Laurence Senelick

Operetta Research Center

12 April, 2023

Operetta was one of the most successful forms of theatre to go transglobal in the 19th and early 20th century. The works of Offenbach and Lecocq, Strauss and Lehár easily crossed borders to become common musical currency from Marseille to Yokohama, from Rio de Janeiro to Cairo. These various translocations were taken to be harbingers of modernity.

Ukiyo-e triptych showing (from the right to left) male kabuki actors in a version of Bulwer-Lytton’s “Money” and Western actors in Offenbach’s “The Grand Duchess”. (From: Laurence Senelick, “Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture,” 2018)

Recognizable whatever their metamorphoses, they served as model, incentive, inspiration or alternative. As prime examples of commercial entertainment, their ready transfer from society to society, culture to culture, promoted professionalism in the performing arts. The circulation in our time of the megamusical or the “blockbuster” is only the latest avatar of this phenomenon.

What held true for the French and Austro-Hungarian masters of light opera was not the case, however, for Gilbert and Sullivan. Societies take what they need from imports or innovations, applying their own emphases and coloration. Although Sullivan’s music could be passed by cultural customs officers without duty imposed, Gilbert’s librettos could not. His word-play was too intricate and ingenious for easy translation. Moreover, the attitudes embedded in his characters and plots were too emphatically Victorian for rapid reception abroad. One has to be familiar with English law, politics, education, class attitudes, traditions and tastes to savor fully the comedy, even in the Anglophone sphere. That is why the manager Richard D’Oyly Carte sent Oscar Wilde as “front man” to acquaint the North American public with the vagaries of the aesthetic movement before he opened Patience in New York. (Read more about this here.)

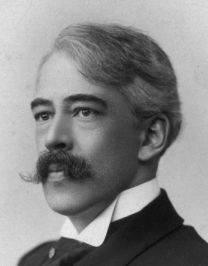

Oscar Wilde during his North America tour.

The one exception to this neglect is The Mikado. It was first seen in Europe when D’Oyly Carte organized a tour of the Savoy Opera company to the Netherlands, Scandinavia, Germany and Austria in 1886. The first German-language production had a runaway success in Vienna in the translation of C. Zell and R. Genée, inspiring a similar furore in Berlin. Overlooking the shafts aimed at English society, this adaptation laid emphasis on the opera’s exoticism.

Rosa Streitmann (middle) as one of the three little maids in “Der Mikado” at Theater an der Wien, 1888. (Photo: Charles Scolik / Theatermuseum Wien)

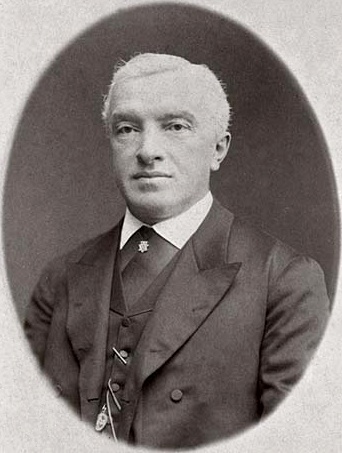

The affluent and influential Moscow industrialist Sergey Vladimirovich Alekseev (1836-1893) made millions from the family business of manufacturing gold and silver thread for ecclesiastical garments. Like so many of his class, risen from serfdom, he was an avid patron of the arts and his numerous children were all stage-struck.

Moscow industrialist Sergey Vladimirovich Alekseev in 1884. (Photo: Unknown)

The eldest Vladimir Sergeevich (1861-1936), known as Volodya, was too subject to stage fright to be an actor, but had talent as a director, especially of musical plays. Konstantin Sergeevich (1863-1938), known as Kostya, Kokosya or Kotun, first took the stage name Stanislavsky in January 1885 and came to be considered the founder of modern acting.

Zinaida Sergeevna, known as Zina (1865-1950); later went on stage under the name Aleeva-Mirtova, and, like Volodya, in Soviet times taught Stanislavsky’s system at his Opera Studio. Anna Sergeevna, known as Nyusha (1866-1936) also took the stage-name Aleeva. Georgy Sergeevich (1869-1929), known as Yura, a talented delineator of character roles, later acted professionally in Khar’kov.

Lyubov’ Sergeevna (1871-1941), known as Lyuba, nicknamed the Moscow Venus, had affairs with the opera singers Fyodor Chaliapin and Leonid Sobinov. Boris Sergeevich (1871-1906), known as Borya, acted under the names Borin and B. S. Polyansky. Pavel Sergeevich (1875-1888) died too young to have a career, but Mariya Sergeevna (1878-1942) became a famous operatic soprano. They all took part in the family theatricals.

The Red Gates in Moscow as seen on a mid-19th-century postcard. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Shortly after Kostya’s birth in 1863, the family moved to a palatial mansion at Red Gates (Krasnye Vorota) in Moscow. Six years later Sergey Alekseev bought an estate in in Lyubimovka, about an hour’s ride from Moscow, on the banks of the Klyazma River. The growing children showed so much enthusiasm for make-believe, dressing-up, circuses and plays, that in summer 1877 he had an annex built there with an auditorium and stage, dressing-rooms, costume shop and props storage. On September 5 it was inaugurated with a couple of short farces.

