Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

11 August, 2021

Most operetta fans will know Paul O’Montis because he made a famous recording of “Was kann der Sigismund dafür, dass er so schön ist?” which is a ‘camp’ contrast to the version sung by Siegfried Arno at the world-premiere of Im weißen Rössl in 1930. O’Montis didn’t perform in many operettas, but he wrote quite a few before the Nazis arrested him and put him into a concentration camp for being gay. Now, a well-researched biography by Ralf Jörg Raber has been published, outlining O’Montis’ career that made him “popular with elderly ladies and young gentlemen,” as the title promises.

The cover of Ralf Jörg Raber’s book “Paul O’Montis – Biografie eines Vortragkünstler.” (Photo: Metropol Vlg.)

Paul Emanuel Wendel was born in the small Hungarian town Újpest on 3 April, 1894, to a protestant family that soon moved to Riga where Paul went to school, before embarking on his extraordinary path as a “Vortragskünstler”: an artist who performs chansons and sketches. He started out in Riga, and when he was 17 years old, he wrote his first operetta libretto: a vaudeville he called Comtesse Rokoko, performed at the Deutsches Stadttheater in Riga by Kapellmeister Fritz Koreny-Schenk, who also wrote the music and had his wife Hermine Hoffmann-Koreny-Schenk as the leading lady.

The Deutsches Stadttheater in Riga. (Photo from Ralf Jörg Raber’s biography, Metropol Vgl.)

This was followed, a year later, by Die fromme Klotilde, set in France and dealing with Parisian bon vivantes and so called “Lebedamen” (prostitutes) who are contrasted with the prudish lady of the title. According to a 1913 newspaper report there were “ovations” on opening night!

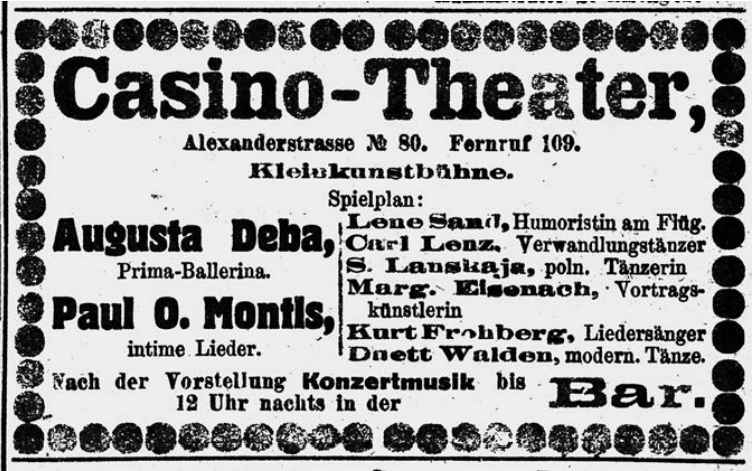

In his book, Mr. Raber chronicles the various operetta experiments in detail, including a 1913 Fledermaus parody by O’Montis called Die Göttermaus oder die Flederdämmerung. But the focus of O’Montis’ career was not to be operetta, but chansons. He started making a name for himself during WW1, singing in a Russian prisoner of war camp. He escaped on Christmas 1917 and landed in the midst of the Russian Revolution, performing in St. Petersburg at a Kino-Varieté where no one suspected that he was “German.” Working his way back to Riga he appeared at the Casino-Theater with “intimate songs,” as the program states.

An annoucement of Paul O’Montis appearing at the Casino-Theater with “intimate songs.” (Photo from Ralf Jörg Raber’s biography, Metropol Vgl.)

Such “intimate songs” with strong sexual undertones became his specialty. They brought him to Munich and Berlin. In Germany, O’Montis wrote more operettas, Das blaue Mieder with music by Siegwart Ehrlich was published in 1919.

Paul O’Montis’ operetta “Das blaue Mieder,” the sheet music can be found at Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. (Photo from Ralf Jörg Raber’s biography, Metropol Vgl.)

Ehrlich is best-known today for his song “Ich bin die Marie von der Haller-Revue“ which Lea Seidl sang before becoming a West End star in White Horse Inn. Ehrlich also wrote the song “Amalie geht mit’m Gummikavalier”.

