Kevin Clarke / Translated by Robert L. Folstein

Offenbach Society Newsletter

December 2019

No one can really claim that there is not an abundance of exciting Offenbach literature that has been published since the composer’s 150th birthday in 1969, beginning with P. Walter Jacob’s thorough monograph Offenbach in Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten (Offenbach in Autobiographical Writings and Pictorial Documents). But we can note that the perspective on Offenbach has widened noticeably in recent years and that many new topics have come into sharper focus, at least in German language research circles.

Jacques Offenbach photographed by Nadar in the 1860s.

There was the revolutionary publication in 1999 of Offenbach und die Schauplätze seines Musiktheaters (Offenbach and the Venues of his Music Theater) edited by Rainer Franke. It contains essays such as “Offenbach and the French operetta as reflected in the contemporary Viennese press,” and “Offenbach in London: a chronology of performances since 1857.” There is also Manuela Jahrmärker’s marvelous “Vom Sittenverderber zum ewig klassischen Komponisten” (From Corrupter of Morality to Eternally Classic Composer”). This collection of essays includes so many historical sources (newspaper articles, etc.) that it is a revelation to read just how the composer’s contemporaries judged Offenbach’s musical theater, with “corrupter of morality” being the most restrained of many outraged verdicts.

The cover of “Offenbach und die Schauplätze seines Musiktheaters.”

Just a year later, the monumental biography by Jean-Claude Yon appeared in France under the simple title “Jacques Offenbach.” Yon also quotes extensively from historic newspaper articles, however, he focuses mainly on French sources while the authors in Franke’s collection primarily use German-language sources. Yon’s work is also a treasure trove of information that earlier authors had avoided, presumably because it was deemed unfit for an “eternally classic composer”. Yon left no stone unturned and, for the first time opens Offenbach’s private life with documents—including birth certificates—that allow us to look at material that has been swept under the rug for a long time. For example, he gives us a more detailed look at his liaisons with his lead singer Zulma Bouffar and the existence of his illegitimate children. (Bouffar created the role of Gabrielle in La Vie Parisienne.)

Zulma Bouffar photographed by André Disdéri in 1866.

Later, there was a splendid Offenbach exhibition at the Orsay Museum, along with a wonderfully illustrated catalog. Offenbach also appeared prominently in a 2012 exhibition at the Theatermuseum Wien in a section headlined Die Geburt der Operette aus dem Geist der Pornografie (The Birth of Operetta from the Spirit of Pornography)—the same title can also be found in the catalogue Welt der Operette (World of Operetta). Already in 1937, Siegfried Krakauer in his book Offenbach and the Paris of his Time had a lot to say about the erotic dimension of Offenbach’s theatrical works. In 2014, libretto researcher Albert Gier addressed this topic too in his book Wär’ es auch nichts als ein Augenblick: Poetik und Dramaturgie der komischen Operette (Even if it were nothing but a brief moment: poetics and dramaturgy in comic operetta).

The cover of Albert Gier’s new operetta study.

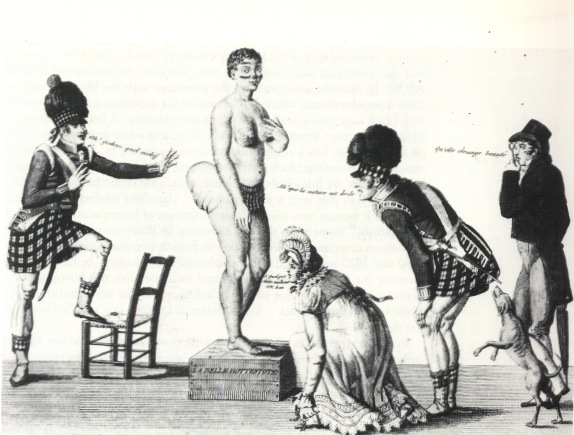

And in 2015, Bonnie Gordon of the University of Virginia provided seminal reflections on the Offenbach divas, early forms of feminism, racism at the Paris World’s Fairs compared to “exhibiting sexual savages” on the Offenbach stage. Gordon takes her cue from Émile Zola’s novel Nana and discusses Nana-playing-Venus as opposed to Helena-the-blonde-daughter-of-Venus and Sara Baartman, the “Black Venus”, moving on to Hortense Schneider and Cora Pearl as “sexual savages” being “exhibited” on the operetta stage (both were legendary Offenbach interpreters and demi-monde goddesses). Gordon closes by asking how we, today, deal with such “racism” and “colonialism”, not to mention “anti-feminism” which others have recently interpreted as acts of “liberation” and “emancipation”.

19th century French print “La Belle Hottentot” of Sara Baartman.

