Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

29 May, 2021

The US-American musicologist Micaela Baranello joined the Department of Music at the University of Arkansas in 2017 and has recently published her research project The Operetta Empire. It’s a study of how operetta represented questions of nation, class, and gender in early 20th century Vienna. She is also an author for The New York Times, where she contributes features and reviews to the Arts and Arts & Leisure sections. We spoke with her about her fascination for operetta, sex and sentimentality in the genre, and how this form of popular musical theater has become part of Twitter debates.

Micael Baranello’s “The Operetta Empire.” (Photo: University of California Press)

Hello, Miss Baranello. Thanks for taking the time to talk with the Operetta Research Center. A new English language book on operetta at a big university press… congratulations! It comes after there have been many publications on the genre in German in recent years and countless Anglo-American studies on Popular Musical Theater. Why was there such a long pause after Richard Traubner’s 1983 Operetta: A Theatrical History? And what stirred the new interest?

As you note, my book is from an academic press, and I’m an American musicologist. In the last decade or so, musicologists have become more and more interested in studying how we construct the idea of “classical” and “popular” music (E- and U-musik in German), and I think one reason operetta is interesting is because it tests these boundaries so frequently. There are certain composers, like Lehár, want to be heard as composing serious music, but because of the places where their music was performed (and because of elements of its style), that was never going to happen, he was always going to be the music version of nouveau riche.

Richard Traubner was invested in the idea of proving operetta as worthwhile; he spends a lot of time separating what he thinks are good operettas from what he thinks are bad. That’s not my project, but I’m interested why so many operetta scholars have always been trying so hard to get a certain kind of respect from people who are never going to give it to them. That’s what makes operetta middlebrow.

Traubner (in)famously defined the genre as “sentiment and Schmalz,” which is probably how many Americans saw operetta between the 1920s and 80s. Can you relate to that definition? Is it still appropriate?

Unlike Traubner, I like sentimentality, let me feel my feelings! Traubner, and even more so his German semi-counterpart Volker Klotz, seem very uncomfortable with the idea of operetta as entertainment and want to construct it as a place of satire, compositional craft, or some other kind of rigor (there’s a strong gendered aspect to this: always men fearing that this is for the ladies). Satire is an important element of operetta history too, but for my subject, the Vienna in the 20th century, it’s hardly the only or most prominent one. Pleasure and ease and style are just as important. But I do think that those elements sit uneasily with modern attempts to perform operetta, because they date very quickly and are attached to elements of the performance not necessarily contained in the score and libretto. If you’re performing one of these works you need to think critically about why you’re doing it and what kind of entertainment you’re providing to your audience.

An early edition of Richard Traubner’s book “Operetta: A Theatrical History.”

You chose Vienna as your focus for examining the genre. What’s special about Viennese operettas for you and for English language readers? As opposed to Broadway operettas, Berlin operettas, French operettas etc.?

For me, Vienna is particularly interesting because of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (that is, the state between 1867 and 1918): its multinationalism, its particular lateness, and the intense nostalgia that memorializes it (which is why I also discuss operettas from the 1920s). My first academic exposure to this subject was a course I took in college taught by Dr. Pieter Judson, a scholar of nationalism in Austria-Hungary. The following year, I studied abroad in Vienna and as a music student learned all about Mahler and Schoenberg and Bruckner and so on.

But I also found all these delightful operettas being performed at the Volksoper and I couldn’t read much about them in English. The particular structure and ethos of the empire is all over them too, just like Mahler, even as that imperial imprint is competing with more cosmopolitan, modern elements (“Kaiserstadt und Metropole,” as Marion Linhardt puts it). I think all those other subjects are also interesting too, but that’s what led me to Wien! (For more information on Marion Linhardt’s research, click here.)

