Kurt Gänzl

Kurt of Gerolstein Blog

27 September, 2019

I first came seriously in contact with F. C. Burnand’s burlesque, Ixion, when working on my biography of burlesque megastar, Lydia Thompson. It was Lydia, of course, who made (her version) of the piece into a Transatlantic hit. But, before becoming famous in America and further afield, the piece had already been a huge London and provincial triumph in England. And it had had no Lydia Thompson at a top-billed star. The original production was very largely cast with young folk with no or little professional stage experience, a good few of them from amongst the wannabe ‘pupils’ of one aged actress. Of whom two put up the wherewithal … Enter: The Misses Pelham.

Ixion and Nephele, painted by Peter Paul Rubens in 1615.

Here’s a little piece I wrote about the two girls in question: Sophia Pelham (1837-1913) and Harriet Pelham (1840-1876).

The Misses Pelham hold a quaint little place in the history of theatre and music in England, which has earned them a mention in a number of books, the authors of which (myself included) really had and have no idea who they were. So I thought I had, finally, better find out.

The aristocratic names were, of course, too good to be true, echoing those of the seriously social Ladies Sophia and Harriet Pelham, but although the ‘Pelham’ was indeed fake, the Christian names were, actually, real. The Misses Pelham were the Misses Parker, daughters of one Benjamin Parker from Kettlesing Bottom, Yorks, and his wife Harriet Beckett née Bamford. And therein hangs a vast tale.

Harriet Parker was, if not exactly an heiress, the subject of various trusts and properties, as the youngest daughter of her mother, Mrs. John Bamford née Sophia Beckett, and the granddaughter of a certain John Beckett who counted his fortune in thousands. Benjamin, son of another Benjamin and his wife Sarah, of Hampsthwaite, was a plausible, good-looking fellow ‘of a gentlemanly appearance’, who turned out to be, at best, a rogue and, at worst, a villain. Harriet bore him three children (a son died, aged 12) and stuck with him, through more thin than thick, for more than 20 years.

The details of Benjamin’s misdeeds, and his countless appearances in every kind of British court, Criminal to Chancery, aren’t very exciting. Regular bankruptcies, sometimes tactical (the main ‘creditor’ was the widow Bamford, who seems to have harassed her trustees into lending him impossible sums), fraud, forgery of bills of exchange, conspiracy and the like, all under a variety of names. Like his name and his crime, his profession changed, each time he came up in court. So much so, that a judge was reduced to unkindly laughter. Wholesale tea dealer, wholesale grocer, a builder and architect in Hastings, dealer, contractor, starch manufacturer, merchant. When he filled in the 1841 census (shortly after a bankruptcy), from a three-servant home in Hampstead, he called himself ‘independent’, when the 1851 census came round, he was doing a turn in Queen’s prison, labeled ‘gentleman’.

So, Benjamin’s two daughters – ‘showy, good-hearted girls’, a contemporary described them – grew up in an atmosphere of disarray, moving from one home to another as the former address became too hot. But somewhere in all this strange life, Sophia and Harriet had music lessons, and they developed into pretty fair amateur vocalists. They first appear, to my eyes, on the platform as a pair, opening the program at one of Howard Glover’s mega concerts (3 January 1863), singing ‘I would that my love’ well enough to be brought back at the next (7 February) to give ‘The autumn song’ and no less than ‘Giorno d’orrore’. In March, they appeared at the Vocal Association, with Samuel Glover’s ‘I heard a voice’.

Then fate intervened, in the person of a certain Sarah Susannah Wilson née Prynne, previously Jarvis, otherwise ‘Mrs. Charles Selby’, a former burlesque and character actress grown, in her sixties and now an acting teacher. Mrs. Selby became ‘vastly interested’ in the two girls, took them up, and introduced them to the stage, on 18 May, at her Benefit. ‘The two sisters must go to school again for another season; the stage fright had such an effect on them that we were expecting them to break down every moment’, wrote a reviewer.

But, only a few months later, the recently widowed Mrs. Selby (d. 8 February 1873) announced that she had taken the Royalty Theatre for a season, and the Misses Pelham were to be in the company. The truth? They were in the company, because Mrs. Selby was nothing but a figurehead, paid 5 pounds a week and a split of the profits to be ‘directress’. The money was coming from somewhere in the Parker-Bamford-Beckett purse. Was it coincidence that Sophia Beckett Bamford had died weeks earlier?

