Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

28 July, 2024

Martin Trageser has published a 150 page book on Carl Millöcker (1842-1899). We spoke with him about this project and what Millöcker as the composer of Bettelstudent and Gasparone means to him – and the world at large – today.

Martin Trageser’s “Carl Millöckers Leben und Werk im Spiegel der zeitgenössischen Presse”. (Photo: Königshausen & Neumann)

You’ve just written/edited a book called Carl Millöckers Leben und Werk im Spiegel der zeitgenössischen Presse, i.e. the life and works of Millöcker as mirrored in contemporary newspaper articles. What gave you the idea for such a book – and what is your aim?

In 2021 I wrote the book Millionen Herzen im Dreivierteltakt, in which I explored the attitudes of the composers of the so-called “Silver Operetta” towards the First World War. During my research, I frequently came across their predecessors and noticed that while there is quite a bit of literature on Johann Strauss II and Franz von Suppé, there is not much on the third member of the group – Carl Millöcker. It was basically my personal interest that drove me to learn more about him. As I began researching, his life and work seemed fascinating to me, and I decided to turn my findings into a book.

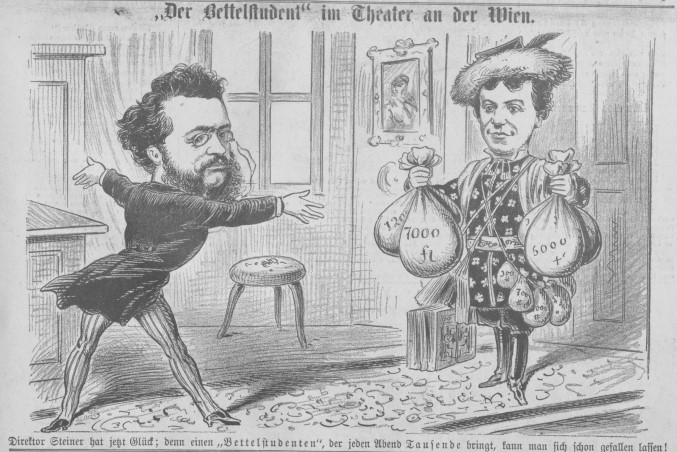

Carl Millöcker (l.) and theater director Steiner (r.) with their earnings from the hit show “Der Bettelstudent”, caricature from “Kikeriki”, 17 December, 1882.

Are you a musicologist, theater studies person, journalist?

I am a high school teacher for German, History, and Politics. I completed my studies with a doctorate on the life and work of Marcellus Schiffer (1892–1932), a cabaret author of the 1920s. Additionally, I am the author of eleven books. After writing two children’s books, I began writing short stories, and in recent years I have published three non-fiction books on operetta composers during the First World War, the Mountbatten family, and in 2024, on Carl Millöcker.

Back in 2011, Marga Walcher published her richly illustrated book Carl Millöcker: Liebe und Leidenschaft des vergessenen Komponisten. It, too, contains many excerpts from contemporary newspapers. How does your book compare to that of Walcher, in your view? And why are contemporary newspaper articles on operetta composers so interesting, for today’s operetta fans?

Marga Walcher’s book is richly illustrated with many photos of Carl Millöcker and his contemporaries, as well as images of objects from the composer’s possession. She places particular emphasis on letters from Millöcker to his second wife, Lina Hofschneider, and letters from Lina to him. Another focus is his friendship with the actor Felix Schweighofer. I have therefore only briefly addressed these two topics in my book, as they are comprehensively covered by Marga Walcher. I have tried not to use the same newspaper articles as Ms. Walcher, although there are still some overlaps. An important source for both of us is, of course, Carl Millöcker’s diary, published in the 1960s. Contemporary reviews provide a very good picture of the time. They reveal the appreciation for the composer, who, after Der Bettelstudent was so successful and popular that, although there was criticism, it was usually mild. If a work was not as successful, critics often blamed the librettists. The reviews also provide insights into the circumstances and backgrounds of performances, as well as information about the singers and directors of the theaters. They not only relate to the respective work but also they reveal quite a bit about the historical context, as well as intrigues and conflicts at the theater houses. Overall, unlike Ms. Walcher, I have quoted the reviews more extensively.

