Dario Salvi

Operetta Research Center

25 December, 2017

As a conductor and operetta researcher, I have been working, for the last month or so, on restoring the orchestral parts and score for Gustave Kerker’s The Belle of New York, a musical comedy in two acts, with book and lyrics by Hugh Morton. It opened on Broadway at the Casino Theater on the 28 September 1897. Why Belle of New York, I hear you ask. Well… it has interesting music, reminiscent of Offenbach, Lecocq and Sullivan, as one critic said. It has a fascinating story, as all great operettas have. But – here’s the rub – song lyrics contain phrases that make you think of paedophilia and child abuse, not to mention lines about Asians that we, today, would consider politically totally inacceptable. They represent a ‘late colonial type of crude racial stereotyping’ of Chinese people. So how do you deal with that when you wish to revive a show such as Belle of New York – can you revive it at all under these circumstances?

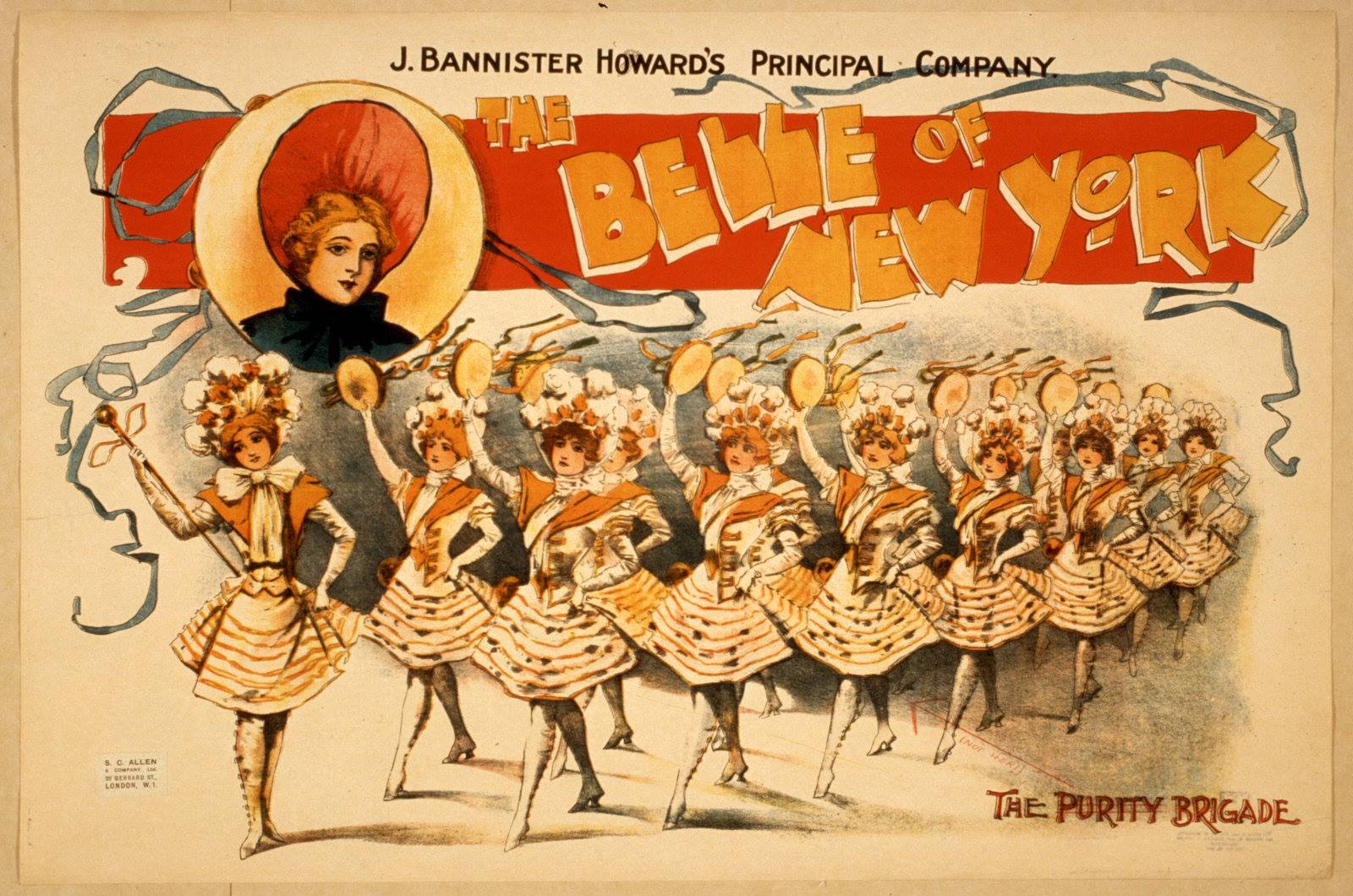

A flyer for “The Belle of New York” from New York, 1898. (Photo: Collection Dario Salvi)

Before I talk about that, let me briefly sketch the story of the show and tell you about the critical reception Belle received in New York and London. The plot deals with Harry Bronson, son of Ichabod Bronson, President of the Young Men’s Rescue League (Y.M.R.L.), of Cohoes, NY. He is celebrating his 21st birthday. He is to be married at noon to Cora Angelique, the Queen of Comic Opera. While in a fuddled state he receives a telegram from his father, stating that he is coming to New York to work up a crusade against vice.

Poster for the “Belle of New York” featuring the so called “Purity Brigade.” (Photo: Collection Dario Salvi)

This is followed by the arrival of the bride and bridesmaids, her father, “Doc” Sniffkins, and the two Counts Rattatoo, each of whom want to marry her.

