwards, the so called Savoy Operas, a toned down version of Offenbach’s original model. The authors were expressly concerned about “bourgeois respectability“.[4] There was no nudity, no risqué elements, and no cross-dressing. In her Gilbert & Sullivan book Carolyn Williams writes in 2011: “Gilbert especially was scrupulous – even avuncular and fussy – about correct middle-class feminine behavior, insisting that the female members of the chorus not be thought coarse in any way. […] The women of the Savoy chorus were marketed as exceptionally beautiful, but chaste – to be looked at, but not to be approached.”[5]

Nonetheless, even in this family friendly version, the genre operetta had the reputation of the “forbidden” and “frivolous” that made it a bestselling item, with scandal and an overthrowing of moral standards being avoided only at the very last moment.

No operetta libretto of the 19th and early 20th century uses the word homosexual. Still, many shows present so called Nance characters that are especially feminine, affected, and camp. They suggest homosexuality through their way of moving, without explicitly labeling themselves as different. After all, homosexual acts were criminalized in most countries where operettas played until the late 1960s. This explains why any direct verbal discussion of homosexuality and homosexual behavior on the open stage was impossible, certainly while there were still censorship authorities operating in the background.

“The Nance,” Playbill of the 2013 play by Douglas Carter Beane, starring Nathan Lane.

While Nance characters are usually restricted to the comical supporting cast, and while the first open representation of a gay character in an “operetta” did not happen until 2006, with The Beastly Bombing: A Terrible Tale of Terrorists Tamed by the Tangles of True Love, there is a famous early example of a Nance character that can be interpreted as homosexual, at the center of an operetta: Gilbert & Sullivan‘s Reginald Bunthornein Patience from 1881.

Lady Jane and Bunthorne in a 1919 production of “Patience.”

This show is about the aestheticism movement in England and the super camp poet Bunthorne. He describes himself in a song as “A most intense young man, A soulful-eyed young man, An ultra-poetical, super-aesthetical, Out-of-the-way young man!” Later he adds, he is “a Francesca da Rimini, miminy, piminy, Je-ne-sais-quoi young man.” This “Je-ne-sais-quoi young man” is constantly pursued by 20 “love-sick maidens” who admire and desire him for his otherness; also, because he clearly breaks with social norms and traditional family models. This must be seen in direct contrast to the male ideal and family ideal of the military dragoons who consist of the ex fiancées of the lovesick ladies. While these modern women have no wish to conform to the dragoon’s antiquated expectations of males and females, Bunthorne has no interest in these women. He claims to love only one – unattainable – woman: the milkmaid Patience. This leads to some rather hilarious complications, in the course of which the dragoons try to pose as affected aesthetes with a parade of camp movements, to win back their fiancées. They sing: “You hold yourself like this [attitude], You hold yourself like that [attitude], By hook and crook you try to look both angular and flat [attitude]. We venture to expect That what we recollect, Though but a part of true High Art, will have its due effect.”[6]

The dragoons in “Patience” posing in the new fashion, to win back their girlfriends.

In the end, Gilbert and Sullivan bring together the various couples in an absurd mass wedding ceremony. The only one left behind, unmarried, is Bunthorne. There is no partner for him, the outsider and oddball. In the final rondo he sings: “In that case unprecedented, Single I must live and die – I shall have to be contented With a tulip or lily!”

Bunthorne as seen on a poster for a US production.

It is difficult to know how aware the 1881 audience was that this show could be read as a sketch for a new way of living unmarried with a tulip or lily, beyond hetero-normativity and without starting a family. That Patience was later so intensively associated with homosexuality in the modern sense of the word, is because Bunthorne was seen as an alter ego of Oscar Wilde whose homosexuality was common knowledge after the notorious 1895 trials.

Wilde was not the sole role model for Bunthorne, yet Richard D’Oyly Carte hired a young Wilde in 1882 to go on a North America tour and create interest in the aesthetic movement, which in turn was meant to stir interest in Patience. When entering the USA Wilde uttered one of his most famous lines to the custom authorities in New York: “I have nothing to declare but my genius.”

