Alexandra Ivanoff, Budapest

Operetta Research Center

26 April, 2017

On Nagymezó, the historic theatre street of Budapest, a bronze statue of operetta composer Emmerich Kálmán sits on the end of a two-person bench, inviting passers-by to join him. Just in front of the statue, annexed to the opulent Budapest Operetta Theatre is the freshly restored and re-opened cabaret venue, now called Kálmán Imre Theater.

The inside of the new Kalman theater in Budapest, on opening night. (Photo: Budapesti Operettszínház)

On April 20, an opening ceremony took place inside the theatre in the afternoon to serve as both a public christening and a tickler for that evening’s program: the European premiere of Kálmán’s Riviera Girl, the Broadway adaptation of his successful Die Csardasfürstin. It was originally created by two of the American musical theatre world’s greatest writers: Guy Bolton and P.G. Wodehouse. Now, a Hungarian version of the English original was presented as an inauguration production by KERO, the Budapest Operetta Theater’s long-time artistic mastermind.

Sitting in the audience, flown in from Mexico, was Kálmán’s youngest daughter Yvonne, lending a lovely human link to the golden past. Also present was Michael Miller and his wife Nan. He is a prominent Los Angeles collector of operetta books and music who donated source materials to the production. He is also the head of the Operetta Foundation in LA that has released various – wonderful – US recordings of Kalman, Riviera Girl not among them, sofar.

Kalman’s daughter Yvonne and stage director KERO during the opening ceremony speeches at the new Imre Kálmán Theater. (Photo: Budapesti Operettszínház)

The Csárdásfürstin story was set in Vienna and Budapest during the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the plot dealt with serio-comic issues among characters from Bohemian society and nobility who, despite the era’s taboos on crossing class lines, still fell in love with each other. The plot for Riviera Girl needed to be tweaked due to the fact that the U.S. was at war with Austro-Hungary. (For a detailed account, click here.) Bolton/Wodehouse chose Monte Carlo as a more neutral setting in Europe that still offered plenty of show-biz razzmatazz, casinos (gambling is a major theme in this script), and a less socially conservative milieu for the mixing of such couples. The character changes also included two Americans who provided a new twist on the subplot. The only character with the same name as in Csárdásfürstin is the theatre singer Sylva, the title role. The 1917 show, which also introduced two new songs by Jerome Kern, enjoyed only a short run despite so many noteable names involved. But the production went on a very successful national tour for more than two years, recouping its investment. The show itself was revived in the USA only once, in 1932 in St. Louis, the extremely positive local reviews.

Sheet music cover for “Life’s a Tale” from Kálmán’s “The Riviera Girl.”

Budapest’s considerably updated reconstruction of Riviera Girl invited lively discussion about the virtues and the disadvantages (some might consider them unnecessary evils) of such updating. Suffice it to say that it, perhaps on purpose, stylistically reflects the entire century that it encompasses. Virtually ten decades’ worth of references to many dance styles, clothing styles, speech norms, musical arrangements, and societal behavior create a kind of time capsule kaleidoscope. All the while, though, the story line retains the same type of farcical scenarios typical of the early 20th century and, typical of Kálmán’s later works, blends together as much Americana as Hungariana.

Németh Attila and Kerényi Miklós Máté in the “Riviera Girl,” 2017. (Fotó: Gordon Eszter/Budapesti Operettszínház)

In addition to the csárdás, waltzes, and Hungarian foot-slapping folk styles, in Riviera Girl you’ll see and hear Dixieland jazz, swing, rap and hip-hop, disco, haunting Weill-esque accompaniments, tango, Broadway belting, Bob Fosse style choreography, military marches, retro and modern props, videos on the back wall, and a chorus of shirtless American gunslingers ready to shoot ‘em up.

Szabó P. Szilveszter in “The Riviera Girl.” (Photó: Gordon Eszter/Budapesti Operettszínház)

Csaba Horváth’s choreography runs the gamut and takes every risk one can take in a small space. Costumes (designed by Anni Füzér) range from demure frocks and tweed jackets to lots of black leather and sunglasses as well as lizard skin shoes and white suits.