This party is followed by that of Kissie Fitgarter, a dancer, and her friends, who claim that Harry has trifled with her affections. Harry still further complicates matters by falling in love with Fifi, his French chef’s daughter.

Cora, however, is bound to get him, but they are interrupted by the arrival of the Y.M.R.L., lead by Ichabod, whom, surprised at what he sees, casts his son off penniless, and all leave him but Fifi. Harry falls a victim to the charms of Violet Gray, a demure little Salvation Army lassie, who is known as the Belle of New York, and whom Ichabod has made heiress to all his money.

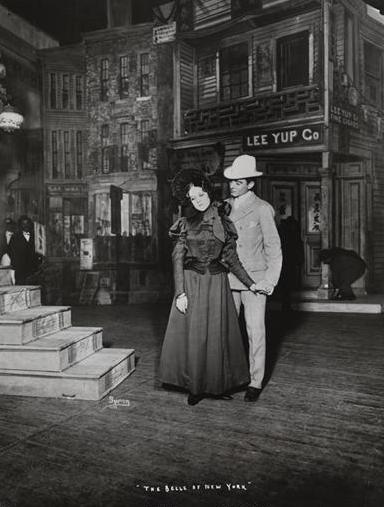

A scene from “Belle of New York.” (Photo: Collection Dario Salvi)

Harry, without means of support, gets a job at the soda fountain in Smyler’s candy store, where Fifi finds him. Violet Gray also, who has made a lasting impression on his heart, finds him there, and proposes a plan whereby she hopes to disgust his father and thus restore him to favour. Harry, however, refuses to listen to the plan, and they are interrupted by the arrival of a German lunatic, whose mission is to kill “Mr. Bronson”, and who has a strenuous interview with the elder gentleman. Violet begins her plan to disgust his father, which she attempts at Narragansett, where, after a vain struggle to carry it out, she faints in Harry’s arms. Harry tells his Father all about it, and everything ends up happily.

A 1898 review from the “Police News.” (Photo: Collection Dario Salvi)

After the New York premiere, The New York Times wrote, “The new burlesque, or extravaganza, at the Casino is as big and showy, as frank and noisy, as highly coloured, glittering, and audacious as the best of its predecessors.” It found the libretto “with no great attempt at original wit in the prose dialogue, but with a few characteristically happy turns in the lyrics,” and the music “reminiscent of Offenbach and Lecocq and Vasseur and Sullivan and David Braham but it is always Kerkeresque.”

