Michael Hardern

Operetta Research Center

21 March, 2023

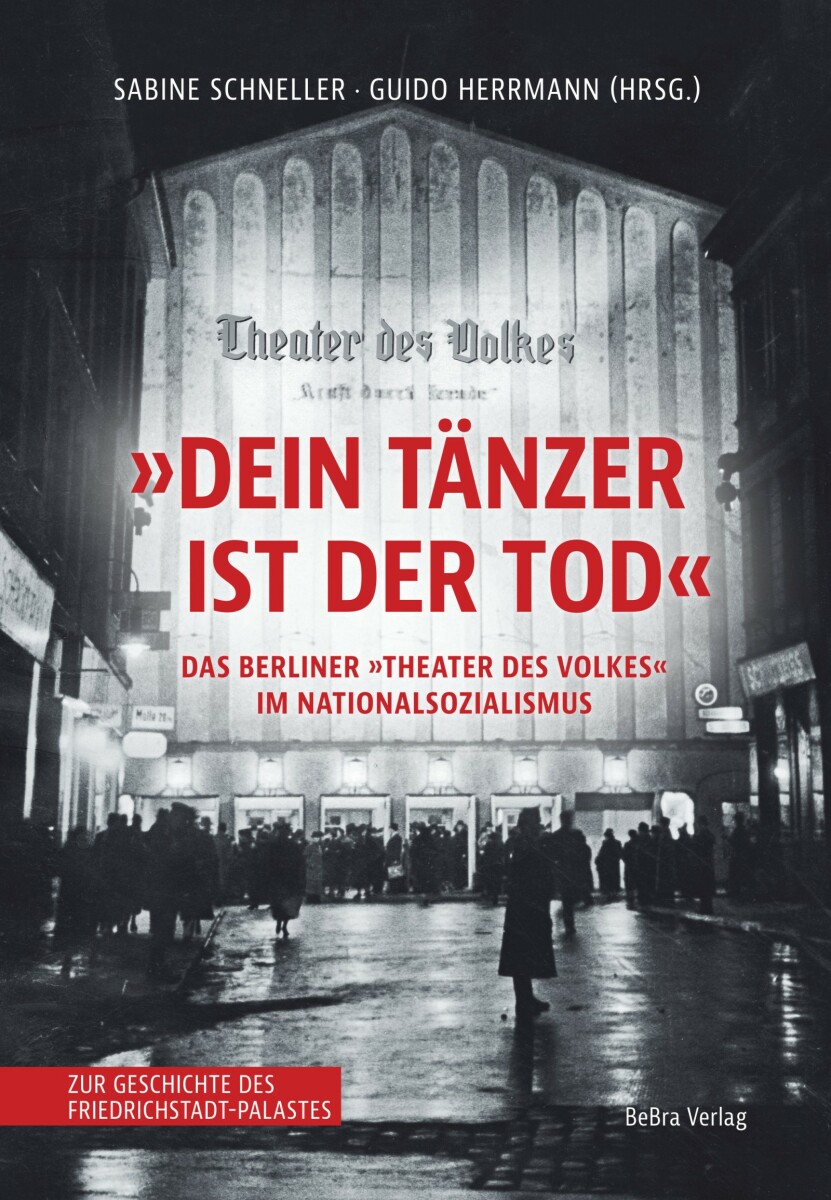

The history of Berliner Großes Schauspielhaus – birthplace of the great 1920s Eric Charell revues and especially of Im weißen Rössl in 1930 – has recently been told many times over. But what happened to this XXL venue after Charell left for Hollywood and the Nazis took over in 1933? The new publication “Dein Tänzer ist der Tod”: Das Berliner “Theater des Volkes“ im Nationalsozialismus tells that story for the first time, in detail and richly illustrated.

The cover of “Dein Tänzer ist der Tod: Das Berliner ‘Theater des Volkes’ im Nationalsozialismus”, edited by Sabine Schneller and Guido Herrmann. (Photo: BeBra Verlag)

Originally, it was a market hall in the center of town. Then it became a circus, and then Max Reinhardt bought the venue and had it transformed into a theater by the architect Hans Poelzig, who created the famous “grotto” ambience. Reinhardt later installed Charell as artistic director of his theater which became world-renowned as Berlin’s biggest and most modern revue venue – later the place for revue operettas, including the famous trilogy of “history” operettas Casanova, Die drei Musketieren, and Im weißen Rössl.

