Richard C. Norton

Operetta Research Center

30 August, 2015

You will recall that the Ohio Light Opera presented Lerner & Loewe’s Brigadoon as part of their 2015 summer season. Invited to give a lecture at their annual symposium was Richard C. Norton, biographer of Frederick Loewe. Mr. Norton has kindly allowed us the reprint his lecture here, for all those who didn’t make it to Wooster this year – and who love this romantic Scottish operetta.

Portrait of Friedrich Gerstäcker, 1870. (Photo: Wikipedia)

How many of you have ever heard of Germelshausen? It’s a short story written in German by Wilhelm Gerstacker in 1862. Here is a summary of its plot, as related by music theater historian Miles Kreuger: “A young artist, Arnold, is sketching woodland scenes, when he meets a pretty girl, Gertrud. He is struck by her beauty and curiously antiquated dress, and sketches her. She invites him to dine at home in the [nearby] village of Germelshausen, where she lives with her father, the local mayor, her step-mother and siblings. She has been waiting for her sweetheart, but is resigned to the fact that he will not come. During the meal there is singing and dancing by family members, all interrupted by the sight on the street outside of a somber funeral procession.

After lunch, Arnold and Gertrud stroll through the village with its ancient buildings and strangely dressed residents. They finally arrive at a cemetary where the girl begins to weep at the grave of her mother. When Arnold notices that the death date on the stone reads 1224, he questions Gertrud, who is evasive about this anomaly.

Attracted to each other, the couple return to her house to change clothing for a festive dance to be held that evening at the Inn. Though a stranger, Arnold is welcomed by all the young people. One man, sensing that Arnold might want to remain in the village, mentions cryptically that the intervals pass fast enough, a point of curiosity to the visitor.

There is much dancing and merriment, broken each time the town bell tolls the hour.

At eleven, Arnold begins to think longingly of his faraway mother and raises a glass to toast her. When Gertrud sees this, she realizes how much he misses his mother and escorts [Arnold] out of the inn, back to her home, where she hands him his traveling bag, and brings him to a nearby hilltop. She tells him to wait until the church bell strikes midnight and then come to the back door of the Inn, where she will be waiting to leave the village with him. She runs off toward the village and disappears in a dense fog that has suddenly risen.

As the bell tolls midnight, all sounds and lights from Germelshausen vaporize. Arnold walks to its former site but can find no trace of the village. He searches until the first light of dawn but to no avail. An old hunter appears and informs Arnold, who asks of Germelshausen, that according to legend such a village once stood centuries ago in that nearby swamp, but was cursed and sank beneath the earth, supposedly to reappear just one day every hundred years. Arnold slowly leaves, carrying his traveling sack with the sketch of Gertrud.”

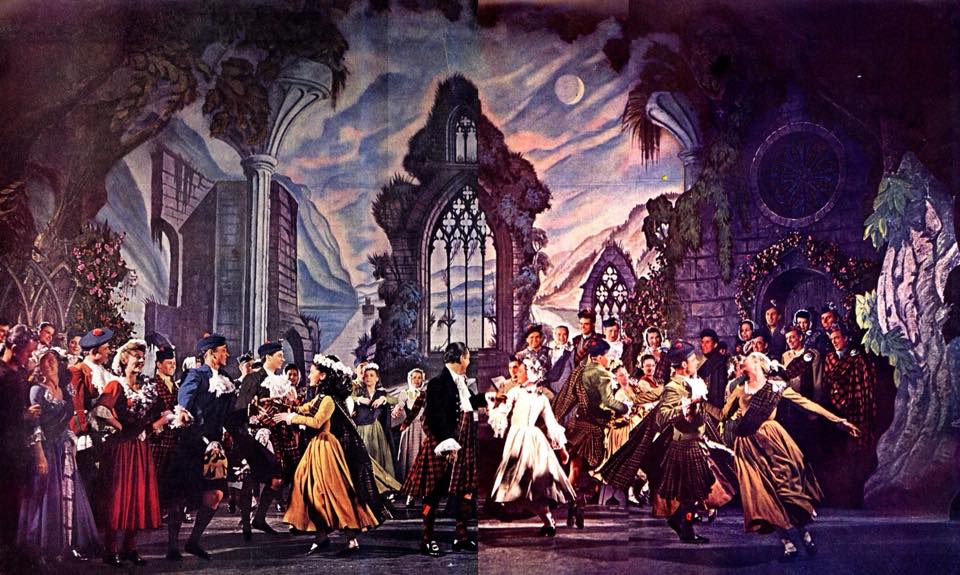

Scene in the Scottish Highlands from “Brigadoon.” (Photo: ORCA)