Which leads right up to the year 2019 and the many new books that have been published to celebrate the bicentenary, most of them in German, with one notable exception: Laurence Senelick’s Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture is undoubtedly a revolutionary and very up-to-date English language study of Offenbach, published by Cambridge University Press and released at quite an exorbitant price. (A paperback edition is in the making, luckily!) The book is a definite must-have: because Senelick traces exactly how and why Offenbach’s “morally shocking and corrupting” works made such impact globally. His book is not really a biography, but, rather, the story of the world-wide success the composer had with a very particular and unique kind of commercial musical theater, starting back during Offenbach’s lifetime and continuing up to the recent past. The pictures from performances in Japan, the Soviet Union, and the United States are breathtaking.

“Jacues Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture” (2018) by Laurence Senelick, together with the ground breaking “Offenbach und die Schauplätze seines Musiktheaters” (1999).

In his analysis, Senelick acknowledges and has taken note of the many new perspectives used in the study of Offenbach and the genre operetta: from gender studies to post-colonial/racism debates and LGBTIQ considerations, just about everything I personally ever wanted to know about is in there. I devoured the book and never regretted the price.

President Grant and Jim Fisk watch “La Périchole” at the Fifth Avenue Theater in New York, 1869. As shown in the “Illustrated Police Gazette.” (From: Laurence Senelick, “Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture,” 2018)

I can not make quite the same claim for Ralf-Olivier Schwarz’s book Jacques Offenbach: Ein europäisches Porträt (Jacques Offenbach: a European Portrait). It traces Offenbach’s development in a decidedly classical manner: from Cologne to Paris, then back and forth between Vienna and Bad Ems. Apart from some nice (and not well known) quotations from Offenbach’s private correspondence to his siblings and colleagues, there is little in the book that was not covered by P. Walter Jacob in 1969. The older book also has the more interesting illustrations.

Ralf-Olivier Schwarz’ “Jacques Offenbach. Ein europäisches Porträt.” (Böhlau Verlag, 2018)

What Schwarz does give us are detailed synopses of many works, so you always know what is happening in the ones he talks about. But what makes these works special—and why they gained such appreciation in the highest social circles in Europe despite their sometimes simple musical structure and outrageous stories—are subjects that Schwarz does not discuss. For him they are (almost) all ingenious compositions; he apparently believes that this is all you really need to know and he has no interest in going beyond that. (Some works, such as Daphnis et Chloé, are even evaluated by Schwarz as “untypical” Offenbach works without particular musical value because they are supposedly lacking Offenbach’s typical parodist style; something you could hotly debate.)

Famous Austrian playwrite Johannes Nestroy as God Pan in Offenbach’s “Daphnis und Chloe” in Vienna. (From: Laurence Senelick, “Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture,” 2018)

Mr. Schwarz quotes rather extensively from Zola’s Nana, particularly the chapter that describes the operetta performance of “The Blonde Venus” at the Théâtre des Variétés. As you will recall, this is the stage that produced the great Offenbachian hits La Belle Hélène and La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein, both featuring Hortense Schneider in the title roles; the house where the Prince of Wales visits La Snédèr in her dressing room. Zola goes into a great deal of detail here and leaves little to the imagination. But Schwarz stops short of quoting what Zola describes as Nana’s major impact: namely her brazen naked appearance, which drives the men in the audience wild and “opens an abyss of unknown desire before them”.

In his novel “Nana”, Emile Zola describes a “Belle Hélène” performance that is only slightly veiled as “The Blonde Venus”. Zola makes it very clear why the original diva attracted such attention, and caused such a sensation.

There are existing historic sources (quoted in Franke’s book) which prove that Zola was not just fantasizing freely when he wrote about nude divas and theaters as brothels, in the Penguin Classics edition of Nana we learn that it was, in fact, Ludovic Haley who took Zola backstage and gave him all the glorious details in person. Schwarz leaves all of this out. While Laurence Senelick published extensively about it in his 2018 essay Sexuality and Gender in the series The Cultural History of Theater in the Age of Empire: discussing the “white slave” contracts actresses had to sign obliging them to sleep with visitors, the display of bodies (male and female), prostitution in theaters, and the impact of all these externalities on theatrical musical entertainment, including the works of Offenbach.

“The Dressing Room of Hortense Schneider,” 1873. Painting by Edmond Morin.

In Schwarz’s book, on the other hand, Offenbach is presented as a loving, nice family-father who, admittedly, likes to go on trips without his wife. But his infidelities are of no concern when it comes to judging his importance as a composer. Schwarz also does not mention the findings of Carolyn Williams regarding the parody concept of early operetta, and the modernity of the re-sampling and re-cycling process of “older” music in order to ridicule it. That this technique makes Offenbach really unique and way ahead of his times, that the blatant sexuality of his works guaranteed their success, that Offenbach’s divas got exorbitant fees in the USA, paid in gold (noted by Mr. Senelick) are all topics that Schwarz has nothing to say about.