The London press was welcoming but nonplussed by the piece. The leading theatrical paper The Era wrote, “The Belle of New York is best described as bizarre. It is like nothing we have ever seen here, and it is composed of the oddest incongruities. … The music is decidedly above the average of musical play scores … it is the brightest, smartest, and cleverest entertainment of its kind that has been seen in London for a long time.” The Standard also thought the music “much above the average” and “distinctly Offenbachian in melody and orchestration.” The paper praised all the performers, particularly “the unctuous humour of Mr. Dan Daly as the elder Bronson, the adroitness of Mr. Harry Davenport as his scapegrace son, the chic of Miss Phyllis Rankin as the Parisian soubrette, and the sweet voice of Miss Edna May as the Salvation maiden.”

Edna May and trumpeters in “Belle of New York.” (Photo: Collection Dario Salvi)

I am currently working on restoring the original orchestral score and parts. I am well into Act 1 and I have come across a slightly controversial issue. The text for the song number 10 called “Little China Girls” is very much of its time. I will report an extract of the promptbook before carrying on with my observations:

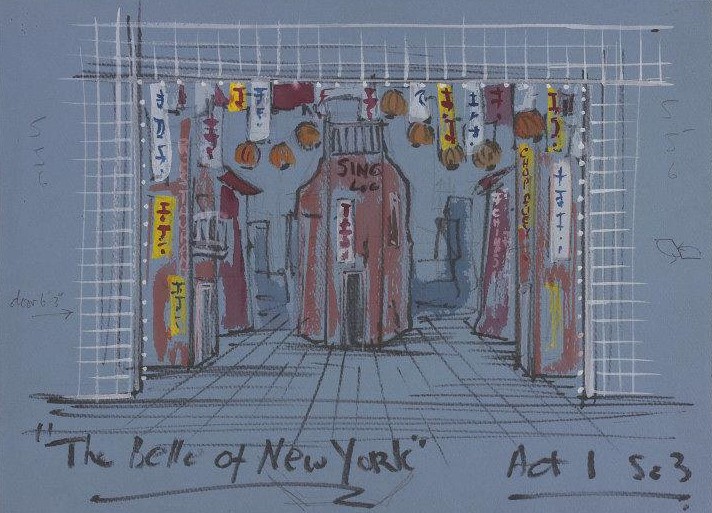

ACT 1, Scene 3: Pell Street, New York, on the Chinese New Year’s Eve. The view is looking op through the end of the street to Chatham Square. The scene is copied from life.

On the right a Chinese restaurant, decorated with Chinese flags and mottoes. Paper lanterns are strong across the stage and lighted. The backdrop has view of Chatham Square with the elevated rail- way station in distance. It is late at night and lights shine from the windows. (MUSIC) At rise of curtain the stage is filled with a promiscuous crowd of revellers and sightseers.

It is a fixture of an uptown crowd and a downtown crowd. The well dressed people are walking about and gazing at the scene of revelry, as if it was strange to them, while the others are skylarking, shouting and running about and behaving like a crowd out for a holiday. There are several China-men in the crowd, some dressed ordinary, laundry- men, but a few of them made up as dignified middle aged men in the rich garments of Chinese merchants. There are girls and tough men, and one or two small boys.

The crowd separates and a Chinese ballet enter at music cue.

The China Town scene from “The Belle of New York.” (Photo: Collection Dario Salvi)

N.10 CHORUS (During Ballet)

Pretty little China girl, velly, velly nice

When she gets alone way off, ching, ching,

Take a little china girl put her on the ice,

Make a little china girl, cough, ching, ching,

Tickle tickle, tum tum.

Tickle tickle tum tum,

Take a little yum, yum,

Ting aling aling.

Little mutton chop, chop

Little ginger pop, pop,

Give her to the cop, cop

Send her up to Sing Sing,

Hi-ya – hi-ya

Kick a little foot up high ah.

Hi, yi. yi, yi

China girl kickie up skyhlgh.

(Repeat refrain)

Pretty little China girl, velly, velly nice

(Enter Harry and Fifi from restaurant L.2.E. He wears a sack suit and derby hat. She is dressed in a summer street dress)

Harry: Well, this is Chinese New Year in Pell Street, Fifi. Do you still love me?