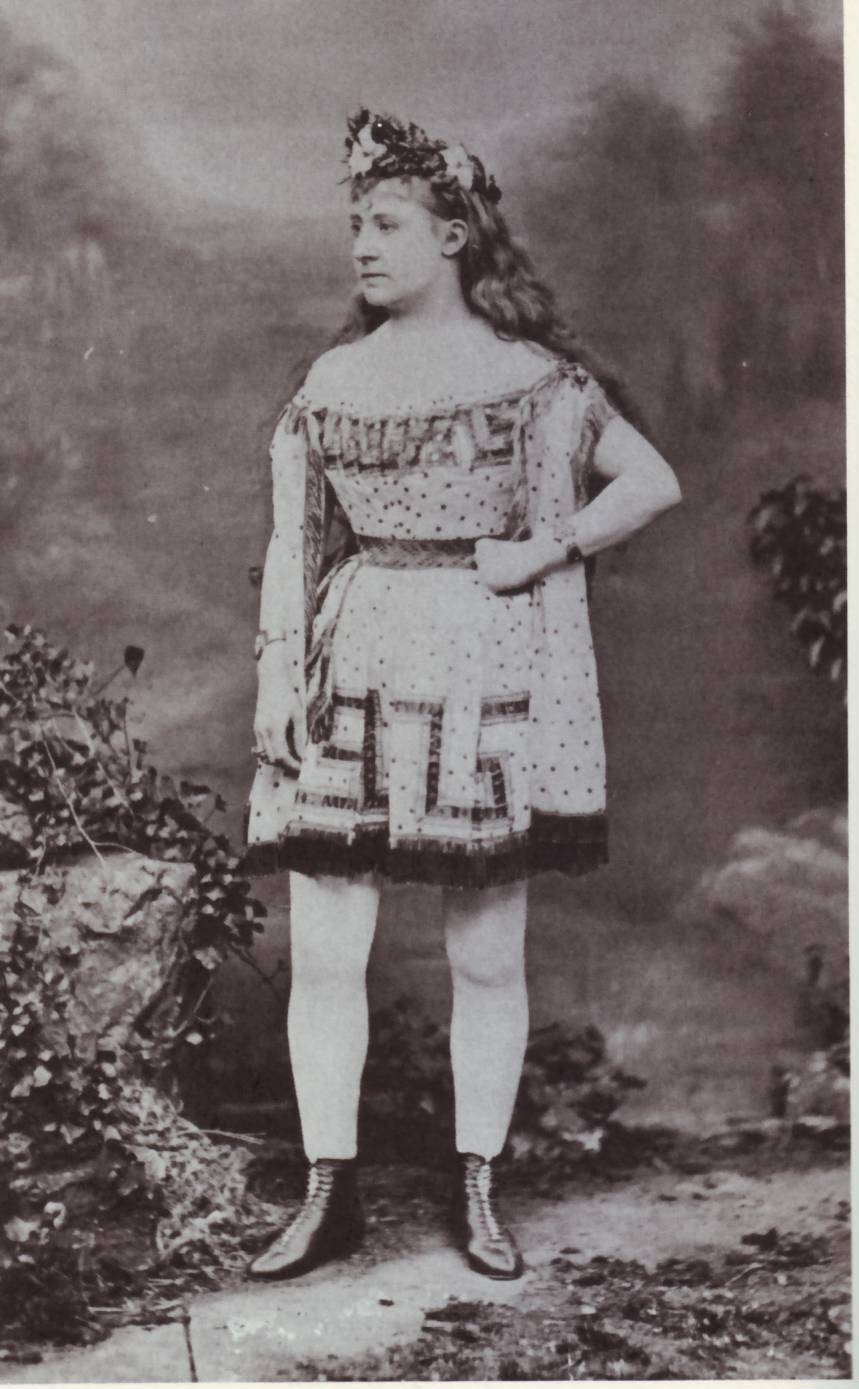

Harriet Pelham as Prince Lollius. (Photo: Kurt Gänzl Archive)

The situation and the season would have been banal, except in that, during the said season, the theatre had a very big hit. After Sophia had appeared as Mme de la Fleury ‘a rich young widow’ in the play Court Gallants, on a program including ‘a duet by the Misses Pelham’, Harriet came out in the supporting role of Jupiter in a new burlesque, penned by the young F. C. Burnand, entitled Ixion.