Kardffy Aisha, Barkóczi Sándor, Lévai Enikő and György-Rózsa Sándor in “The Riviera Girl.” (Photó: Gordon Eszter/Budapesti Operettszínház)

And, in the inspired setting of Kern’s “A Bungalow in Quogue,” actors appear in oversized pig and chicken suits to reflect the humorous lyrics about leaving the city life and settling down on the farm.

Szendy Szilvi and Kerényi Miklós Máté with dancers, performing “A Bungalow in Quogue” from “Riviera Girl.” (Photó: Gordon Eszter/Budapesti Operettszínház)

It’s tempting to dismiss KERO’s redesign and Tamás Bolba’s modern orchestrations (there was no original score to be found in the Kálmán archive, unfortunately) that incorporated a few electronic sounds (including the Hammond organ) as disrepectful to the composer’s basic concept. But as anachronistic as much of it is, it actually works quite well. The various musical styles are always a complete surprise so one can never be bored by textural sameness, with the possible exception of the overuse of the key of C-major which predominates in many of the numbers. The updates also don’t detract from the drama’s intentions; we are kept on a taut tightrope of curiosity about what will happen next.

Németh Attila and Szabó P. Szilveszter in “Riviera Girl.” (Photó: Gordon Eszter/Budapesti Operettszínház)

Set decorator Tamás Rákay constructed a giant roulette wheel on a center aisle space immediately adjacent to center stage. This symbol of life’s gamble, chance, addiction, and good luck held sway in our eyes throughout the many romantic entanglements that played out before us and also served as alternate stage of sorts. But even though many of the scenarios involved modern behaviors, fashions, and singing styles (Sándor György-Rózsa’s bullet-proof and bronze-toned bari-tenor with killer high notes brought to mind the preferred lead male casting mold of current Broadway scores) we had the gorgeous melodies by Kálmán to keep our 21st century harmonically-starved brains happy.

Kerényi Miklós Máté in “The Riviera Girl.” (Photó: Gordon Eszter/Budapesti Operettszínház)

One of the more amusing moments was a satiric take on life in the casino/cabaret: a musical number that featured three strumpet-style chorines who sported a syncopated hand-clap routine punctuated by perfectly timed comic shrieks. And one of the memorably dramatic moments is the sudden long silence commanded by the aristocrat Michael, who breaks it with a quote from Nietsche: “The struggle for pleasure is the struggle for life.”

György-Rózsa Sándor and Lévai Enikő in “Riviera Girl.” (Photó: Gordon Eszter/Budapesti Operettszínház)

In the title role, Enikö Lévai lived up to the demands of her diva character, spinning out as many delicious high notes as gutteral grumbles in her frustrations with the men in her life. Those men included Sándor Barkóczi as Karl, the son of German aristocrat Michael, played by Szilveszter Szabó, and György-Rózsa as Victor, a Prince disguised as a casino worker; all three possessed extremely polished acting and singing chops. As the sprightly ingenue, Aisha Kardffy displayed considerable comic talent as Claire, the ditzy damsel trying to inveigle Karl to marry her instead of Sylva. As the American couple, Sam and Birdie Springer, Maté Miklós Kerényi and Szilvi Szendi excelled as the highly entertaining song & dance duo.

My only niggling issue with updating here — and this is primarily because the Kálmán Theatre is a small and delightfully intimate space — is why mike it to the hilt?