For those of you, many of you, who know Brigadoon, it’s plainly obvious where Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe found their inspiration for Brigadoon. Indeed Agnes deMille and Jean Dalrymple later recalled that Fritz Loewe intrigued Alan with the story, then obtained a copy of it in German, which he translated for Alan. Undoubtedly Fritz Loewe, like every German-born child of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, grew up knowing the short stories of Friedrich Wilhelm Gerstacker, in particular his Germelshausen. Gerstacker’s writings were immensely popular as light reading, not literature, because they extolled a simpler, pre-industrial, pre-Bismarck world the German public imagined as their romantic heritage. Its straightforward German prose was also available in American editions as a teaching instrument for basic German language instruction. When New York theatre critic George Jean Nathan pointed put the narrative similarities between Brigadoon and Germelshausen, Lerner denied it, and claimed his work was wholly original, or inspired by the fantasy of J M Barrie.

Be that as it may that the “Germelshausen” story was in the public domain, Lerner claimed in later interviews that he had tried without success to secure the rights to musicalize J. M. Barrie’s “The Little Minister”, before creating his own Scotch fantasy romance.

Lerner biographer Edward Jablonksi points out that the “Doon” is a river in southwest Scotland, which appears in the poetry of Robert Burns. And the word “brig” in Scots dialect means “bridge.” Hence Brigadoon sounds like the spot where a bridge crosses the Doon.

Nonetheless, let us credit the many smart changes Lerner made for musical theatre purposes. (1) The story was reset from Germany to Scotland, the dates changed from 1224 and 1864, to 1746 and 1946. (2) The hero Arnold becomes an American Tommy Albright, brash, optimistic, yet questioning. He’s accompanied by his cynical friend, Jeff Douglas. (3) The original story’s Gertrud becomes a Scottish lass Fiona. (4) It’s not the date on a tombstone, but the date inscribed in Fiona’s family Bible that first troubles Tommy. (5) Tommy learns the truth of Brigadoon, né Germelshausen, not afterwards from a chance encounter with a hunter, but during his stay in Brigadoon, from the dominie, or town schoolmaster, Mr. Lundie. (6) Lerner creates suspense for his narrative, with a moral choice for his hero: whether to choose for himself the materialistic life of a modern New Yorker with an ambitious wife, or return to a bucolic, some might say “fairy-tale” life, in old Scotland. (7) Lerner added a secondary romantic couple, Tommy’s best friend, Jeff Douglas (traditionally a non-singing role), and Meg Brockie, who sells milk and cream in MacConanchy Square. The aggressive Meg and reticent Jeff offered contrast and comic relief to the central romance, a story which some critics felt lacked humor. (8) Unlike Gerstacker, Lerner gives the story a happy ending. Lovers are reunited in a twist of plot at the finale.

Alan Jay Lerner expressed open admiration for Rodgers & Hammerstein’s musical plays, as they were called, Oklahoma! and Carousel. I ask you to think of Oklahoma! as a template or role model upon which Lerner based much of his libretto for Brigadoon. Just like Oklahoma’s Curley and Laurey with their duet “People Will Say We’re in Love” and Billy Bigelow and Julie Jordan’s “If I Loved You,” Brigadoon’s Tommy and Fiona express their feelings in a conditional love song, “Almost Like Being in Love.” When Brigadoon demanded comic relief, Lerner created secondary couple, the cynical (or oblivious) Jeff and the lusty Meg Brockie, patterned after Oklahoma’s Will Parker and Ado Annie. Indeed Ado Annie’s “I Cain’t Say No” is a blueprint for “My Mother’s Weddin’ Day” and “Love of My Life.”

