Enrique Mejías García

Operetta Research Center

28 September, 2022

The Jacques Offenbach Society Newsletter has published in its 101st issue (September 2022) a letter from Jacobo Kaufmann entitled “Copyists and Pirates. Some thoughts I’d like to share with Editor Donald Fox”. In this letter reference is made to Enrique Mejías García’s book Offenbach, compositor de zarzuelas. More than that, some serious accusations are waged against Mr. Mejías García. The Opereta Research Center contacted the Spanish researcher from the Centro de Documentación y Archivo (CEDOA) de la SGAE in Madrid. He has resonded to Mr. Kaufmann’s rant, and we publish this response here.

Enrique Mejías García from the Centro de Documentación y Archivo (CEDOA) de la SGAE. (Photo: Private)

Dear Operetta Research Center,

Having tried unsuccessfully to contact The Jacques Offenbach Society Newsletter to offer my version of events and given that the Operetta Research Center has published Mr. Kaufmann’s letter with Donald Fox’s permission, I consider it important that, for reference, my position on the subject can be offered to the readers of your website.

According to Mr. Kaufmann, today we all know how exposed we are to “misinformation and pretend news about things we all know for many years”. Indeed, he points out that “there are so many people who copy articles, statements and books that have been written by others” referring by these “others” to people – we assume, like him – “who after gathering sources, not always available to most people, their extensive research, their hard work and dedication, become the prey of literary pirates”.

With these words, Mr. Kaufmann has tried to relate his book, Jacques Offenbach en España, Italia y Portugal (Libros Certeza, 2007), to my book, recently awarded the Premio de Musicología “Mariano Soriano Fuertes” by the Sociedad para el Estudio de la Música Isabelina.

Jacobo Kaufmann’s book “Jacques Offenbach en España, Italia y Portugal” from 2007.

His argument against Offenbach, composer of zarzuelas begins by attempting to ridicule the title itself, reminding us that “Offenbach has never written or composed a single zarzuela!”.

It’s jocular to have to agree with Mr. Kaufmann, but I’m afraid his assertion tells us that he hasn’t bothered to read my book. It is evident that Offenbach never put his name to a zarzuela score from his own hand; but it should be more evident to Mr. Kaufmann that all his works were performed in Spain and Latin America during the second half of the 19th century by zarzuela companies and adapted as “zarzuelas”.

The book “Enrique Mejías García’s “Offenbach, compositor de zarzuelas.” (Photo: Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales)

My work, from a transnational perspective, focuses precisely on the strategies of acclimatization of French opéra-bouffe in the productive and aesthetic environment of Spanish zarzuela.

Mr. Kaufmann’s most serious accusation and the easiest to dismantle is that, apparently: “almost all of what the author of the university thesis tells us, he has systematically copied from my book, including a list of all the works by Jacques Offenbach produced in Spain, their new versions, arbitrary and assumed translations, imitations, transformations, parodies, and pastiches, seen in Madrid, Barcelona and other Spanish cities, their ‘arrangers’, performers, venues and dates, even the titles I gave to some of my chapters. But he only mentions my name in two little footnotes.”

