Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

6 March, 2018

Leo Fall’s one-act operetta Brüderlein fein premiered in the notorious basement cabaret of the Theater an der Wien, called “Die Hölle,” in December 1909, as an “Alt-Wiener Singspiel” by Julius Wilhelm. It tells the unusually ‘chaste’ story of a 40th wedding anniversary of church musician Josef Drechsler and his wife Toni. While they sit down to eat a festive Guglhupf, ‘Youth’ walks in and gives them an hour ‘back then’: the night of their wedding. Suddenly they’re young again, swirling around to a grand Leo Fall waltz tune. Originally, this little show was played by a small band consisting of clarinet, piano, cello and two violins. It was a hit in the midst of the usually more frivolous late night Hölle entertainments. A year later, Leo Fall adapted the show for full orchestra and presented it at Vienna’s Carltheater with Alexander Girardi as Drechsler and with Mizzi Günther as Toni. It couldn’t have been a more star-studded performance…. Especially since Girardi was specialized, by this late stage of his career, on nostalgia roles. (Comparable to Kalman’s Zigeunerprimas, which he premiered two years later.) Now, the label cpo has presented Brüderlein fein in the full orchestra version on CD, a recording made in 2012 in Cologne by the radio station WDR.

The CD cover of Leo Fall’s “Brüderlein fein” from Cologne, 2012. (cpo)

The show needs atmosphere to make an impact. It’s a bitter-sweet tale of a world that’s long gone: the world of Old Vienna 1850. Or, as an exhibition once claimed Old Vienna: The City That Never Existed. Such nostalgic pieces became very popular after World War 1 when audiences distressed by the radical social and cultural changes longed to go back to a ‘secure’ world of yonder. Leo Fall and librettist Julius Wilhelm were a bit ahead of their time here. But they were ahead with a wink in their eyes, because the presentation of ‘Youth’ as a semi-nude cupid playing a gold violin was rather typical for Die Hölle. And Mizzi Günther (the world’s first Merry Widow) as Toni-turning-young-again was not without its visual attractiveness either, especially when she led her husband to the bedroom to relive their wedding night once more. They do so dancing a Jubilee Waltz that Drechsler composed back then in celebration of their union. It contains the lovely advice “nicht zu schnell und nicht zu langsam” (not too fast and not too slow) and calls a perfect waltz “the highest form of spinach” (“der höchste Spinat”). If that isn’t self-irony by the grand-master of Viennese waltzes, we don’t know what is!

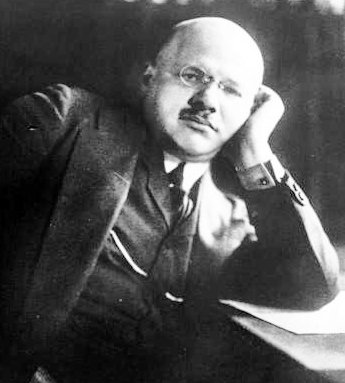

Composer Leo Fall in 1915.

As the story unfolds, the audience is taken through various Old Vienna settings: the Stephansdom, an old street with vendors, a kitchen where the Guglhupf is coming out of the oven. Such scenes were highly popular back in 1909/10 as tourist postcards representing Vienna as a kind of Disneyland. Not much has changed, you might say, if you think of the endless Sissy and Johann Strauss postcards today.

A typical street scene from Vienna pre-1900. (Photo from the catalogue “Wiener Typen,” Wien Museum 2013)

The Cologne radio broadcast starts out promisingly with lovely orchestral playing from the WDR Funkhausorchester Köln, conducted by Axel Kober. The “musical prologue” (7 minutes) is an amusing mash-up of many famous tunes, taking us back to olden/golden days in a time warp. But then the problems start, because the newly written linking texts by Jens-Uwe Völmecke – narrated by Henning Freiberg with the emotional distance of a news presenter – are as bland and irony-free as can be. They certainly do not set the stage for any time travelling worth that name. They are embarrassingly banal.

Alexander Girardi playing a father-figure in Kálmán’s “Zigeunerprimas.” (Photo: Archive Marion Linhardt)

Sadly, the three singers don’t make up for this. None of them displays acting talent, meaning they are just singers who sing, no emotional shading of any kind can be heard. While Andrea Böning as ‘Youth’ has a lovely straight forward voice, the two big roles are taken by singers who do not sound too happy in front of a microphone: especially Anke Krabbe as Toni produces sharp and strained tones. While Michael Roider as Josef warbels along, but that’s it.

Mr. and Mrs. Drechsler, after 40 years of being together, are a bit like Tevje and Golde in Fiddler on the Roof. But there is none of the “Do You Love Me?” closeness or emotional depth in the performance of Krabbe and Roider. They are neither convincing as ‘the old folk’ nor as their younger selves.

This is a typical problem of WDR operetta performances, and a typical problem of cpo CD issues: the casting. The radio representatives stick to their so called traditional ideal of ‘classic opera singers,’ even though neither Mizzi Günther nor Alexander Girardi were opera singers; nor were Viktor Nobert and Mimi Marlow, the 1909 original Hölle cast. (So how can anyone claim that such casting is ‘traditional’?)