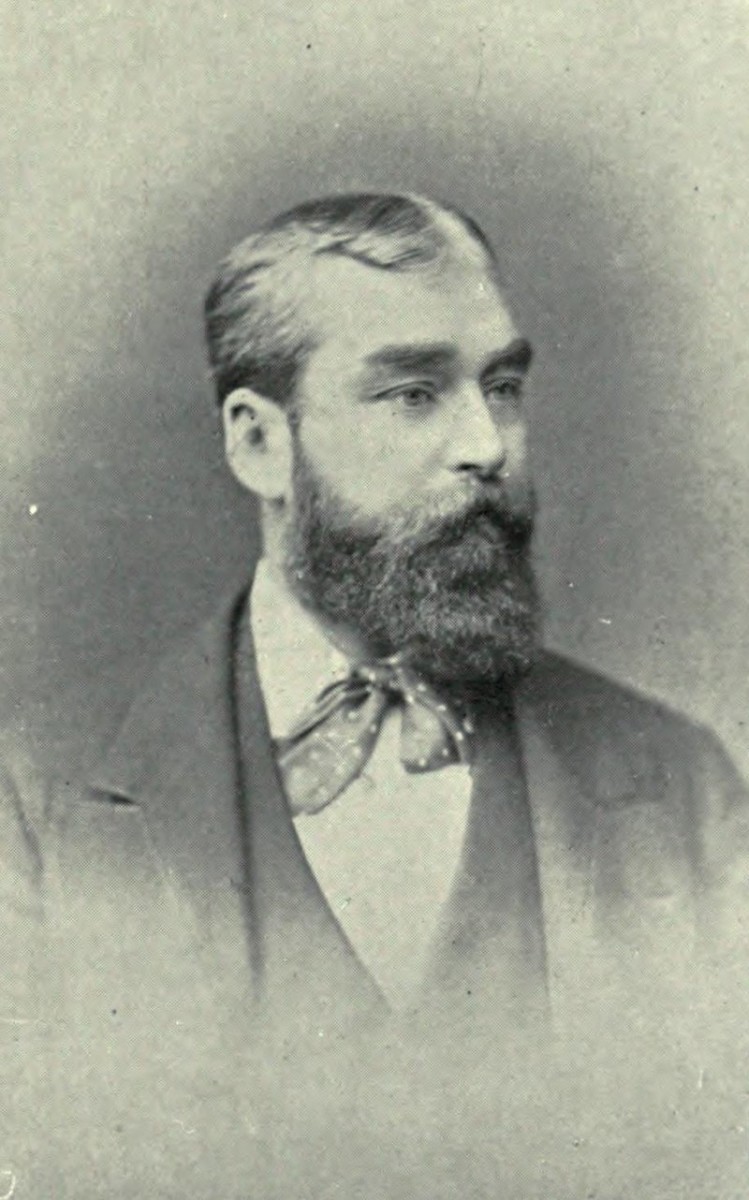

F. C. Burnand in the 1870s.

There was no talk of nerves this time: ‘Miss Pelham’s clear and correct reading is a fine thing for this class of performances’. Sophia was Diana. And Ixion was a major hit. Soon, the Royalty was coining it. And the Misses Pelham were getting exposure. In Madame Berliot’s Ball ‘the sweet voices of the two Misses Pelham’ got special mention, and come Easter 1864, when Ixion finally gave way to a successor in the same line, Rumpelstiltskin, Harriet was the Prince Lollius and Sophia the heroine, Roseken. And discontent brewed in the lap of success.

Mrs. Selby wanted more. More money, more credit. And the girls responded by billing themselves, on the occasion of their Benefit, as ‘responsible manageresses of this establishment’.

So, it all ended up in court, and, when the Royalty reopened, it was now under the management of the Misses Pelham, who were by this time playing Ixion (Harriet) and Mercury (Sophia) in Ixion. ‘The part of Ixion is sustained with great spirit by Miss H Pelham, whose comic dancing is of the most unexceptionable kind, and she is most efficiently supported by Miss Pelham as Mercury, a character that demands a similar talent’. And meanwhile the court cases ran on, with much dirty washing getting an airing.

Mrs. Selby in “Rumpelstiltskin.” (Photo: Kurt Gänzl Archive)

On 22 November 1864, the girls came out as Perky and Flipperta in Snowdrop (‘excellently fitted in their parts’), took part in several plays and then produced another burlesque, Pirithous. All seemed hunk dory. In June, the Royalty closed for the season. And that was that.

The girls were declared bankrupt for 1,544 pounds. Well, it ran in the family. They must still have had an interest in Ixion, for they were subsequently to be seen at the Haymarket, at Astley’s and on the road in the various leading roles of the piece (‘the performances of the Misses Pelham gave every satisfaction for which they were well applauded’). But otherwise, apart from Harriet’s appearance in the 1865 Astley’s panto, they seem to have faded from the stage.

