N.N.

Variety/Staunton Star-Times

24 September, 1917 and 2 June, 1932

Emmerich Kálmán’s Csardasfürstin opened on Broadway, at the New Amsterdam Theater, on 24 September 1917 under the new American title The Riviera Girl. Originally, “The Czardas Princess” was supposed to be called “The Monte Carlo Girl”. But the producers found the title had been generally used by burlesque shows, as The New York Times noted. Klaw & Erlanger gave it a lavish production at the same theatre, where The Merry Widow had been a triumph ten years earlier, in 1907. The showbusiness trade magazine Variety reviewed the production. ORCA associate Richard C. Norton dug up this and all the other relevant reviews from the libraries of New York City, so you can get a clearer picture of the US performance history of Die Csardasfürstin on its 100th birthday which the Budapest Operetta Theatre will celebrate with a conference on October 24/25, organised by Magdolna Jákfalvi and Attila Lőrinczy. Here’s the Variety review. (Thank you, Richard Norton!)

Newspaper ad for Kálmán’s “The Rviera Girl” on Broadway.

In making the production of The Rivera Girl, Klaw & Erlanger decided to turn to the modern school of stage decoration in the matter of both settings and costuming. Therefore, they engaged Josef Urban to design the scenes and the dresses. With this accomplished the producers evidently gave their undivided attention to the supervision of the building of the show and the sewing of the costumes and let the book “go hang.”

The result is that walking out of the New Amsterdam Theater after witnessing a performance of The Riviera Girl one carries away the recollection of a gorgeous scenic investure and an ever-occuring flood of colorful costumes, but that is all. There is nothing in the sore of the musical comedy by Emmerich Kalman that impresses and not a single strain of any melody that lingers in the brain or ear as one wanders forth, and as for the book and lyrics by Guy Bolton and P. G. Wodehouse, the less said the better. That is at least true of the book; the lyrics may be good, but when one doesn’t hear them one cannot judge. The best obtainable in a lyric way is an occasional word here and there, but that is all.

Morris Gest, P. G. Wodehouse, Guy Bolton, F. Ray Comstock and Jerome Kern taken circa 1917. (Photo: Wikipedia)

As for comedy in the book, there isn’t any, except for an out and out “hokum” fall and a very flagrant lift from the vaudeville act of Savoy & Brennan [one of whom is a famous cross-dresser, add.]. The latter is in very bad taste and reflects no credit on either the actor employing it, the author for sanctioning its use, or the management for permitting it. The “left” referred to is the use of the expression, “I’m glad you ast me, dearie, I’m glad you ast me,” which had it been employed but once in the first act and twice in the second act makes it all too apparent the “lift” was premeditated. Sam Hardy is the offender in this respect, and it is also he that is the perpetrator of the aforementioned “hokum” fall, which comes as the aftermath to the song, “Let’s Build a Little Bungalow in Quogue,” in the burlesque sailor’s hornpipe that hardy does. It brought the biggest laugh of the entire performance.