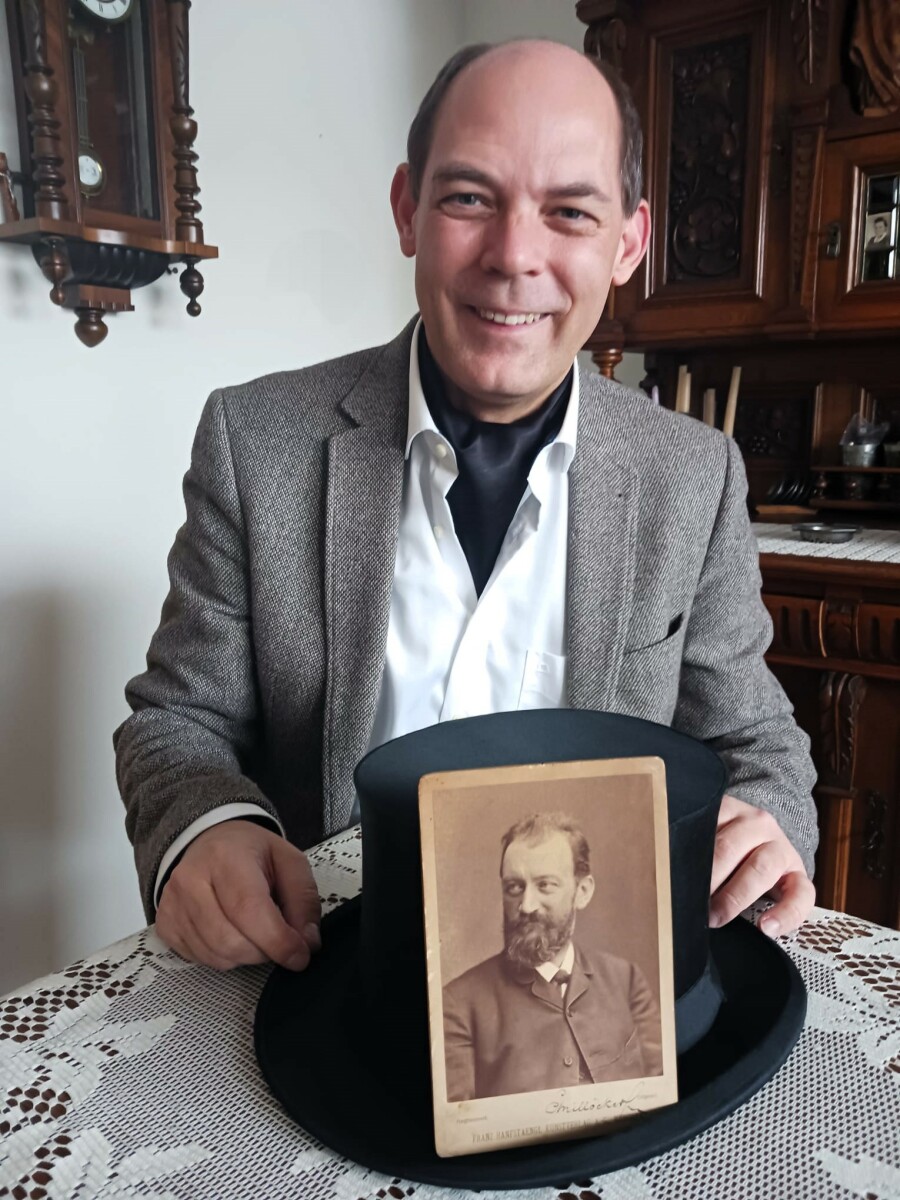

Martin Trageser with a portrait of Millöcker. (Photo: Private)

In her Residenzstadt und Metropole book, Marion Linhardt describes how Millöcker and his works were used – by Austrian nationalists after 1870/71– as a counter-model to Offenbach’s “foreign” and scandalous “French” operettas. He was positioned as the “local” composer and the “non Jewish” alternative, just like Johann Strauss. You do not address this anti-semitic aspect in your book. Why?