Fifi: Oh, oui! And you? (Embracing him)

Harry: Of course. Now suppose I take you into the Chinese restaurant, give you a bird’s nest pudding and then send you home to papa.

Fifi: Oh Harry! You’ve broken my heart.

Harry: And you have broken my cash account – left me with a suspender button and a quinine pill.

Conductor Dario Salvi and his Imperial Vienna Orchestra.

I discussed the context of the lyrics with my friend Dr. Robert Ignatius Letellier and we came to the very same conclusions. I quote here his words:”The librettos uses a ‘late colonial’ type of crude racial stereotyping of Chinese people perceived as ‘coolies’ (and makes fun of their accent and of the sound of their language). It focuses on the ‘little girl’ image common in the Victorian Age (for example Charles Dickens and Lewis Carroll) which now seems uncomfortably redolent of paedophilia/child abuse (a very current social obsession) and the text could also be perceived to play into the hot topical ideas of gendered sexual harassment, in which one has only allege some sort of inappropriate gesture to be condemned. (Something that also happens in Madama Butterfly on a more serious level, with American military treating Japanese girl adolescents as sex objects).”

What I am debating is if the text should be changed in the modern adaptation of the show or if it should just be performed as it is, to retain an historically correct context and flavour. Maybe all this “Ching Ching, Chop Chop, Pop Pop” is nothing more than a collection of sounds, nothing more than language used for its sounds more than its meaning – maybe we need to stop giving every word we hear far too much importance and consider the real intentions of the person that uses that word. Maybe “Ching Ching etc..” is just sheer childish fun, and innocent (naïve) use of something that now we see as not politically correct at best.

Food for thought. And for a lot of discussing. It’s a worthwhile discussion, because we need to come up with an answer. You might recall that ORCA already touched upon the subject earlier. (Click here for the article “Blacks Doing Yellow-Face.)

Thank you ORCA for publishing this. I would be really curious to read other opinions, so please post your comments here.

Thank you

Dario

It seems to me you agonize too much over something you did not create, this can be considered an item of historical interest. It is probably Kerker’s best work and undeniably popular on Broadway of the time.I believe a faithful reproduction would be my heartfelt recommendation.

I heard something about the rights to this work being held captive by some collector in the midwest. Know anything about that?

Bill White

The BELLE was actually a failure in America. But its Americanised version of the style of show produced at London’s Gaiety Theatre proved a hit in London largely through its energy and novelty. The Gaiety girls were inclined to be languid!!! And it went on from there to become the most successful American musical comedy of it’s time OUTSIDE America.

Totally agree with Bill White, if you are going to do a show of this era you need to do it as it was written, ‘censoring’ C19th shows is foolish and wasteful of time.

Kurt

I saw the show in an excellent amateur production(London Transport Players) at Wimbledon Theatre many years ago and remember enjoying it very much indeed. the plot was amusing and the dialogue did not seem dated; the music was very pleasant even if it is a ‘one song’ show, the title number being reprised many times. LPT employed an excellent professional orchestra of about 20. I still wonder why it is not staged more frequently – it works better than The Arcadians which I saw at about the same time.

Having revived several of this era, I say it is not a matter of all or none. None of these shows were Shakespeare in dialog or lyrics and it just may interfere with the audience’s enjoyment if they are cringing.

So, I’ve changed words (the coon song in Florodora, racial reference in A Country Girl), cut songs and sometimes plowed right through. Sometimes these shows have alternative songs from different venues or times you can substitute – or a number by the same composer from a different show.

The Edwardian Musical Police didn’t come and arrest me, and the audience (unaware of any change since nobody had ever seen a production) was entertained. Result.

In the USA, the last thing you want to do is lose a municipal venue because the Cultural Appropriation Investigators have complained (usually because of the title, but some may look up a list of numbers or character names). Not all publicity is good.

But if the audience came away with a newfound appreciation of “Not Gilbert and Sullivan” (Monckton, Kerker, Caryll, Talbot, etc.) and have a few jolly good tunes to hum on the way home, all is good. MK