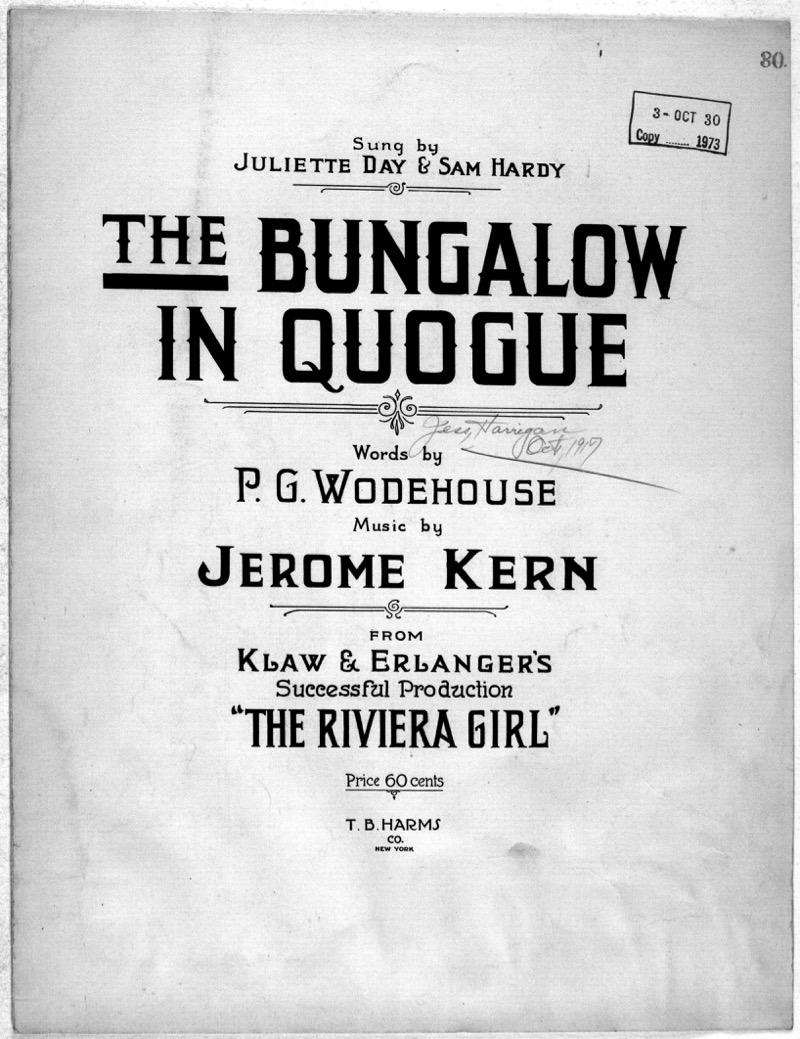

The added number by Jerome Kern, for the 1917 production of “The Riviera Girl.”

There are three acts, employing as many scenes, in which the action of The Riviera Girl, is revealed. The locale is Monte Carlo, and the first scene shows the Garden theater of the Cote d’Azur, splendidly done. The second is the garden surrounding the villa of one of the principals during the course of a flower fete, and the third is the rotunda of the Cote d’Azur at night. For all three Urban has employed that unusual blue sky for his back. It is the same blue that Maxfield Parrish is famed for, and further, there is a suggestion of the latter artists in the trees in the second act.

The story concerns a young nobleman who wishes to marry a vaudeville artiste, with the usual parental objections on the part of his father. The introduction of an extremely aggressive American from one of the towns of the hinterland, who is supposedly abroad to study gambling conditions for a report to a vice committee in America, but really trying to work out a system to break the bank, really starts the complications. It is his suggestion that the youth with the desire for matrimony be informed that his father can be tricked into accepting the girl. The scheme being to marry her to some broken-down nobleman, who will allow his name to be used for a fee, part the couple immediately after the ceremony until a divorce is arranged and then when she, freed by the court, with the title, the boy’s father can have no further objections. But the after is in on the deal and a double-cross has been arranged, the hired nobleman is to be further paid not to permit of a divorce until the boy has married elsewhere. As the story develops it is discovered the supposed waiter who was employed as the bridegroom is in reality a prince, and when the time for parting comes the bride discovers that she is really in love with him and he with her.

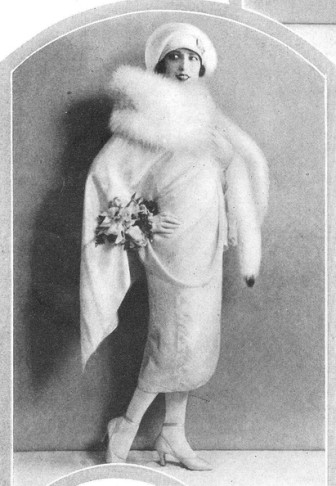

Wilda Bennett (1894-1967).