Oscar Wilde during his North America tour.

Yet, even before Wilde’s three court cases about lewd behavior, which made him the most famous homosexual in the world, various circles in Britain associated Wilde’s avatar Bunthorne with homoerotic actions. In the course of the Cleveland Street affair of 1889/90, when the police arrested telegram boys in a male brothel, the magazine Punch published a satirical alternative version of Bunthorne’s patter song, with acknowledgements to the author of Patience.“ The crude rhyme reads:

If you aim to be a Shocker, carnal theories to cocker is the best way to begin

And every one will say,

As you worm your wicked way,

“If that’s allowable to him which was criminal in me,

What a very emancipated kind of youth this kind of youth must be.”

At the very latest, after Wilde’s being sentenced to two years in prison with hard labor, everyone saw the parallels between Bunthorne and Wilde, and understood that this camp aesthete was a representative of a new race of men. Even though Bunthorne is a figure of ridicule in the operetta, threatening social structures with his behavior, and even though he remains isolated and without a partner in the show, he still is “an early moment in the long process of the homosexual emerging from the closet of representation,“ as Vincent Lankewish writes in his essay “No Patience for the Marriage Plot”.[7]

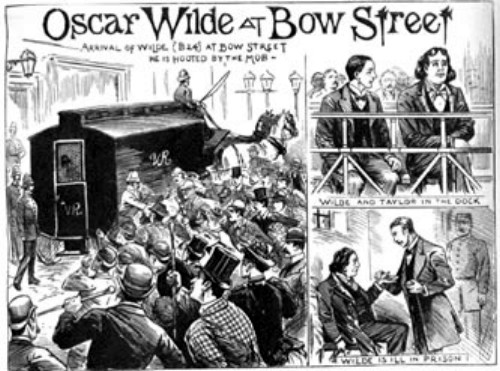

Oscar Wilde being taken to Bow Street magistrates court.

ZERO PATIENCE

As a ground breaking early example of a public representation of homosexuality in musical theater, Patience later played an important role in the Gay Liberation movement. In his 1993 AIDS film Zero Patience director John Greyson stresses the importance of the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta as the starting point of public visibility of homosexuals, which is juxtaposed with patient zero Gaëton Dugas as the other end of the historical time line, at the height of the health epidemic. In the film, the mysteriously undead Sir Richard Burton (translator of Tales of 1001 Nights, and the inventor of the theory of the sotadic zone) works for a museum of natural history, for which he is organizing a Hall of Contagion, presenting the major epidemics that have haunted humanity. In this hall, Dugas will be featured. He appears as an attractive ghost and begins an affair with Burton, finally bringing him to admit his long-suppressed homosexuality. In this film about acceptance of homosexual longing and the death of thousands of gay men, there is the evil company Gilbert Sullivan Pharmaceuticals which produces the AIDS medication AZT – making a fortune at the expense of homosexuals. This is a straightforward criticism of Gilbert & Sullivan, who joke at the expense of Bunthorne, only to achieve a box office success.

Still, their Patience remains an all-important point of departure, a new beginning, if you will. Carolyn Williams writes in Gilbert and Sullivan: Gender, Genre, Parody in a chapter on “Bunthorne in the History of Homosexuality”: “To be represented explicitly in popular culture means to be reductively typed, misrecognized, misunderstood, and marked out for possible punishment.” She continues: “Yet without visibility in representation – and in social life – there is no opportunity for recognition.”[8] Williams, with reference to Lankewish, claims Patience and Zero Patience are two opposing poles in the long search for representations of homosexuality, spanning from the late 19th century to the late 20th century.