The soubrette and male comic foil are not unique to “Oklahoma” by any means, but are staples of operetta and musical comedies of the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s.

All 3 musicals (Oklahoma, Carousel, Brigadoon) feature a death in Act 2, usually of an unhappy character who threatens the happiness of the principals.

In a real sense, for romantic musical theatre purposes, Lerner and Loewe “upped the stakes” for their hero, with an eleventh hour dramatic contrivance. They send him back from Scotland to a New York City bar in Act 2, Scene 4, to meet his pal Jeff, but more importantly Tommy’s estranged fiancée Jane. As she prattles on about this and that, Tommy’s mind and heart wander, her every word evoking the melodies, moments of the one day he shared with Fiona in Brigadoon. Lerner said he had wanted to write of a love and a faith powerful enough to move mountains. He sends a desperate Tommy back to the Scottish Highlands; it must have been a dream. Tommy cries out, “God! Why do people have to lose things to find out what they really mean?” As we soon learn, Tommy’s love is so strong, so powerful, he awakens Mr. Lundie, and returns to Brigadoon.

In a radio interview in the 1970s, Lerner spoke of how his musicals always demanded a “recognition scene” in which the hero has a catharsis or revelation. In Brigadoon, Tommy’s catharsis occurs in the musical scena of Act 2, Scene 4, in the Manhattan bar. More obvious examples from Lerner are Gaston’s discovery mid-lyric in the title song of Gigi that that little girl has become a grown woman before his very eyes. Or obviously, Higgins realization in My Fair Lady, “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face.” Camelot has two such recognition scenes for King Arthur, [not songs], his speech at the close of Act 1 when he confesses he’s powerless to stop the love between Lancelot and Guinevere both of whom he loves; and the close of Act 2, where he tells young Tom not to forget the legacy of the round table, but to spread its fame and story far and wide. Note that Lerner always gave his catharses to men, never to women.