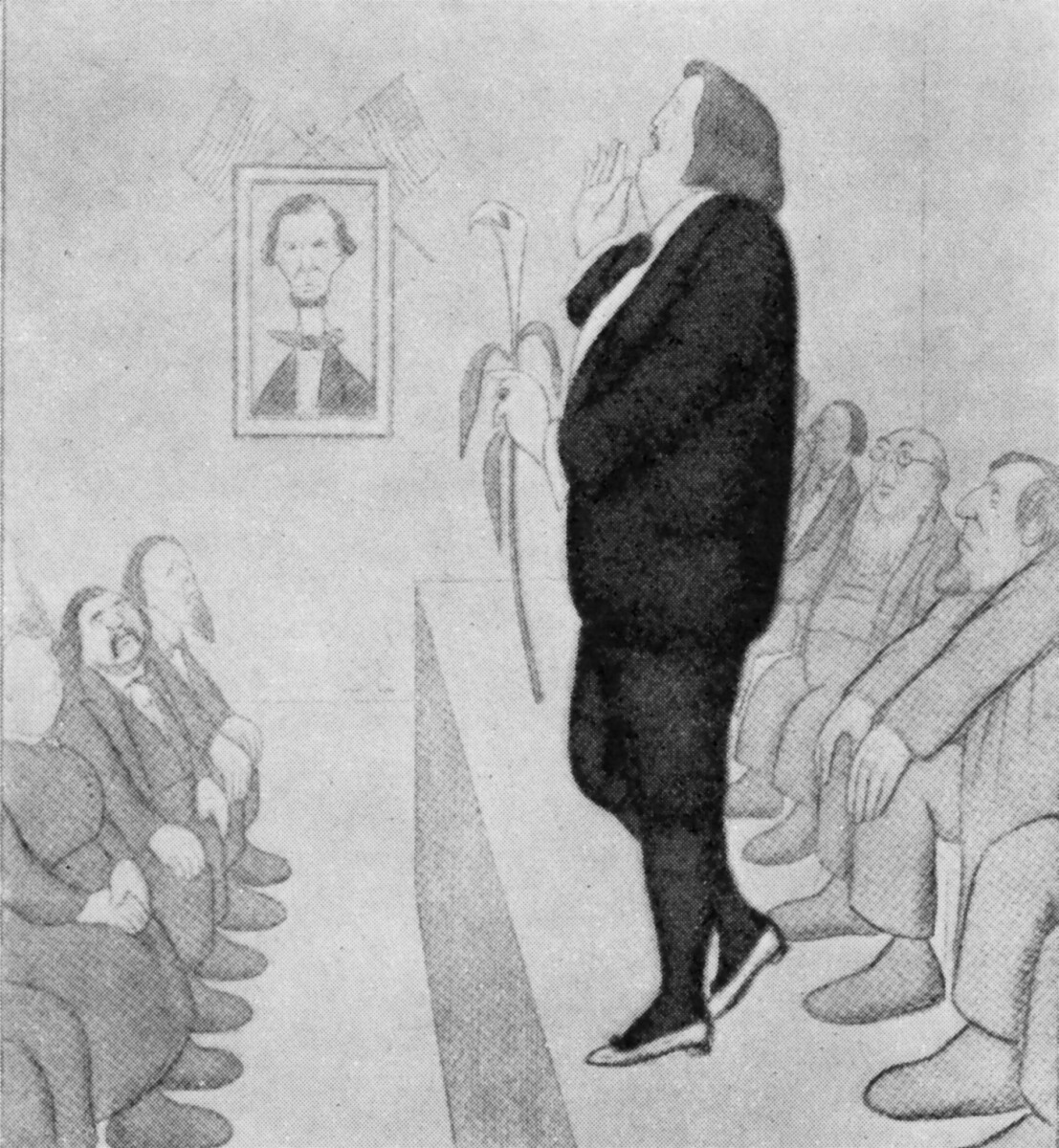

By the time the Alekseev children were teenagers and the eldest girls were married (Zina to the young physician Konstantin Sokolov and Nyusha to Andrey Shteker) their dramatic efforts had become so ambitious that in winter of 1882 a theatre was constructed on the second floor of the Red Gates mansion with a 300-seat auditorium, two dressing-rooms, and a refreshment room for the use of the siblings, their mates and friends. Each presentation of the Alekseev Circle, as it was known, was performed only once to an invited audience; it was launched on April 28, 1883 with three vaudevilles.

Such one-act farces interspersed with songs, mostly translated from French and German, were the stock-in-trade of the repertoire. Since all the Alekseevs were musical (Kostya studied to be an opera singer), they soon staged an operetta: Jonas’ Javotte, adapted by Kostya who also appeared in it in drag. On the same bill, they ambitiously ventured a scene from the third act of Aida with Kostya as the high priest Ramfis. He also co-wrote an opera Each Cricket Knows His Own Hearth with music by F. A. Kashkadamov, a close friend of Volodya’s and son of the brothers’ literature tutor.

The future Stanislavsky, like may budding amateurs, fancied himself a romantic lead. In his diary for January 24, 1884, he wrote, “I’ve been waiting for the role of jeune premier, and a robber in a gorgeous costume. … I copied every actor who came to mind. … In general the role scored a success, I was pleased they thought me handsome. … Given my dramatic aspirations, it is no surprise I forgot I was playing an operetta and performed a drama.”

With his siblings he appeared as Philidor in Lecocq’s Comtesse de la Frontière (La Camargo) and as Floridor-Célestin in Hervé’s Mam’zelle Nitouche, as well as in La Mascotte (all 1884),and as a comic trooper who ages over three acts in Hervé’s, Lili (1887). All these productions were thoroughly recorded in photographs of the characters in costume, preserved in special albums.