I don’t know what it needs to get WDR and all similar radio stations performing operetta (Bayerischer Rundfunk et al.) to re-think their standard casting of such shows….. it’s not that there aren’t hoards of great singing actors and actresses out there in Germany and Austria who could easily make such a sentimental story an interesting and rewarding affair, as a powerful meditation on youth and the passing of time. But with flair and possibly even a few sexual kicks. It is a cabaret operetta, after all.

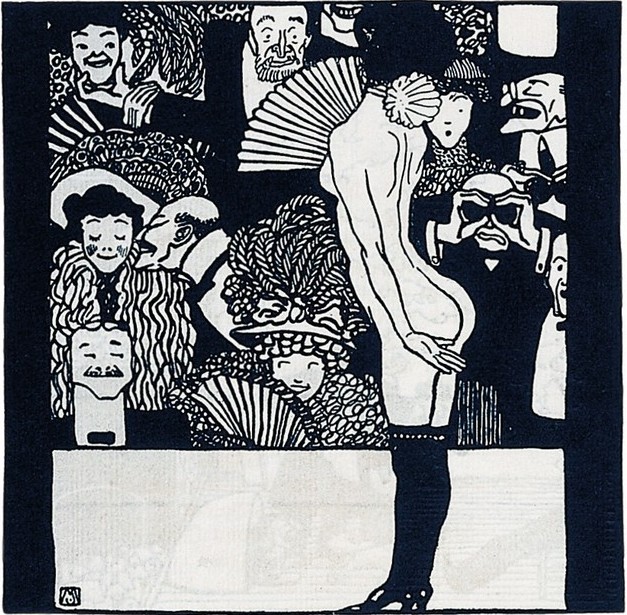

Moriz Jung’s illustration for the operetta cabaret Fledermaus in Vienna, 1907.

The way the whole thing is done here is like an echo of radio programs from the 1960s and 70s, but without the better singers WDR had back then. Operetta directors elsewhere have shown, in recent years, that there is another way of approaching the genre. But this new approach has not reached German state radio stations, nor the people at cpo. Which kind of disqualifies cpo as a serious operetta label.

Just for the record: Brüderlein fein went around the world, all the way to Buenos Aires, Oslo, Riga, and Zurich. It also had an English language career. In London it was presented as Darby and Joan at the Coliseum in 1912, a US-American version entitled Joys of Youth was prepared by John A. Bassett. It doesn’t seem to have premiered, though. At least Stefan Frey mentions no theater and performance date in his biography Leo Fall: Spöttischer Rebell der Operette.

There have been various radio recordings in the past, from Stuttgart (1949) and Vienna (1953), Franz Marszalek even recorded the work with/at WDR in 1966 with Ferry Gruber and Gretl Schorg. What exactly the bonus of this new WDR version is supposed to be is anyone’s guess. It’s labeled as “The Cologne Broadcasts.” Which might not be the most convincing label a modern operetta recording can have.

A piano score for Leo Fall’s “Brüderlein fein,” showing the rejuvinated Mr. and Mrs. Drechsler.

Considering that the orchestra sounds lush and grand, it really is a shame that the casting department did not give Axel Kober more suitable performers. (Or didn’t he ask for them?) For anyone interested in discovering Leo Fall’s witty and (a)rousing music, this Brüderlein fein is not a good way to start. Sadly, the other Leo Fall issues by cpo aren’t a good introduction either. Which makes it somewhat questionable what this CD series is there for in the first place?

For a more convincing trip to Old Vienna, I recommend the catalogue Wiener Typen: Klischees und Wirklichkeit issued by Wien Museum in 2013. It puts this one act operetta into context and shows you what these Old Vienna characters looked like, it’ll make you understand why such shows were so beloved – pre- and post World War 1. And thankfully the many historic Leo Fall recordings available on YouTube today point the way to how it should be done – because ‘traditional’ casting à la cpo and WDR is not doing Leo Fall a favor. It’s not doing the memory of Alexander Giradri a favor either.

When will folk learn that Bigger isn’t Better ….

They don’t even have ‘big voices,’ just trained opera voices. And, yes, the chamber version would have been interesting too. But the orchestra sounds lovely here, since Leo Fall was a master orchestrator.

ORF holds a complete “live-in-the-studio” recording that likely has never seen the light of day after the original broadcast on New Year’s Day 1953. Under the baton of Hans Hagen, three true veterans (all in advanced age at the time) are heard: Betty Fischer as Tony, Pepi Kramer-Glöckner as Gertrud, and Hubert Marischka as Drechsler. I have no idea of course whether these three septuagenarians succeed even modestly to suggest the rejuvenation, but for authentic style this should be a reference version. The only bit from it I’ve ever heard (Betty Fischer’s Guglhupf song) certainly shows the old lady in very good voice. Maybe CPO would have done well to send ORF’s in my experience unfortunately very lethargic staff burrowing for it, rather than making such a generic recording with a cast that has no noticeable relation or special sympathy at all for Vienna operetta style of the early 1900s.

It’s kind of amazing to know that such a treasure exists, it could even be published without any copyright problems. But instead a new version is performed and released, just because it’s ‘new’? I would love (love!) to hear Fischer and Marischka. They are one (and two) generations older than Günther and Girardi, but the are from the same ‘tradition’ and same Theater an der Wien ensemble.