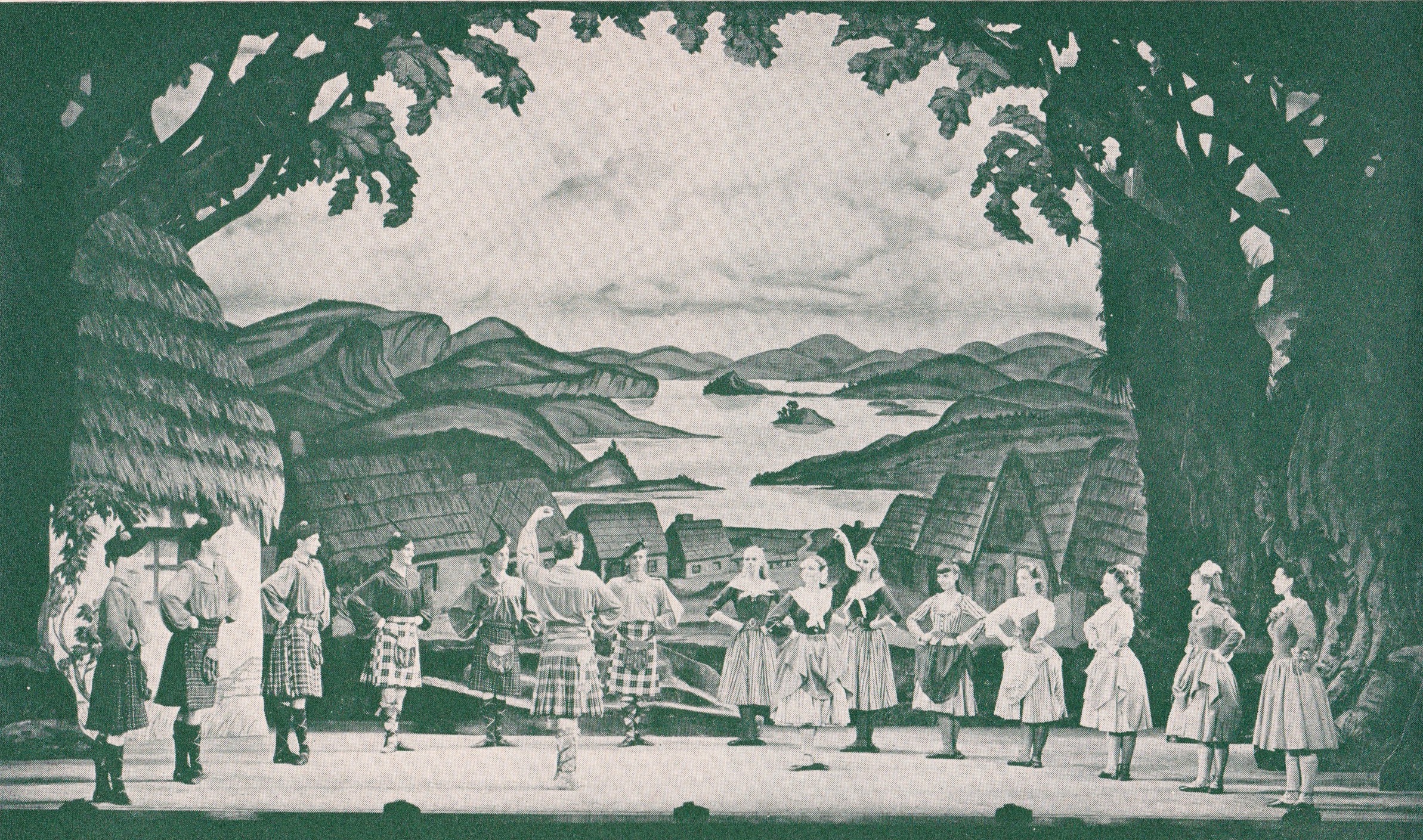

Indeed, Brigadoon was from its world premiere 6 February 1947 at the Shubert, New Haven, seemingly blessed. Although director Robert Lewis wasn’t even allowed time for a dress rehearsal, the production remained substantially unchanged for its New Haven, Boston and Philadelphia tryouts, gathering a clutch of rave reviews, word of mouth and a strong New York advance sale, all for a show with no stars. And to paraphrase the famous moniker from Billy Rose, who owned the Ziegfeld, and once said the same of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Oklahoma!, “No girls! No gags! No chance!”

Much as we all admire Lerner & Loewe’s brilliant dramaturgy, the truth is more complicated that it might seem at first.

Credit director Robert Lewis and choreographer Agnes deMille with the good sense, to make all their changes before rehearsals and tryouts began. According to Lewis’ theatrical memoir, Slings and Arrows, he and Agnes deMille conspired to make substantial changes in Lerner’s first draft, in their words, “How are we going to kill the Jeanette MacDonald in this thing?” They had a natural ally in scenic designer Oliver Smith, who got as far as the line where Tommy says “So you’re all perfectly happy living here in this little town?,” and the old dominie says “Of course, lad. After all, sunshine can peep through a small hole.” Smith called Lewis and said “I can’t go any further, because if I read any more, I won’t do the show.” Such hardened, cynical New Yorkers, tough theatre professionals! It’s precisely the collision between the modern world, its sterility, hardness as typified by Manhattan, and the lost world of the past, its guileless simplicity and kindness, as embodied by Brigadoon, that Tommy must choose.

Scene from the original “Brigadoon” production on Broadway. (Photo: Richard C. Norton Archive)

In Lerner’s own memoir The Street Where I Live, he writes: “When Cheryl Crawford sent Bobby Lewis the script with the hope that he would direct it, Bobby came to see me and asked me what I thought I’d written. I was startled. It was the first time anyone had asked me that. I said, rather glibly, that I had written a fantasy about a town in Scotland that returns to life one day every one hundred years. ‘No,’ said Bobby, ‘that’s not what you have written at all. What you have written is the story of a romantic who is searching, and a cynic who has given up… In the end cynicism is proven wrong.’ The moment he said it, I realized he was right. And after having struggled with the imperfections in the script for many months, I was able to complete the final draft within a week.” What Alan as the writer recounted was the story of the play. As a director, I was searching for the theme.”