The first open representation of homosexuals and homosexuality did not happen on the operetta stage, because of historical restrictions, until The Beastly Bombing by Julien Nitzberg (text) and Roger Neill (music) in 2006. It is a show that consciously uses the Gilbert and Sullivan Savoy Opera model, combining it with contemporary world political content, as did G&S, back in their day. Nitzberg says: “Too often when people write political theater it is all cyanide and unbearably dull, didactic or preachy. It even turns off people who agree with the author’s political views. This format of music allowed us to make political statements without seeming dull. Because operetta is a weirdly old style of music, it is comforting and allows me as the lyricist to write modern discomforting lyrics. Somehow when the two are mixed together, it is amazing. I think this is partially because our music was consciously written in a 19th Century style. Having white supremacists and Al Qaeda terrorists sing that style of music creates a comical disconnect. But if you are dealing with the ugly social issues of our time, why not serve them up as a delicious bonbon?“

While this late “Cyanide Wrapped in Chocolate” operetta presented the first out and proud gay characters in the genre, long after the genre stopped being actively used by authors on a regular commercial basis in the 1950s, various large scale Broadway musicals gave us central gay characters in musical entertainment: from La Cage aux Folles in 1983 to Fun Home 2015, the latter being an example of the portrayal of male and female homosexuals in one show. Add to this the arrival of Hedwig and the Angry Inch on Broadway in 2015: a show about a central transsexual character.

THE INVENTION OF LOVE

A few years after Zero Patience, playwright Tom Stoppard also used the topic of Patience and Oscar Wilde in his 1997 play The Invention of Love. It juxtaposes the historical personalities of A. E. Housman and Wilde. Houseman refuses to out himself as homosexual, considering the word “barbaric”. At the same time, Wilde subscribes to this new way of living fully. Wilde sees himself as a representative of a turning point in history: “I lived at the turning point of the world when everything was waking up new – the New Drama, the New Novel, New Journalism, New Hedonism, New Paganism, and the New Woman.”

Cover for the print version of Stoppard’s “The Invention of Love.”

In act 2 of The Invention of Love, Housman and his secretly beloved Moses Jackson attend a performance of Patience in the newly erected and electrically illuminated Savoy Theatre in London. There, in the play, Bunthorne as a herald of new times and a new sexuality is seen on the stage, singing his already mentioned patter song (“If you’re anxious for to shine in the high aesthetic line as a man of culture rare […] You must lie upon the daisies and discourse in novel phrases of your complicated state of mind. […] And every one will say, As you walk your mystic way, ‘If this young man expresses himself in terms too deep for me, Why, what a very singularly deep young man this deep young man must be!”).[9]

After the performance, Housman and Jackson start a discussion. Jackson sees the new electric light at the Savoy as an example that there finally is a new light shining on a modern life, announcing a new era: “Electricity is going to change everything. Everything!“ According to Stoppard, it is the special invention of love by Wilde, this new way of loving and living in same-sex partnerships, that will define this new era and change everything. While Houseman fears the new light and these new times, Oscar Wilde and his avatar Bunthorne storm forward. In the play, Wilde says, looking back at his life: “Better a fallen rocket than never a burst of light. The blaze of my immolation threw its light into every corner of the land where uncounted young men sat each in his own darkness.”

Oscar Wilde and his lover, Lord Alfred.

Stoppard shows, in his play, how the historic Oscar Wilde emerges from the character of Reginald Bunthorne. Both stand for a new form of sexuality in the limelight of publicity. Both are the starting point of a new social order. In Stoppard’s play someone says: “We aren’t anything till there’s a word for it.” The character of Bunthorne, argues Dennis Denisoff, opens up the possibility for “the formation of new identities defined by unconventional sexualities.”

PEOPLE WHO LOVE LIKE US

The gay neo Nazi in “The Beastly Bombing,” LA production 2006. (Photo: Kim Gottlieb Walker)

While in 1881 the outsider Bunthorne was the effeminate laughing stock of the show, who cannot find a partner, the two central gay male characters in The Beastly Bombing are two brutal hyper-masculine terrorists: an Arab Al-Qaeda fighter and a North American White Supremacist with a shaved head. One cannot guess their sexual orientation from their outfits or way of moving. When they all fall into each other’s arms, in the sextet “People Who Love Like Us”, their friends have no problem at all with their sexual orientation. This shows how far the image of the gay man has developed in the meantime.