Wilda Bennett plays the title role in a charming but rather unanimated fashion, singing seven of the seventeen numbers in the show. Arthur Buckley has the tenor role of the youthful lover, Charles Lorenz, singing rather well, but handling his liens poorly. Carl Gantvoort as the Prince was all that could be desired from any standpoint, carrying his role most convincingly at all times. The comedy is entrusted to Sam Hardy, as the aggressive American, and J. Clarence Harvey as Baron Ferrier, and Louis Casavant as Count Michael Lorenz, the two later being boon companions. There are but two other principal women of note, Juliette Day as the wife of the American, and Viola Cain as the daughter of the baron. The former works hard and is extremely pleasing in all that she does. The work of the latter is hardly more than a bit.

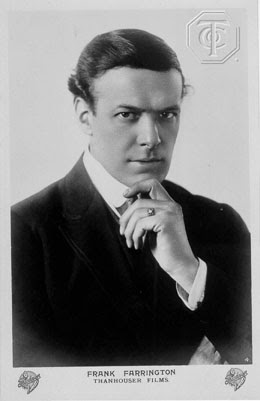

Frank Farrington started his career on Broadway in Kálman and Leo Fall operettas, before becoming a Hollywood silent movie star.

The other minor principals include first and foremost Frank Farrington as an English waiter who manages to extract laughs by trying to unburden his matrimonial troubles on everyone. Eugene Lockhart, proprietor of the Monte Carlo resort where two acts take place; William Sadler J. Lowe Murphy, Louise Evans and Marjorie Bentley, who has a dance specialty in each act.

There are six numbers in the first act, the one coming nearest to scoring being that led by Harvey and Casavant, backed by the male chorus, while Miss Bentley offers her first dance. In the second act there are, inclusive of the opening and final, seven numbers. A quartet, “Man, Man, Man,” might have been a hit had the lyrics been distinguishable by the audience, while duet by Hardy and Juliette Day, “Let’s Build a Little Bungalow in Quoque,” could have been developed into the hit of the show but for the same reason. It was not until the last act that one of the numbers really got over, and that was the comedy number, “Why Don’t They Hand It to Me?” led by Hardy with the chorus working well behind him. In this act there are but two numbers, but the opening chorus is a most elaborate affair.

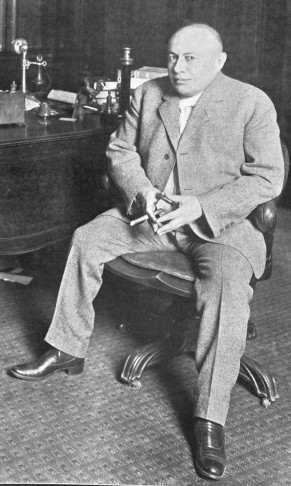

Abraham Lincoln Erlanger, from the production team Klaw & Erlanger. (Photo: Wikipedia)

There are thirty girls in the chorus and sixteen boys. In addition to this there are four dancers, Klaw & Erlanger duplicating the Gillingham idea of a quartet of super-chorus girls. In this case they are girls formerly with “The [Ziegfeld] Follies” namely Bessie Gros, Mae Garman, and Florence and Ethel Delamr. Some of the chorus boys double for bit here and there in the show.

All in all, The Riviera Girl is an entertainment that falls short of satisfying to a great extent, but the scenic and costuming are paramount. It is safe to predict though that Klaw & Erlanger will keep the show at the New Amsterdam for some little time, their advantage being that they get both ends, the house and the show. Of course, the practical guarantee of almost $80,000 that they have received from the ticket agencies will assure them their production cost, and after the first eight weeks of the run are completed, the show should turn a big profit. The agencies leave little more than a hundred seats on the lower floor for the house to dispose of and these, in conjunction with the upstairs business, will take care of the house end and leave something over to go toward the salaries. The show, however, is of the type that will be more of a downstairs draw rather than attracting balcony and gallery audiences.

The New Amsterdam Theatre on 42nd Street in New York, in 1905. (Photo: Wikipedia)

There is one feature of the performance that is worth more than passing mention and that is the unusually large orchestra, there being almost 40 men in the pit, and the manner in which they are handled by Charles Previn is as much a part of the performance as anything on stage.