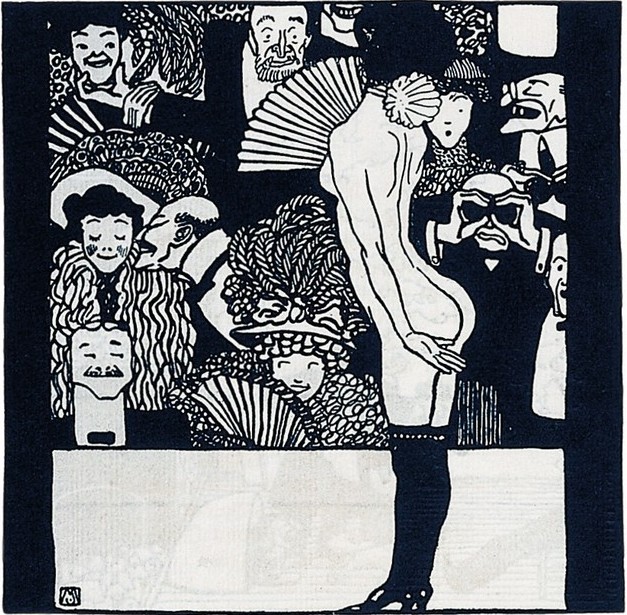

When operetta first came to Vienna, as an import from Paris, it provoked moral outcry: Offenbach’s pieces were described as inappropriate and indecent, the actresses sold nude photographs of themselves and appeared more or less nude on stage, there was a lot of gender confusion and sexually explicit content, and it was all presented in an over-the-top and extreme way. In his novel Nana Zola even has the director of the Théâtre des Variétés call his venue a brothel. Theater an der Wien had a brothel right next to its stage door. How important was such a sexual aspect for the success of the genre – in Paris, Vienna, but also London and the USA? How important is it in defining what operetta is, as opposed to Singspiel or opera? And why don’t you discuss “sex” in your book? Is it American prudery?

That would be a great topic for a book, but it’s not the book I wrote! My book does not attempt to be comprehensive or discuss everything about operetta during this time period: I’m analyzing a certain discussion in operetta reception and its conceptualization of an imperial identity. I do admit to being American, however.

Moriz Jung’s illustration for the operetta cabaret Fledermaus in Vienna, 1907.

You quote from Felix Salten’s review of the original Lustige Witwe. In that long article Mr. Salten speaks of Lehár’s music as making “carnal lust” audible, he also describes leading man Louis Treumann as a hysterical and effeminate modern man who is up-to-date. Again, this “carnal” side of operetta and the new male ideal are not discussed by you. Why? Or did I miss something?

Since you insist, I’m going to turn the question back on you for a second: I think you’re leveraging this aspect of operetta for a particular goal. That’s not to say that it isn’t there or isn’t important, but I think you are putting this weight on it in order to counteract a certain traditional image of operetta as frumpy, proper family entertainment, as I discuss in the final chapter of my book. By saying “but operetta was sexy and shocking!” you are claiming it for a counterculture or for modernity.

One of operetta history’s first (and most famous) “wet dream leading men”: Louis Treumann as Danilo, 1905.

I think this has traditionally been overemphasized by the intelligentsia of operetta, because, bluntly, they assume grandma entertainment (or, to use a more academic term, Marcuse’s affirmative culture) is less worthy of study or is less congruent with their own identities. Whether operetta is an art of the outsider or the insider is actually one of the central questions of my book! To be fair, the less sexy historical traditions also have a number of political connotations as well, so I can see legitimate reasons to efface it. But as a historical project, I am a little skeptical.

“Die neuesten Noten des Herrn Jacques Offenbach,” i.e. the latest compositions from Mr. Jacques Offenbach. From: Kikeriki, 1865.

In this book I wanted to reckon, in short, with romance (one very influential book for me Janice Radway’s quite old but still important study Reading the Romance). 20th cenutry operetta plots provide a kind of closure and dream fulfillment from a particularly female perspective. It’s the women in operetta who are more likely to be socially mobile and they get a kind of subjectivity and independence they aren’t often granted in the realm of fin-de-siècle opera. This is the heart of my Chapter 2, on Eva and Ein Walzertraum, both of which are operettas which center the idea of romantic fulfillment in a way that 20th century opera, in all its luridness, generally does not. (I would also like to note that the history of operetta has been written almost entirely by men.)

Sheet music cover for Oscar Straus’ “Ein Walzertraum.”