In 1930 O’Montis also wrote Der Dritte im Bunde, with music by Frank Stafford, it premiered in Leipzig on 29 May at the Neues Operettentheater des Centraltheaters, in close vicinity to Paul Abraham’s Viktoria und ihr Husar. Der Dritte im Bunde is about a so called “Hausfreund,“ i.e. a lover who is introduced into a marriage as a third party to form a “throuple.” It was very much in sync with sexual morals of the late 1920s. In 1933 O’Montis also published the operetta Prinzessin Casanova, it was to be his last.

A 1931 caricature of Paul O’Montis from “Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger.” (Photo from Ralf Jörg Raber’s biography, Metropol Vgl.)

O’Montis appeared in various films in the early 1920s, all of them lost today. He published novels and short stories, and basically tried making money any way he could. Until he finally managed to establish himself in the mid-1920s. Critics praised the “securely balanced technique” with which he presented “new piquant chansons” that were fun and totally over-the-top. He was hired to perform on the radio and made many recordings. These recordings are the basis for his lasting fame. It’s the repertoire Max Raabe has made famous decades later with a style modelled on O’Montis, possibly the most famous “Nance Character” in German chanson and cabaret history.

O’Montis toured all over Europe, with the two songs “Kuno, der Weiberfeind” (by Rudolf Nelson) and “Madame Lulu” (by (Harry Waldau) as particular audience favorites.

A 1930 announcement of a Paul O’Montis concert. (Photo from Ralf Jörg Raber’s biography, Metropol Vgl.)

Mr. Raber analyses many of these songs closely, he also looks at the way some of the songs avoided being taking out of circulation by the 1927 “Gesetz zur Bewahrung der Jugend vor Schund- und Schmutzschriften,” which is a law comparable to today’s anti-LGBT legislations in Hungary, Poland, or Russia, designed to “protect” young people from anything “queer” and “different.”

O’Montis is – next to Wilhelm Bendow, the star of many Erik Charell shows – one of the most famous gays-on-record. In 1927 he recorded “Was hast du für Gefühle, Moritz?” which is a perfect early example of LGBT music.

Was hast du für Gefühle, Moritz, Moritz, Moritz

Sind’s kühle oder schwüle, Moritz, Moritz, Moritz

Du sagst nicht Ja, du sagst nicht Nein

Du bist so fein, und doch gemein

Du hast ein Herz für viele, Moritz, Moritz, Moritz

Du bist zu schön, um treu zu sein!

As Mr. Raber points out, O‘Montis never talked about his homosexuality publicly. There are no statements by him, or by others, only veiled comments. In 1930 a reviewer in Riga wrote that O’Montis “doesn’t pay any attention to the beautiful sex,” which Mr. Raber calls an outing of sorts. Mr. Raber can only speculate who O’Montis might have had relationships with.

What we know comes from later court documents that hint at him having been in a relationship with his pianist Theodor Jakob Schmidt (aka Teddy Sinclair) and with another one of his later pianists, Franz Hasl.

Paul O’Montis recorded a wide repertoire, including Emmerich Kálmán’s “Gräfin Mariza.” (Photo from Ralf Jörg Raber’s biography, Metropol Vgl.)

After the Nazis rose to power in 1933, they kept a close watch on O’Montis and the people he worked with. And it didn’t take long for the police to strike. He was arrested in Cologne after a performance, apparently because of political statements he had made. As the investigation went on, sexual encounters with young men were also examined. This lead to O’Montis being sentenced to one year and nine months in prison because of violating §175, the notorious paragraph that criminalized male homosexuality.

When O’Montis was free again in 1935 he emigrated to Switzerland and tried to (successfully) restart his career there and in Austria. He also performed in The Netherlands in 1936 and in Czechoslovakia in 1938, as well as Poland. He made his last record in April 1937 (“Danke schön, es war bezaubernd”) before ultimately emigrating to Yugoslavia. What happens afterwards is somewhat muddy.