Think back to 1947, two years after the end of World War II; America’s cultural and military imperialism, its “can-do optimism” was in ascendance.

L&L’s romantic fable is a cautionary tale, a glimpse back into a vanished world, re-captured for one brief shining moment. Metaphorically, think of Brigadoon as a symbol of old Europe, its villages and castles destroyed by two world wars, and America as the embodiment of a new world order, its gleaming skyscrapers and skyline Tommy sees in Act 2, Scene 4. Now choose!!

Several critics have observed that Alan Jay Lerner often writes about himself as the protagonist in his musicals. He is very much like Tommy Albright, the hardened New Yorker who discovers his own romantic side in Brigadoon. Lerner is also very much like Higgins in My Fair Lady, the aloof, well-educated misogynist who creates his own ideal woman, who worships but cannot love her. Lerner closely resembles Alex Maitland, the celebrity fiction writer and flashy hero of The Day Before Spring, who returns to his tenth college reunion, and tries to seduce the woman he eloped with unsuccessfully 10 years earlier. Lerner is like the idealist King Arthur in Camelot, who wants so much to do “the right thing,” and leave a legacy for which he’ll be remembered. Pursuant to Lerner’s fascination with psychiatry and time travel, he is On A Clear Day’s Dr. Mark Bruckner who falls in love with a woman 200 years before his time, the woman he can never have. There’s a great deal of Alan Jay Lerner in the two men of Gigi, playboy lover Gaston Lachailles, and his uncle the older roué Honoré Lachailles, who “thanks heaven for little girls.”

Lerner’s own political ambitions were revealed in his choice of heroes in 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, where he became Presidents George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Ulysses S Grant among others. A less flattering Alan Jay Lerner may be found in Lolita, My Love’s Humbert Humbert, Nabokov’s celebrated child molester, an unlikely subject for a musical. Broadway’s most successful librettists may often have written with a distinctive voice, as with Oscar Hammerstein, Arthur Laurents or Hugh Wheeler, but seldom put themselves so visibly on stage.

If Agnes deMille had explored new opportunities for dance in the musical plays of Oklahoma!, One Touch Of Venus, Bloomer Girl and Carousel, this Brigadoon afforded her new opportunities to tell even more of the story in pure dance. For authenticity, deMille enlisted the help of James MacGregor Jamieson, an expert in Scottish dancing, “to instruct the cast in authentic movements of the Highland fling, sword dance, sheann truibhas, and reels” which deMille adapted for Broadway purposes.

As Miles Kreuger goes on to say, Lewis and deMille set out “to neutralize the operetta-like goo in the story.”

[Such words sound like heresy to Ohio Light Opera enthusiasts!!] “deMille took a red pencil and crossed out whole sections, suggesting to the authors where she felt dance could tell the story better than dialogue. Thus, the entire ending of Act 1, beginning with the wedding dance, and followed by the interruption of the savage sword dance, is brought to life through movement and music. The opening of Act 2, in which the villagers pursue Harry Beaton, a rejected suitor, through the woods to prevent him from leaving the village and thereby destroying Brigadoon, is also a pure invention of deMille. The return of Harry’s dead body, a passing point in the original script, was developed by deMille into a stunning funeral sequence with authentic Scottish bagpipe music played onstage.” In hindsight, I’d prefer to think that Lewis and deMille gave Brigadoon its guts.

Robert Lewis writes: “One bone of contention was the ending of the show. It was a quiet finale with the dominie Mr. Lundie leading Tommy off into the misty light to join his Scottish love in the disappearing Brigadoon. Many people, Fritz Loewe among them, felt this was too downbeat an ending, and we should somehow contrive to get the villagers back for a rousing finale, so beloved of musical comedies. Standing in the back of the theatre one night during the Boston tryout, I heard Harriet Ames, one of the musical’s most important backers, whisper to Cheryl Crawford, “The show’s great but when are you going to change that awful ending?” “Over my dead body,” replied Cheryl. It was this uncompromising attitude that made it possible to bring Brigadoon into New York with the integrity of the production intact—no mean feat in the history of musicals.”

