Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

15 November, 2017

In February 2017, theater historian Dr. Wolfgang Jansen is organizing a conference on the topic of “Popular musical theatre under Socialism.” It will take place at the Zentrum für Populäre Kultur und Musik (Center for Popular Culture and Music) in Freiburg, Germany. We spoke with the Berlin based researcher about the shows he and his colleagues will be dealing with. And we asked him why this topic has been mostly ignored by operetta researchers in the past.

Theater historian Wolfgang Jansen, who also teaches at the UdK in Berlin. (Photo: Ralf Rühmeier/UdK)

Why is it important, today, to look at operetta and musicals under socialist regimes – and have we moved far enough ahead in time to properly evaluate the phenomenon from a critical distance? Or are we still in the midst of things?

It’s the first time that such an international conference takes place. I’m very glad to be organizing it, together with my colleges Dr. Michael Fischer and Dr. Wolfgang Fuhrmann. Representatives from Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Russia will participate. The response we received from the academic world in these countries has been extremely gratifying. It shows that there is a huge interest in discussing “our” topic. Everywhere, scientists research the fundamentals that help understand the developments during that era. Before 1990, there was only little possibility to speak about it freely.

Till now, we certainly know too little about the popular music theater in the German Democratic Republic. And almost nothing is known in Germany from the other Eastern European, former socialist states. To reach a deeper understanding of the development in die GDR you can’t refer only to the Federal Republic in the West. It was a totally different system. You have to refer, instead, to other socialistic countries. But there’s the problem: we repeatedly encounter the European linguistic borders, which make scientific exchange – as we see it as a-quasi daily practice within the English-speaking professional world – almost impossible. I therefore hope that this conference will be able to overcome the language barriers for two days and organize an exchange of information that will deepen our understanding of operetta and musical comedy during the years of socialism.

I already noticed, during my numerous talks, that the respective national research in the Eastern European countries has brought far more fundamental results than we, here in Germany, have come up with while researching GDR operetta history.

A vintage LP with some of the greatest hits from the DDR, including “Mein Freund Bunbury”.

As you mentioned, one of the topics will be operetta in Eastern Germany, before the fall of the wall. Why do you think that researchers of German language operetta have so completely ignored the works created and performed with success in the German Democratic Republic until 1989?

It hasn’t been completely ignored. But it’s true, there are only a very few researchers – musicologists or theater historians – who have shown interest in the popular musical theater of the GDR. Why that is so remains unknown. Maybe the topic seemed not important enough after the collapse of communism? Maybe it seemed impossible to get a inside-look into the political system by analyzing operetta? Maybe the works themselves seemed not “qualified” enough, because none of them continued being successfully performed after 1990? A lot has already been published about cultural life in the East. I am thinking of texts on the history of cinema, dance, or music. But a comparatively detailed, basic, source-oriented and time-critical study of popular music theater is missing. However, I am happy that there will be various colleagues at our conference who will present new research results for the first time. I hope this will improve the operetta research situation for the future.

You will also discuss commercial Broadway musicals and the circulation of American ideology on GDR stages. Is that something that could fascinate American fans of Broadway musicals too?

Dr. Laura MacDonald from England will discuss this. Her presentation is not about Broadway musicals themselves, but about their reception in the GDR. In the mid-1960s, the first musicals could be seen there. The first were My Fair Lady and Kiss Me, Kate, later Cabaret, Man of La Mancha, Anatevka, Hello Dolly and Show Boat. However, despite their successes, they were secretly distrusted by the state to be “subliminal carriers of capitalist American ideology.” It must be remembered that those were the Cold War years, and the United States of America were the enemy. For example Cabaret: it shows how the German fascists hated the Jews. But in the GDR the main goal of showing fascists was to demonstrate how they killed as many communists as possible. In Cabaret there are no communists, nor in any of the other musicals. So what were the concepts that led theater directors to put on the shows anyway, and what about the audience’s reaction?