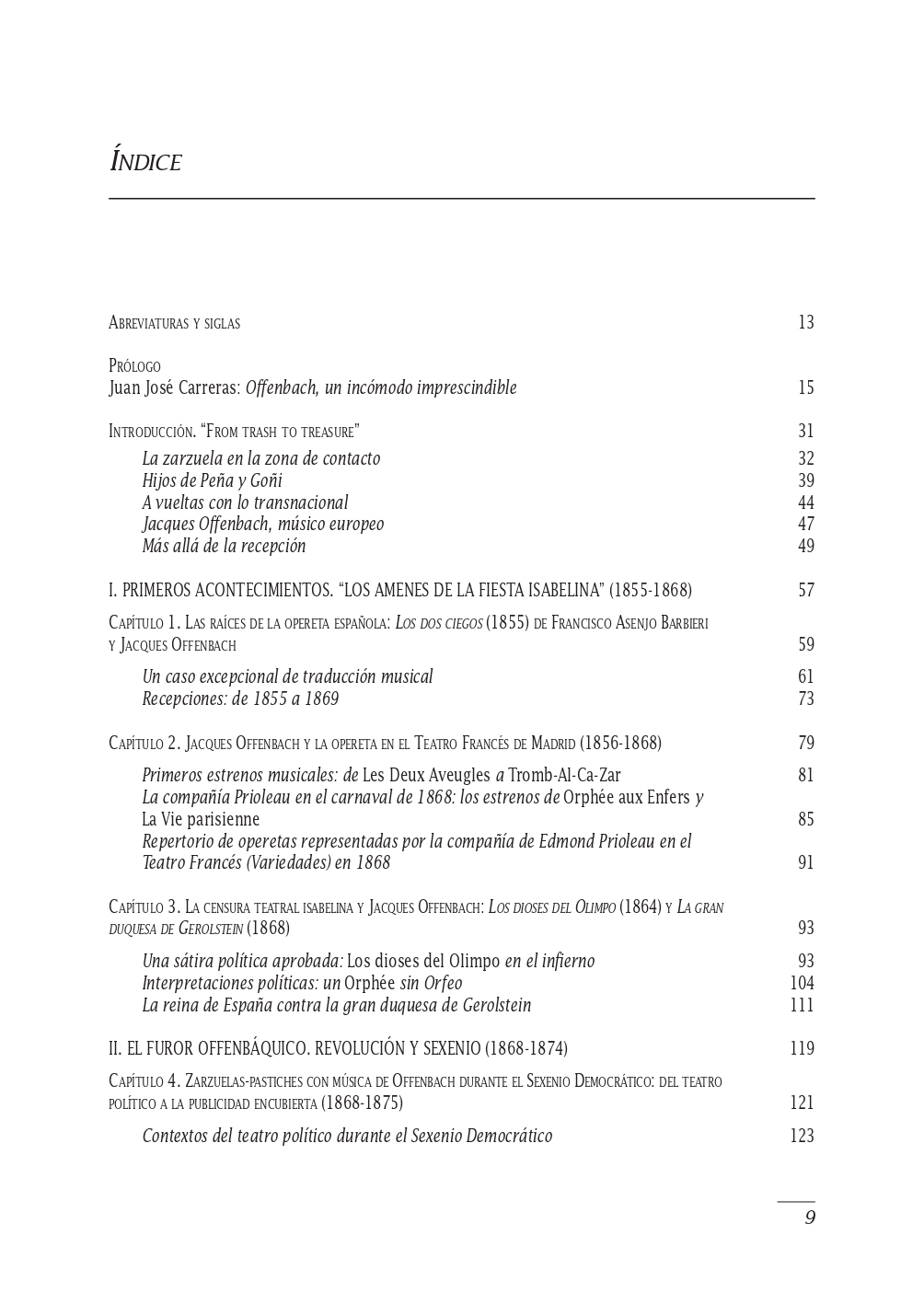

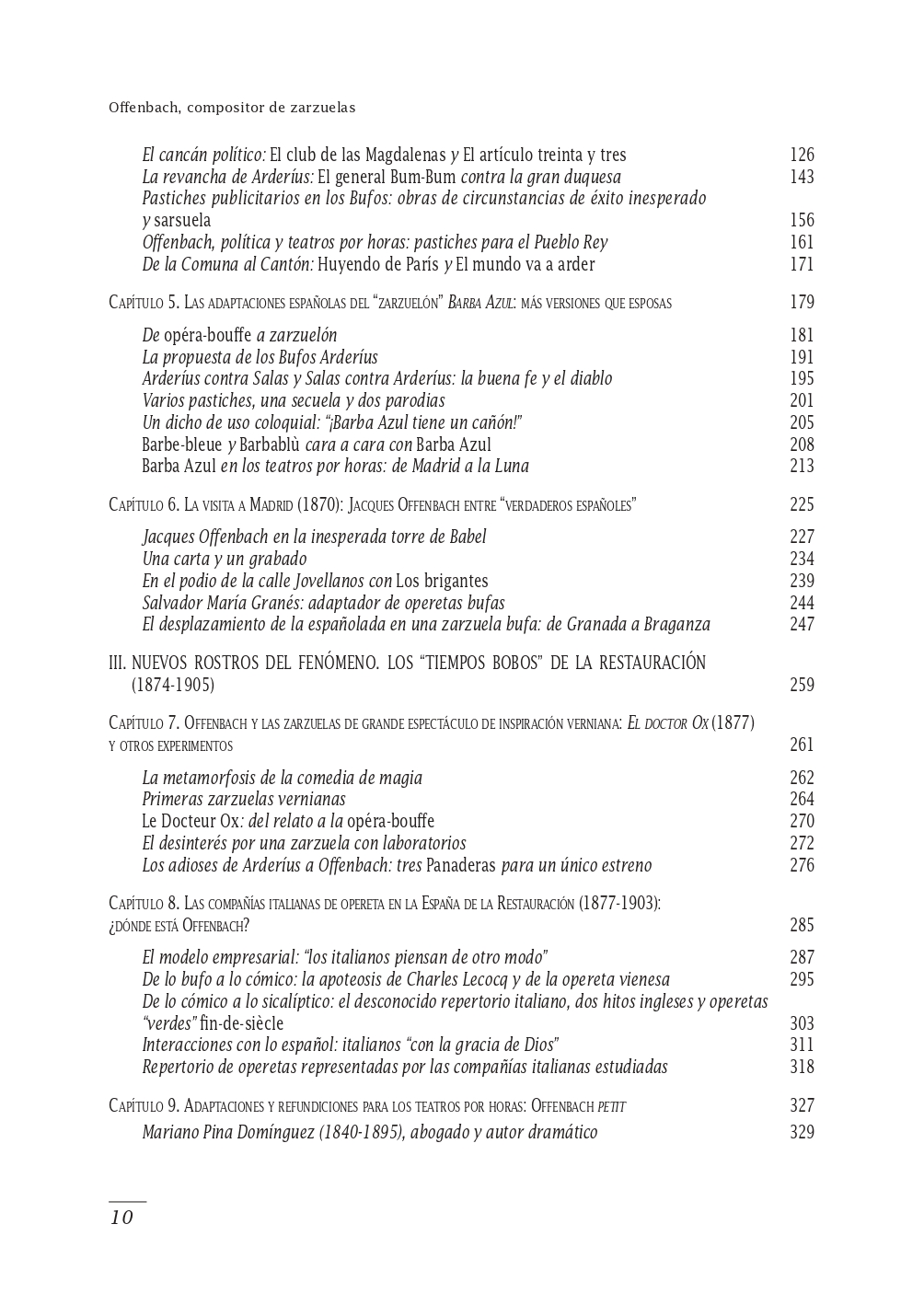

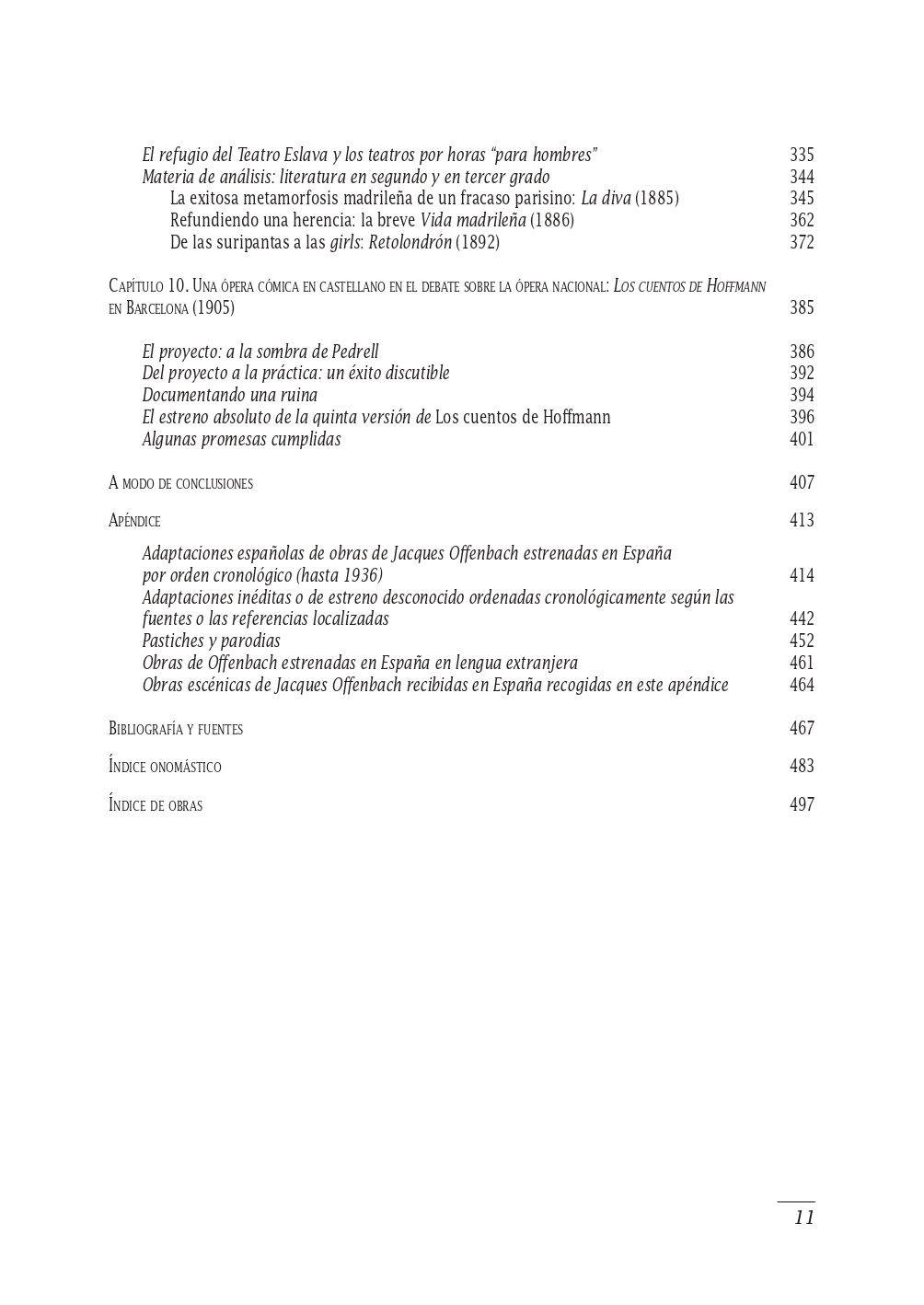

In the first place, none of my ten chapters shares a title with any of his (for the interested reader, I share the table of contents of my book at the end of this letter).

Table of context for Enrique Mejías García’s “Offenbach, compositor de zarzuelas”.

Table of context for Enrique Mejías García’s “Offenbach, compositor de zarzuelas”. (Part 2)

Table of context for Enrique Mejías García’s “Offenbach, compositor de zarzuelas”. (Part 3)

But, in addition, I cite and describe Mr. Kaufmann’s study in stating the question during my “Introduction” (p. 48); I recognize the key points of his research in the chapter I devote to the adaptation of Les Brigands and Offenbach’s visit to Madrid in 1870 (p. 226, footnote) and his book, of course, appears in my bibliography (p. 475).

This is probably one of those typical cases in musical criticism of an author who considers himself the “owner” of a theme. To be frank, I cannot understand this, since Mr. Kaufmann acknowledges that his 2007 book was not written under the sign of musicology.

The aggressive tone of his letter, in fact, is unintelligible since in his book he goes so far as to address the scientific community with the hope that, in the future, it might clarify aspects that he merely points out (p. 127: “No faltará quien aclare la duda”; p. 151: “Más trabajo para los musicólogos”).

The 2018 English version of “Jacques Offenbach in Spain, Italy and Portugal”.