I see them running a stall at the Fancy Fair at the Crystal Palace in 1867, but on stage – in 1868/69 they gave a two handed entertainment Two Does It (‘The dancing of Miss Harriet and the singing of both sisters were much applauded’) which played the Liverpool Monday Evenings, 6 April 1868 – but, otherwise, mostly, starring with the amateurs of the Phoenix Dramatic Club, the Vaudeville Club, and in local concerts. Harriet shows up as a soloist with the Walworth Choral Union, in 1872 they are playing The Waterman with amateurs at Sydenham alongside one G. H. Snazel, and, in 1873, they are on the bill at Wade Thirlwall’s concerts. Harriet sang ‘Una voce’, Sophia ‘Should he upbraid’ and they performed The Woman of Samaria and operatic excerpts. Harriet takes part in the duet ‘Ai nostri monti’. My last sighting of the girls ‘of the Royalty Theatre’ is in an amateur ballad concert at the Horns, Kennington. Back in the amateur world they should never really have left. But for Ixion.

I don’t know what happened to mother and father Parker. Father is still alive in 1878, somewhere, under one of his names. Mother vanishes, but not completely. In 1891 she resurfaces, living with Sophia, and a family historian tells us she died in 1895.

Sophia did all right. On 1 June 1878, 40 year-old former ‘Miss S. Pelham’, now billing herself as an ‘authoress of light literature’, married a 24 years-young civil service clerk, John Forsey. They would have 35 years of married life, during which Forsey rose to be director of the naval stores at the Admiralty and Sir John, Commander of the Royal Victorian Order. And Sophia, thus, Lady Forsey. Sophia died in 1913, her husband 21 February 1915. Half a century on from Ixion.

Harriet was less fortunate. She married the first, in 1875, to a young Wiltshire cheese monger, Edward James Pocock Francis (1845-1925). She died the following year, I assume, in childbirth.

So, Ixion. It’s referred to a lot in theatrical histories. Does anyone know what it, truthfully, was like? Has anyone read it? Has anybody tried to match the lyrics (all printed in the script) to the indicated second-hand tunes? They range from a chunk of Sonnambula and one of Ballo in maschera to old tunes and pop ballads. Oh, I should say that it is drenched in wordplay and rhymes. Well, here’s the script … have a read! (Click here for the complete free facsimile download.)

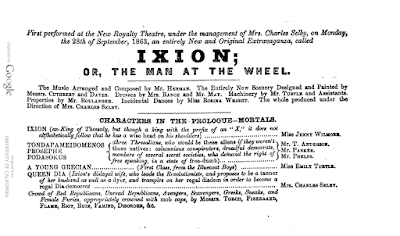

And here is the original cast.

The cast list for the original “Ixion; Or: the Man at the Wheel” production.

Not a lot of names in there that mean much to most people. And even fewer that would have meant anything to an audience in 1863. Unless they’d been kibbutzing at Mrs Selby’s acting classes, whence almost all the damsels came from. But there were some professionals there: [John] Felix Rogers, who played the grande-dame Minerva, and his wife Jane (Jennie) Willmore who took the title-role.

Felix Rogers as Minerva. (Photo: Kurt Gänzl Archive)

A memorist related: ‘The success of the evening was Felix Rogers, as Minverva, a spectacled old crone with a scholarly look about her. I’m afraid to say how many times Burnand’s happy parody of Dr. Watts’s hymn “Let dogs delight to bark and bite” was encored.’

Comic actor Joe Robins, who played Ganymede as the naughty little fat boy, was another who had had a career before and would have more, after Ixion. And the most durable of them all, the established danseuse Rosina Wright, who seems to have been a pal of Mrs. Selby, and who here lead the dancing as Terpsichore.

Then, there was the young actor, Mr. D. James [né David Belasco], born in Eagle Court, the son of a Jewish tobacconist. He had been on the stage for a couple of years, as an extra and then at the Royalty, the previously year (‘plays fops and exquisites very well’), with Joe Robins, and in Jack the Giantkiller, the pantomime, and plays at Birmingham Operetta House, but, cast here as a lively Mercury, he made his mark. However, he jumped ship three months into the run to go to the opposition Strand Theatre, and to jump on the fast track to a famous career.

David Belasco as Mercury. (Photo: Kurt Gänzl Archive)

And now, the girls. Apart from Jenny Willmore, Rosina Wright, and Mrs. Selby herself, it seems all the girls were neophytes. Burnand, decades on, gave some delightful Reminiscences of the Royalty, in Theatre magazine, and it really does seem that he was presented with Mrs. Selby’s ‘class’ and told to pick which ones he wanted for which parts.

Of course, the Pelham girls came first, and Harriet was given the important part of Jupiter. Clara got the much lesser one of Diana.

Harriet Pelham as Jupiter. (Photo: Kurt Gänzl Archive)

Venus, Cupid, Apollo, Juno … the last-named, Mrs. Selby wanted for another of her pals.

