Alan Lareau / University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh

Monatshefte, Vol. 109

No. 3, 2017

Over the past twenty years, German-speaking operetta has been enjoying a revival, especially Berlin operettas of the Weimar Republic by figures such as Paul Abraham, Oscar Straus, and Ralph Benatzky. Stages like the Komische Oper in Berlin have been rediscovering forgotten works and reinterpreting classics to expose their youthful, anarchic, and often queer sensibilities. The sensational opening salvo for this new wave of operetta productions was a 1994 production of Benatzky’s war-horse Im weißen Rössl in Berlin’s intimate cabaret Bar jeder Vernunft, starring cult figures of the sub-cultural scene such as the Geschwister Pfister alongside mainstream actors like Otto Sander and the popular bandleader Max Raabe.

Until then, this work was remembered primarily for the corny 1960 film adaptation starring Peter Alexander, and the title long evoked scorn for its alleged sentimentality and kitsch – an accusation the Nazis had already made against it. New interpretations, both on stage and on the printed page, reveal that there is much more to the operetta, and that it may indeed be viewed as a key work of Berlin’s popular culture between the wars.

Modern scholars champion Im weißen Rössl as an impudent, parodic send-up of genres, clichés, and identities; indeed, the irony and satire in the work were, as we now are given to understand, at the core of its 1930 premiere production at the hands of the gay director and dancer Erik Charell in Berlin’s Großes Schauspielhaus, where it was mounted as a hilariously over-the-top revue spectacle, playing more than 400 performances to a house of 3500 viewers.

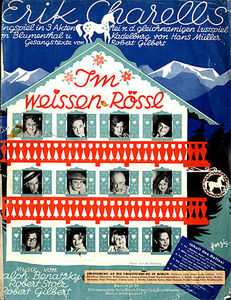

Sheet music cover for “Im weißen Rössl” 1930.

It then went around the world, including to London and New York (as The White Horse Inn), and also reappeared in a host of adaptations and parodies; most recently, it was modernized in the campy film comedy Im weißen Rössl – Wehe, du singst! of 2013.

That this is the third book devoted to this operetta to appear in just over ten years (following Ulrich Tadday, ed., 2006, and Helmut Peter/Kevin Clarke, 2007) attests to the work’s growing status beyond mere cult fandom.

Derived from a hit comedy of 1898 by Oskar Blumenthal and Gustav Kadelburg, Im weißen Rössl revolves around the urban and rural character types at an Austrian tourist hotel and their misplaced love interests.

Many of the songs, with clever lyrics by Robert Gilbert, became evergreens (“Was kann der Sigismund dafür, dass er so schön ist” and others).

The newest impetus for reassessment is the 2008 rediscovery of the original orchestral arrangements thought lost during World War Two. They attest to the witty, jazzy character of the 1930 score, which was obscured by the more conventional, homogenizing orchestration that has been in circulation since 1951.

This archaeological revelation launches the volume of essays under review here that grew out of a 2015 symposium in St.Wolfgang, bringing together historians from music, literature, theater, and media studies to again cast light on the work, its genesis, and its reception.

As editors Nils Grosch and Carolin Stahrenberg observe in their opening portrait, a new era of research and productions has begun.

Nils Grosch und Carolin Stahrenberg’s “Im weißen Rössl. Kulturgeschichtliche Perspektiven.” (2016)

The far-ranging critical essays are therefore interspersed with short highlights from artists involved in novel contemporary productions. The initial studies reveal the complexities of authorship in popular culture, such as the previously overlooked but crucial role of the musical arranger Eduard Künneke, himself a composer of note, who emerges here as a co-creator hidden in anonymity.

Wolfgang Jansen and Fréderic Döhl examine the arguably underestimated roles of the librettist Hans Müller and the producer-director Erik Charell respectively; Nicole Haitzinger emphasizes the central (though difficult-to-document) function of choreography in the work, while others draw attention to the supporting composers, above all Robert Stolz, and the changing incarnations of the production as it relocated to other cultures, such as Jimmy Berg’s émigré parodies in New York.

Advertisment for “White Horse Inn” from “Aufbau,” December 1947.

Grosch, in an essay of his own, similarly exposes the ambiguities of genre revealed here, tracing how the work oscillates between Singspiel, operetta, revue, and musical.

Subsequent contributions move from the historical to the interpretational, looking into the Jewish dimensions of the operetta (noting its largely Jewish authorship), its humorous techniques, its uses of the theme of tourism, and its multimedia interactions. Above all, it is the ironic and self-reflective power found throughout the text, music, and staging – long overlooked but now rediscovered – that offer the potential to raise Im weißen Rössl beyond the trivial to the ranks of a masterpiece.

Ernst Stern’s fantasy costumes for the girl dancers in the Broadway production of “White Horse Inn.”