That future has arrived, and with it my humble interest as a musicologist in studying such a transcendental phenomenon using scientific criteria. Perhaps it is worth mentioning at this point that the publisher of my book, the Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales (ICCMU), has been a prestigious institution for decades and that all its publications are subject to a double-blind peer review process.

But if in my book I do not quote Jacques Offenbach en España, Italia y Portugal more extensively, it’s because it’s really difficult to do so.

In his study Mr. Kaufmann presents an absolutely negative scenario where every Spanish adaptation of an Offenbach work in nineteenth-century Spain is presented with hints of illegality and value judgements about the “bad taste”, “aberrations” and “limited genius” of the Castilian arrangers. In fact, it displays no interest in empathizing with a period of undeniable modernity in Madrid’s musical theatre, when almost half of the works of the composer of La Belle Hélène were performed on stage in Spanish.

It goes without saying that in my book I have demonstrated the legality of the vast majority of Offenbach’s adaptations for the Spanish stage, showing how businessmen like Salas and Arderíus or publishers like Vicente de Lalama paid astronomical sums for the acquisition of ownership of countless operettas.

Jacques Offenbach photographed by Nadar in the 1860s.

If the works were re-orchestrated (which was not always the case) it was in adaptations for zarzuela’s orchestra pit, to the same extent as when the same works arrived in the operetta theatres of Vienna (think, for example, of Millöcker’s arrangement of Le Docteur Ox).

Another aspect of Mr. Kaufmann’s book that makes it difficult to quote is that it leaves open to assumption such a fundamental question as the identification of works adapted into Spanish and/or supposedly premiered in Spain. It is no longer an issue of leaving questions in the air, as we mentioned above, but in several cases, premieres are assumed in his book’s narrative that either did not take place, or of which we cannot be certain.

Matilde Franco, probably as Queen Ananás in “Robinson Crusoé” by Barbieri. (Photo: Memoria de Madrid – Ayuntamiento de Madrid)

As it was the only Spanish reference on the subject of Offenbach’s reception in Spain, Italy and Portugal, the book became a minefield in which every piece of information had to be examined with caution. Mr. Kaufmann, who believes himself to be the exclusive owner of the available data of Offenbach’s Spanish adaptations, their casts, etc., could have been much more careful in this respect.