I am looking forward to hearing the results of Mrs. MacDonald’s research. I expect that there will be big differences regarding the perception of Broadway musicals in East and West Germany, because of the different social and political systems.

Zentrum für Populäre Kultur und Musik in Freiburg, Germany. (Photo: Michael Fischer)

Are there recordings of these productions?

There are some recordings of operettas and musicals: studio recordings, which were distributed as LPs or singles. As far as I know, an exact list has not yet been made. But live recordings, as they were published in the Federal Republic for the first time in the early 1970s (Hair), do not exist, as far as I am aware.

An LP from East Germany, released by the company Amiga, with various classic Broadway musicals.

Regarding the style of performance, we encounter similar problems as in the Federal Republic and in Austria. They are the result of casting musicals with “traditional” operetta singers, or pop musicians. Well-trained German speaking musical comedy performers did not exist, back then. The first state-organized training courses were established at the end of the 1980s! The standards of operetta, as it was understood at the time, were applied to musical comedy: beautiful sound of the voice and orchestra, very little psychological acting, and again and again trusting in the art of opera singers. But the longer theater directors were concerned with musical comedy demands, especially in serious works after the late 1960s, the more it became apparent that these shows are a different genre than operetta, with requirements that not be fulfilled by a standard operetta ensemble.

You yourself will talk about shows imported from “fraternal socialist countries.” What are the shows, and how are they different to the shows from the GDR?

In the Federal Republic the popular musical theater was increasingly influenced by American and British imports. The situation in the GDR is less unilateral, due to governmental control. Almost an equal number of operettas and musicals came from so-called “fraternal socialist countries.” Today, the titles of the US musicals are well known, while the plays from Hungary, Poland, the Soviet Union, or Romania, which have been on the stage since the early 1950s, have fallen to oblivion. At the same time, the early imports, especially from the Soviet Union, were regarded as exemplary examples for an ideologically impeccable, socialist operetta.

I will try to trace the aesthetic and thematic development through the breakdown of communism by means of show-by-show analysis. From the other participants, I hope to find out how far the translations corresponded to the original librettos. For, unlike in English, an evalutation of this is not easy, even if you hold the performance material in your hands. Language barriers are a hindrance.

The inside of Deutsches Musicalarchiv in Freiburg, Germany. (Photo: Ralf Rühmeier)

A focus of the conference will be on Hungary. Obviously, Hungarian operetta à la Kalman, Lehar and Abraham is an important sub-genre and internationally very successful. Why have most operetta researchers ignored the developments in Hungary after the 1930s, and why haven’t they taken the special performance histories of shows such as Csardasfürstin into consideration?

This is certainly a true observation for German-language operetta research. However, I suspect that this is not equally applicable to the research carried out in Hungary itself. Dr. Heltai from Budapest, at least, will tell us how the Hungarian foreign policy used the Budapest Operetta Theatre in the interstate cultural relations to promote the image of a “prosperous” socialist Hungary. The presentation focuses on the history of a highly politicized touring version of Die Csárdásfürstin. The socialist adaptation of this Kálmán operetta, equipped with a new, anti-aristocratic libretto, premiered in 1954. It was shown in Moscow and Leningrad, in Bucharest, Italy and Austria. Based on reports from Hungarian diplomats, Mr. Heltai will finally outline the indented political goals and the actual gains of these international tours.

The last lecture is entitled “Primadonna with no Male Lead, The Dramaturgy of Hungarian State Socialist Operetta,” presented by Prof. Magdolna Jákfalvi from Budapest. Do you already know what she’ll be talking about and who the primadonna with no male lead is?