I have not read Marion Linhardt’s book. In the reviews of Millöcker’s works from various newspapers, his religion played no role. Comparisons with Jacques Offenbach, on the other hand, were frequent. However, these comparisons always concerned the music. As early as 1867, the newspaper Die Debatte wrote that Offenbach had found an “equally worthy rival” in Millöcker. In Der Floh on June 21, 1872, it was noted: “If one could call Offenbach the musical Heine, then Millöcker would be the Adalbert Stifter in music. So profound, so genuinely Austrian does it blow from his songs to us.” Such comments were frequently found in the reviews of the newspapers, which were my main source. Sometimes they were meant as praise, other times negatively, when it was implied that Millöcker was imitating Offenbach’s style. Judaism was not mentioned in the reviews I read. Naturally, it plays a role, especially after Millöcker’s death in 1899. Since the composers of the Viennese operetta were not Jewish (Carl Millöcker, Carl Zeller, or Carl Michael Ziehrer), they experienced a renaissance from 1933 to 1945. Franz von Suppé, on the other hand, had Jewish relatives and was therefore not often performed in these years. Johann Strauss II also had Jewish ancestors, but Strauss was so popular that his music could not be banned, which is why the entry in the marriage register of St. Stephen’s parish regarding his great-grandparents was corrected.

The authors of the successful operetta “Gasparone”, caricature from “Der Floh”, 3 February, 1884.

The Nazis used Millöcker, later, to promote their own Aryan re-definition of the genre. He appears as a character in the Willy Forst movie Operette, there’s also the very successful Gasparone film with Marika Rökk and Johannes Heesters. From today’s point of view, what do you think about these films? And how do they influence today’s image of Millöcker? (Do you discuss that in your book?)

The film adaptations during the Nazi era and the Federal Republic are mentioned in the book. However, the focus of my book is on Millöcker’s lifetime from 1842 to 1899. There is only a brief outlook on the period after his death, which is why the films are not discussed. There were film adaptations of Der Bettelstudent (with Harry Liedtke) and several adaptations of Gräfin Dubarry during the silent film era. In 1936/37, Der Bettelstudent and Gasparone were filmed by Georg Jacoby with Marika Rökk and the then-little-known Johannes Heesters in the leading roles. Der Bettelstudent was lavishly produced and contains very well-staged dance scenes with Marika Rökk. However, the plot was greatly shortened, and many musical numbers were omitted. In the first fifteen minutes, the plot is set in motion by Colonel Ollendorf’s kiss on the shoulder of Laura Nowalska, which is not shown in the stage version.

The film premiered at the Venice Film Festival and was internationally successful. Despite the changes, it is still worth seeing. Gasparone reunites the dream pair Rökk-Heesters. Leo Slezak is seen as Governor Nasoni. Millöcker’s music is re-arranged, this time by Peter Kreuder. Marika Rökk insisted on a tap dance number in the style of Eleanor Powell, which has nothing to do with Millöcker’s original work.

Both films are worth seeing and entertaining, but one must always keep in mind that they modify the original operettas. As a teacher, I know that a younger generation no longer knows these films. Let alone who Marika Rökk, Johannes Heesters or even Carl Millöcker were. The fact that the films were shot in black and white would already deter young people, and the plot would have little appeal for them. They certainly had an impact on the composer’s image at the time of their creation, but today they are essentially no longer relevant.

This also applies to the films in which Millöcker is portrayed by famous actors. Operette by Willi Forst is very loosely based on the life of Franz Jauner. There are many excerpts from various operettas because Forst wanted to “focus on an entire era” and “give new impetus to the operetta.” In doing so, he deviates from reality. It is hard to imagine Alexander Girardi, Franz von Suppé, and Johann Strauss Jr. playing music together in a pub after the (allegedly unsuccessful) premiere of Die Fledermaus or Jauner helping the crisis-ridden Millöcker with the composition of Der Bettelstudent. The young Curd Jürgens remains colorless in the supporting role of Millöcker.