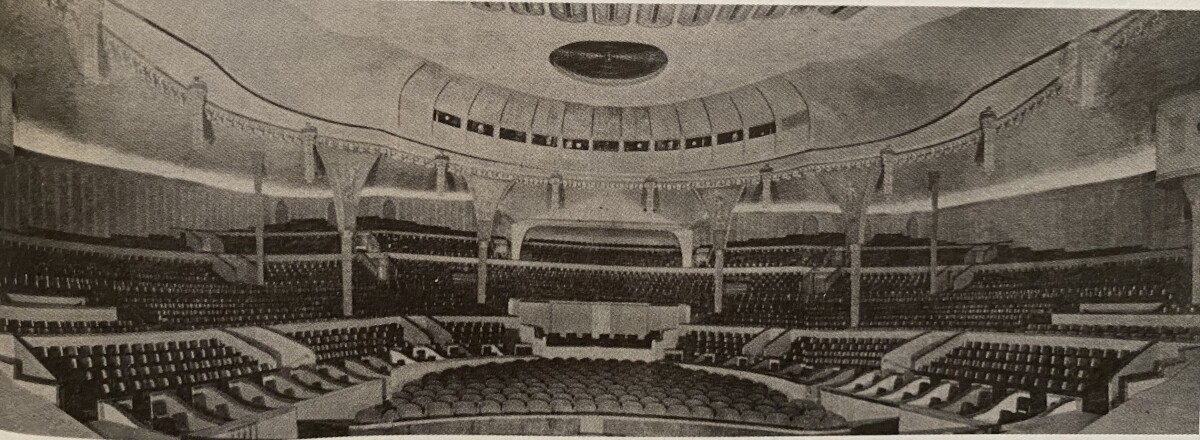

Once the Nazis were in charge, the former private commercial venue became a state subsidized theater under political control, renamed “Theater des Volkes”, i.e. the “Theater of the People”. The Poelzig architecture was destroyed and substituted by something less obviously “modern”. And the 3.500 seats were now filled by workers organizations (“Deutsche Arbeitsfront” and “Kraft durch Freude”), later soldiers were given tickets as well to fill the massive place (there were not as many tourists around anymore as in the days of Charell).

The new interior of the Theater des Volkes in Nazi times. (Photo from: “Dein Tänzer ist der Tod: Das Berliner ‘Theater des Volkes’ im Nationalsozialismus” / BeBra Verlag)