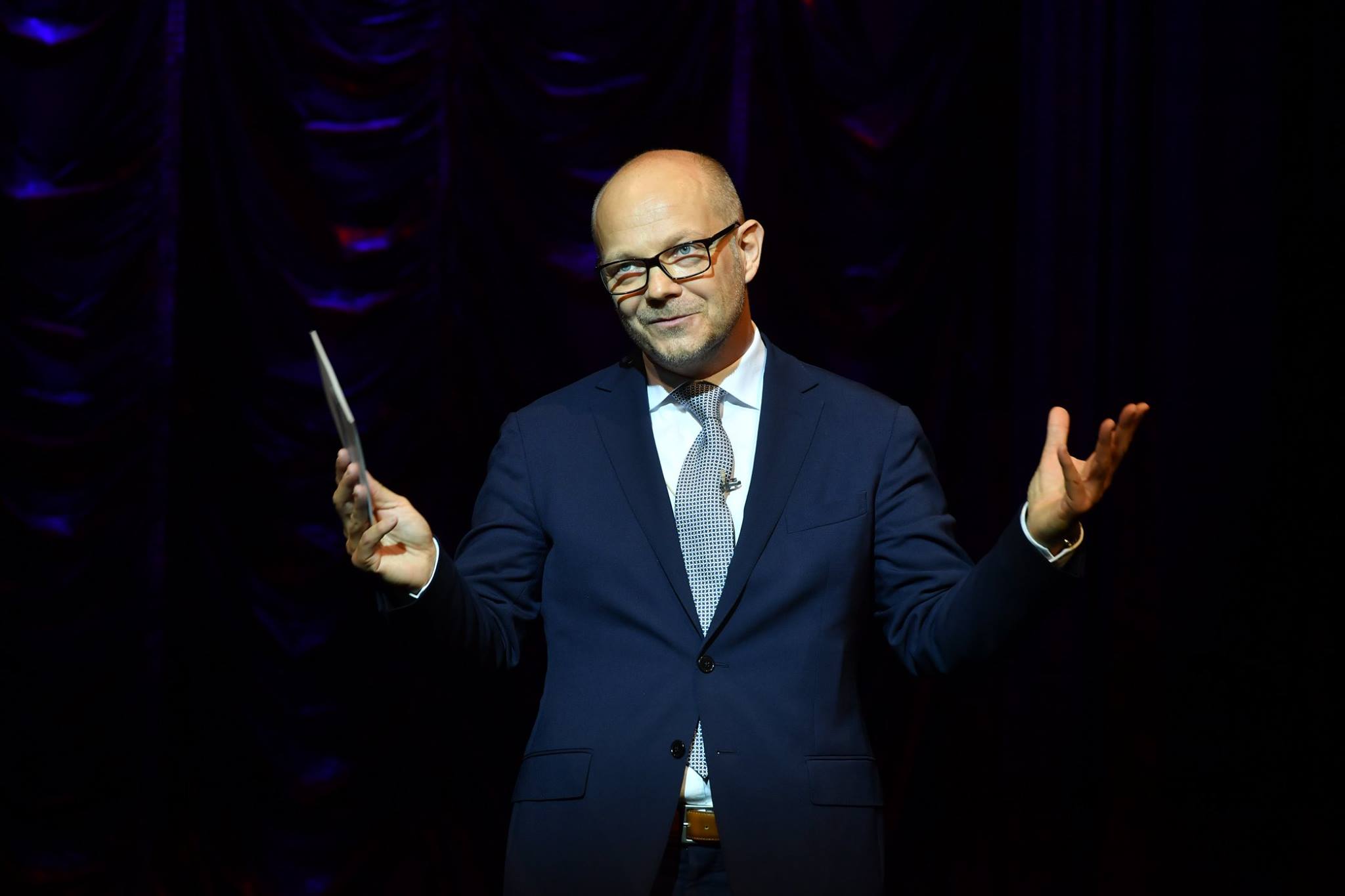

The director of the Budapest Operetta Theater, György Lőrinczy, welcoming the guests to the new Imre Kálmán Theatre. (Photó: Budapesti Operettszínház)

Better yet, why use miking at all? I’m sure the acoustics would favor any singing/speaking voice in that room. Overmiking, as was the case most of the time, steals the intimacy from us as well as distort the singer’s true sound, and doesn’t allow the performer to determine his or her own volume preferences from moment to moment. A little bit of discreet ambient miking, for both singers and orchestra, would give our poor pummeled ears a break and actually make us listen in a more attentive way.

[…] große Dinner an der intimen, verschnörkelten Zweitspielstätte des Operettenhauses, seit April Kálmán Theater genannt. Die Spitzenkräfte der ungarischen Operette von gestern wie heute unterbrachen die diversen […]