What can we say of Fritz Loewe’s involvement in “Brigadoon”?

Composer Frederick Loewe. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Credit him with finding the story in the first place, recommending it to Lerner, who effectively re-imagined it for modern American audiences. For Berlin-born and classically trained Loewe, what kind of music could be expected? In a later television interview, Fritz reportedly explained, “There aren’t many Scottish tunes. Actually I based the music for Brigadoon on Brahms. His work sounds Scottish. You can’t be slavish, especially to influences that aren’t that plentiful. You have to keep the freedom to compose.” Later critics would identify operatic antecedents such as Christoph Willibald von Gluck as Fritz Loewe’s inspiration, not the pop melodies of Tin Pan Alley.

By way of answering that tiresome question, “which comes first the music or the lyrics?” Lerner and Loewe had a rather unique method of collaboration. First the book was largely blocked out, and the pair would discuss the placement of a song, who would sing, and how it related to the plot. As biographer Edward Jablonski put it, “this procedure would frequently suggest a title, or an idea on which to build, or in Lerner’s words, “a thought and its mood. Fritz then sets it to music, then writes out the music. [Lerner reads music.] Lerner goes away to sketch out a rough lyric, then next meeting tries it out on Fritz. Often they would sit together while Fritz let his imagination run over the keyboard, with melodic phrases and rhythms. Jablonski adds, “When something caught Lerner’s attention, he would say, “Wait! That’s it!”” Through this process of repitition and refinement, stop and go, back and forth, a finished song would emerge.

Gene Lees’ biography of the Lerner & Loewe collaboration quotes an interview between Tony Thomas and Lerner: “I said to Fritz one day, “Isn’t there any real Scottish music other than Loch Lomond?” He answered, “Well, the most Socttish composer I know is Edvard Grieg.” So one day over at the library I looked it up and discovered that Grieg’s family name was MacGregor. Either his grandfather or great-grandfather had come to Norway from Scotland. You find that open fifth running all through Grieg. It was very characteristic of Grieg’s music and it’s characteristic of Scottish music, and it can be seen in Hungarian and Czech and German music too.” Worth a mention is Loewe’s distinctive use of a quarter note rest in the duet “Almost Like Being in Love.” It’s like a musical hesitation, listen and you will hear, “Why it’s, [rest] almost like being in love.”

Although not one song was cut or changed radically from the start of rehearsals until New York opening, a few earlier minor changes may be noted. “The Heather on the Hill” was originally a solo, but Bobby Lewis felt as a duet it would highten the interplay between Tommy and Fiona. Reportedly, Marion Bell recalled that the lyrics to “Love of My Life” were so risqué that Pamela Britton’s Meg Brockie was embarrassed to sing them. Indeed, of Meg’s two songs, “Love of My Life” was not even recorded for the original cast album on RCA Victor in 1947, and “My Mother’s Wedding Day” was “cleaned up” for airplay.

It wasn’t until Columbia Records recorded a studio cast of Brigadoon in 1957 for conductor Lehman Engel, Shirley Jones and Jack Cassidy in the leads, than Susan Johnson recorded “Love of My Life.” Let us consider that Meg’s “Love of My Life” suggests a young girl’s adventures with pre-marital sex; “My Mother’s Wedding Day” celebrates her parents’ drunken wedding, with the punchline that she knows, because she was (old enough to be) there! Comparison of the New Haven and Boston tryout programs confirm the paucity of changes. The billing of James Mitchell, the original Harry Beaton, was elevated to that of the other six principals on the title page; Jeff Warren, the actor who played Sandy Dean, was replaced by Hayes Gordon.