In Theo Lingen’s film Glück muss man haben, Millöcker is played by Paul Hörbiger in 1950. In the fictional story, Millöcker saves a young man, weary of life, from suicide and gives him advice on love. He tries to matchmake the two young people, but he falls in love with the girl himself. In the end, he remains alone and dedicates himself to music again. Both films are not recommended for today’s viewers and also distort the image of the composer.

Though you discuss the “original” Paris operettas that came to Vienna – and though the shocked press reactions to these “morally questionable” pieces have been chronicled already in 1999 in the book Offenbach und die Schauplätze seines Musiktheaters – you don’t talk about the pornographic side of the genre, and how Millöcker distanced himself from it. What made you decide to skip that topic? Isn’t it a very modern theme?

The librettists of the Viennese operetta primarily aimed to entertain. Their libretti are less frivolous and more conventional than those of the Parisian operetta. “Had we lived in the time when Aristophanes’ Lysistrata premiered, the authors, who certainly possess talent, would also have found the courage, which today is unfortunately disrupted by a ‘morality police’ that interferes not only with operetta life,” wrote a critic from the Extrapost on December 24, 1894, about the plot of Millöcker’s operetta Der Probekuss.

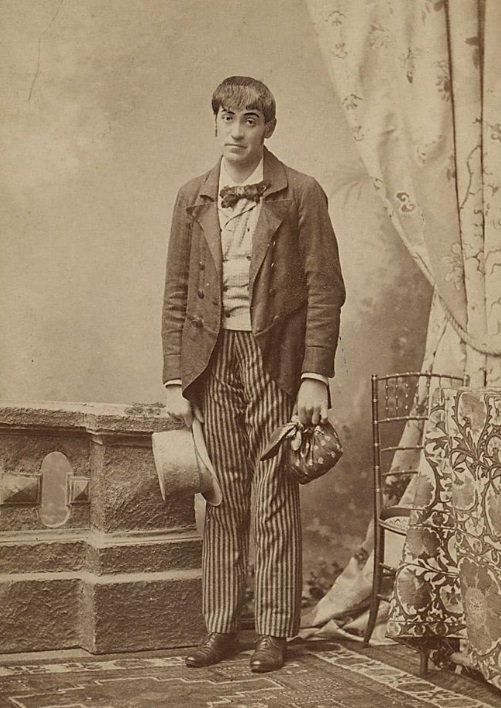

Hermine Meyerhoff as Dubarry in the 1879 production at Theater an der Wien. (Photo: Atelier Rudolf Krziwanek / Theatermuseum Wien)

Richard Genée, who wrote many libretti for Millöcker, admitted in an interview with Curt von Zelau in 1885: “The Offenbachiades with their burlesque texts had outlived themselves, and when I set out to create independent libretti, my aim was to banish the parodistic element and French frivolity from operetta and to pave the way for the creation of a German operetta that should approximate the nature of comic opera.” Thus, in Millöcker’s work, one essentially does not find the “pornographic side of the genre.”

The morally questionable actions include Colonel Ollendorf’s kiss on the shoulder of Laura Novalska, which is not shown on stage, or the theme of the right of “primae noctis” in Apajune, der Wassermann.

Gräfin Dubarry is set in a Parisian demi-monde milieu and deals with a king’s mistress. There are indeed works in which morally questionable scenes occur, but these become increasingly rare over time.

Josephine Dora in Millöcker’s “Drei Paar Schuhe”. (Photo: C. Barsch, Theatermuseum Wien)

I would not necessarily classify questions of morality as a modern theme, because in the Western world, almost anything is allowed, and it is increasingly difficult to shock anyone. The pornographic side of the genre was not of interest to me, as it is virtually nonexistent in the works of Millöcker and other composers of the first generation of the Viennese operetta.

Josefine Gallmeyer in Millöcker’s Das verwunschene Schloss”, 1878. (Photo: Atelier Rudolf Krziwanek, Theatermuseum Wien)

Your book also contains illustrations. Where are they from, and what do they tell us about operetta “Made in Vienna” that might not be so obvious from texts alone?