You use the terminology Gold and Silver operetta throughout, you even point out when it was first introduced in 1947. But you don’t ask why this choice of terminology by two Austrian authors might be seen as problematic and anti-Semitic. They basically substituted the Nazi categories “Aryan” (19th century) and “degenerate” (20th century) operetta with gold and silver. Was it a conscious decision on your part to not ask too many questions about the complicated political history of German language operetta post-1933 and especially post-1945?

I do discuss this debate over terminology in some detail in my book and I use “Silver Age” with scare quotes to indicate a degree of distance. But the idea of this periodization considerably predates the Third Reich; as my chapter on Die lustige Witwe argues the idea of a generational shift in operetta was being theorized even before the premiere of that operetta. Critics were desperate for a new generation of composers and tried to make Heuberger and, most prominently, Leo Fall’s Der Rebell into that moment. Unfortunately Fall didn’t work out, like, in the least, which is an interesting illustration of how, to quote Mean Girls, critics always want the Offenbach revival to happen but audiences insist that it’s never going to happen. (For an interview with Laurence Senelick about Offenbach, click here.)

The cast of the tv series “Mean Girls.” (Photo: Paramount Pictures)

Of course there are other ways to divide things up—you can argue for Zigeunerbaron as a turning point, or for Opernball. But you can find the 19th/20th century periodization in lots of pre-war sources and nascent in things like Erich Urban. I don’t think we can give the Third Reich credit for inventing the idea that 19th and 20th century operettas were very different things. (Read more about this topic here.)

What are the new aspects you present in your book? Things that have not been covered by previous authors? Which points are especially important to you? What surprised you in your research?

Operetta research in German is largely the realm of Theaterwissenschaft rather than Musikwissenschaft, and I’m trained as a musicologist. I use those languages carefully because the methods of Anglophone musicology are different from German theater studies or musicology. I’ve learned a lot from those other fields and don’t claim that my field is better, but I do think looking at things from a different disciplinary perspective can tell us different things. I tend to write more about the musical scores, I’m interested in how operetta is related to opera (particularly as someone who has also done research on both Richard Strauss and Puccini), and this discussion of middlebrow culture I mentioned earlier is something that has been traditionally quite Anglophone in orientation. I think it can bring something interesting to Germanic material as well.

I think the ubiquity of operetta as music in its time is something that we still often ignore. It’s mentioned quite scholars of people like Schoenberg or Kraus but always as a kind of boogeyman, as the music those lone wolves were working against. I’m interested in what this enormously popular genre was saying to people.

In your final chapter you compare a more “traditional” approach to operetta with a “contemporary” performance style. Who are the fans of either – and do you see any contemporary operetta performances in the USA?

I don’t want to generalize about people who go to the theater, especially because I feel like it’s been way too long since I’ve stepped inside of one. The vast majority of people go to what is most readily available to them and it’s only the fanatics like you and me who argue about such things. But the theatrical culture of operetta is indeed unique. That chapter was written, essentially, for those who aren’t familiar with these theatrical systems: those who encounter operetta productions on video or as tourists and don’t quite understand what’s going on and would benefit from a brief introduction to some of the main theatrical lineages in operetta production and discussion of some classic examples (some of which they can see on DVD). That chapter—and the whole book—ends with a discussion of Claus Guth’s Oper Frankfurt production of Die lustige Witwe, which is probably my favorite of all the contemporary productions, but unfortunately isn’t on video. I write all of this from the perspective of a music critic, not a programmer or producer. (For a CD review of the Frankfurt performance, click here.)

These works don’t have the kinds of histories in the US that the do in Europe so a production here, to work for an American audience, would look very different. The US’s highly developed Broadway musical performance tradition means we have lots of great performers who I think would be terrific in operetta roles, but there isn’t a clear place in the American theater world for operetta to exist. When it pops up, it’s usually at summer festivals or schools or a few specialist theaters. I had the opportunity to program a revue-type performance at the Bard Music Festival a few years ago, which was fabulous (the theme was European operetta about America), but those chances are few and far between.

You single out productions by Barrie Kosky in Berlin. Are Americans aware of what is happening in terms of an operetta revolution in Berlin? (The New York Times occasionally reports.) Is there any chance, in your opinion, that such a revolution might also sweep the United States? Is your book an incentive to re-think the genre and perform it in new ways?