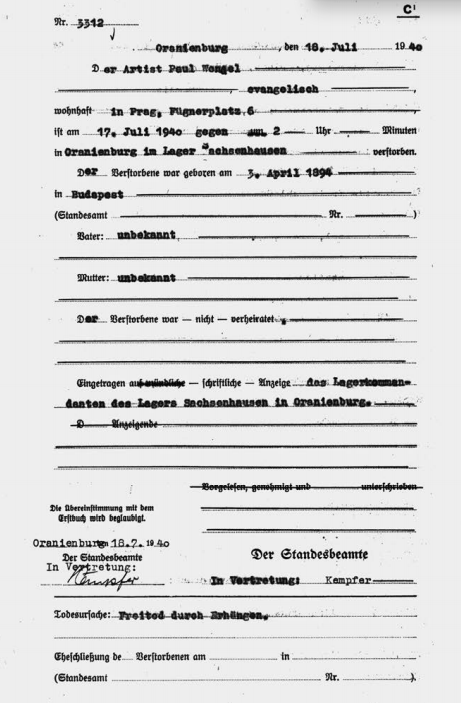

He was registered in Prague in September 1938 where he was again arrested for homosexual activities, or as it was officially called: “Unzucht gegen die Natur.” When the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia, O’Montis was technically back in Hitler’s Germany. And in 1940 he was brought to the concentration camp Sachsenhausen, just north of Berlin. It was infamous for being a camp for homosexuals who had to wear the pink triangle. They had little chance of survival because of the drastic treatment they received.

On 17 July 1940 O’Montis was killed. Officially he hanged himself, which was called “suicide.” But, as Mr. Raber outlines, such “suicides” where commanded. The “Blockälteste” (“elders on the block,” i.e. other prisoners, in this case a political prisoner who seems to have enjoyed torturing “queers”) saw to it that these commands were fulfilled. Reading that chapter in the new book is chilling, and a reminder of the not so well-known horror in places beyond Auschwitz.

After WW2 Paul O’Montis was forgotten, no one in Germany was particularly interested in hearing his story or listening to his “frivolous” songs at a time of severe neo-prudery. Not till 1962 did a recording of O’Montis show up on an LP released by Electrola, it had Friedrich Hollaender as conferencier.

In 1976 a first full O’Montis album appeared, merely stating that “O’Montis was killed by the Nazis.” No further details were given. And then another 20 years passed until a first CD came out.

Paul O’Montis made many recordings for Odeon Elecrtics, and he appeared regularly in the most famous cabaret venues in Europe. (Photo from Ralf Jörg Raber’s biography, Metropol Vgl.)

West-German literature on the history of cabaret steadfastly ignored his name. East-German authors also kept him out of books such as Kabarett von gestern (1967) or Das Chanson im deutsche Kabarett 1901-1933 (1980). Only Helga Bemmann mentions his name in the context of KaDeKo in Berliner Musenkinder: Memoiren (1987).

Today, his recordings can easily be found on YouTube, and they are part of various collections of “Frivollous Songs” or “Gay Chansons” from the 1920s.

It took till now that the Bundesstiftung Magnus Hirschfeld sponsored a new book, published by Metropol Verlag (which had earlier published Operette unterm Hakenkreuz, in collaboration with Staatsoperette Dresden). It’s astonishing to see how long lasting the erasure of an artist like O’Montis by the Nazis can last. Which makes this new “Biografie eines Vortragskünstlers” not only overdue but an important statement.

The fact that this book by Mr. Raber is so full of details, so meticulously researched and so well written makes it a special reading pleasure. It balances the tragic ending with a celebration of what O’Montis achieved as a “Vortragskünstler,” and it openly addresses the problems of reconstructing the private life of someone who had to hide his homosexuality because of §175.

The death certificate of Paul O’Montis from Stadtarchiv Oranienburg. (Photo from Ralf Jörg Raber’s biography, Metropol Vgl.)

It would be worth translating this book into English and making this story available to people outside of German speaking regions. And, yes, it would be fascinating to hear some of the operettas O’Montis wrote. If they are anywhere as funny as his chansons, then they would be well worth rediscovering.

Hi. Huge fan of O’Montis and have a recording of just about every one of his records. I’ve also managed to obtain from Prague archives, copies of arrest papers and further information about his death. The body was sent to Hartheim for cremation.

O’Montis sang many of Willy Rosen’s songs which I have catalogued. There were many other cabaret stars that went to camps.i have recording on my YouTube channel – jonjamg

https://textundmusikvonmir.co.uk/

Further to my comment about the record concerning the death of Paul O’Montis, it states Hartheim. Paul could have been sent to Hartheim and gassed. It seems rather a long way for a dead body to be sent for cremation. Whatever he was murdered. Friends were not allowed to view his body. The death certificate was issued but isn’t necessarily true. It would not be the first and definitely not the last death certificate to be falsified. In 1940 the Nazis were still observing false niceties.

It’s a pity that the illustration of “Das blaue Mieder” is so poor. A version in color can be seen online at the Notenmuseum. See the listings for Wolfgang Ortmann, the artist (1885-1969), who was my grandfather.