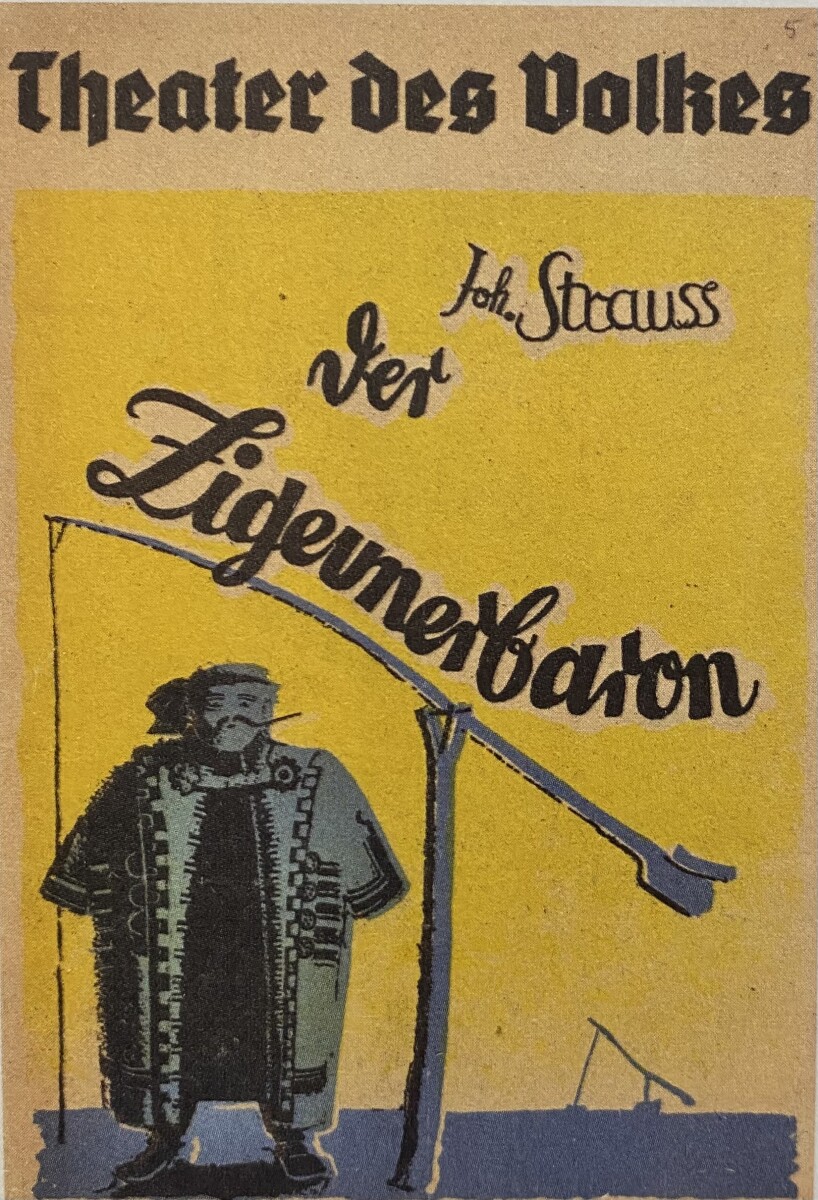

But what did they get to see? That’s what Sabine Schneller and Guido Herrmann chronicle in their new book. Of course, operettas were presented to fit the Nazi definition of “Aryan” entertainment, so you get a lot of 19th century operettas by composers such as Carl Millöcker (Bettelstudent), Franz von Suppé (Boccaccio et al), Carl Zeller (Der Vogelhändler and Der Obersteiger), or Johann Strauss (a newly arranged Ballnacht in Florenz or the more “traditional” Zigeunerbaron).

“Der Zigeunerbaron” at Theater des Volkes. (Photo from: “Dein Tänzer ist der Tod: Das Berliner ‘Theater des Volkes’ im Nationalsozialismus” / BeBra Verlag)