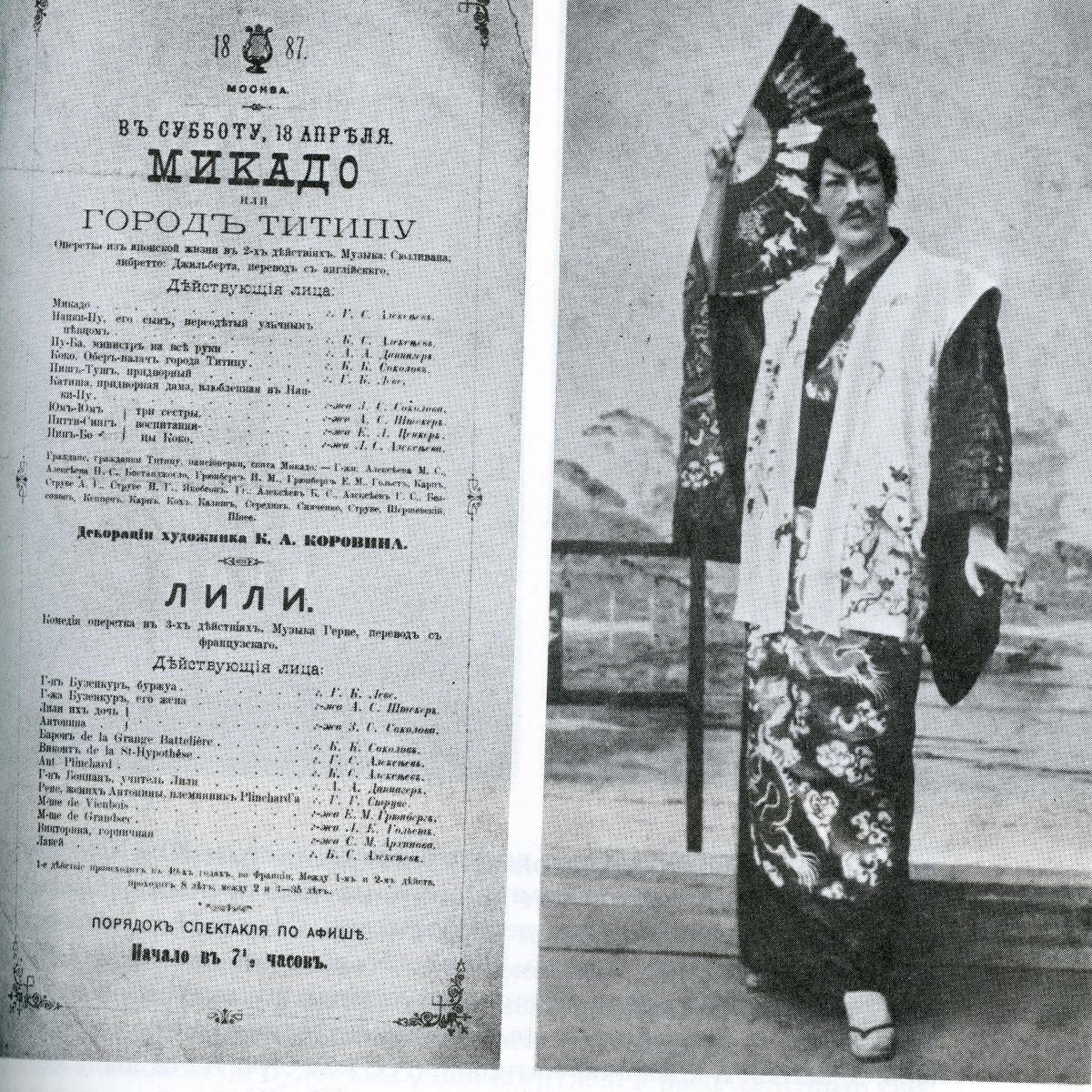

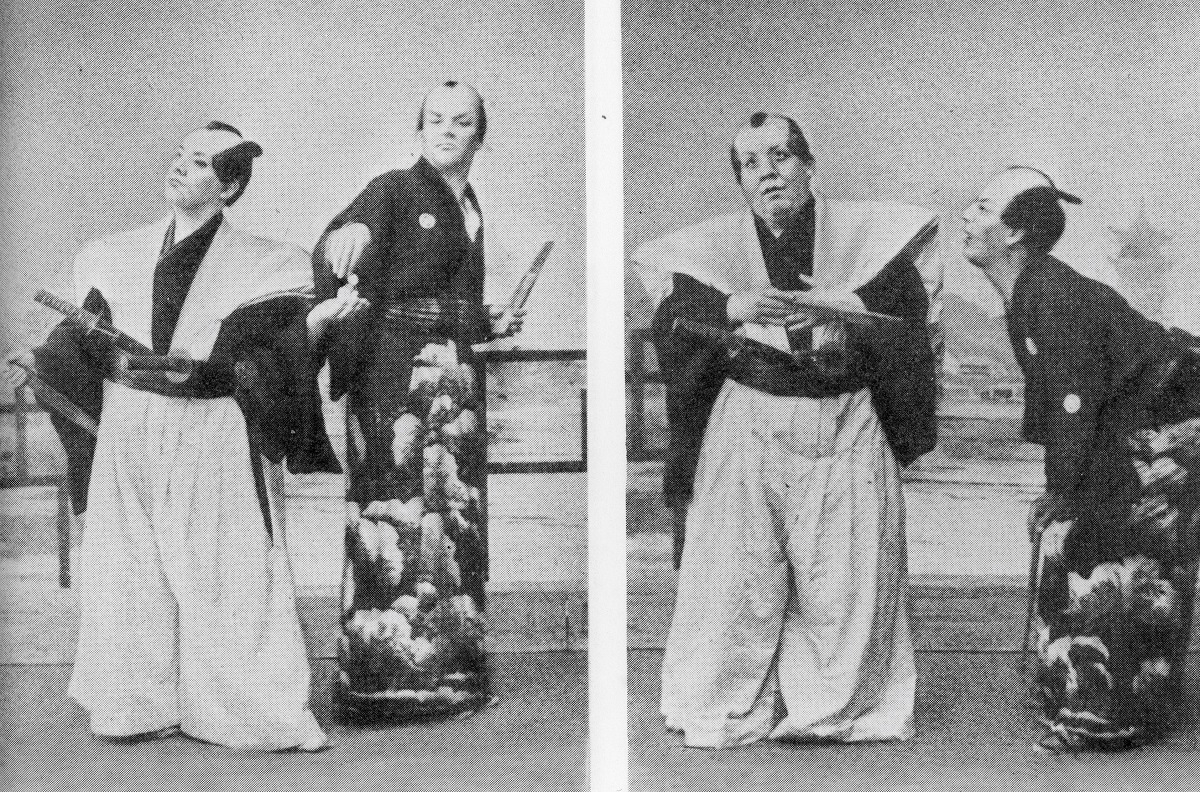

Stanislavsky as Nanki-Poo and his sister Anna Shteker as Yum-Yum. (Photo: I. D’yagovchenko, Moscow)

The culminating production of the Alekseev Circle was The Mikado. How they became acquainted with it is moot. According to Zinaida’s memoirs, she and her husband were visiting Paris in 1886, attending lectures and even surgical operations. Since no French staging of The Mikado occurred until the 1990s, they could not have seen the opera there, although news of a failed Brussels performance or pirated productions in other European capitals may have reached them in newspapers. She wrote about it to her brothers, who, trusting her, asked her to send score and text and ordered real Japanese kimonos from Paris.