Instead, he quotes extensively from Offenbach , mon grandpère, the 1940s reminiscences by Offenbach’s grandson Jacques Brindejont-Offenbach. And he does this without ever questioning the reliability of the descriptions of a harmonic bourgeois family life that the author knew about through hearsay at best. Needless to say, family memories of a grandson can never be considered a reliable source, especially after Yon has proven otherwise: this does not mean that Offenbach was not a good family man, but that he knew that he had to keep his life divided into several spheres which he kept completely separate. And this separation is not insignificant in considering his career so, therefore, important when describing his oeuvre.

Queen Esther, a painting by Edwin Long (1879) from the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Mr. Schwarz is an expert/consultant to those involved in the extensive celebrations of the composer’s 200th birthday in Germany. They consist of many performances in Cologne of rare and believed lost pieces by Offenbach and his family, including the singspiel Esther, Königin von Persien (Esther, Queen of Persia) by his father Isaac. That is wonderful and very, very exciting. But it does not change the fact that I personally found Mr. Schwarz’s biography to be too non-controversial, at least in the sense of omitting everything that could somehow be considered “provocative.”

Emily Soldene as Offenbach’s Helena.

But Offenbach’s musical theater was a provocation to his contemporaries. Patrick O’Connor, among others, has written extensively about it in the Opera Rara insert for their recording of Vert-Vert. He documents that Offenbach’s attempts at the Opéra-Comique failed mainly because the general public was concerned about the reputations and chances for marriage of their daughters if they were to be seen at an Offenbach performance. The same observation was also described by Offenbach diva Emily Soldene in My Theatrical and Musical Recollections regarding the appearances of Hortense Schneider in London as The Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein in 1870/71. The theater was half empty because the general public was mortified by Schneider’s “suggestive” hip-swinging performance as the “lusty lady” and feared “hurting the modesty of their wives and daughters”, while the aristocracy and high-aristocracy sat in the expensive boxes and applauded. They simply did not care what the rest of the world thought of them; they could afford to be immoral.

Kurt Gänzl’s edition of Emily Soldene’s memoires.

Information regarding Offenbach’s political relationships and activities also remain vague in the Schwarz book. For that topic, a new book by Alan Strauss-Schom is more informative; it is a biography of Napoleon III. Under the title The Shadow Emperor one learns much about the world of the Second Empire and the people who sponsored Offenbach, especially Napoleon’s half-brother, the Count de Morny. I was captivated by the facts that Strauss-Schom develops for Morny, because they make clear how Offenbach—under Morny’s protection—managed to get his theatrical antics through the official censors and why Morny’s friends from the Jockey Club and the imperial family supported Offenbach’s theater. Years ago, director Istvan Szabo—in the film Offenbach’s Secret—had already shown that Morny was the actual person behind all the political allusions and jokes in Offenbach. After reading Strauss-Schom, that seems absolutely plausible to me. Ralf-Olivier Schwarz hardly mentions Morny; he does not even think that the count being the godfather of Offenbach’s only son is highly unusual – and special. By the way, the Strauss-Schom book contains an independent Offenbach chapter.

If you are looking for more detailed information about unfamiliar works, you can also find them in Heiko Schon’s new book, Jacques Offenbach – Meister des Vergnügens (Jacques Offenbach – Master of Pleasure), including some interesting references to recordings old and new. But: it’s in German.

Book cover “Jacques Offenbach – Meister des Vergnügens” by Heiko Schon. (Photo: Regionalia Verlag)

One could say that the final word regarding Offenbach and 2019 has not yet been spoken. I am anxious to discover what other books are yet to be released, especially in English. (It seems the English speaking world is somewhat behind in terms of operetta research, compared with Germany and Austria; but that might change with various new operetta companions in the making at Cambridge University Press and Routledge.)

Ngako Keuni in “Dream Girls” style at the UdK production of “Die schöne Helena,” 2018. (Photo: Madis Nurms)

After recently seeing a performance of La Belle Hélène by a group of Berlin musical students at the UdK, I took Bonnie Gordon off the shelf and read it again, wondering whether or not the EMI recording of La Belle Hélène with the late Jessye Norman is “racist”. There, one thing leads to another and is put in context with other themes. In the end everything leads to topics that are now being hotly debated all over the world in times of #metoo, #timesup et al. And it’s worth examining Offenbach and operettas in exactly this context. By the way, Bonnie Gordon’s essay is in English, even if the book Kunst der Oberfläche: Operette zwischen Bravour und Banalität edited by Clemens and Bettina Risi is (mostly) in German. It would benefit from an all-round English edition, as would the Yon biography, which no one has translated yet, not even for the bicentenary. Which is truly shocking!

I wonder how much it would cost to have the Yon book translated. I think the cost could be raised.