Alexandra Ivanoff (With Permission of the Author)

Sunday's Zaman (www.todayszaman.com)

28 December, 2014

In the music world, sometimes the concept of mixing vocal genres in the same performance works well, and sometimes it creates trouble. In July, I reviewed in Today’s Zaman two İstanbul concerts that dealt with this issue: One was a jazz saxophonist who suddenly burst into opera arias in the middle of his set, and the other was the estimable jazz singer Yıldız İbrahimova, who used her operatically trained voice to fashion superb “scat” artistry. In the saxophonist’s case, his sudden stylistic departure caused a disconnect; though his singing was remarkably good, it was a stylistic jolt for the audience. In İbrahimova’s case, she was the only one on stage in a large group and had the expertise to create an artistically satisfying experience. Combining vocal styles can be a tricky thing; the success or failure depends on several factors.

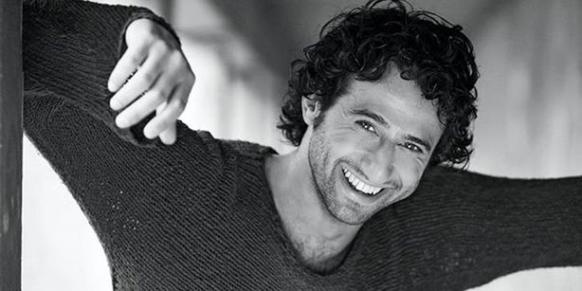

Turkish-German actor Serkan Kaya starred in Komische Oper Berlin’s “Arizona Lady.” (Photo: Sunday’s Zaman)

Two concerts in Berlin; one, a premiere of a rare work by operetta composer Emmerich Kalman and the other, opera singer Angela Denoke’s solo project of the songs of Kurt Weill, recently gave perfect examples of triumph and trouble, respectively.

Adding pop to operetta

The triumph was the Komische Oper’s Berlin debut of operetta composer Emmerich Kalman’s last opus, Arizona Lady on Dec. 21 [repeated on Dec. 30], for which director Barrie Kosky assigned two pop musical stars to join a cast of opera singers for a concert version of the work.

Serkan Kaya and Katharine Mehrling ready to go onstage in “Arizona Lady” 2014. (Photo: Katharine Mehrling)

The results were remarkable, not only because all the singer/actors involved were top-notch in their respective styles, but because Kosky allowed his performers full freedom to be themselves in a piece that essentially called for such a creative mixture – “a bouillabaisse from Kalman” remarked the director from the stage. Arizona Lady was written in 1953, but its score was a retro excursion through Viennese operetta, Vaudeville, 1920s Jazz Age, American musical theatre and other Americanisms — with an especially big tip of the hat to the “singing cowboy” phenomenon of the 1940s and 50s.

The performance featured Turkish/German actor Serkan Kaya as Cowboy Roy Dexter and Katherine Mehrling as Lona Farrell, the proprietress of the Sunshine Ranch in Arizona. Both are top stars of musical theatre in Germany.

Their splendid operatic colleagues were soprano Mirka Wagner, tenor Michael Pflumm, bass Jens Larsen, and buffo-baritone Stefan Sevenich. The polished five-man Lindenquintett Berlin as The Arizona Boys provided the mellifluous vocal convention established by the Comedian Harmonists in the 1930s, and the company’s expert chorus and orchestra, performing the premiere of Norbert Biermann’s lush orchestrations, were conducted by Kai Tietje (who also played accordion and harmonica from the podium).

Kaya, in a magnetic performance, sang with a remarkable blend of pop-rock fearlessness with touches of classical phrasing, matched by physical and emotional naturalness in his acting.

(The fact that Kaya is Turkish was used to good effect: he introduced himself as “Dexter from Kreuzberg” – the Turkish area of Berlin. Lona referred to him as her “Turkish cowboy;” and he later made a pun on the Mexican burrito “It’s ‘bör-ito,’ let’s get it right!”– referring to Turkish börek).

Mehrling, whose musical comedy chops are exemplary as a lead ingénue, tuned her emotive Broadway style vocalism, which included a yodeling sequence, to the perfect frequency for this elegant setting. Because these various performers were true to their own vocal realities and strengths, the concept of mixing genres — but especially informed by Kosky’s deft theatrical timing – was a resounding success. Following the show, Christoph Felsenstein, the son of the Komische Oper’s founder, announced to the crowd, “Ladies and Gentleman [because of Kosky's adventurous admixture of styles], the Komische Oper lives on!”

Denoke’s disaster

As I sat listening to international opera diva Angela Denoke’s evening of songs by Kurt Weill, entitled Two Lives to Live, at the smaller of the two Berlin Philharmonie halls on Dec. 1, I kept hearing Duke Ellington’s famous song lyrics “It Don’t Mean a Thing If It Ain’t Got That Swing.”

Poster for Angela Denoke’s Weill programm, designed by Honigtee Music.

Denoke has had an admirable career as a dramatic soprano singing most of the heroines in grand opera. Her decision to venture into musical territory, which required, to some extent, adding swing to her singing was, in my opinion, misguided.

“Swing” is musical delivery that has an organic rhythmic underpinning which grounds it so the performer can play with it in an improvisational spirit. That playfulness is the essential nuance that differentiates it from classical music. Not all of what Weill wrote required swing, or even a Broadway-style voice.

But her chosen companions that evening, pianist/accordionist Tai Balshai and saxophonist/clarinetist Norbert Nagel, thought so and they fashioned swinging arrangements perfect for a singer who could match them.

For those songs from Weill’s famous Threepenny Opera, The Rise and Fall of the City Mahogany, and Happy End, Denoke’s renditions were more or less a truer match to the music. But for pieces that required even a modicum of swing, like the snazzy duo arrangements with bass clarinet “Speak Low” and “September Song” and other up-tempo ballads, they lacked the required combination of backbone and looseness to be even moderately effective.

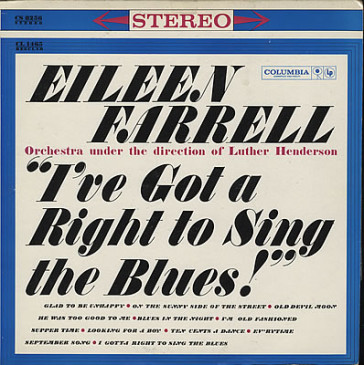

The cover for Eileen Farrell’s LP “I’ve Got A Right To Sing The Blues.”

Perhaps an even more serious issue was that Denoke had transposed almost all the songs to artificially lowered keys; this robbed her voice of its true colors and vitality, which normally bloom in a higher range than the one she was singing in. The results were pallid, boring and oddly inexpressive.

Throughout the evening, I was silently thinking of Eileen Farrell, the late great American opera diva, who made a controversial album in 1960 called I’ve Got A Right To Sing The Blues. She’s one of the very few who have successfully crossed over from classical singing to material that requires different expertise – one that makes blues and ballads believable – that thing called “Swing.”

To read the original version of this article, click here.