The chance to see the work on stage occurred on the way home, for The Mikado was in a hit in Vienna. “Arriving in Vienna, no sooner did we enter the hotel lobby when we saw on the wall posters for The Mikado. Fate itself was favoring us. We wanted to remember in every detail the Japanese gestures and other details of Japanese acting, remember how the kimono is worn, the play of fans, etc. … Back from the theatre in our hotel room, we performed the play of fans, practiced the Japanese gait, rehearsed a few passages, already recalled many of the tunes.” It is unclear whether they saw the D’Oyly Carte production in September at the Carltheater or the German translation at the Carl-Schulze-Theater. that succeeded it.

Program and Stanislavsky (Kostya Alekseev) as Nanki-Poo. (Photo: I. D’yagovchenko, Moscow)

When the piano score arrived in Moscow, the eldest brother Vladimir began to orchestrate it in his head. The English lyrics appeared in the piano score and Kostya boldly announced, “With a dictionary I’ll translate it!” His mother wrote to Zina, who was still abroad in September, “Every free moment Volodya is playing and translating Mikado, doesn’t see or hear what goes on around him, burrows into everything in the English operetta, doesn’t even take tea of an evening.”

“Translation” may be an overstatement. Neither Volodya nor Kostya knew English and no German translation would not be available for another year, so they plagued their sisters Zina and Nyusha who spoke a little English. (English governesses were at a premium in Russian high society.) It is highly unlikely that result resembled anything close to Gilbert’s ingenious rhymes or word-play.

Konstantin Sokolov as Koko, Zinaida Sokolova as Katisha. (Photo: I. D’yagovchenko, Moscow)

The tsarist customs office finally allowed the Japanese costumes through on October 2, 1886: two male outfits for Nanki-Poo (which survive in the Stanislavsky House Museum in Moscow) and four female toilettes. Zina wrote to her mother, “When the costumes were unpacked what a to-do! Of course, in a moment we put them on and it set us in quite a whirl, even Kostya (the male one) – how are kimonos draped? How do you wind the wide sash? Etc. etc.”

The accompanying fans were constantly in play. With his customary humor, the paterfamilias Sergey Vladimirovich wrote to his wife, “I have to tell you, it’s Mikado craziness around here, all you hear is Mikado…and everyone is caught up in practicing with fans. We arrived at Nyusha”s – fans, we come home – fans, finally last night Dantsiger showed up, also with a fan, in short, a wind storm.” (Short, fat Dantsiger was a stage-struck notary who became proficient at juggling fans.)

The cast list for The Mikado reveals just how tight the family circle was:

Mikado: Georgy S. Alekseev

Nanki-Poo: Konstantin S. Alekseev

Pooh-Bah: Andrey Andreevich Dantsiger

Koko: Konstantin Konstantovich Sokolov (Zinaida’s husband)

Pish-Tush: Gustav Karlovich Leve (family friend who took part when needed)

Katisha: Zinaida S. Sokolova

Yum-Yum: Anna. S. Shteker (Nyusha)

Pitti-Sing: E. L. Tsenker

Peep-Bo:Lyubov’ S. Alekseeva

Chorus: Maria S. Alekseeva, Pavel S. Alekseev, Boris S. Alekseev, Georgy S. Alekseev (in Act One), Vasily Nikolaevich Bostanzhoglo (cousin and Lyubov’s future second husband), I. M. Gryunberg, E. M. Gryunberg, L. E. Gol’st, Aleksandr Gustavovich Struve (Anna’s future third husband), S. P. Sennonov, Karp, Kokh, G. G. Kalish, Andrey Kalish, Leonid Valentinovich Sredin (a famous physician and friend of Chekhov), Simchenko, Georgy Gustavovich Struve (Lyubov’s future first husband), Shereshevsky, Shnee et al.

The male chorus for “The Mikado”. (Photo: I. D’yagovchenko, Moscow)

Rehearsals began on October 10. As Stanislavsky remembered it in My Life in Art:

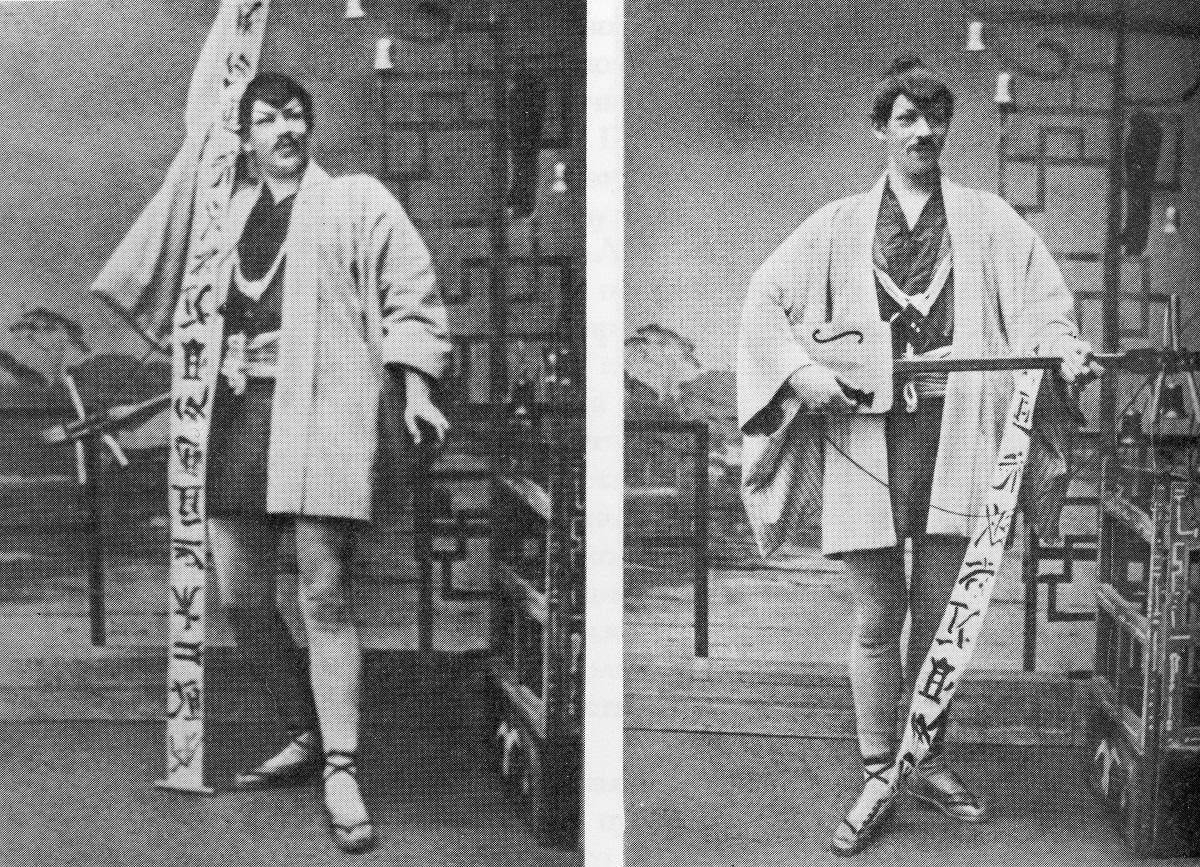

All that winter our house turned into a corner of Japan. An entirefamily of Japanese acrobats, working in the local circus, were with us day and night. They seemed to be very respectable people and, as the saying goes, “fitted in.” The Japanese taught us all their customs: how to walk, deport oneself, bow, dance, gesticulate with fans and master them. These were good exercises for the body. On their instructions all the participants and those who were not were given muslin rehearsal costumes with sashes which we practiced putting on and taking off. The women walked all day with their legs tied at the knees. The fan became a necessary, habitual object for the hands. We even felt the need in conversation, in accord with Japanese custom, to help express ourselves with a fan.

In this respect, the Andreev Circle was ahead of the curve. The artistic fashion known as japonisme began in France in the late 1860s, but was slow to move eastward. It was not until the 1896 that exhibitions of Japanese art were held in St Petersburg and Moscow. The fad crested among the public before the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese war in 1905, but lingered among Russian artists long afterwards.

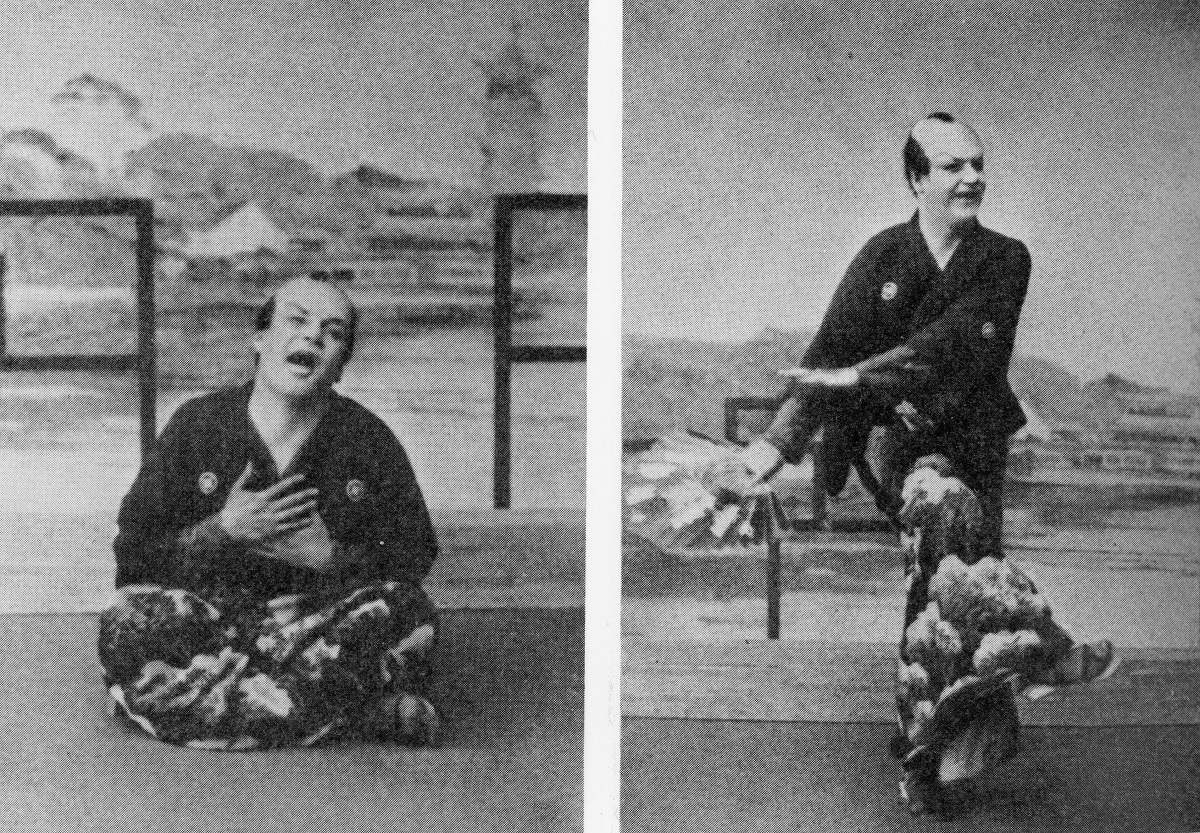

The female chorus for “The Mikado”. (Photo: I. D’yagovchenko, Moscow)

Apparently, it was Volodya who initiated the relationship with the Japanese visitors. In this, he unwittingly was copying W. S. Gilbert, who is said to have brought members of the Japanese Village in west London to Savoy Theatre rehearsals to instruct the actors in their ways. I have been unable to identify precisely which troupe was playing in Moscow in 1886. A marginal note to a draft of Stanislavsky’s memoirs cites Siatara Kavana, but this is not a Japanese name. Tannaker Buhicrosan, the Dutch-Japanese impresario who imported the Japanese exposition to Knightsbridge, may have travelled farther with it. His enterprises, the Japanese Village Company, the New Mikado Troupe and the Imperial Dragon Troupe of acrobats, all visited Australia in April 1886, so may have toured to Russia later that year.

The work proceeded for six months. Stanislavsky went on.

