Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

14 August, 2017

If you grew up as a kid in Germany, you probably learned early from a famous TV program to always ask “why” – with a popular jingle that went “wieso, weshalb, warum, wer nicht fragt bleibt dumm.“ It roughly translates as “if you don’t ask why you will remain dumb.” Well, in terms of operetta this central “why” question is asked far too rarely, otherwise we’d have more discussion. Which has been surprisingly mute for years. But when I received the new budget box set of Der Graf von Luxemburg, recorded live at the Opera Frankfurt on New Year’s Eve 2015/16, I couldn’t help asking myself “why” many times over. Let me start with the version recorded here: it’s the 1937 edition that originally premiered at the Theater des Volkes (Charell’s former Großes Schauspielhaus) in Berlin, conducted by Lehár and loudly applauded by propaganda minister Goebbels.

The cover of the OEHMS Classics “Der Graf von Luxemburg,” 2017.

In the booklet to the new (attractively packaged) double disc, Frankfurt’s opera dramaturg Norbert Abels mentions the choice of version in an aside. No explanation is given why he or any of the other people in charge in Frankfurt opted for the re-write from Nazi times, instead of performing the internationally successful original Viennese version from 1909. In another aside, the OEHMS Classics booklet states that they are using the “dialogue version by Dorothea Kirschbaum, based on the second version [of Graf von Luxemburg] that premiered on 4 March, 1937 in Berlin.” (Interestingly, there is no dialogue included on this recording, but I’ll get to that in a second.)

If we look up the performance history of Graf in Stefan Frey’s book Franz Lehár und die Unterhaltungsmusik im 20. Jahrhundert, we learn that after nearly two decades of international success – in France, England, the USA, Italy, even Australia – Lehár rearranged the show for Nazi Germany, adapting it to the new ideals after 1933. The most obvious difference was that the two Jewish librettists – Robert Bodanzky and Alfred Maria Willner – were not mentioned on the playbill anymore. They simply disappeared from sight.

The 1940 program book for “Der Graf von Luxemburg” at the Theater des Volkes in Berlin.

The new production was presented as a “Kraft durch Freude” event, since Goebbels used the Theater des Volkes for (t)his mass organization. He states in his diary, that the staging was “very colorful and amusing.” The workers in the audience “were enthusiastic, which is always good.”

Just before opening night in 1937, Lehár had travelled to Berlin for the first time in four years to attend the 9th Composers and Authors Conference. There, he met Goebbels, but also Hitler at a concert at the Philharmonie. Hitler was overwhelmed by encountering his “favorite composer,” and he attended a Berlin performance of Zarewitsch with Lehár conducting a few nights later. (Where the still living Jewish librettists were mentioned on the playbill!) The Führer’s very public appraisal of Lehár quickly turned the composer into the “celebrated grand master of operetta in the Third Reich,” Frey states.

Of course, all of this is fascinating operetta history. It’s also very typical operetta history. And it deserves full attention. To mention it in an aside, as an explanation for why this “Aryan” version was chosen over the original, makes me want to scream: “Are you serious?”

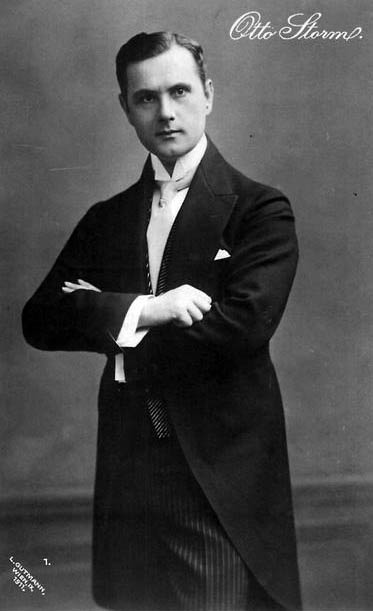

Otto Storm who sang the title role of “Der Graf von Luxemburg” at its world premiere in 1909.

If you check out Graf von Luxemburg on Wikipedia, you read that this 1937 version is the one “preferred today.” Why is it preferred? Is it because it’s the version most easily available through the publisher, who got fully updated performance material in Nazi times that replaced the “degenerate version” from before? Does no one want to bother with a reconstruction of the 1909 Vienna version, or any of the foreign language versions? Can it be that simple?

If, after some archive searching and comparing of versions anyone still thinks the 1937 “Fassung” is the artistically or musically ‘better’ one, then that would be worth a few lines of explanation in a booklet. I think. For example: what makes the 1937 version different from the 1909 one? Other than the fact that the opera tenor René in 1937 was Hans Heinz Bollmann and the libretto was re-worked by Wolf Völker?