In August 1949, theatres in Hungary were nationalised, and only three of the pre-war acting legends stayed with the Operetta Theatre: Hanna Honthy and two comic actors. The lecture will demonstrate how the pressure of this limited cast changed the dramaturgy of the whole genre, and which artistic strategies created the current peculiarity of Hungarian operetta-performances and operetta-writing: operetta without a strong male lead. The research reveals how the theatre survived the forced import of Soviet culture under the leadership of the director Margit Gáspár, and how during the harshest years (1949-1956) it succeeded in turning a bourgeois genre into a Socialist one. The analysis focuses on the creative choices of actors and the administrative choices of the director in following operetta’s path into the supposed glory of State Socialism – with a female director and a lone prima donna. [For more information, check Magdolna Jákfalvi’s essay on “Hungarian Operetta From A State-Socialist Perspective” in our archive.].

Which language will the conference be held in? Is it accessible to international visitors?

The conference languages are English and German. The relatively few German speakers are invited to provide an English summary of their lecture for the listeners. In this respect, the conference is suitable for international guests. For further information, please contact me at: wolfgang.jansen[@]web.de.

Generally speaking, the English language research world completely ignores what is examined in the Germany speaking world, and vice versa. Will you publish the papers in German and English, so that everyone can learn something?

As usual, the lectures will be published some time after the conference. The Center for Popular Culture and Music has a suitable series. A separate English and German version is, however, yet not planned.

An early edition of Richard Traubner’s book “Operetta: A Theatrical History,” 1983.

There are many who claim operetta is a totally apolitical genre – and they love the romantic plots and music precisely because they consider these shows free of the tragedies and horrors of complicated world politics. Yet you and the people you have invited to Freiburg will demonstrate the opposite: the influence of politics on operetta and musical theater. Is it a new trend, to not blend out politics when discussing operetta? (Can this trend spread to the UK and USA too, or are the cursed, forever, with Richard Traubner’s ‘fluffy’ vision of operetta?)

Well, to me it’s not a contradiction. I am a theatre historian. Therefor I am just doing my job as well as possible. On the other hand, I love to see popular music theatre. And I am enjoying great performances.

But as a historian I must stress: in principle, the works of the popular musical theater, whether musicals or operettas have meanings and put out statements. They can be banal or challenging, dealing with the everyday interpersonal life or existential questions of mankind, or sometimes even having political or religious aspects. To recognize that and to describe what this means, is necessary for the understanding of the individual shows as well as for the genre itself.

In addition, the works are grounded in a cultural and temporal context, which sometimes, more or less clearly, imprints itself onto the works, influences the life and thoughts of the authors and composers, and determines the genre’s history. Contextualization is therefore not arbitrarily. This does not diminish, in any way, the individual pleasure of the works themselves, the enjoyment of good music, or the interest in the happiness of the protagonists. However, to me a serious scientific research of popular music theater has to be based on methods of analysis, which are applied in other academic disciplines dealing with historical subjects too. Popular musical theatre can be much more than just “fluffy” feel-good entertainment.

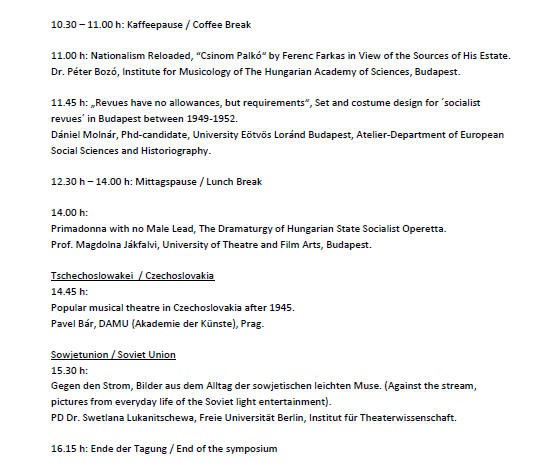

Here is a list of the scheduled talks for the conference.

List of talks at the conference “Populäres Musiktheater im Sozialismus.” (1)

List of talks at the conference “Populäres Musiktheater im Sozialismus.” (2)

List of talks at the conference “Populäres Musiktheater im Sozialismus.” (3)