Coming home from the day’s work, we put on our Japanese rehearsal clothes and wore them all evening till nightfall, all day on holidays. At the family dinner or round the tea table were gathered Japanese with fans which, as it were, constantly snapped open or shut. We had Japanese dance classes and the women studied all the seductive ways of the geisha. We learned how to turn rhythmically on our heels, showing first the right, then the left profile, how to fall to the ground doubling up like gymnasts, how to run in time with tiny steps, jump and mince flirtatiously.

This insistence on an ethnographic approach to the opera seems an early foretaste of the Moscow Art Theatre’s later practice, such as bringing an actual peasant woman to sit in on rehearsals of Tolstoy’s Power of Darkness or employing a real artillery officer and fire chief to guarantee authenticity in Three Sisters.

Stanislavsky as Nanki-Poo. (Photo: I. D’yagovchenko, Moscow)

All this practice led to virtuosity:

Some of the women, finally, learned, in time with the dance to throw their fans so that they made a semicircle in the air into another singer’s or dancer’s hands. We learned to juggle with the fan, throw it over our shoulder or between our legs and, most important, mastered all the Japanese poses with the fan, without exception, so that we built up a whole gamut of gestures by the numbers that we fixed throughout the score, like musical notation. Thus, each passage, bar, strong note was defined by its own gesture, movement, action with the fan. In crowd scenes, i.e. in the choruses, each singer was given his own set of gestures and movements with the fan on every accented note, bar, passage. Poses with the fan were assigned to the devised general groupings or, rather, the kaleidoscope of endlessly changing and modulating groups. While some flung their fans, in the air, others lowered theirs and opened them at their feet, while yet others did the same to the right and others to the left, etc. The aim of this expertise was to create an ever-changing stage picture: When in big ensemble scenes this whole kaleidoscope began to move and all the fans, big, medium and small, red, green, yellow, flew through the air the theatrical effect took your breath away.

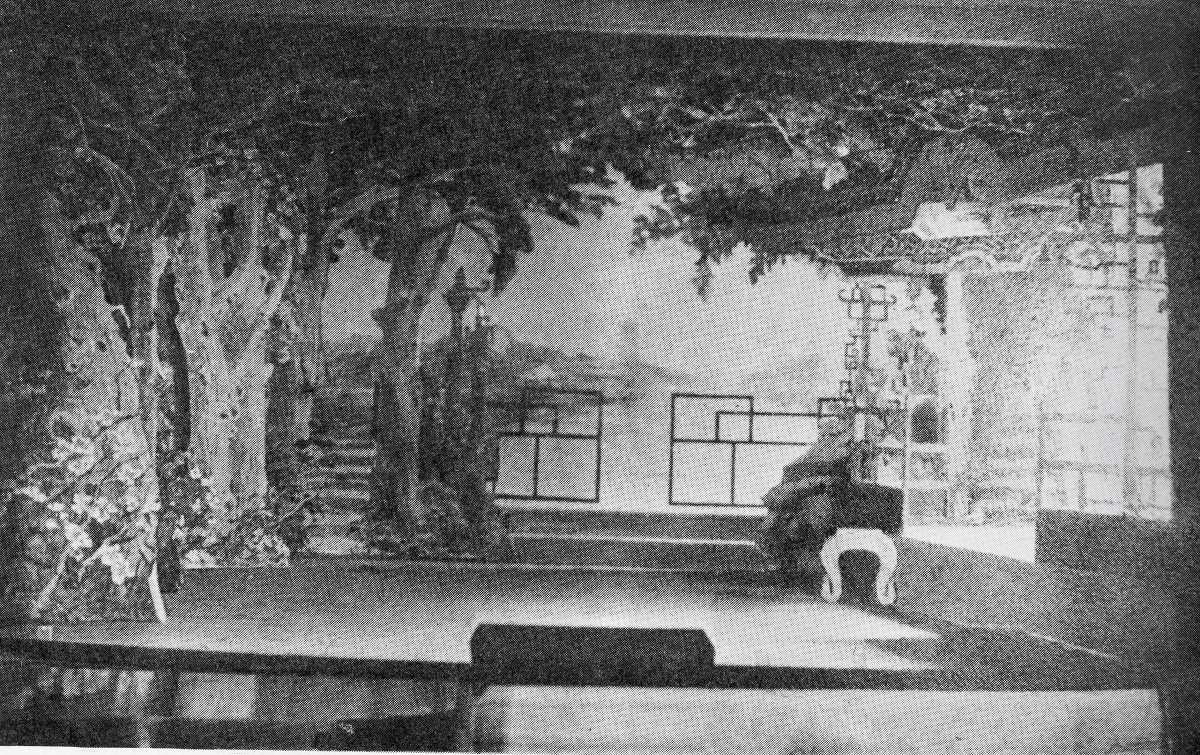

We had put up all sorts of platforms so that from downstage, where the actors lay on the floor with their fans, to upstage, where they stood on the highest spots, the stage, which was not very high, could be filled with fans arching through the air. They covered it like a curtain. Stage platforms were an old but convenient device for the director to use for theatrical grouping. They could be raised or lowered to allow the back rows to be seen.

Add to this the design of the performance the beautiful costumes, many of which were genuinely Japanese, the ancient armor of the samurai, the banners, the elemental japonoiserie, the novelty of the movements, the actors’ dexterity, the juggling, acrobatics, rhythm, dancing, the handsome faces of the young men and women, the excitement and energy, and you can understand our success.

Korovin’s scenery for Act I of “The Mikado”. (Photo: I. D’yagovchenko, Moscow)

In the Alekseevs’ previous production, Hervé’s Lili (which was repeated on a double bill with The Mikado), Stanislavsky had been gratified by its professional polish and the achievement of a genuine “French” mode of speaking. In his notes for the final version of My Life in Art, he praised The Mikado for doing the same thing for Japanese. “The production received its own style, its original, never-before-seen physiognomy.”

That Gilbert’s Japanese were Englishmen in fancy-dress was overlooked by the Alekseev Circle, intent on extracting every ounce of exoticism from the opera.

Despite the impression given in his memoirs, Stanislavsky was not the director. At this point in his life, he regarded himself primarily as an actor. His elder brother Volodya was the prime mover, with Kostya as his assistant. In Zina’s words, “His directorial and production notes and advice were always heeded not only by the troupe but by Kostya. Kostya very much appreciated and acknowledged Volodya. … We all acknowledged him and listened to his instructions same as Kostya did.”