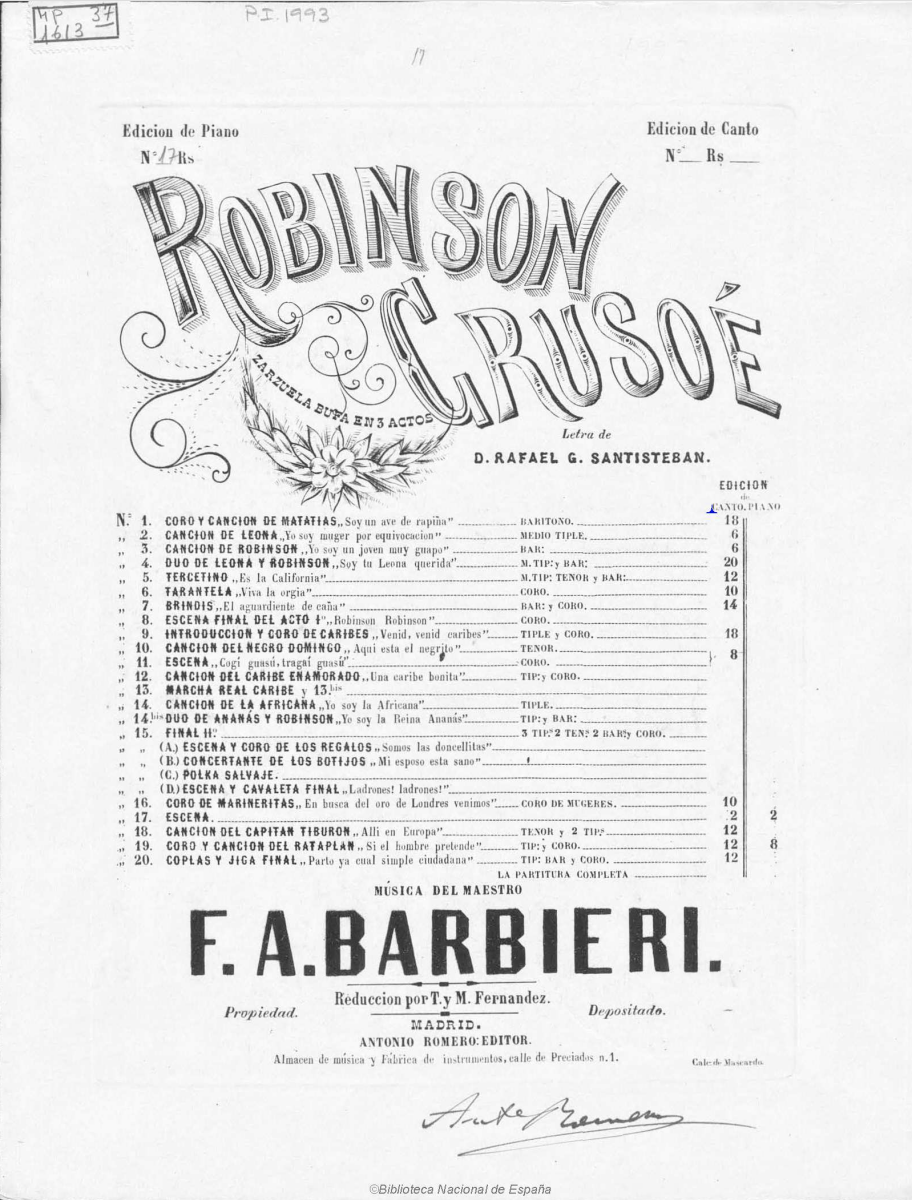

Vocal score of Barbieri’s “Robinson Crusoé,” first performed at the Teatro de los Bufos on 18 March 1870. (Photo: Biblioteca Nacional de España)