Burnand chose for his Venus a lass who insisted that Ada Cavendish was her real name. It almost certainly wasn’t, but I’ve never found out what it was. What also wasn’t real was the mass of long blonde hair which she wore in the role. What was real, was the daringly slit skirt Goddess of Love sported. Ada had stepped on the stage already, in the company at Mr. Nye Chart’s Theatre Royal, Brighton, playing, amongst others, Titania in the Christmas pantomime, so she was a smidgin more experienced than many of her colleagues.

Ada Cavendish as Venus. (Photo: Kurt Gänzl Archive)

The other featured part was cast with the lass named ‘Lydia Maitland’. Real name? Don’t think so. She got the part because Burnand thought her ideal for the boy’s role in the accompanying play. He was right. But she made much more effect as Apollo in the burlesque.

Lydia Maitland as Apollo. (Photo: Kurt Gänzl Archive)

Lydia too had ventured on to the stage before (although her ‘of the Theatre Royal, Derby’ was a bit of a fraud … one night amateur Benefit!) but she had a decade of career before her.

Alas, she also apparently had a decade of ‘living’ – Burnand relates a sad meeting – and she was ultimately reduced to the odd guest appearance with amateurs. I last spot her in 1873, touring in Mazeppa. And then I lose her.

Lydia Maitland and Sophia Pelham in “Rumpelstiltskin.” (Photo: Kurt Gänzl Archive)

Little Marie or Maria Longford was give the role of Cupid. She played it right through the run and I never see her again.

Maria Longford as Cupid. (Photo: Kurt Gänzl Archive)

The role of Juno, that Mrs. Selby had earmarked for her friend, Mrs. St. Henry, went, instead, to one Blanche Elliston.

Mrs. St. Henry, who was no slouch as an actress, would get to play it in revival.

Oh, plenty more Gods and Goddesses to come! Mars was played by a Mr. F. Olivier, who I otherwise spot only in Richardson’s Show at the Crystal Palace, and maybe at Doncaster with ah! Mrs. St. Henry and Joe Robins.

Mr. F. Olivier as Mars. (Photo: Kurt Gänzl Archive)

However, he was another early departure, and his role was taken over by the much more appreciable Fred Hughes, who’d been an auctioneer’s clerk before this, had a good career as a comic actor, as a theatre manager, and as a playwright, and allegedly ‘retired from the stage on the acquisition of a fortune’.

That’s almost my lot, pictorially. But I did dig up a few crumbs on the peasants, villagers and minor deities, down the cast list.

Mr. Charles Lambert, who was cast as Bacchus, was an amateur. He put his nose into the Grecian Theatre for one night, mendaciously billed as ‘of provincial celebrity’, in a famous role, and got torn to tatters by the critics. He went back to Mrs. Selby and the amdrams.

Mr. Phelps, cast in a tiny role, was a loyal company member who got his reward. On the opening night of Rumpelstiltikin, the new actor, hired to play the role of the miller, fell down in a fit backstage and died. Mr. Phelps went on with the book … and kept the part.

Miss Clara Granville (and her brothers), and doubtless al, were Selby pupils, but here’s a surprise … Miss Emily Turtle. That name! Surely Mrs. Selby couldn’t have invented that! And she didn’t. Miss Emily Mary Elizabeth Turtle was the daughter of one John Turtle of Covent Garden. Mama was a dresser and supernumary in a theatre, brother Willie was a gasman in the theatre. Papa was dead. Emily, born 1837, got a job at the Strand Theatre in 1860 (with Marianne Lester!), then progressed to the Royalty … look! Here’s a picture of her. It’s Rumpelstiltskin and that’s Mrs. Selby as the hag. Emily is on our left!

Why do I persist on Emily? Because Emily stuck doggedly to her ‘career’. 1861, 1871, 1881 she is ‘actress’: and by golly she got there. Princess’s Theatre, Adelphi, Crystal Palace and Criterion with Charles Wyndham in the Dickens plays, Aquarium … still going in the profession in 1895, when most of her little Ixion mates were dead, long-retired, vanished … hurrah! for Emily Turtle!

Puzzle. Emily and her old Mum lived together at 17 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden. Is it just coincidence that ‘Mrs. Selby’ died at: 17 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden?

Lydia Thompson as Ixion.

To be continued.

To read the original article, click here.

Please peek at the original (longer) article

https://kurtofgerolstein.blogspot.com/2019/09/ixion-musical-hit-of-1863.html

and if you can give me any help .. most particularly a photo of poor Joe Robins as Ganymede … I’d be so grateful! Kurt