After a long National Tour, The Riviera Girl was somewhat forgotten and overshadowed by the other later Kálmán hits on Broadway. However, in June 1932 there was a new production at the St. Louis Municipal Opera (an outdoor musical amphitheatre that seats 11,000 people) with Yvonne D’Arle in the title role. The Staunton Star-Times reviewed this production very positively, including the book by Bolton-Woodhouse that Variety had criticised. Here’s the 1932 review (for which we thank Michael Miller of the Operetta Archives in Los Angeles, who found it):

Municipal Opera enters the second week of its melody summer […] with Yvonne D’Arle in the title role, it presents one of Emmerich Kalman’s greatest Viennese operetta triumphs, The Riviera Girl. Miss D’Arle has been alike a star of the Metropolitan Opera House of New York and of Ziegfeld musical productions, returns to Municipal Opera to make her season’s debut in the fascinating role of a vaudeville singer for whose hand Guy Robertson and Leonard Ceeley, as two European noblemen, are suitors. There develops a jolly romance of intrigue, in the colorful course of which two Americans who have gone over to Monte Carlo to reform Europe discover a few things about life.

[…] The Kalman masterpiece is presented in a setting especially designed by Watson Barratt, one of the most distinguished masters of scenic décor in the contemporary American theatre, and art director for Municipal Opera this season. The musical setting is provided, of course, by a great symphonic orchestra of 50 and the unrivalled Municipal Opera chorus both under the direction of Giuseppe Bamboschek, for many years conductor at the Metropolitan Opera House and musical secretary to Director Gatti-Cazazza.

Yvonne D’Arle in 1926, when she appeared in a Ziegfeld production.

The Riviera Girl is gay, delightful fun from the outset. Count Michael Lorenz opposes the marriage of his son Charles to Sylvia Vareska, popular favorite among the singers at Monte Carlo. The infatuated Charles […] confides his father’s attitude to Count Ferrier […]. When Sam Springer, who with his wife, Birdie, has come to Monte Carlo to investigate gambling and institute a reform, overhears, he offers a solution to the young man’s problems. Syvlia, it seems, isn’t socially eligible to marry young Lorenz because she has no title. It is easy to get her one, says Sam. Just have her marry some count. As a countess she will be socially eligible, even if she is divorced. Sam knows that trick will work for he saw it done in a play back in Fishville, U.S.A.

Young Lorenz assents and persuades Sylvia. Ferrier seemingly is willing, but confides to Sam that he wants to see Lorenz marry his own daughter, Claire, for they were childhood sweethearts. Sam Springer can fix that, too. There is a great American institution called the double-cross, he says. Marry Sylvia to the no account count, and have him refuse to divorce her.

A view of Monte Carlo in 1914. (Photo: Wikipedia)

The intrigue develops as planned. Victor […] has lost his last sou at Monte Carlo, and agrees to act as a waiter in order that Anatole can spend his wedding night at home. Victor in his proper person, has been one of Sylvia Vareska’s greatest admirers. When Sam Springer can’t find a count willing to be married for the asking, the American asks Victor, and Victor assents.

There are jolly fun complications when it develops that Birdie Springer married Sam to reform him – and that Sam’s investigation of Monte Carlo was planned by him in order to try out the system he has schemed out with which to break the bank. There are romantic complications when Victor is exposed by Sam as being an imposter and a waiter.

As the days pass while Charles is waiting for the divorce which is to free the singer, he grows nearer to the flame of his childhood and when in the end Victor and Sylvia find happiness, a double wedding is in the offing.

So is the ship which is to take Sam Springer back to American after his wife, Birdie, has won at roulette what his system lost, and has decided Monte Carlo doesn’t need reforming.

Harry K. Morton as Sam Springer and Hope Emerson, the wife, as Birdie contribute most of the fun of an operetta, the lines of which sparkle with the wit and humor of Guy Bolton and P. G. Woodhouse, who are authors of the book. Kalman’s score contains such melody gems as “The Mountain Girl,” “The Fall of Man,” “There’ll Never be another Girl like Daisy,” “Life’sa Tale,” “Just a Voice to Call Me Dear,” “Half a Man,” “Will You Forget?” and “Gypsy Bring Your Fiddle” among others.

Louis Casavant my grandfather was in The Riviera Girl as Count Michael Lorenz and no mention is made of him.