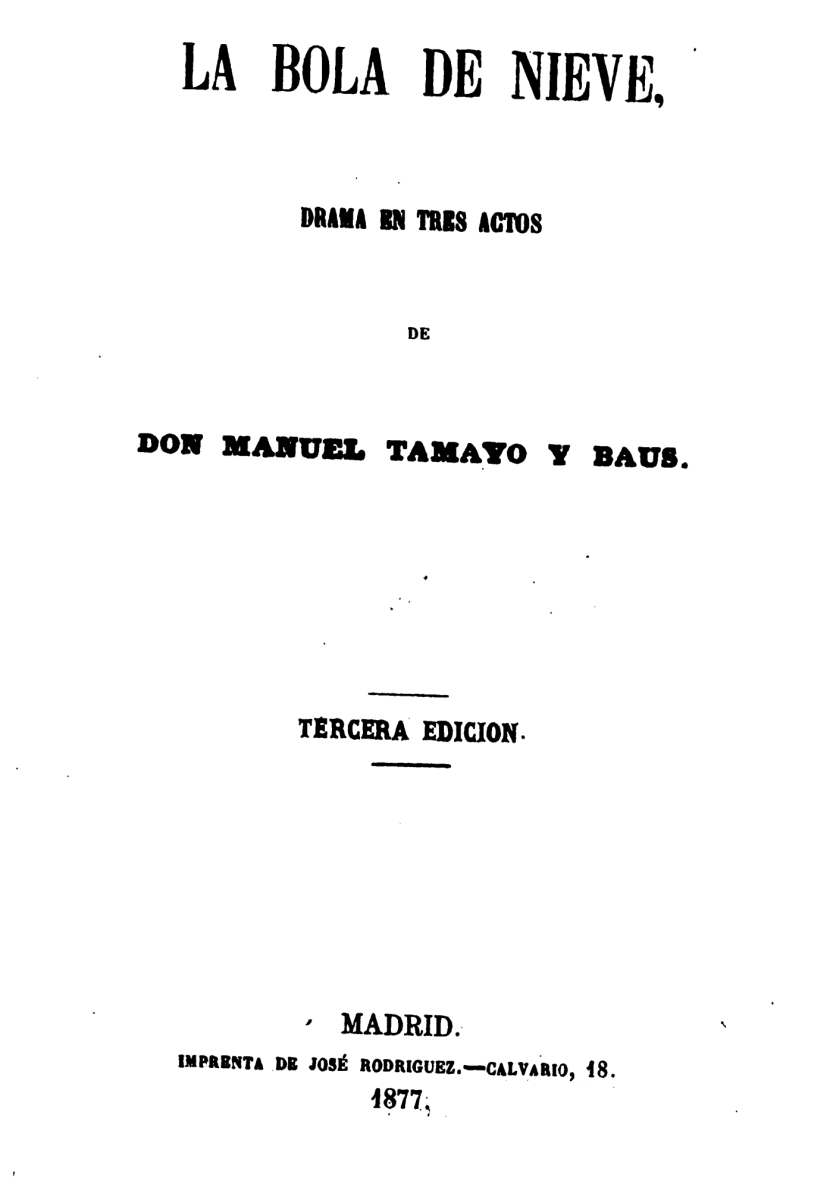

To give just several examples, it is inadmissible to confuse the premiere of Barbieri’s Robinson Crusoé with Offenbach’s work, which was never performed in a Madrid theatre (p. 87); the same goes for a revival of Tamayo y Baus’s drama La bola de nieve in 1871, which has nothing to do with the homonymous opéra-comique, unpublished in Madrid (p. 128).

Libretto of Tamayo y Baus’ “La bola de nieve”, a drama from 1856 reprised in 1871 at the Teatro Eslava, Madrid. (Photo: Biblioteca de Catalunya)