Of the chorus members, Stanislavsky wrote in notes for the final version of My Life in Art: “Every single one knew the notes thoroughly. They had to learn it by ear, as the score was mechanically drummed into their brain. One had to wonder at the patience of my elder brother who achieved brilliant results with them.”

. E. A. Tsenker as Pitti-Sing, Anna Shteker as Yum-Yum and Lyubov’ Alekseeva as Peep-Bo. (Photo: I. D’yagovchenko, Moscow)

According to Zina, “I remember clearly and vividly my first rehearsal after the break (I had given birth to a daughter). … The first chords of the overture rang out. Volodya by his playing inspired the participants even more. My stormy appearance on stage attracted general attention. I glanced at Volodya: nodding his head, he greeted me with an excited look, proudly having observed those sitting in the hall, rejoicing and taking pride in me (he was very fond of me as an actress) and again fixed his eyes on me. He didn’t look at the score, he played from memory. These were mere moments, but I remember and feel them to this day.”

The bulk of the costumes was home-made in pastel colors: apple-green, pink, gold and azure. The scenery also contributed mightily to The Mikado’s professional polish. Modelled on the Savoy Theatre sets, it was conceived and painted by Konstantin Aleksandrovich Korovin (1861-1939), at the time newly graduated from the Moscow School of Painting. Later he became one of the most distinguished artists of the Silver Age, designing for Mamontov’s private opera and the Moscow Art Theatre. A temperamental painter with a subtle feeling for color and responsive to a work’s musical elements, he enriched the pictorial sophistication of stage design.

The artist K. A. Korovin in a portrait by Valentin Aleksandrovich Serov, 1891. (Photo: he Tretyakov Gallery Moscow)

Korovin was attracted to the beautiful Lyubov’ Alekseeva and designed an angel’s costume for her, in which she was photographed. According to fellow designer Aleksandr Benois, Korovin had a talent for telling shaggy dog stories that mesmerized his listeners. Zina recalled “a time after rehearsal at the tea table. Some were in street clothes, others in kimonos. At tea with us was dear, merry Konstantin Korovin. He was asked to imitate Ermolova, Lensky and other actors of the Maly theatre. He portrayed them largely by intonations. Sometimes he added gestures, poses. He impersonated them without caricature or cartoon.”

The premiere of The Mikado took place on April 18, 1887. By this time the Circle’s reputation and excitement about the upcoming show had spread beyond family and friends. Many of the actors Korovin had imitated were eager to attend. After the first performance, the Maly star Aleksandr Yuzhin knocked at the dressing-room door: “How talented you all are!” Savva Mamontov, the millionaire impresario of a celebrated private opera (and cousin by marriage), exclaimed, “Hurray for you!” (Molodets!)

Aleksey Dantsiger as Pooh-Bah, Konstantin Sokolov as Koko in “The Mikado”. (Photo: I. D’yagovchenko, Moscow)

A. E. Blumental’-Tamarin, famous low comic and manager, propagandist for English operetta, eagerly and enviously said that “even in real, professional operetta you rarely see such a performance, such a production and such an ensemble.” In Zina’s words, “We never expected such a success, couldn’t conceive of it! All our hearts were pounding!” For the first and only time, there were repeat performances, on April 22 and 25 and again on May 2.

After their season closed, Kostya wrote on June 13 to his friend and former “crammer” Ivan L’vov:

… without boasting, I will say that the show was remarkably successful. The best proof of that is that we had to repeat The Mikado four times [sic], to a house packed to the rafters with an audience of total strangers. What’s more, after the show most of them asked permission to come and see the show a second time; likewise there were a great many who didn’t get in even once. All the songs were encored two or three times, the ovations and floral tributes were unending. You will find my statements repeated in the papers where some crackpot without our leave printed a whole article of praise.

What’s more, there were inquiries after the first performance from The Russian News and German papers, whose editors wanted to insert their own reviews, but Pater did not deign to permit it. Nevertheless, however jolly the run of performances, it exhausted everyone and me in particular. My nerves are at the breaking point, and I am glad that now I can rest in the evenings and leadthe most decorous way of life.

Sergey Vladimirovich may have proscribed the Russian News (Russkie Vedomosti) because it was a liberal daily. The review that appeared in the Moscow Blade (Moskovsky Listok), although unauthorized, provides valuable details.

A few days ago a respected Moscow businessman Mr A-v staged a domestic performance. … The miniature domestic stage was furnished not only charmingly but artistically. The discipline and intelligence of the choruses, composed of cultured performers, was remarkable. The variegated play of fans during the singing was performed with remarkable skill by the Japanese, beautifully made up and costumed, in time and so graceful that our state impresarios can hardly achieve such discipline on the stages of their own theatres. … Despite the fact that the operetta is performed by amateurs, untrained either in music or the stage, it was excellently rehearsed… [As to the individual performers, they are all] so life-like and witty that many of our operetta actors could learn from them.

Anna Shteker as Yum-Yum in “The Mikado”. (Photo: I. D’yagovchenko, Moscow)

The review singled out Nyusha, now Mrs Shteker, as an “exceptionally attractive” Yum-Yum (“she is lithe, and the variegated play of her fan is very charming and graceful.”) Zina, now Mrs Sokolova, “excellently played the role of the unattractive, overripe noble maiden” and her husband as Koko, “thanks to his fund of unquestionable humor, his well-devised and witty acting offers very dangerous competition for celebrated operetta comics.”

Top honors, however, went to Kostya as Nanki-Poo. “First place is held by the beautiful voice and intelligent phrasing of K. A-v. Despite the fact that the role he plays, by its nature, should be assigned to a more tender and flexible voice [i.e., a tenor], K. A-v in singing knew how to lighten the heaviness of his bass and in performance achieved a certain degree of tenderness and tenorish sentimentality.” (Stanislavsky considered his voice to be baritone.)