Trude Rittman later described her working relationship with Fritz and Alan in an oral history interview with Nancy Reynolds at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts in December 1976: “[Lerner and Loewe were,] well, very inspired guys. Fritz is a musician, how they come very rarely these days. A wealth of melodic invention. A wealth. A very lazy wealth. You know I usually have to write down things. We worked a great deal together because I really record what he writes very often, and we discuss while it is going on, while he improvises. He would do very often enormous spontaneous work. I’m like a mirror. We are old friends… (NR: Well, when you say you take it down, does he sing it to you something or other?) No. He is a brilliant pianist virtuoso. And I write it down. He could do that himself. As a matter of fact, Brigadoon he wrote every note. He had no money to pay anybody. But later on, from then on I’ve written down every show for him. And I really am… as I say, it is like a mirror. Like a reflector. And it is, of course, marvelous….. Because somebody listens and observes and watches and says, “I think you could do that much more beautifully.” … “And Alan is of course a great procrastinator. They work together in the most miraculous way, but as human beings they are not making out so well with each other. Alan is not a particularly nice person. I say that very softly into the machine. And there is a lot of grievances between them, as it sometimes goes…” Trude Rittman later noted that Fritz wrote out all of his dance and incidental music, unusal for a Broadway composer. As their mutual trust and respect evolved, Fritz would allow Rittman more latitude in each of their later shows together.

In my examination of the Fritz Loewe manuscripts at the Library of Congress, there exist several abandoned music fragments, call them mere themes or dramatic ideas, or Lerner’s “thought or mood,” but with no extant lyrics:

“The Ballad of Jamie MacLean”

“Dancin’ Day”

“Gavotte”

“Jeannie’s Wedding Day”

“The Miracle”

“Nothin’ Like a Man”

“She Doesn’t Hear Me”

“Wooin’ in the Highlands”

“True Love”

“We’re Very Lucky”

“I Insist”

“Have a Morning”

Brigadoon ran for 18 months (581 performances), and afterwards toured America for another year and a half. Between 1950 and 1967 it was revived six times by the New York City Center, usually with its original sets and costumes, and three times by the NYC Opera between 1986-1996, and once on Broadway in 1980 for 133 performances. Meanwhile back to 1947, Cheryl Crawford, Robert Lewis and James Jamieson prepared to take Brigadoon back to its eponymous Scotland home and London’s West End, under Prince Littler’s auspices, in the spring of 1949. Fritz and Alan were unable to join the English production, although three of its male stars, Philip Hanna as Tommy Albright, Hiram Sherman as his buddy Jeff Douglas, and James Jamieson doubling as Harry Ritchie and re-stager of de Mille’s dances, were American.

Friend of director Robert Lewis, Ian Wallace, himself a n opera singer and son of a Scottish MP, was retained by Prince Littler as the production’s Scottish advisor, and consequently several of the Alan Jay Lerner’s Scottish character names were altered to conform to historical accuracy. The disgruntled suitor Harry Beaton and his happier brother Archie became Harry and Donald Ritchie, respectively. Fiona and Jean MacLaren found their clan re-named MacKeith. Mr. Lundie, keeper of the village’s secret, reappeared as Mr. Murdoch. Charlie Dalrymple, Bonnie’s Jean’s groom-to-be, became Charlie Cameron. Among the lesser townsfolk, Angus McGuffie took the new sur-name of MacMonies, and the inconsolable Maggie Anderson became Maggie Abernethy. Whereas Broadway’s Brigadoon jumped in time from the present 1947 back two centuries to 1747, Wallace, with an eye towards Scotland’s turbulent history with England and the banning of kilts, suggested 1735 and 1935 as more plausible, historically quiet moments for Brigadoon’s elusive village to appear. Broadway costumer David Ffolkes had unwittingly dressed Brigadoon’s peasants in royal Stuart tartans, which was corrected for the West End. With the help of a dialect consultant, the English cast assumed authentic Scottish accents superior to their American predecessors; the authenticity of such production details were noted by several London critics, unexpected for an American musical. Its London run of 19 months (685 perfs) at His Majesty’s Theatre was an equal triumph; it was revived in 1988 at London’s Victoria Palace Theatre for 327 performances.