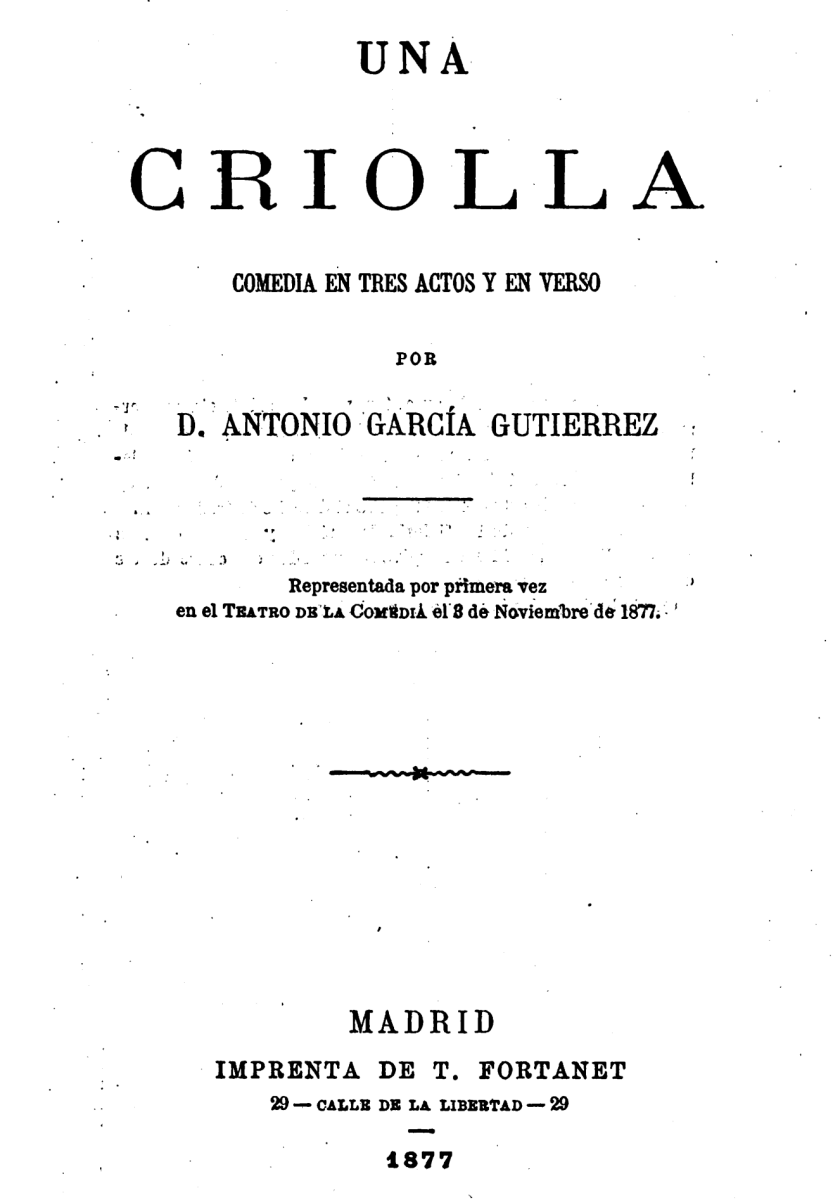

The adaptation of La Jolie Parfumeuse as Rosa never made it to the stage, as Mr. Kaufmann claims (p. 141); the La criolla premiered during 1877 in Madrid is García Gutiérrez’s comedy Una criolla and it has nothing to do with La Créole, another opéra-comique whose Spanish adaptation also remains unperformed (p. 142).

Libretto of García Gutiérrez’s “Una criolla,” first performed as La criolla at the Teatro de la Comedia, Madrid, on 3 November 1877. (Photo: Library of the University of Illinois)

La feria de san Lorenzo is a zarzuela with an entirely original score by Manuel Nieto, not Offenbach, although Pina Domínguez’s libretto adapts Crémieux and Saint-Albin’s for La Foire Saint-Laurent (p. 146); finally, Carabineros y contrabandistas cannot be identified with Maître Péronilla because it is, in fact, one of the three Spanish adaptations of Les Braconniers (p. 165).

Libretto of Pina Domínguez and Nieto’s “La feria de san Lorenzo,” an entirely original new score. (Photo: University Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

To conclude with another example, Mr. Kaufmann ends his letter to The Jacques Offenbach Society Newsletter by transcribing an excerpt from his book in which he recounts the premiere of the Spanish adaptations of La Vie parisienne.

He begins by saying that “The first to present La Vida Parisiense was the Bufos Madrileños at the Circo de Paul during nine days in December 1868″, but – sorry, amigo – it was not Meilhac, Halévy and Offenbach’s opéra-bouffe at all, but a short ballet (baile) with the same title!

As a matter of fact, La Vie parisienne had been performed in Madrid months earlier, in May 1868, by Edmond Prioleau’s Company at the Teatro Francés. This information, by the way, is not recorded in Mr. Kaufmann’s study.

At its publication in 2007, Jacques Offenbach en España, Italia y Portugal had the bravery to draw attention to a phenomenon whose impressive scale was apparent. However, Mr. Kaufmann’s contribution of data (as we can see, not always reliable) does not give him ownership of such a vast and fabulous subject.

I must remind you that other musicologists have already studied the receptions/adaptations of operetta in Spain and Italy, such as Ignacio Jassa Haro [1] or Elena Oliva [2]. Intellectuals whose first-class work – also based on data and sources – motivates me to get on board, as a colleague of theirs, in the same boat, which is not exactly a pirate ship.

For those, frankly, I’d prefer to stick with The Pirates of Penzance; Or, The Slave of Duty ending with these verses: “Still, perhaps it would be wise / not to carp or criticize, / for it’s very evident / these attentions are well meant.”

Pirate symbols. (Photo: Rowan Heuvel / Unsplash)

Footnotes:

[1] Ignacio Jassa Haro: “Con un vals en la maleta: viaje y aclimatación de la opereta europea en España”, Cuadernos de Música Iberoamericana, 20 (2010), 69-128. Online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/CMIB/article/view/59645

[2] Elena Oliva: L’operetta parigina a Milano, Firenze e Napoli (1860-1890). Esordi, sistema produttivo e ricezione. Lucca, Librería Musicale Italiana, 2020.