Though the volume’s restriction to one work gives it a tighter focus than most such conference collections, it does not attempt a cohesive and systematic overview, and some of the later chapters go somewhat afield. A good introduction establishing the previous scholarly groundwork would have been helpful for outsiders coming to the work for the first time, and a solid critical review of the screen adaptations (of which there are four since 1935, plus a Danish version, a television film, and a silent film of the original comedy) from a cinema history standpoint is still sorely needed.

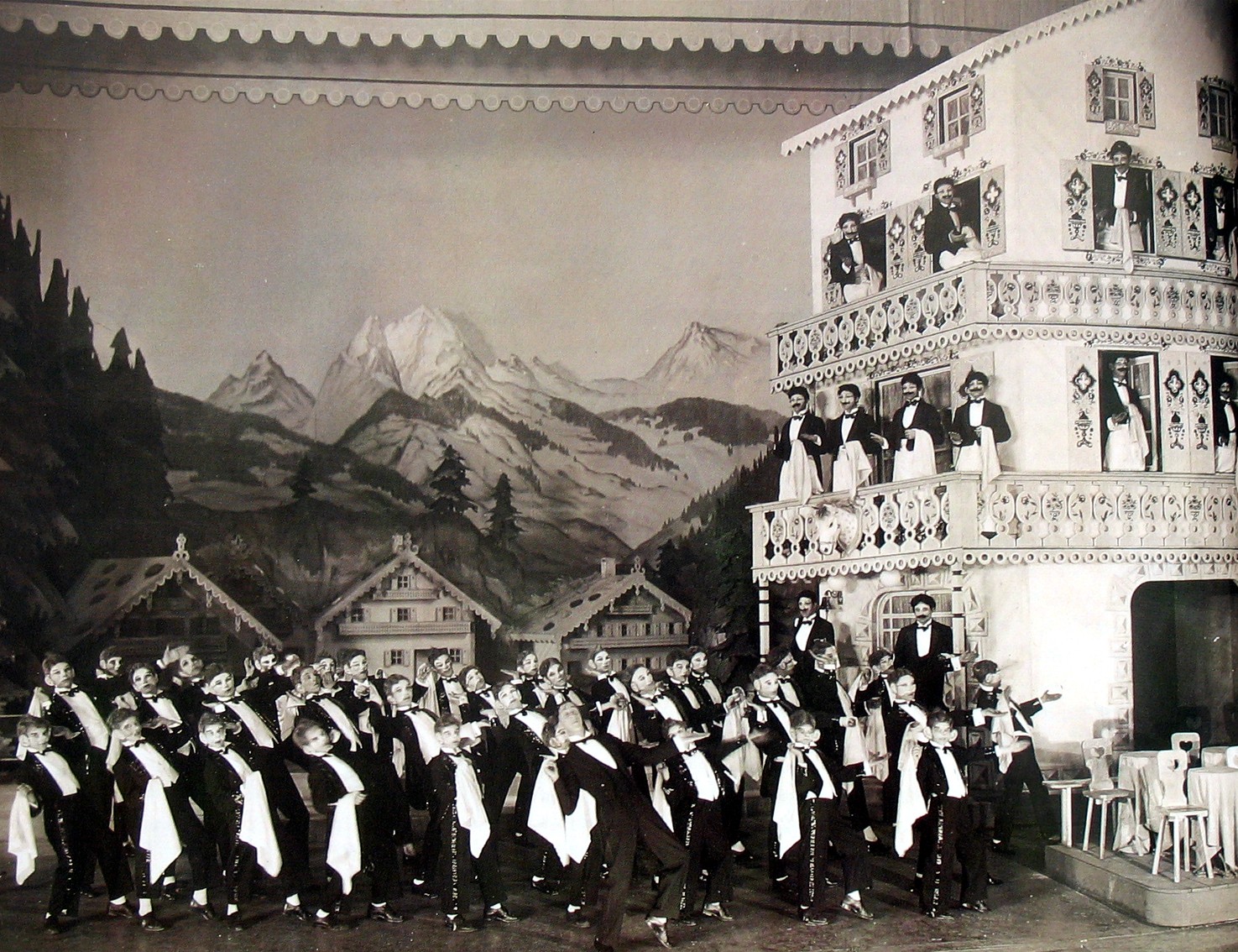

The collection benefits greatly from photos of old and new productions (many in color) and historical documents such as advertisements and costume designs, as well as a reprint of the complete original program booklet from Charell’s production.

Waiters on parade: the grand marching scene from London, 1931.

With the serious, engaging, and diverse studies gathered in this volume, Im weißen Rössl is clearly growing into a newly appreciated milestone of Weimar culture, promising fodder for yet another generation of stage and screen embodiments and scholarly investigations.