The images (especially caricatures) come from various 19th-century newspapers that have been digitized and are available online at https://anno.onb.ac.at. The caricatures show, among other things, that operettas and their composers were extremely popular in the 19th century. The composers were big stars whose private lives were just as interesting to the public as their works. Millöcker is usually approached with respect and depicted as an elegant conductor. Occasionally, the great financial success of his works is also hinted at, such as when he is shown sitting on various sacks of money bearing the names of his operettas, or when the highly popular Alexander Girardi brings the director of the Theater an der Wien sacks full of money after the premiere of Der Bettelstudent.

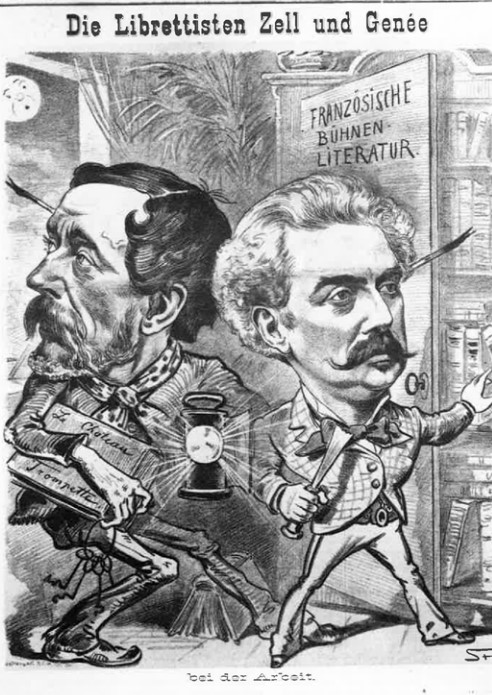

The librettists Zell & Genée “at work” = stealing from French originals, caricature from “Der Floh”, 7 October, 1883.

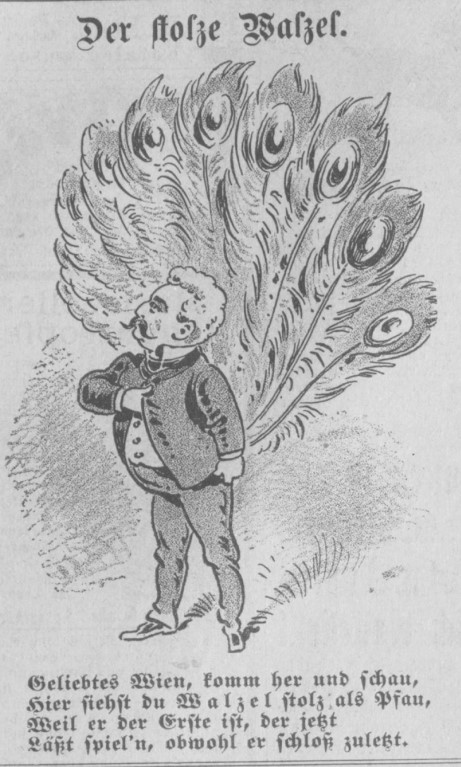

The librettists are treated with less respect. Friedrich Zell (Camillo Walzel) and Richard Genée are depicted in Der Floh, for example, as secretly stealing French stage literature from a library to pass it off as their own works. Walzel, who was also at one time the director of the Theater an der Wien, is often portrayed as vain. The magazine Kikeriki turns him into a peacock, for instance. Often, the performers of the operettas are also immortalized in caricatures. The images show the popularity of the operetta while also poking fun at the character traits of prominent personalities or criticizing the librettists, who usually receive poor reviews.

It is remarkable that the librettists had such a high status, as today they are almost forgotten.

Librettist Camillo Walzel as seen in “Kikeriki”, 29 August, 1886.

Did you ever consider publishing your book in English? There is nothing on the international market on Millöcker … What would you say is interesting about Millöcker for the English speaking world, then and now?