The young Konstantin Sergejewitsch Stanislavsky. (Photo: literaturmuseum-tschechow-salon.de)

The only dissatisfied party was Stanislavsky himself. Some 40 years later he recorded in My Life in Art:

I was the only blot on the show. Strange, inexplicable! How can it be that I, one of the directors, assisting my brother to find a new tone and style in staging an operetta, would not as an actor divorce myself from the banal, most theatrically operatic postcard prettiness? Having worked on movement in the empty hall during the summer… in this Japanese production I still could not get away from what I had done previously and still tried to be a good-looking Italian singer. How could I bend my tall, thin figure to be “Japanese,” when all I dreamt of was to make myself taller! So, as an actor, once again I stuck to my old mistakes and operatic banality.

In summer 1888 he wrote to Zina: “You know how popular our domestic performances are. People who were not at our shows hear about us and know all our names… Our scenery and splendor are so famous to all that my name, as stage director, makes them expect something wonderful…”

Konstantin Sokolov as Koko in “The Mikado”. (Photo: I. D’yagovchenko, Moscow)

On The Mikado, that directorial role had been limited to organizing the choruses, but even there he was disappointed with himself. “I achieved decent results, but they were not substantial…the discovery did not penetrate deeply, did not match up with all the other arts. As a plant without roots dries up, so this new-found thing dried up.”

Even the arrangement of the chorus on platforms which he described neutrally in the text of My Life in Art prompted misgivings. The preparatory notes for the American edition of the book contain this passage:

Our grandfathers and great-grandfathers knew better than we how to use them. What is simpler to show those standing at the back than to lower those in front and raise the back rows. When imagination cannot manage to justify an aspect of the mise-en-scène, – all that is left is simply to heap up bigger masses and, without a justified and convincing mise-en-scène, create groups for maximal beauty.

At the time I wasn’t experienced enough to use more subtle artistic means to fill the stage with crowd groupings. I did not know how to show all the participants on stage without piling them up willy-nilly, hiding each another, or how to deploy the company not to the height but to the depth of the stage. Of course, later on, when I had learned this skill, my earlier childish devices seemed ridiculous and stale. But at the time, when the audience still responded to stage hokum, our mises-en-scène were accepted as unusual and made a hit of the production.

More successful in his eyes was the innovative use of rhythm and tempo in stage action, which also affected the audience. “All the movements with the fans were done in time to the music. In those days this was novel. But it was the inner rhythm with accentuation on almost all the strong notes – in unison, and only the specific characters – intuitively – created their own original rhythm to the rhythm of the music, in accord with their individual feeling for the music, text or perezhivanie.” Perezhivanie or emotional experiencing was to become a keystone element in Stanislavsky’s early theory of acting.

The success of these amateurs had reverberations in the professional theatre. No time was wasted in slapping together a Russian adaptation Syn Mikado, ili odin den’ v Titipu (Son of the Mikado, or a Day in Titipu), played at the Setov Theatre and Garden in St Petersburg on 10 June 1887 (the censorship prevented living monarchs from depiction on stage, so the Mikado was replaced by the Shogun).

Front of house of the Mikhailovsky Theatre, 1860s. (Photo: mikhailovsky.ru)

The following year the Zell and Genée translation was staged by a German troupe at the Imperial Mikhailovsky Theatre. In the 1890s, Blumental’-Tamarin, who had praised the Alekseev version, benefitted from its example to produce The Mikado and The Geisha at Lentovsky’s Theatre in Moscow with lavish costumes and spectacular act finales. Occasional stagings would pop up in provincial centers, but neither The Mikado nor Gilbert and Sullivan ever became fully acclimatized to the Russian stage.

Despite this culminating achievement of the Alekseev Circle, in its aftermath Stanislavsky concluded, “Operetta bored me. Besides, on one hand – ever increasing demands in the realm of staging made producing shows expensive beyond our means, on the other hand, my singing lessons with [the bass Fyodor] Kommissarzhevsky drew me to opera. Dreams of a career as a singer possessed me more and more. Partially under this influence, particularly because at the time I was madly in love with our brilliant actress Ermolova, as well as with opera, I dreamed of somehow becoming her partner in drama – operetta ended its days in our circle.”

Konstantin Sergejewitsch Stanislavsky as an older man, as seen in the exhibition “Five Truths – Shakespeares Wahrheit und die Kunst der Regie” (Photo: Theatermuseum Wien)

Even so, towards the end of his life, when he looked back on all he achieved, he wryly remarked to a chronicler of the Moscow Art Theatre, “Mine is une profession manquée. I should have been an operetta actor.”

Main sources (all translations are by Laurence Senelick).

Balašov, Stepan Stepanovič. Alekseevy. Moscow: OKTOPUS, 2008.

Diakonova, Elena. “Japonisme in Russia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,” in Japan and Russia. Three centuries of mutual images, ed. Yulia Mikhailova and M. William Steele. Folkestone, Kent: Global Oriental, 2008. Pp.32-46.

Mihara, Aya. “Professional entertainers abroad and theatrical portraits in hand,” Kushashin kenkyū/Old Photography Study (Nagasaki) 3 (2009): 45-54.

O Stanislavskom. Sbornik vospominanij 1863-1938. Moscow: Vserossiiskoe Teatral’noe Obshchestvo, 1948.

Senelick, Laurence “Musical Theatre as a Paradigm of Translocation,” Global Theatre History 2, 1 (2017): 22-36.

Šestakova, Natal’ija Abramovna. Pervyj teatr Stanislavskogo. Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1998.

Stanislavskij, Konstantin Sergeevič. Moja žizn’ v iskusstve, in Sobranie sočinenii v devjati tomax. Ed. O. N. Efremov et al. Vol. I. Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1988.

Vinogradskaja, I. N. Žizn’ i tvorchestvo K. S. Stanislavskogo. Letopis’. 4 vols. Moscow: Moskovskij Xudožestvennyj teatr, 2003.

Wonderful stuff! Let’s hope Mr Senelick will attack the Italian opera seasons of St Petersburg and Moscow in the same way! It’s so rare these days to find original research of this quality! Thank you!

Fascinating and what ORCA is all about! I would never have associated Stanislavsky with G and S! Many thanks – as Kurt says, more please!!

Wonderful article! I Year’s ago I read somewhere (possibly Opera News?) a reference to Stanislavsky’s having played Nanki-Poo, but without the fascinating details of the family theater, their methods, and the success of the performance.