I know, I wrote some of those New York Times reports myself. Kosky’s style is definitely the most visible current operetta practice to American scholars (I never see other Americans in Baden bei Wien!). Sometimes when I go to the Komische Oper in the summer it feels like a meeting of the American Musicological Society. But that’s a very, very select group; it’s not the same as the people I see at Fun Home at my local professional theater here in Fayetteville. If you get an operetta here it’s probably Fledermaus (we had it here a few summers ago, actually), and basically it is produced like an opera.

I don’t think transplanting European works to the US would work if that’s what you mean. The Kosky approach works because it draws on a whole range of cultural codes which are legible and funny to his audience. An American equivalent would have a different vocabulary and sense of humor, which Europeans would probably find alienating. But I think American efforts at this work has, understandably, largely concentrated on American musical theater works. I think you can see the recent Broadway revival of Oklahoma! (the “sexy Oklahoma!”) as a kind of reinvention akin to Kosky, though that musical itself is a more established text.

Research into Popular Musical Theater has been busy with a lot of re-framing in recent years: feminism, racism, colonialism, gender and sexuality etc. have all been big topics. You hardly discuss any of them. Is operetta, as a genre, not part of such current debates? Or is it a safe space where one is blissfully untroubled by the controversies of the modern world?

Overall, I must disagree, because my Chapter 3 is largely about gender and Chapter 5 is about exoticism. But I do discuss these things as a musicologist, not a theater studies person, so the methods look different from what you see in a lot of writing about operetta. In musicology there is always a concern that you are ignoring “the music itself,” and while I like reading about all kinds of operetta that sort of thinking still shapes my approach. So when I write about race in operetta I have tended to focus on how racial Others are represented musically, as in my analyses of Rose von Stambul, Die Bajadere, and Das Land des Lächelns. And I found working on those pieces quite interesting because despite having a very standard vocabulary of musical exoticism that constructs a dichotomy of self and other, twentieth-century operetta tends to then undercut or subvert notions of racial difference.

“Bajadere” 1929 at the Johann Strauß Theater in Vienna, with Walter Jankuhn and Annie Ahlers. (Photo: Operetta Research Center)

Also, I do want to note that you need to be very careful when talking about colonialism when dealing with Austria-Hungary because its overseas colonies were very few. Rather, it was a multinational European empire, which is itself very interesting and as indicated by my title the primary focus of my book.

That being said, I hope to be publishing an article about operetta and the women’s movement—I’ve been working on Lehár’s Die Juxheirat—sometime soon!

You discuss a great many shows in your book by various composers. Is it possible to listen to them in recordings that you’d describe as “adequate” or even “good”? How would be characterize the situation of operetta on record today?

“Good” is in the ear of the beholder because there’s no general consensus as to what operetta should sound like. There’s certainly an operetta crowd that thinks the bigger the orchestra and the more Wagnerian the singers, the better, and that’s how you get most of those recordings on cpo. And maybe that’s true for a few operettas, like Zigeunerliebe or Schön ist die Welt. But it’s not what these scores sounded like at the time.

Two big tenors, Piotr Beczala and Jonas Kaufmann, have released operetta CDs in the last few years and I was initially excited about them because I think they’re both great singers. But both were very disappointing, alternately stodgy and lugubrious and self-serious and just not fun. I concluded that most major record labels (and perhaps tenors and conductors) don’t really know how to perform or record something that has an orchestra but isn’t Wagner or Mozart. There’s a long tradition of opera singers approaching this repertoire, but some of it works better than others. For a positive example, I think Barbara Bonney’s operetta CD is gorgeous, she finds a way to make the music work for her quite wonderfully. It’s just voice and piano and she can be so intimate and direct, never appearing to overdo it.

I think the best way to experience operetta is in a theater, really. Hopefully you’ll get dancing, you’ll get a spontaneous audience reaction, you get storytelling, even if there are elements of the performance practice you disagree with there’s still a lot else going on. When you’re listening to a recording, the failings become more central. (A reviews of the original Lustige Witwe interpreters from Vienna 1905 and Berlin 1907, newly released on CD by Truesound Tranfers, can be found here.)

What about YouTube: it offers a chance to hear many historic performers. What is the most notable difference in performance style, for you? What could modern operetta performers learn from the past, what is “better” today?