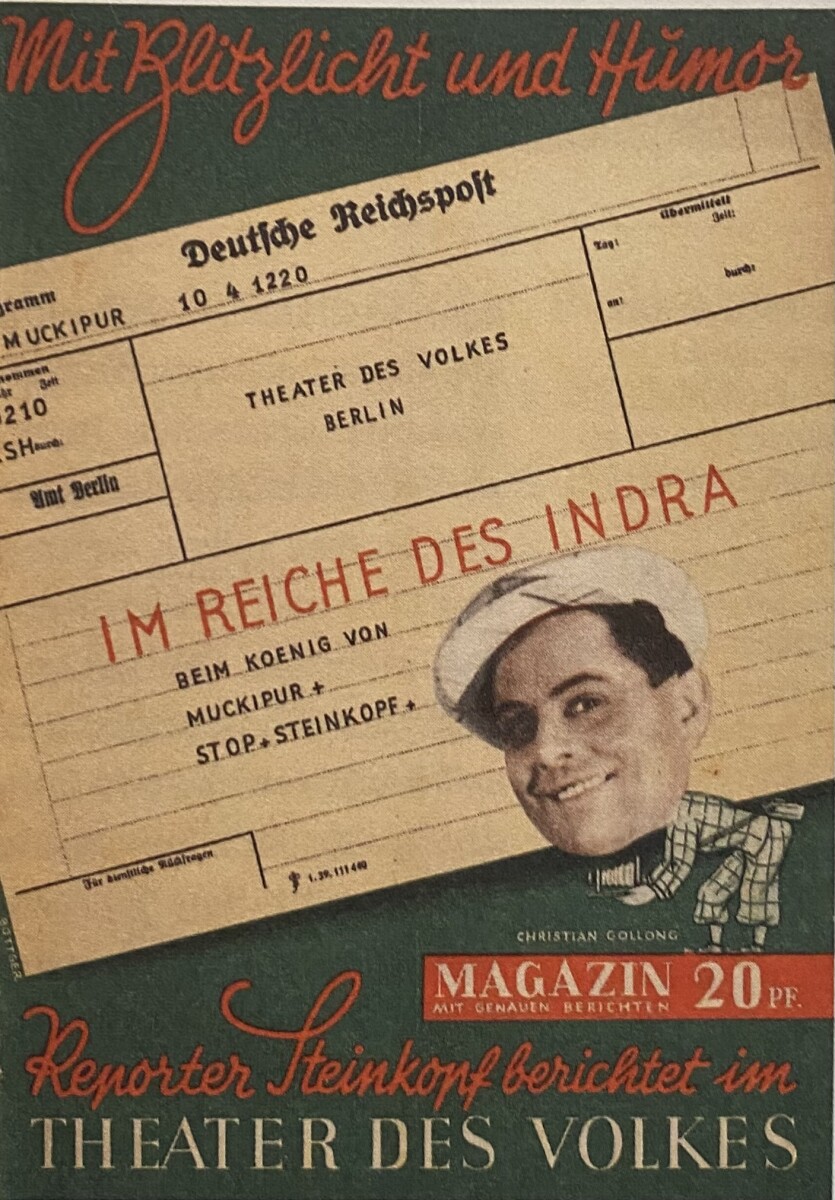

Obviously, works by Hitler’s favorite composer Franz Lehár were presented as well. His Zigeneunerliebe was given with Ingeborg Dörlein and Hans-Heinz Bollmann. The resurrected Paul Linke was honored with a lavish Frau Luna production for this 75th birthday. Also, his older Im Reich der Indra was re-worked and presented in a new version, starring Christian Gollong as a pretty obvious Max Hansen substitute. Equally reworked were the works of Walter Kollo, whose Wie einst im Mai resurfaced, this time without Charell’s jazz additions.

“Im Reiche der Indra” at Theater des Volkes. (Photo from: “Dein Tänzer ist der Tod: Das Berliner ‘Theater des Volkes’ im Nationalsozialismus” / BeBra Verlag)

And for the rest, there were a lot of new works by second rate composers who got a chance to shine, with titles such as Eine entzückende Frau, Saison in Salzburg, Hochzeit in Samarkand or Hofball in Schönbrunn. To name only a few.

Hans Konorek and Irmgard Kern in “Hochzeit in Samarkand”. (Photo from: “Dein Tänzer ist der Tod: Das Berliner ‘Theater des Volkes’ im Nationalsozialismus” / BeBra Verlag)

All these shows are shown in the new book with program booklets, posters or photos of individual scenes from stagings. And it’s amazing to look at these images and realize the drastic change in operetta performance practise pre and after 1933.

In September 1944 all theaters in Germany were forced to close because of the war. The Theater des Volkes was hit by a bomb and severly damaged.

Christian Gollong and Eva Charslotte Hoegel in “Zigeunerliebe”. (Photo from: “Dein Tänzer ist der Tod: Das Berliner ‘Theater des Volkes’ im Nationalsozialismus” / BeBra Verlag)

After WW2 a woman called Marion Spadoni was installed by the Soviets as director of the theater. She rechristens the venue “Palast” (= palace) and marketed it as a “Varieté der 3000”. It was used – in a patchily rebuild form – for concerts in the DDR, until in 1984 the East-Berlin government opened a new theater a mere 174 meters down the road that they called “Friedrichstadt Palast”. It was intended as an updated and ultra-modern version of the former Großes Schauspielhaus, once more specialized in big revues celebrating the superior glory of big city entertainment in socialism.

Now, more than 30 years after the end of the DDR, the present-day director of the Friedrichstadt Palast, Berndt Schmidt, officially apologizes for what happened at his “house” during Nazi times, but also for the many decades when that history 1933-44 has been consciously ignored by historians. He emphasizes that it’s important to also address the dark side of history and be aware of what happened and how, in order to prevent it from happening again.

The entrance to the “new” Theater des Volkes. (Photo from: “Dein Tänzer ist der Tod: Das Berliner ‘Theater des Volkes’ im Nationalsozialismus” / BeBra Verlag)

“Dein Tänzer ist der Tod”: Das Berliner “Theater des Volkes“ im Nationalsozialismus is a book published as part of the series “Zur Geschichte des Friedrichstadt-Palastes“ by BeBra Verlag. It is almost 300 pages of operetta history that has been overlooked by many for so many years.