Talking of re-working: why hasn’t the later 1941 version by Heinz Henschke been considered? It premiered at the Metropoltheater in Berlin and starred Johannes Heesters as René and Else Schulz as Angéle, Werner Schmidt-Boelcke conducted. Which version did Hubert Marischka use in 1929 when Graf von Luxemburg was given at the Theater an der Wien with Maria Jeritza as Angéle and Ossi Oswalda as Juliette, plus Mizzi Zwerenz as Kokozow?

Operetta and movie star Ossi Oswalda.

We might never find out, because when it comes to operetta it seems enough to hear a happy waltz, and forget about everything else.

Allow me to ask another “why”: OEHMS has issued this performance on a double disc, the first of which has a playing time of 35 minutes, the second 51 minutes. It would have been easy to accommodate some – maybe all – linking dialogue. (In the re-written version by Dorothea Kirschbaum.) Instead, Lehár is reduced here to a “Wunschkonzert” performance where every musical number is treated like a little operatic gem. This is a total contrast to the approach Adam Benzwi has cultivated at the Komische Oper recently with Abraham and Oscar Straus: Benzwi always allows the music to emerge out of the dialogue and to fade back into dialogue. This elevates the status of the spoken word and turns operettas into dramatic works, rather than a string of songs with no plot relation.

(I could say, of course, that the idea of ignoring the plot and dialogue and focusing exclusively on the narcotic quality of the music was also a Goebbels approved ‘invention’ from Nazi times. It managed, against all odds, to live on.)

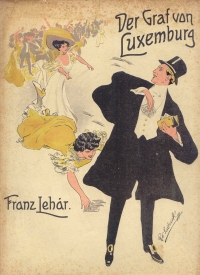

Sheet music cover for “Der Graf von Luxemburg.”

And the last “why” is this: if the 1937 version for opera tenor is used, why does the CD cover show a sheet music cover from the 1910s? Why is the Parisian Belle Epoch charm of the show praised in the booklet, but we are not getting a ‘French’ style performance, but a dramatic Finnish soprano as Angéle (Camilla Nylund)?

All of these aspects would be worth discussing. Instead of just sitting back and enjoying the oftentimes impressive renditions of the songs. Mention should go to Daniel Behle’s fresh René (not in the Heesters tradition of mellow operetta singing!) and Sebastian Geyer as Count Basil Basilowitsch. His act 1 song “Ich bin verliebt, ich muss es gestehen” is my personal highlight on this recording. While Louise Bode as Juliette – a role created by Louise Kartousch in 1909 – remains the modern-day opera singer skipping over every naughty little detail in the lyrics. The text talks about men staying “hungry” and waiting for “desert.” But here, it’s all about the production of lovely tones. You have to guess what the original fun and effect of such-like numbers was, and why Kartousch was such a celebrity. It had nothing to do with her pure soprano singing.

Louise Kartousch and Bernhard Botel in “Der Graf von Luxemburg,” 1909.

What you do get, on these discs, is a lot of applause after every number. The audience seems to have enjoyed itself. And the highly energetic conducting by Eun Sun Kim and the Frankfurter Opern- und Museumsorchester is an interesting novel approach to the score that’s well worth investing 20 Euros.

As with the various new DVD versions (with Bo Skovhus as an even more ‘operatic’ big-sing high baritone René) this release misses the opportunity to answer any questions that surround Graf von Luxemburg. Since Norbert Abels, the Frankfurt dramaturg, is a very clever man and very knowledgeable about operetta (remember his Rössl essay?) I’m sure he could have given some answers. And I would have enjoyed hearing/reading them.

Because getting answers to “wieso, weshalb, warum” can enhance the joy of operetta – even of a Lehár operetta!

Fascinating! There is another version not mentioned above; that in English for the production at Daly’s Theatre, London, which opened on 20 May 1911. This version by Basil Hood (Merrie England) and Adrian Ross was in two acts rather than three, and Lehar not only conducted the premiere, but also composed several new numbers including “In Bohemia” and a duet “Cousins of the Czar. In addition Lehar incorporated some music from Wiener Frauen, including the waltz theme sung to Angele by an unknown tenor admirer at the end of “Daydreams, you must go”. There is a recording with June Bronhill, conducted by Vilem Tausky, which also includes Max Schoenherr’s overture.(Classics For Pleasure 724357599627).