Kurt Gänzl

The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre

27 August, 2014

She was the six-year shooting star of Offenbach’s Théâtre des Variétés series whose dazzling career declined at the same time as that of the French Empire of which she was such a visible feature.

Hortense Schneider en „folie“, portrait by Alexis Pérignon.

Hortense Schneider, born in Bordeaux on 30 April 1833, made her first theatrical appearance in her native Bordeaux in the play Michel et Christine at the age of 15, and then moved on to play in Agen where she appeared in everything from farce to opera, as ingénue or pageboy or `amoureuse’. She was out of her teens by the time she got to Paris, where she soon got to know the comedian Berthelier and, with his help, auditioned for Hippolyte Cogniard (unsuccessfully) and for Offenbach, with whom Berthelier had scored a great hit a few weeks earlier in Les Deux Aveugles. Offenbach, at that stage still running his first little summer Bouffes-Parisiens house, was obviously more impressed by the pretty little actress than Cogniard had been, and she was given the female rôle, opposite her useful boyfriend, in the next Offenbach one-acter, Le Violoneux (31 August 1855).

Offenbach’s regular soprano, Marie Dalmont, created Ba-ta-clan later in the year, but the new little starlet, fresh from her personal success in the distinctly successful little rustic opérette, moved with Offenbach’s company to the new house in the Passage Choiseul and there created the more lively part of the actress of Tromb-al-ca-zar (1856, Simplette), appeared in Adam’s Les Pantins de Violette (reportedly to the delight of the composer), and triumphed in the delightful little three-cornered battle of La Rose de Saint-Flour (1856, Pierrette).

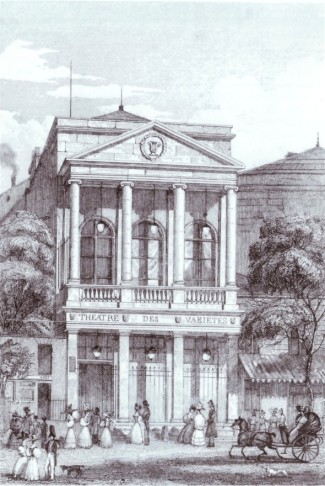

The Theatre des Varietes in Paris.

Cogniard now changed his mind about the young actress who was winning such delighted reviews for her charming performances and he whisked Hortense off to his Théâtre des Variétés where she opened a few weeks later in Le Chien de garde. From the Variétés she moved on to the Palais-Royal and over the next years, through a long series of the vaudevilles à couplets and other varied entertainments which made up the programmes of that house (Le Violoneux, La Poularde de Caux, Hervé’s Les Toréadors de Grenade etc), her reputation, both on-stage and off-, grew apace.

It was nearly a decade since her first appearance in Paris in Le Violoneux when Schneider, now something of a star, returned to Offenbach to create the title-rôle of La Belle Hélène at the Variétés (1864). The success of the piece, and of Hortense Schneider in the piece, were only equalled by those of its successors as the star followed up her burlesque Helen of Troy with the rough-and-tough but infinitely sexy last wife of Barbe-bleue (1866, Boulotte), as the pubescent teenaged Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein (1867) with her famous Sabre Song and her insinuating ‘Dites-lui’, and (in spite of difficult beginnings) the street-singer heroine of La Périchole (1868, Letter song).

This series filled the Variétés for the best part of four seasons and, during the off-season Hortense, at the height of her enormous fame, took her vehicles and ‘her’ company to other venues, notably across the channel to London, Dublin, Glasgow and other British centres.

There she appeared in her Variétés shows through several summers with great popularity and vast profit to her bank account. It was said that Raphaël Félix paid her £7,000 for 96 performances in Britain in 1869.

“The Dressing Room of Hortense Schneider,” 1873. Water color painting by Edmond Morin.

Always difficult, perpetually walking out and usually returning, avid over salary even though her royal and rich off-stage admirers made such cares unneccesary, Schneider became only more so as she became more successful. She was persuaded to appear as little more than her famous self in Offenbach’s La Diva (1869), but the piece turned out a failure and even her popularity could not save it. She turned down the rôle written for her in Les Brigands and left the Variétés, having created her last Offenbach rôle.

Several years later, after the Franco-Prussian War and after another truncated run – at a whopping 300 francs a night – last-minute replacing Augustine Dévéria in Hervé’s La Veuve du Malabar (1873, Tata-Lili), she agreed to return to the Variétés to appear in an enlargened version of her old rôle in La Périchole and again to play Margot, the titular baker’s wife in La Boulangère a des écus, the newest piece written by the authors of her greatest successes, but before the first night of this delicious new vehicle she had again walked out (or been dropped, depending which version you believe). Instead, she played Hervé’s La Belle Poule (1875, Poulette) with only mediocre results, and found herself on the end of several tart comments about playing her age.

José Dupuis and Hortense Schneider as Barbe-bleue and Boulotte. Caricature by Gill for “L’Éclipse,” 1866.

Schneider had no intention of playing her age. She had been the reigning queen of the Paris stage for a good half-dozen years, and she had no intention of now being its queen mother. She had seriously threatened, more even than just threatened, to quit the theatre before and she had no compunction about doing so now. With La Belle Poule the curtain came down on one of the most dazzling — if not extended – careers of the musical stage, and for the 45 years of life remaining to her, Hortense Schneider lived a life of respectability at utter odds with the gay and gallivanting years of her theatrical heyday when she had been known, not with a little admiration as ‘le passage des Princes’.

A character bearing little resemblance to Schneider but given her name and even a love affair with Offenbach was portrayed on the screen by Yvonne Printemps in the film Valse de Paris. A different romance for the composer – apparently with Empress Eugenie! – was proposed by the Hungarian author of the composer’s biomusical Offenbach (1920), but both real-life wife Herminie and Hortense appeared in the piece, the diva originally played by Juci Lábass. In the Vienna production she was portrayed by Olga Bartos-Trau, on Broadway by Odette Myrtil.

Hortense Schneider died in Paris, 5 May 1920.

Biography: Rouff, M & Casevitz, T: Hortense Schneider (Tallandier, Paeis, 1930), Bonami, J-P: Hortense Schneider, la Grande-Duchesse du Second Empire (Hérault, Paris, 1995)