As Martin P. Levine puts it in his book Gay Macho: The Life and Death of the Homosexual Clone: “Liberation turned the ‘Boys in the Band’ into doped-up, sexed-out, Marlboro men.”[10] The Beastly Bombing plays with this new cliché, by having two additional terrorists portrayed in a feminine way, only to out them as heterosexual later in the show. This turns stereotypes upside down in multiple ways. Later the authors contrast all the men with a “gay” Jesus who sings a seductive waltz with the President of the USA, praising his “War on Terror” in a surreal homoerotic dream sequence. (By the way, composer Roger Neill also wrote the music to the Academy Award-winning film Beginners and the main title music, “Lisztomania,” for the Amazon Studios series Mozart in the Jungle.)

A scene from the original production of “The Beastly Bombing.” (Photo: Kim Gottlieb Walker)

In 2012, stage director Sasha Regan presented an all-male Patience in London, set in the Bloomsbury Circle of the 1920s, with new Charleston musical arrangements. In doing so, Regan finally turned the story into a homosexual tale where not only is Bunthorne gay, but everyone around him is too. Here, he is not an outsider anymore, but part of a social group. This, on the other hand, reduces the satirical potential of the show, as The Guardian noted: “[T]he essential Gilbertian joke is that these effete dandies prove far more sexually attractive than a bunch of butch dragoons do to 20 lovesick maidens – a subversive gag that gets slightly lost if the girls are played by pretty young men in print frocks who look as if they belong to the same club as the aesthetes. Even the hearty soldiers in this production give the impression they have pitched a good deal of camp in their time.”[11]

While the idea of a same-sex marriage was first presented in a French operetta in 1868 as a comic absurdity, marriage equality is a reality in many Western countries today, among them Offenbach’s France, Gilbert and Sullivan’s Great Britain, Oscar Wilde’s birthplace Ireland, and after a Supreme Court decision in the USA, too. Only Germany still subscribes to a discriminating Christian conservative societal model which the morally dangerous original operettas ridiculed. The fact that, of all things, the supposedly old-fashioned and dusty genre operetta was a forerunner and early advocate of sexual liberation and self-determination, proves that this underestimated and misjudged genre is more modern than it is given credit for today. Which makes it all the more worthwhile to remember its original subversiveness regarding gender and sexual norms. As the überbutch (cross-dressed) Hermosa sings in Tuliptatan, after her father has confessed “ce secret terrible” that her lover Prince Alexis is a woman, underneath the outward appearance of a man: “I’ll take her for my wife anyway!” she yodels, leaving her father standing in horror. She is not going to let a small detail like gender or dresses stop her from finding true happiness!

[1] Siegfried Kracauer, Jacques Offenbach und das Paris seiner Zeit, Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp 1994 [1. Ausgabe Amsterdam 1937], p.220-221. Translation Kevin Clarke.

[2] Émile Zola, Nana, Leipzig 1979, p. 38-39. Translation Kevin Clarke.

[3] Vgl. Robert C. Allen, Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque And American Culture, University of North Carolina Press 1991, p. 133.

[4] Vgl. Carolyn Williams, Gilbert and Sullivan: Gender, Genre, Parody, New York: Columbia University Press, 2011, p. 20.

[5] Williams, p. 21.

[6] Arthur S. Sullivan, The Complete Plays of Gilbert and Sullivan, New York/London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1976, p. 189

[7] Quoted from Williams, p. 169.

[8] Williams, p. 170.

[9] Arthur S. Sullivan, The Complete Plays of Gilbert and Sullivan, p. 169-169.

[10] Martin P. Levine, Gay Macho: The Life and Death of the Homosexual Clone, New York/London: New York University Press 1998, p. 7.

[11] Michael Billington, “Patience”, in: The Guardian, 20 February, 2012.