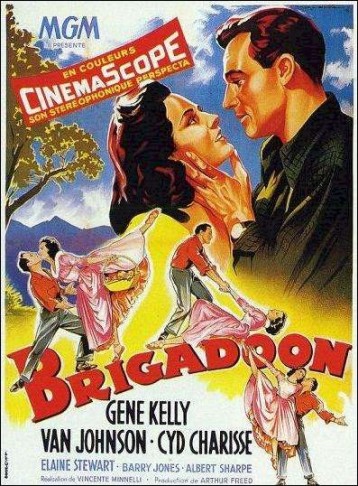

Brigadoon was produced in Australia (1951), Mexico (1960), Germany (1980) and Japan (1980s), and was adapted as a spectacle on ice (1953), MGM film (1954), musical for television with Robert Goulet and Sally Ann Howes (1966), and filmed for Dutch television in 1964. Back to its Hollywood iteration, Gene Kelly wanted so very much to film Brigadoon on location, but the unpredictable vagaries of Scottish weather made it financially impossible to maintain a cast and crew on full payroll. Dore Schary and the risk-averse MGM powers-that-be ruled no, and so MGM’s Technicolor Brigadoon today looks embarrassingly artificial, its colors absurdly chromatic. Following on the success of An American In Paris, Alan Jay Lerner, Gene Kelly and Vicnente Minnelli reunited.

French poster for the Hollywood version of “Brigadoon.” (Photo: Wikipedia)

Lerner’s screenplay dispensed with the comedy numbers “My Mother’s Wedding Day” and “Love of My Life,” at the request of the Breen office. Also dropped were “Jeannie’s Packing Up,” and “The Sword Dance.” Kellys’ vocals were thought unsatisfactory so “There But for You Go I” and “From This Day On” were also cut, although the pre-recordings exist. When one considers that Cyd Charisse’s vocals as Fiona were also dubbed, I think you’ll agree that MGM’s Brigadoon made a dance-action-romance spectacle, but shortchanged the comedy and the musical score. The 1966 tv version, widely viewable on YouTube, restores most of the music cut for the film (except “Love of My Life”), but is likewise marred by the incongruous sight of Hollywood hills which in no way resemble Scotland, cheesy studio sets for the village, and the equally silly updating of the story from 1947 to 1966.

Unlike Can Can and many other musicals of this era, Brigadoon’s libretto had withstood the test of time, and has seldom been tinkered with. If you want to acquire a recording of Brigadoon, may I recommend the EMI-Angel 1991 studio cast recording conducted by John McGlinn, starring Brent Barrett, Rebecca Luker and Judy Kaye. Nice as the 1947 RCA is, its’ 32 and a half minutes playing time can’t compare with the 79 minutes of the McGlinn. I have a fond spot in my heart for Columbia/now DRG’s 1957 studio cast with Jack Cassidy, Shirley Jones and Susan Johnson too.

Ohio Light Opera’s strengths are well-matched to the demands of Brigadoon. The full orchestra, robust singing by principals and ensemble, and its romantic story proved exceptionally compelling. Nathan Brian was born to play Tommy Albright, and he was well-matched by the Fiona of Katherine Polit.

OLO’s veteran Ted Christopher somehow made Mr. Lundie’s explanation of “Brigadoon”’s miracle plausible to modern ears.

And the substantial choreography required by the Sword Dance, Funeral Procession, The Chase, MacConnachy Square, Wedding, Jeannie’s Packing Up, and Come to Me, Bend to Me, were admirably staged. What a pleasure to see and hear Brigadoon revived on such a grand scale.

Here in Hull, N.East England I feel remote from Broadway but have spent all my life following American and Viennese musical theatre. My mother took me to see “The Merry Widow” age13 in 1943 as bombs fell around the city. I am just completing a massive VISUAL History from 600BC Greek Drama to the present day. Your background on F Loewe and ‘Brigadoon’ is fascinating. Many thanks BILL BROMWICH

terrific.. i’ve always been a huge Brigadoon fan and though I so wish it had been shot in Scotland, the fantasy is so rich, one looks past it. would like to know where I could hear versions of the omitted songs.