Even if you don’t read German, you will want to get this publication for the fantastic illustrations alone.

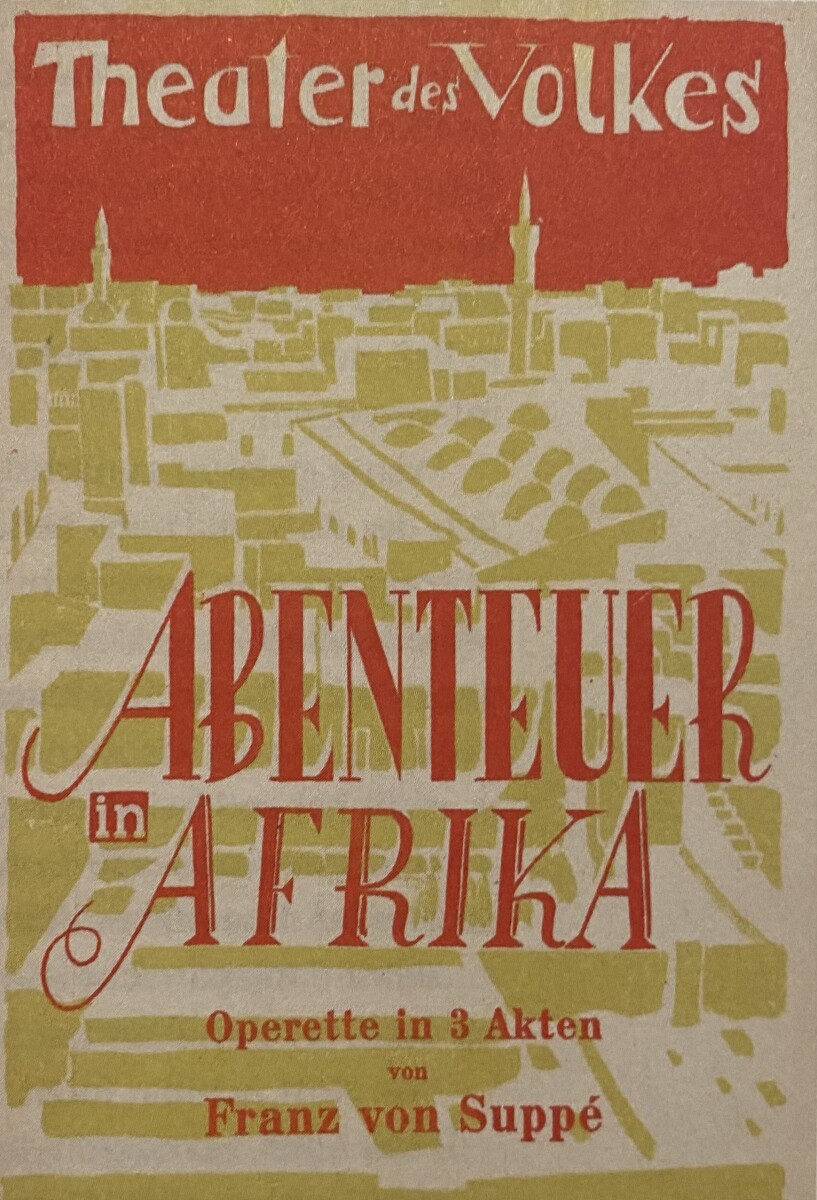

Suppé’s re-written “Afrikareise” at Theater des Volkes. (Photo from: “Dein Tänzer ist der Tod: Das Berliner ‘Theater des Volkes’ im Nationalsozialismus” / BeBra Verlag)

For more information and details about the publisher, click here.

A newspaper photo dated 21/11/1933 in “the General-Anzieger für das Gesamte Rheinisch-Westfälische Industriegebeit” shows the great actor Heinrich George with his arm around the boy who played the title role in the Nazi propaganda film HITLERJUNGE QUEX (Jürgen Ohlsen) with the photo caption reading (trans.):

As part of the founding celebration of the Theatre of 5000, Heinrich George held a dialogue with the Hitler Youth Quex, written by Rolf Brandt.

The film was at the time of this newspaper photo being screened across the Reich in hundreds of movie theaters.