The book by Marga Walcher from 2011 is in both German and English. I had never considered publishing the book in English myself. But why not? Millöcker was quite successful in England and the USA during his lifetime. “Millöcker is one of the best, freshest Viennese operetta composers. He has written waltzes that would have traveled the world if the name Strauss were on the title page,” wrote a critic from the Wiener Abendpost on December 7, 1882, about the premiere of Der Bettelstudent. The melodies of Johann Strauss II are still successful worldwide today. If Millöcker were marketed correctly and a well-known singer or conductor were to support him, I would see definite chances of success. Gasparone was performed in New York as early as 1885, and even the little-known work Apajune was staged at the New York Casino Theatre. Der arme Jonathan enjoyed successful premieres in Russia, the USA, and in 1891 at the Opera House in Melbourne. Der Vize-Admiral was successful in New York as The Black Hussar.

Alexander Girardi as Jonathan Tripp in Millöcker’s “Der arme Jonathan” at Theater an der Wien. (Photo: Rudolf Krziwanek / Theatermuseum Wien)

Thus, an English-language book would certainly have been of interest earlier. Today, I would rather doubt that, as the interest in operettas is unfortunately quite low, and there is much to discover in the genre of operetta in the USA as well, for example, the works of Victor Herbert, John Philip Sousa, Rudolf Friml, Sigmund Romberg, or even Victor Hollaender, who worked in the USA.

Do you have a favorite Millöcker show/recording?

There is a record with a complete recording of Der Bettelstudent from 1966. The Berlin Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Robert Stolz. Among the singers are Hilde Güden, Fritz Ollendorf, and Rudolf Schock. Why do I cherish this recording so much? It has a very nostalgic reason. My mother often listened to this record during my childhood. Not least due to my grandmother’s stories about how she enthusiastically watched operettas at the theater in Franzensbad in the 1920s, and my mother’s records, my enthusiasm for operettas was awakened.

What was the worst Millöcker performance – on stage or on record or film – that you’ve ever seen?

Unfortunately, Millöcker’s operettas have been seen very little on stage in recent years. Regarding film adaptations, the one by Werner Jacobs from 1956, featuring Gerhard Riedmann, Waltraud Haas, the Kessler twins, and Gustav Knuth as Colonel Ollendorf, was unsuccessful. To quote the Filmdienst No. 3 from 1957, the adaptation is a “farce garnished with some musical remnants [...] lacking in verve, humor, and stirring music [...]. The jokes are drawn from the repertoire of slapstick, played rather casually. The whole thing is poor entertainment, a limp hybrid that does not dare to embrace the musical verve of genuine operettas but also fails to completely detach itself from this model. A banal little game with rather dull disguise jokes and a lot of sudden love.” That sums it up well.

Are there any Millöcker highlights to look forward to in the future, exhibitions, films, documentaries etc.?

The Lehar Festival in Bad Ischl is performing Bettelstudent this summer. The Volksoper Vienna also has the 2022 production of Die Dubarry (in Theo Mackeben’s version) with Annette Dasch and Harald Schmidt back on its schedule. Even Der arme Jonathan was performed in 2024 at the Schleswig-Holstein State Theater in Flensburg.

Scene from “Der Bettelstudent” at the Lehár Festival in Bad Ischl, 2024. (Photo: www.fotohofer.at)

Millöcker’s estate has been housed in the Vienna City Library since 1961. An exhibition there would be a great idea, as well as in Baden near Vienna, where Millöcker spent many summers before moving there entirely in his final year, and where he died on December 31, 1899. The local city museum contains many original scores. Unfortunately, in Baden, no works by Millöcker are being performed in the 2023/24 or 2024/25 season. I do not believe there will be any films or documentaries. However, it would be nice if, for example, the Vienna Philharmonic would include a work by Millöcker in their New Year’s Concert program, as this would enhance his recognition and be a fitting tribute for the 125th anniversary of his death

The caption of second illustration in this article tells us that Millocker is to the left and Steiner is on the right. In fact, Millocker is not in the drawing at all. That’s Theater Director Steiner to the left and Alexander Girardi on the right.

On quite another matter, my introduction to Millocker was a trip to Chicago (I grew up in a suburb) to see the 1956 film on Millocker that is mentioned in this article. I was not impressed, and it’s nice to see that long-ago recollection is confirmed here. However, I continue to feel that Millocker is a distant third to von Suppe, who in turn is a distant second to Johann Strauss II.