Most modern performers who approach an operetta see themselves as performing a text, that is, interpreting a musical work that was written in the past and is attached to a certain tradition. That usually comes with expectations of fidelity (Werktreue) to whatever we know or, more often, assume about the composer’s intentions. Earlier performers of operettas, however, were more apt to see these scores as opportunities or starting points for performances, a distinction the musicologist Richard Taruskin refers to as “text and act.”

The performer who approaches their art as an act is more apt to be free with the material, to make it an expression of their sensibility, to make it work for the present moment rather than an imagined historical one. I discuss this in my book in the section where I analyze how Richard Traubner’s live performances coexisted with his recordings.

Operetta, however, was canonized pretty quickly and I think it has existed on the border between text and act for a long time. I would prefer a performance that is less precise, more individual, with more emphasis on words rather than legato. But Franz Lehár definitely wanted a “text” performance from the start. What he meant by that was lots more flexible than what we often get today, but the tension goes way back.

You teach at the University of Arkansas. How do your students and colleagues react, when you start talking about operetta? Does that put you in an avant-garde position, as being ahead of your time, or does it make you a pitiable nostalgic? (In their opinion.)

Most of my students have never heard operetta until I mention it or one of my voice faculty colleagues assign them something to sing. But I think they react very positively to it: it’s catchy, fun, accessible music, after all. It can actually be quite difficult for students to understand that operetta has often been looked down upon, because a lot of them haven’t inherited the idea of “selling out.” In general, I think this is positive and I like their egalitarianism, but sometimes I would also like them to more readily challenge themselves with work that isn’t so accessible. I love to teach Lulu too!

As for my faculty colleagues, well, it’s an obscure research niche like any other. We all have them. I had a colleague at a former job who was quite the snob and would ask me why I worked on trash. That’s a relic of an old-fashioned kind of musicology that believes music studies exist to prove classical music’s worth (usually with the revelatory conclusion that Beethoven was, in fact, a good composer), and as I already said that’s not my aim. But I think in academia we owe it to our colleagues to be generous and assume that the research they do is worthwhile, even if we don’t know much about it personally, and fortunately most of my colleagues have extended that to me.

In Germany, serious musicologists did not touch operetta for the longest time; it would have been career suicide, especially for young and aspiring academics. Has that changed, and what’s the situation like in the USA? (Are Operetta Studies a natural part of the Popular Musical Theater Studies, are you invited to the respective conferences etc.)

I’ve generally had a great reception to my research. Anglophone musicologists are vaguely aware that Viennese operetta exists but they don’t, for the most part, know all that much about it. I’ve been invited me to contribute to all sorts of projects and haven’t found much prejudice except from a few very old-fashioned scholars. I haven’t really been a part of the field of popular music studies, though; it tends to focus overwhelmingly on postwar material and doesn’t have a lot of space for theater music. I’ve found that my home is in opera studies because I’m interested in the theatrical work of operetta and many opera scholars are also considering the Austro-Hungarian nationalism and cultural issues that particularly interest me. My Doktormutter is a scholar of seventeenth-century Venetian opera, an opera industry with a business model not vastly different from Viennese operetta, and we’ve found a lot of methodological common ground.

As you’ve noted, there’s a lot still to be said about operetta. I hope there are lots more operetta scholars working in English soon!

You are very busy on Twitter as “Zerbinetta’s Blog.” What’s the status on operetta on Twitter and Social Media in general? Are there debates and shit storms about the genre? (Other than the fat shaming debate surrounding the Orpheus in the Underworld production at the Salzburg Festival….)

My Twitter list is mostly English-speaking and I haven’t seen much discussion of operetta, to be honest. I mostly use it as a social space and a way to discuss broader questions of teaching music. But when I see operetta come up I always need to join in! That Orphée discussion, by the way, seemed to have very little to do with operetta in particular and more about how we talk about, or don’t talk about, women’s bodies in general. It would be helpful and productive if we had more women writing music criticism and directing opera and operetta, just like I would like to see more women writing about operetta.

A girl after my own heart!!!!!

So glad to see this interview, and eager to have future opportunity to share ideas with Micaela Baranello and to read her book!